Comic strips and comic books are quintessential creations of America’s 20th-century culture industry. They are also perhaps its lowliest products. Yet this trash medium, with its presumed audience of subliterates and kids, has produced its own geniuses, not all of whom were Disney prodigies of brand creation and marketing. Chester Gould, the hard-boiled newsman responsible for the harsh dynamism of the long-running detective strip Dick Tracy, is one. George Herriman, inventor of the sweet, enigmatic Krazy Kat, a strip that refined a single situation for more than thirty years, is another. And then there is Robert Crumb, better known as R. Crumb, the originator of so-called ‘underground comix’.

Now 82, Crumb is America’s greatest cartoonist. Inimitable and inventive as Herriman and Gould were, neither had his range, nor his independence. Crumb, who developed a rounded, cuddly style reminiscent of Depression-era cartoons, is also a great draughtsman, with a capacity to render fastidiously detailed naturalistic drawings. Technique alone cannot account for his eminence, however. Crumb is both an observant satirist and a self-aware student of his own drives. His grasp of American vernacular and his sardonic humour suggest a comparison with Mark Twain as well as with Twain’s admirer, the proudly prejudiced social critic H.L. Mencken. Rambunctious and often offensive, Crumb draws freely on pre-existing racial and gender stereotypes, and always draws in the first person – typically representing himself as a scrawny, misanthropic loner, obsessed with sexually dominating (or being dominated by) Amazonian women. Unlike any previous comic-strip artist (but not unlike a stand-up comedian), Crumb is his own flawed persona. ‘The Many Faces of R. Crumb’, a two-page spread produced at the height of his powers in 1972, begins with a ridiculous image of the artist masturbating to one of his own comics and ejaculating out of his studio window, then goes on to depict him as a penitent saint, a fascist creep, a self-centred SOB, a sentimental slob, a rugged individualist and a guilt-ridden crybaby.

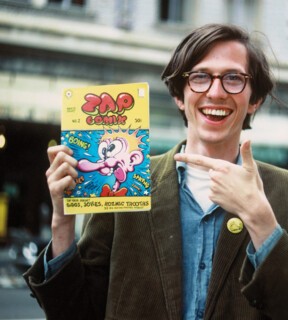

Before Crumb, no artist had so openly used comics as a means of personal expression. After Crumb, the deluge, starting with the underground cartoonists who followed in the wake of his Zap Comix (1968), a 24-page pamphlet that – according to one of his drawings – Crumb and his first wife, Dana Morgan, sold for a quarter out of a baby buggy on the streets of Haight-Ashbury. The cover was designed to shock, depicting a self-electrocuting naked man, plugged into a light socket and launched into the air in a foetal position. Addressing itself to ‘flipped out flower kids’, Zap proselytised for marijuana and introduced Crumb’s irascible Old Testament guru, Mr Natural. News stands and bookshops were afraid to carry it, but subsequent issues soon appeared in head shops across America.

As both product and co-creator of the 1960s counterculture, Crumb ranks with his less scurrilous contemporary Bob Dylan. But he was less tied to the 1960s than Dylan. He disliked rock music, preferring the rural blues and string-band music of what Greil Marcus called ‘the old weird America’, and poked fun at hippies.* Crumb was famous but not as famous as he might have been (or as rich). For most of his career, he received equal parts criticism and acclaim. To get Crumb, as the art director Françoise Mouly wrote (in appreciation), one had to reckon with his ‘occasionally repulsive depictions of women, blacks and Jews, and his endless graphic representations of kinky, smelly, sweaty sex’. Twenty-five years after Zap, he was still best known for his early creation Fritz the Cat (the basis for an X-rated cartoon film by Ralph Bakshi, which Crumb loathed), his jacket illustration for the LP that launched the band Big Brother and the Holding Company and its lead singer, Janis Joplin, and the endlessly pirated cartoon ‘Keep on Truckin’’, which inspired the signature song of another San Francisco band, the Grateful Dead, and, thanks to an industrious lawyer, provided Crumb with a modest annuity.

In the mid-1990s, long after the counterculture had faded, a middle-aged Crumb was introduced to a larger audience by Terry Zwigoff’s documentary portrait of the artist as professional misfit. Crumb (1994) presented its subject as a curiosity, neither hipster nor punk. If anything, with his Coke-bottle glasses, buck teeth, bow tie and stingy-brimmed fedora, he seemed freakishly straight – an American type not unlike William Burroughs or David Lynch. The film featured interviews with his older brother, Charles (who had killed himself by the time it was released), and his younger brother, Maxon. It also included Robert Hughes’s pronouncement that Crumb was a latter-day Bruegel. Crumb, who relocated from rural Northern California to the village of Sauve in the South of France in 1991, has since been incorporated into the art world, largely on his own terms. He was given a major retrospective at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris in 2012 and is represented by the mega-gallery David Zwirner. His napkin doodles, like Picasso’s, may be worth thousands.

Dan Nadel researched his comprehensive biography with Crumb’s ‘permission and support’, and full access to his archives. His account of the Crumb family is fascinating. The middle child of five, Robert grew up in a volatile household. His father, Charles, was an oppressive, straight-arrow Marine Corps officer who later wrote the manual Training People Effectively; his mother, Beatrice Hall, was rowdier, a housewife turned amphetamine addict. The parents fought but stayed together; the family was as close-knit as it was dysfunctional. After numerous moves back and forth across the country, they finally settled in working-class Philadelphia.

The original comic-book nut in the family wasn’t Robert but Charles Jr, who, though he never got beyond pencil and crayon, infected his siblings with his mania. Comic-book lovers of Crumb’s generation are often nostalgic for the EC horror comics – sensational Cold War artefacts driven out of existence by a combination of parental outrage, a Congressional investigation and the bestselling exposé Seduction of the Innocent, written by the psychiatrist Fredric Wertham. Others were deeply involved with Batman, Captain America and the mythological superheroes who have dominated Hollywood productions in recent years. Not the Crumbs. As Nadel writes, ‘the Crumb brothers resented brutish do-gooders solving problems with fisticuffs. Superman was hardly an idol to them – he was more like their drunk uncles and local bullies.’

Charles and Robert took refuge in the child-friendly, character-driven comic books put out by the Dell company: Walt Kelly’s satiric Pogo, the proto-feminist Little Lulu and, most successfully, Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories, which often featured the feckless striver Donald Duck and his unimaginably wealthy uncle Scrooge McDuck. These comics were originally written and drawn anonymously by Carl Barks: the Crumb brothers studied Barks and hand-copied his stories.

Like a mid-20th-century version of the Brontë siblings, Charles, Robert, Maxon and Carol, their older sister, were all busy making ‘funny animal’ comics. As teenagers, Charles and Robert graduated to individual monthly comic books and also discovered Mad magazine, a primer in dissidence and caustic irony which, as Marshall McLuhan once observed, inspired a generation of young beatniks. Robert, unlike Charles, was able, after several attempts, to turn professional. He secured a job at a greeting-card company in Cleveland and, having escaped the family home if not his own nerdiness, found a scene, described well by Nadel, among Cleveland’s dropouts, druggies and coffee-house poets. An artist friend, who ‘knew the bodies Robert liked’, introduced him to Dana Morgan, the ‘zaftig moon-eyed girl of his dreams’, as Nadel puts it. He was 21; she was 18. They married a few months later.

Always industrious, Crumb made contact with one of his idols, Mad’s founder, Harvey Kurtzman, and contributed work to Kurtzman’s short-lived satirical publication Help! Not long afterwards, he began sending cartoons to underground newspapers, notably New York’s East Village Other. In addition to his retro style, Crumb developed a fully-fledged anti-establishment sensibility – based on sex, drugs and a contempt for ‘official’ America. He had experimented with LSD before arriving in San Francisco; once he was there it became habit. The drug encouraged free association and disinhibition. Crumb dredged up and declined to censor his deepest sexual and racial fantasies. His confessional, transgressive comics, featuring such characters as Mr Natural, Whiteman, the Desperate Character, the Ruff Tuff Creampuff, Angelfood McSpade and the Snoid, both addressed and satirised his generation. (LSD may have liberated Crumb, but it apparently had no effect on his sartorial sense. In Haight-Ashbury, most people thought he was a narc even as he was becoming a local celebrity on a par with San Francisco’s psychedelic bands.)

In addition to Zap, which became a vehicle for fellow underground cartoonists and survived several censorship battles, Crumb continued to put out solo comics. Between early 1969 and late 1972, he published twelve of them, beginning with two issues of his mock New Left Motor City Comics, devoted largely to the adventures of Lenore Goldberg and her Girl Commandos. These were followed by the aptly named Despair (the cover showed a lower-middle-class couple too paralysed even to turn on the TV); the more light-hearted Uneeda (detailing a teenage runaway’s picaresque sex education); two issues of Mr Natural; Home Grown Funnies (in which the uptight White Man is kidnapped by and falls in love with a female Bigfoot); the even more absurdly kinky Big Ass Comics; Your Hytone Comix, which features an anthropomorphic toilet; and the classic XYZ Comics (including, among other things, ‘The Many Faces of R. Crumb’ and an eight-page exercise called ‘Cubist Bebop Comics’). The cycle ended with The People’s Comics, in which Fritz the Cat is felled with an ice pick by an irate girlfriend, Andrea Ostrich. The stories in this sustained run, never to my knowledge republished as a collection, were sharp, inventive and hilarious. Each followed the one before like a succession of hit singles. For a time, Crumb did actually turn from comic books to music, touring with a band, the Cheap Suit Serenaders, playing a repertoire drawn mainly from the string-band music of the 1920s. At the same time, he drew heroic, loving cartoon portraits of bluesmen and country musicians, uncannily reproducing the letter fonts and advertising layouts of the period.

The counterculture collapsed, as did Crumb’s marriage. He moved to rural California and, though polyamorous by inclination, in 1972 fell into a relationship with Aline Kominsky, a fellow cartoonist from suburban Long Island; he married her six years later. If Crumb was the Bruegel of cartooning, Kominsky was the Jean Dubuffet. Indifferent to perspective, her art brut comics were assertively crude in both style and content. For the cover of Twisted Sisters, produced in 1976 in collaboration with Diane Noomin, she drew herself perched on a toilet, face straining as she regards her image in a hand mirror and wonders about the number of calories in a cheese enchilada. In Kominsky, Crumb had met an artist as strong-willed and uninhibited (or narcissistic) as he was. With Aline and Bob’s Dirty Laundry Comics – shocking less for its graphic slapstick account of the couple’s sex life than the contrast between his refined and her artless drawing – the two began an intermittent collaboration that lasted nearly fifty years until Aline’s death in 2022.

In the mid-1970s there was an attempt to revitalise underground comix, first with the magazine Arcade, edited by Bill Griffith and Art Spiegelman, a publication that brought together cartoonists with ageing beat writers such as Burroughs and Charles Bukowski; and then, after Arcade’s demise, with the magazines Raw and Weirdo. The latter, edited by Crumb, was an updated take on Mad magazine, including drawings as well as comic strips. Raw, which Spiegelman edited with his wife, Françoise Mouly, was more open to graphic experimentation and European cartoonists. From 1980 onwards, it also serialised Maus, Spiegelman’s account of his attempt to comprehend his parents, who had survived the Holocaust in Poland.

There are comics before Crumb and comics after Crumb, but there is also Crumb after Maus, a graphic novel which, in its subject matter, emotional power and narrative complexity, made all previous underground comix seem a bit trivial. In 1992, the year after Maus appeared in its completed form, Crumb made his own first tentative contribution to the graphic novel form, accepting a commission to illustrate David Zane Mairowitz’s Kafka for Beginners (1993). Employing the fastidious shading and cross-hatching style with which he portrayed old blues singers, Crumb illustrated The Metamorphosis, The Trial and The Castle as well as key episodes from Kafka’s life. As demonstrated by Orson Welles’s laboured adaptation of The Trial, these novels resist visualisation, and although Crumb’s drawings are technically impeccable, the effect is overly literal and oppressively heavy. (Nevertheless, according to Nadel, Crumb ‘feels it’s some of his best work’.)

In the mid-2000s, Crumb turned from the great Jewish modernist to the ultimate Jewish text, the first book of the Torah. Nadel treats Crumb’s Book of Genesis (2009) as a magnum opus. Perhaps it is. Heavily researched and meticulously drawn, it took Crumb four years to complete, as long as it took Michelangelo to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The original drawings, exhibited at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, were sold to George Lucas in 2019 for $2.9 million and take pride of place in his Museum of Narrative Art. Unlike any previous Crumb publication, The Book of Genesis was respectfully received. The biblical scholar and translator Robert Alter accepted it as a genuine Midrash. Harold Bloom reviewed it in the New York Review of Books in a piece that was largely concerned with a rereading of Thomas Mann’s Joseph tetralogy. Bloom concluded with regrets that he hadn’t been ‘more gracious’ to Crumb, who had returned him to Genesis; but in comparison to Mann, Bloom felt, Crumb hadn’t sufficiently appreciated Yahweh as a literary character.

It’s true that, even more than with Kafka, Crumb seems overawed rather than inspired by the material, deserted by his well-honed sense of the absurd. The Book of Genesis may have elevated the medium, as had Maus, but put alongside Crumb’s earlier work, it feels as ponderous as a stone tablet and scarcely more consequential than a footnote. One can only imagine the cosmic desecration had Crumb reverted to his Bruegelian style and portrayed capricious Yahweh as a version of Mr Natural. The book is dedicated to Kominsky, whose facial features are ubiquitous among the Old Testament women.

Childhood formation can be the most compelling aspect of an artist’s life. Although neither of Crumb’s parents were religious, they regularly attended church. What’s more, they subjected their children to a Catholic education because Charles Crumb, an atheist, felt it would instil a sense of discipline. That it did, albeit with unexpected results. The Book of Genesis is one. Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life, his de facto memoir and true confession, is another.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.