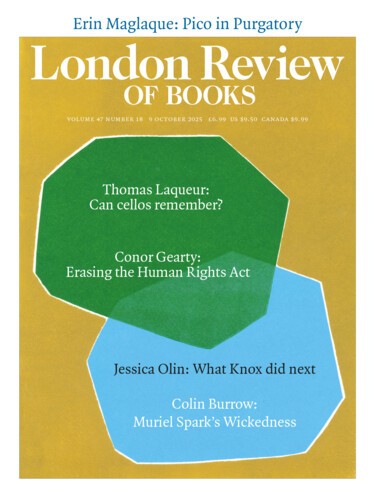

In January , the editors of the London Review forwarded a request to me from Hermione Lee. She was hoping to use a photograph of Anita Brookner that had appeared on the cover of the LRB in 1982 as an illustration in her forthcoming biography of Brookner. The picture had been taken by my father, Peter Campbell, and I knew that the original, if it still existed, would be among thousands of other 35 mm black and white negatives, trimmed to six shots per strip, some of them in labelled envelopes but most forming a forbidding coil in a shoebox that had remained untouched since Peter’s death in 2011. I agreed to try to find the picture and decided to combine it with a chore I’d been putting off.

Photographic negatives are fragile, prone to scratching, fading and decay, and many of Peter’s are well over sixty years old. Rather than peer at them strip by strip, hoping to happen on a particular image, over many weekends I made digital versions of all of them. Scanning each negative to a resolution plausible for reproduction takes about a minute and it turned out that there were about eleven thousand of them. Hermione was pleased when Anita Brookner turned up at around the three thousand mark, but I was left wondering whether anyone but Peter’s family and friends would bother to look at the others. In the hope that they would reach a slightly wider audience, I posted a dozen or so pictures online and sent a link to Café Royal Books, an independent, family-run publisher of photo books based near Southport. A couple of months later, Craig Atkinson, the firm’s founder, wrote to me asking to see more. I sent him a digital archive of around two thousand pictures and, with an alacrity that would astonish anyone who has worked in publishing, three weeks later he mailed me a parcel of finished copies.

The speedy turnaround is made possible by an economical and efficient publishing model. The books are edited and laid out by Atkinson, each a selection of photographs, almost always by a single photographer, the title usually being where and when the pictures were taken (Peter’s is London, 1960-63). They are printed by a local firm and produced to a standard format: slightly smaller than A5, on paper heavy enough that ghosts of images don’t haunt the other side of the leaves. They typically run to 36 staple-bound pages, with little or no text beyond the title and colophon copy on the cover. Contractual terms are straightforward: no payment, but of 250 copies photographers get a tithe of 50 to do with as they wish, and Café Royal takes the rest to sell online, either as individual copies or to their monthly and annual subscribers. They cost £6.70, so as to be about ‘the price of a pint’.

But do 36 pages really constitute a book? One answer can be found on the homepage of Café Royal’s website. After praise from several photographers, curators and collectors comes a comment from a (former) customer: ‘I have never been so disappointed in a book. In fact, these definitely aren’t books.’ Atkinson himself is not unequivocal. In The Book Makers (2024), Adam Smyth asks him: are they books? ‘I don’t know,’ Atkinson replies. ‘Books, zines, pamphlets … “Information pamphlets.” I quite like calling them that. But, you know, who’s going to buy an “information pamphlet”?’

A formal definition of the works as individual publications is rather beside the point. Café Royal has been publishing one a week since 2012 and the number of titles has passed seven hundred; together they constitute a singular record of British and Irish vernacular photography between about 1960 and 2010. Although the books are collected by, among other institutions, the Tate, MoMA and the V&A, Atkinson’s ethos is cheeringly democratic. He sometimes approaches photographers whose work he knows (he has published selections from Elaine Constantine, Chris Killip, Martin Parr, Homer Sykes and others), but most of the books begin with unsolicited submissions from amateur or professional photographers, or heirs to neglected shoeboxes.

The snapshots in Peter’s book were taken during his first three years in London, after he emigrated from New Zealand with my mother. The picture shown here was taken at a Stepney street market. I wonder whether this was one of the photographs he had in mind when, some years later, in a review for the Listener, he wrote: ‘When a glum, derisive, sulky or tired face looks out at you, remember it is the photographer he is seeing – not you.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.