Chotsa chipewa! Choka!

Take off your hat to me! Now scram!

Say you’ve never heard of John Chilembwe,

or of his mission church at Mbombwe

HQ for his First War Rising

first salvo for the Malawi nation.

Yet as surely as my mother lived

on the tracer-path planet

left behind in our world’s world line

so surely my memory discovers her

not in chemical coding but alive there still

and so surely John Chilembwe still gives off

that black light in his black preacher’s suit

or is alive in all our pasts before our birth

not in the photos recovered when they shot him down

but still running from the troops

towards Moçambique unarmed, hot-fleshed,

in dark blue coat, striped pyjama jacket

coloured shirt, grey flannel trousers

running for about a mile before

Mlanje Police Private Naluso shot him;

the bullet spun him around and around,

Sergeant Useni hit him again,

I hit him through the head,

said Garnet Kaduya, Church of Scotland,

in a language truly dead, but Chilembwe was

spinning

as they pulled and snapped the life-thread

in that present moment.

He’s still alive as he turns

just a second before the shooting;

and so I may tell you his story,

not tapping into memory but into time,

and refire the first salvo for the end

of white hegemony in Central Africa.

You must come along. Whether you’re a

Caribbean in Brixton able to instruct me,

or white middle class in Surrey,

or an elderly person on welfare in Consett,

or a blurty-eyed young person,

whether you ever read poetry or not,

all our paradoxes meet in Chilembwe’s life.

Let me take you into the stolen land

by the huge lake, and I’ll come to meet you

as some District Commissioner

my tie round its stiff collar

like a ribbon round a white plastic pot

from your own days. I’m still alive

in arm-creased jacket parted

over tweaked waistcoat,

topi going grey, white ducks

flattened on my shins. You

come back to me with old books:

I come towards you with your modern

news cuttings: racial attacks in England

and Wales doubled in five years,

firebombings, knife attacks, killings.

‘Many black Britons

might eagerly return to their countries.’

And we meet on a bush track

marked with stone spikes.

I doff my hat to the future

as the natives doff their hats to me

even at a thousand yards’ distance.

The Shire Highlands are ours by treaty

stolen from Nyasa tribes illiterate

in our law: price, a gun,

some calico, two red caps, other things,

at one-tenth of a penny per acre

plus road-making, mining rights.

Doubled hut taxes make them work

on white farms, like the harsh Bruce estate

run by Livingstone’s descendants;

planters whip them for misdemeanours,

their goats and chickens grabbed,

no pay, or money thrown on the ground.

Sheer need drives them

to recruit in our German war,

the Boche attacking by lake and land

from the North, long lines of porters

carrying munitions on their heads,

dying in a two-thirds majority

over the whites, their only democracy.

It’s unjust, but they’re not ready for any other.

As Miss Marguerite Roby said in her recent book:

‘It is conceivable that the coloured man in Central Africa

would be happier if left entirely to himself;

but the march of progress is not to be arrested

and when the conquering white enters a black country

labour he must and will have,

let the theorists rave as they will.’

Chiradzulu, you say from your future.

Is this the site of the rising? Where was the church?

You’re talking of John Chilembwe.

I know John, mission educated,

secretive Baptist type in dark suits,

complains we’ve led his people

to war against the Germans.

He’s probably infected with Ethiopianism,

a dangerous millenarian creed.

Who knows what he preaches in that church of his?

Africa for the Africans, I suppose.

Ethiopianism? you say from your future,

I thought that was Marcus Garvey,

rephrased by the Rastafarians.

Marcus who? I’m quoting the 68th psalm,

‘Ethiopia shall soon stretch out her hands to God.’

You see the brick-built church

rising before us over Mbombwe, roofs

frosted with photographic light? Its towers

make it a unit of measurement

fit for your Bromley road but here lost

in the Nyasaland bush.

They’ve laid in the mortar crudely,

harsh lines stripe the entrance steps,

and like a double-exposure the broad white hat

of its pastor, his furiously serious face, drab suit,

almost appear for us in the archway.

That’s John Chilembwe:

he seems to absorb all the light.

But, you say from your future,

he was shot on a hillside

after his followers had removed the head

from William Jervis Livingstone

the Bruce estate manager

and stuck it up in this very church.

Your future events rush towards me in a herd.

The missionaries began the trouble,

Watchtower people,

Seventh Day Adventists,

Seventh Day Baptists, one called Booth

took Chilembwe on as a servant,

sent him to America to mix

with the radicals there.

John came back as a qualified reverend

to set up African-run missions

with American Negro support.

Had the effrontery to build this huge church

and prayer houses across the Bruce estate,

which Livingstone had to burn

or the natives would think they had land rights.

But all was manageable until the war.

Here is part of a letter

we censored from the Nyasaland Times

under emergency regulations.

THE VOICE OF AFRICAN NATIVES IN THE PRESENT WAR

We understand that we have been invited to shed our innocent blood in this world’s war which is now in progress throughout the wide world ...

A number of our people have already shed their blood, while some are crippled for life. And an open declaration has been issued. A number of Police are marching in various villages persuading well built natives to join in the war. The masses of our people are ready to put on uniforms ignorant of what they have to face or why they have to face it ...

Because we are imposed upon more than any other nationality under the sun. Any true gentleman who will read this without the eye of prejudice will agree and recognise the fact that the natives have been loyal since the commencement of this Government, and that in all departments of Nyasaland their welfare has been incomplete without us. And no time have we been ever known to betray any trust, national or otherwise, confided to us. Everybody knows that the natives have been loyal to all Nyasaland interest and Nyasaland institutions. For our part we have never allowed the Nyasaland flag to touch the ground, while honour and credit have often gone to others. We have unreservedly stepped to the firing line in every conflict and played a patriot’s part with the Spirit of true gallantry. But in time of peace the Government failed to help the underdog. In time of peace everything for Europeans only. And instead of honour we suffer humiliation with names contemptible. But in time of war it has been found that we are needed to shed our blood in equality. It is true that we have no voice in this Government. It is even true that there is a spot of our blood in the cross of the Nyasaland Government ...

JOHN CHILEMBWE

In behalf of his countrymen.

Your future rushing ... tells me

that this man is more dangerous

than we’d thought. Time is flickering ...

Something’s happening here ...

as we stand on this bush path together ...

how has the time passed by ...?

Well, I have been badly shocked by recent events.

Shall I tell you how his so-called battalions,

no more than two hundred natives,

killed Mr Livingstone a few weeks ago?

It’s an exciting story:

The whites were making merry

at the Blantyre Sports Club.

The natives with their spears and an axe

went creeping across the Bruce estate in the night,

haunting the Livingstone house.

Mrs MacDonald, undressed,

opened a bathroom window,

saw shadowy Africans holding sticks.

Thought the sticks were firewood, d’you see.

Livingstone himself was letting a cat out

when five or six natives broke in with spears,

and he fought them with rifle butt

from room to room until they stabbed him.

Mrs Livingstone told me:

‘He did not appear to be dead.

He fell on his side.

I tried to turn him over on his back but did not succeed.

I looked for a bottle of Port wine.

The bottle was snatched out of my hand by a native

and just then another ... came in with an axe

and proceeded to cut off my husband’s head ...

in my presence.’

Two other Europeans were murdered and –

I’ve heard enough, you say from your future,

of the deaths of three whites

in one murderous gesture I may not condone.

You forget the Africans sagging into the dust,

their whole continent now unremembered by Britons

who still profit from Western hegemony,

whose shiny liberal shoes walk over these memories.

But where was Chilembwe?

Back in his church, waiting for the head,

or upon Chilimangwanje Hill,

praying on his Mount of Olives,

He intended martyrdom, not victory:

‘Strike one blow and then we die.’

We chased him across another hillside,

his Calvary,

recovered a pair of gold spectacles

and a pair of pince-nez, the right lens

missing in each case,

found next to his half-starved body.

Then we obliterated his memory

and dynamited his church. If you look again

across the bush you’ll see

the great church first bowed to its knees

like a shot giraffe, then the roof

sagging in like tarmac in an earthquake.

And we have imprisoned those Adventist missionaries

beside the African traitors

because the white fanatics set the fuse

and won’t be executed for it.

D’ you know what they say?

‘Six more of our teachers have been taken prisoner.

The flogging of prisoners goes on just the same.

I do think they might have some consideration for us

and punish them outside the place. A European

ought not to be allowed to stay in a place like this.

Sunday of all days is the worst.’

Is this, you say from your future, why

oligarchal Malawi banned

Watchtower Witnesses with their wild

and democratic armageddons?

Where’s Malawi? ...

The question returns me

to a modern time of writing.

In my mind this past survives

as this more-than-memory.

Not even Chilembwe’s religious myths

pass away, though in my own beliefs

no man was resurrected

after any Calvary except in the strange survivals

of all this time as a haunting

of our sadly avaricious, racist British lives,

survivals as shadows outside a cosy house,

where we sit eating goats and chickens

grabbed from Africa via foreign loans,

money thrown on the ground.

Chilembwe said:

I am afraid of the war, which exists between Great Britain and Germany, war the results of which are world wide, and which has already paralysed all business in Africa. I don’t know how you can help us, but by all means try to send us something to sustain our lives and bodies, for we, as well as those who are taking part, are greatly in need. Please in some way send us help, or leave us to die if you choose. At this writing I am penniless. Pray that God in his Chariot may bring messengers of peace and that the Nations may be brought back to the Temple of Peace.

And we imagine the First World War is over!

‘... kindhearted Chilembwe,

who wept with and for the writer’s

fever-stricken and apparently dying child,’

wrote the restless Seventh Day man, Joseph Booth.

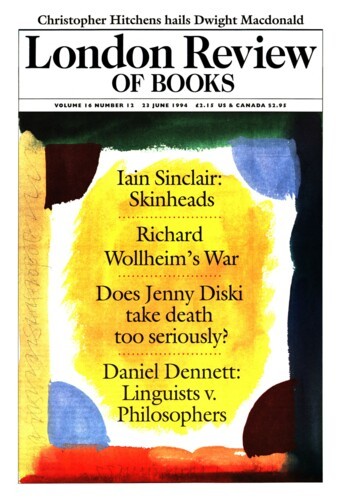

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.