A word to come lies in a little night

where ash is falling.

The word can’t be this ‘coffin’,

lying in its candour, in its cinders.

Inside, the poet’s too lazy in his death

to perform a truth singly. All’s ambiguous.

Yet a coffin is blocked in boldly, I see,

under the washing down of night.

The cobalt blue cabinet’s cut on a slant

with candelabra making mirrors

along its sides peopling it with mourners,

delegates from the governments of poetry

and from their industries, who appear

only as reflections of shoulders.

Hostility of moths round the candles.

Hostility of mouths still saying ‘coffin’.

The coffin waits in this little night

for the whole day’s train.

My own face, visible in the mirrors now,

is a bruise again floating in hints of crystal.

I don’t yearn towards my shadow, bowing

to it, reaching out to find lost unity;

for if the shadow really touched my finger

untruth would constitute truth, whereas

as Buber knew, the process takes a Thou.

Our shadows lack performance;

they are a text created by the dusty mirror:

I do all the touching and my finger

returns with its ashen tip, as you

the reader, when you touch these unreal ashes,

find your own fingertip is clean.

In our candour to be truthful, we’re very stern

and talk too much of loss, covering our truths

with ashes – like authoritarian fathers

who damn their sons with an over-strict word:

‘You’ ll never amount to anything.’

The word I care about

(it’s been lying inside the slant cabinet)

wakes and now performs itself.

The word becomes ‘Celan’, formerly ‘Antschel’:

the only poet I have to struggle against

because none wrote more beautifully post-war

of the perfection and terror of crystal.

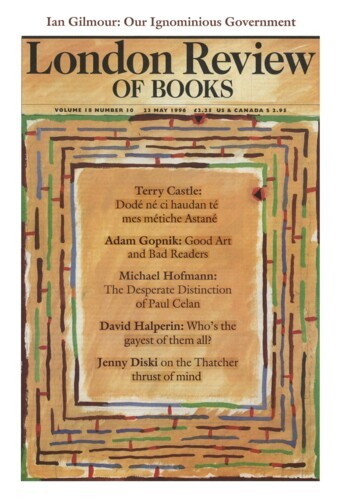

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.