In France , Chris Kraus wrote in an essay from 2003, there exists ‘a formal/ informal structure for the perpetuation of a dead artist’s work’ that gets called ‘the Society of Friends’. The friends gather up the artist’s work, plans, notebooks and so on and write and elicit tributes, then publish the lot in a book called the ‘Cahiers’, maybe at their own expense. ‘Why do the friends do this? It can only be that they believe, in some real way, the friend’s life and work belongs to them … It speaks for them because they shared a place in time.’

She begins her present book, which ‘may or may not be a biography of Kathy Acker’, by evoking the circles that gathered around her subject’s ashes in the weeks after her death from metastatic breast cancer in an alternative medicine clinic in Tijuana in November 1997. Seventeen people arrived at the house of the poet Bob Glück in San Francisco that December for a ceremony with a Nyingma Buddhist practitioner. Most of the group consisted of what Kevin Killian remembers as ‘New Agey-type people who had helped Kathy in her last years. Tattooists, bodybuilders, motorcycle girls, S/M practitioners, herbalists, it was almost like an upstairs-downstairs thing.’

A few weeks after that, a smaller group attended a sea-scattering at Fort Funston, the location picked by Matias Viegener, the friend who had done most to look after the dying Acker and whom she had appointed her executor. Frank Molinaro, whom Acker had paid for astrological advice, passed out business cards in the car park, then grabbed hold of the vase with the cremains in it. ‘The astrologer ran toward the sea tossing handfuls of ash and bone while he proclaimed – “You’re free, Kathy! You’re finally free!”’ ‘Where to inter the remains of those who live in a state of perpetual transience?’ Kraus asks. ‘To remain in one place is either privation or luxury. No one I know who’s died in my lifetime … has been interred in a grave.’

Born in 1947 in New York City, Kathy Acker lived and worked as an adult in lots of places, most significantly downtown Manhattan, San Diego, London and San Francisco, with long spells of gigging and episodes of sudden geographical flight. In her lifetime she published eight or 13 or more novels – it depends how you count them – since supplemented with a substantial Nachlass. For a time, she was ‘the most shoplifted female author in the world’. She bought places to live in Barnes, Islington, Brighton, East 12th Street in Greenwich Village: at one point she was paying for three homes at the same time. ‘Oh sure, we all look glam while travelling,’ she said to a friend, ‘we’re good at media images.’ But as she wrote in her picaresque novel Don Quixote, ‘even a woman who has the soul of a pirate … who is a freak in our society, needs a home.’

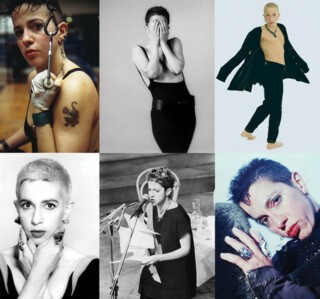

Acker, Kraus thinks, staked her all on a bid to become a ‘Great Writer as Countercultural Hero’, a position no woman had held before her, and I’m not sure any has held since. She died before the internet properly got going, when becoming famous or celebrated or iconic was a completely different matter from what it is now. Photographs were key, and Acker photographed brilliantly, especially in the shots taken by Robert Mapplethorpe: that soft, white face, with big, round eyes in the cheeks of a chubby cherub; that soft, white skin, pierced and pinched and hyperextended with hooks and rings and belts and dumb-bells: Acker was lifting weights long before lifting weights went mainstream, and probably met Mapplethorpe because of the pictures he was taking of the bodybuilder Lisa Lyon, who worked out at Acker’s gym.

Performance was also important. Acker was a charismatic live reader, and followed the example of her hero, William Burroughs, by touring clubs and music venues, building fans among people who didn’t usually buy books. Transgression too was important for such an audience, transgression and a sense of lineage with other transgressors, a secret club for fans to join: ‘She very swiftly became the ambassador to this London post-punk scene of an international idea of what an avant-garde might be,’ Michael Bracewell explained to Kraus. Acker explored the roots of her own subculture, and the roots of those roots too: Burroughs took her to Genet, who took her to the French and anti-French traditions, both homegrown and that of the anti-colonial resistance. Rage, political and personal, took her yet further, to the assassins of 12th-century Persia, the nihilists of 19th-century Russia. I could go on.

In 1984, the South Bank Show broadcast a 45-minute portrait of Acker, in which she reads from her novel Blood and Guts in High School over shots of herself stomping the slushy pavements of the then ungentrified Lower East Side. It’s a remarkable document, easily findable on YouTube. ‘What we want to look at is the hard edge of a tough, fashionable, self-conscious group, now at the top of the New York avant-garde art world,’ Melvyn Bragg explains, blunt brown sideburns toning nicely with his blunt brown tie. A bit later he addresses Acker directly. ‘You talk in your books about doing away with meaning. What do you mean by that, more precisely?’ She smiles.

For this appearance, Acker had her hair bleached and buzz-cut and further divided into roughly razored squares. She’s wearing something black and hairy, with clanking hardware on ears and fingers and a tie like a noose round her neck. Her answers are straightforward, well formed, uncompromising but charming, with something indescribably touching in their delivery, like she’s an angelically earnest, bordering on nerdy, little boy. ‘In fact in this apartment there were 13 murders, I think three or maybe two years ago’ – her eyes could not get any wider or rounder. She smiles, meltingly, looking up something in Great Expectations, her version of the Dickens novel. ‘It’s a wonderful book – the Dickens, I mean.’ She mentions Keats, his letters to his brother. ‘Oh, he’s wonderful, isn’t he?’ Bragg agrees.

And then she performs an extract from Great Expectations, sometimes eyeballing the camera, sometimes sweetly looking down:

The author of the work you are now reading is a scared little shit. She’s frightened, forget what her life’s like, scared out of her wits, she doesn’t believe what she believes so she follows anyone. A dog. She doesn’t know a goddam thing she’s too scared to know what love is she has no idea what money is she runs away from anyone so anything she’s writing is just un-knowledge.

Conveniently, the clip stops just there, before the next bit, which is:

Plus she doesn’t have the guts to entertain an audience. She should put lots of porn in this book cunts dripping big as Empire State buildings in front of your nose and then cowboy violence: nothing makes any sense anyway. And she says I’m an ass cause I want to please.

What’m I going to do? Teach?

In her lifetime and after it, Acker became as well known as a face, a body, as she was as a writer. In London in the 1980s she got into BDSM, and tattoos, and motorbikes, so placing herself in the vanguard of the fashions for public sex and body modification that marked much LGBT militancy in the early years of Aids. For these reasons and many others, she is often remembered as a queer icon. And yes, Acker had a lot of sex with both men and women, but as Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick explained in Tendencies (1993), that’s far from all that queerness is about. More expansively, it names what Sedgwick called ‘the open mesh of possibilities … when the constituent elements of anyone’s gender, of anyone’s sexuality, aren’t made (or can’t be made) to signify monolithically’ – when a woman, maybe, doesn’t signify as a wife or mother or interested in men or in possession of a vagina; though Sedgwick’s examples go a fair bit further than that.

The family, for example, is defined by Sedgwick as ‘an impacted social space in which all the following are meant to line up perfectly with each other’, and she lists 15 attributes, including surname, a sexual dyad, an economic unit, a system of companionship and succour, and notes that, for most people in most familial spaces, they don’t line up. Acker’s certainly didn’t, and the misalignments in her family were extreme, as was her sense of her body, her health, her love life, her subjectivity, and it could be a symptom of all these painful fractures that friends remember her so often as so awful: needy, manipulative, narcissistic, sleeping with everybody’s husband, leaving all the dirty dishes. ‘She had this way that made you want to take care of her,’ one said to Kraus, with distaste. ‘She was very vulnerable and brought out your maternal instincts.’ ‘You never knew where you stood,’ another said. ‘Always putting everything into the mean typewritten letter she wouldn’t say to your face.’

‘Intention: I become a murderess by repeating in words the lives of other murderesses,’ Acker began her first great success in writing, The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula, distributed in monthly instalments as mail art in 1973. The good girl with the excellent education starts her assignment as she’s been taught to, with a proper plan. ‘I have no money I’m on the street I’m dying no one’s going to help me I puke I puke I cause whatever happens to me I get the fuck out of here’ – what sort of utterance is that? How much misery and horror can a single subject be made to take? ‘I have a child I hate children I don’t have a child Jean says she’ll scream.’ ‘Don’t read books about schizophrenia. I want to read books about schizophrenia, especially Laing’s books and the books from Kingsley Hall.’ Yeah, fine, if you must, whatever. ‘Now I’m two people.’ Oh, OK.

The art world loved The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula, and it’s easy to see why. There’s such energy and humour in the way it cuts and jumps between textual realities, the blunt, shocking statements of mad, impossible transformations: ‘I have a child I hate children I don’t have a child’; ‘Now I’m two people’; ‘I become a man and a woman.’ It’s sophisticated but also winningly naive. Acker would add more texts, some stolen, some self-penned and personal from her diaries, with generic characters stuck on top, like stickers on the covers: pirates, biker gangs, lesbian schoolgirls, child-snatchers. Plagiarism, as the good little scholar would have known, comes from the Latin plaga, ‘net’, and originally referred to the crime of kidnapping, especially of children. One dreadful thing, psychoanalysts say, about having had an awful childhood is that survivors can find themselves stuck there, unable to get out.

Kraus doesn’t go into much detail about Acker’s family, but the few facts she gives us are enough. Her mother’s mother, Florence Weill, was from an Austrian Jewish family, and inherited a small fortune from her husband, whose business had been making gloves. Acker’s mother, Claire, became pregnant at the age of 21, only to be abandoned by the baby’s father; whereupon it looks as though Florence did a deal with a man called Albert (Bud) Alexander, that by becoming Claire’s husband and the baby’s father, he also got a job for life. (Florence’s financial control over her daughter, Kraus notes with much perception, ‘was selective and punitive, as it often is in families of means’.) As well as Karen – who at some point became Kathy – the Alexanders produced a younger girl, Wendy, who isn’t mentioned in Kraus’s list of sources. ‘An unimportant torment,’ Acker called her in Great Expectations. ‘My sister … is the president … of her tennis club!’ she is said to have gasped on her deathbed, when friends tried to persuade her at least to ring her nearest relative and let her know she was ill.

Acker grew up in Sutton Place in Manhattan, and was a star pupil at the Lenox School, at that time ‘the only “white glove” Upper East Side private girls’ school that was widely open to Jews’. Classmates remember her as academically brilliant – ‘Modern Library editions of Dostoyevsky, Gogol, Turgenev’ – and also as ‘a mess’, with

the look of a young girl who was neglected. Not just that she didn’t care, but that no one cared. Not her mother or anyone else. Her shoes were scuffed, her clothes were ruffled, she smelled bad. Nobody ever went to Kathy’s apartment. The only time anyone ever saw her mother was at graduation. She was always in the margins, a shadow.

The schoolgirl Kathy was also known for her unusually early, much bragged about, sexual achievements. ‘I never knew who my father was and my mother disliked me intensely, so the first time I got affection, so to speak … one was from school because I was a good student, and the other was sexually. I lost my virginity very, very young and it was a way people loved me,’ she beamingly explained to Melvyn Bragg. ‘So I always identified sex and love.’ ‘At this point, I’m oversensitive and have a hard time talking to anyone,’ she would write in The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula. ‘I can fuck more easily.’ When she was 16, she had a summer of love with the film scholar P. Adams Sitney, who was about to go to Yale. ‘Sitney’s poetic passions that summer included Charles Olson, Ezra Pound, Virgil and Sextus Propertius.’ He also introduced his girlfriend to Andy Warhol, Jack Smith, Carolee Schneemann. ‘Her eyes opened wide.’

In later years, Acker often said that she had studied linguistics under Roman Jakobson. This wasn’t true, Kraus thinks: Jakobson taught at Harvard, which didn’t take girls until the mid-1970s. Acker applied to Radcliffe, and was, Kraus writes, ‘stunned’ to be rejected. Her second choice was Brandeis, known at the time as ‘Jew U’. She was a classics major, and her reading is evident in her adult work: there’s Propertius, Catullus, her Eurydice in the Underworld, and so on. She was fond of claiming that classical authors had never seen the need for originality in their narratives, so why should she?

Acker also claimed to have studied with Herbert Marcuse at the University of California at San Diego, but that doesn’t seem to have been true either. In fact she dropped out of Brandeis after two years to follow her boyfriend, Bob Acker, to UCSD, marrying him in the process. That’s just what you did, as Kraus says, as a co-ed in the 1960s, if you wanted to have sex and to get away from your parents, and Acker was clearly eager to do both. In San Diego she finished her BA and started at David Antin’s poetry seminar, where she met another student called Len Neufeld. The pair of them ran away from their respective spouses to New York City, with the idea of making it big as writers, just as Patti Smith had a couple of years before.

On arriving in New York, they looked around for jobs they could take to subsidise their writing – the minimum hourly wage at that time, Kraus has discovered, was $1.85. On the other hand, if ‘an attractive straight couple without drug habits who showed up on time’ were willing to perform in hardcore porn shorts, the rate was $100 daily, or, in a live sex show on 42nd Street, $120 for an evening’s work. As a plus, the sex shows offered some creative freedom. Acker’s hair was already short by this time, so she worked that into a Joan of Arc skit. Another involved a woman telling her psychiatrist about a predatory Santa. Acker and Neufeld worked at a club called Fun City for four months before it was busted and they were booked. A couple of years later, Acker – never one for what she called ‘robot’ employment – briefly supported herself by stripping, working in a massage parlour and tutoring Latin. ‘You see people from the bottom up,’ she said later of her experiences in the sex trade. ‘You see it in a different way, especially power relationships in society … And I think that never left me.’

Apart from trips to one dive or another to make money, Acker spent pretty well every hour God gave her in bed, writing or having sex or sleeping: she could sleep, Kraus reports, for as many as 16 hours a day. Why did she sleep so much? Youngsters do of course, but also a lot of the time Acker was ill. Within weeks of her return to New York, she was diagnosed with pelvic inflammatory disease, a trouble usually caused by a sexually transmitted infection. This being America, she had to pay for medical examinations and prescription painkillers and antibiotics. According to Acker in notebooks and published writings, she asked her family to help and they said no.

Standard management of such diseases involves tracing and treating the patient’s sexual partners, otherwise the bugs just go round and round. Nothing is said about this happening to any of the men with whom Acker was having sex. What we do know, from Kraus and others, is that Acker suffered repeated bouts of this debilitating illness throughout her life. And we know, of course, from the books Acker was writing, about the brutal injustices of gynaecological medicine in the early 1970s, a wrathful goblin outrider of the then blossoming feminist healthcare movement:

I move to New York because I write and want to meet writers. I have no money, no way of getting money, no friends in New York, no parents. I get Pelvic Inflammatory Disease, walk into Columbia Presbyterian clinic: woman vomits blood over floor … Slightly hallucinating doctor gives me four shots of penicillin in ass throws needle into my ass BAM ‘mm that one got in ok’ gives me endless bottles of synthetic opium and nembutal to shut me up. A month later I’m even sicker.

There’s more PID right at the beginning of Blood and Guts in High School (1978): ‘Janey fucks him even though it hurts like hell.’ That novel then proceeds to a report of the narrator’s first abortion, complete with itemised price list ($190 without a general anaesthetic, which costs another $50): ‘Having an abortion was obviously just like getting fucked. If we closed our eyes and spread our legs, we’d be taken care of.’

Except that it turns out not to be so simple. ‘Abortions make it dangerous to fuck again because they stretch out the opening of the womb so the sperm can reach the egg real easily … They leave gaping holes in the womb and any foreign bodies near these holes can cause infection.’ But obviously ‘all the boys I fucked refused to wear condoms,’ so back the narrator comes for a second abortion a couple of months later, and then, the week after, suffers more pain from PID. Acker, Kraus reckons, underwent ‘at least five’ abortions, and many, many more PID flare-ups. A friend recalls ringing her one night in 1994 and finding her on the point of suicide from misery and pain.

‘Abortions are the symbol, the outer image, of sexual relations,’ Acker wrote in Blood and Guts in High School. ‘Describing my abortions is the only real way I can tell you about pain and fear.’ ‘In book after book,’ as Kraus puts it,

Acker would describe the cyclic despair of doing sex work to buy medicine so she could keep on doing sex work, crafting these months of her actual life into something more allegorical … Acker worked and reworked her memories until, like the sex she described, they became conduits to something apersonal, until they became myth.

But for Acker, abortions and illnesses are outer symbols of other things as well. Abortions, especially in America, tell us whether a state values its people, in particular its female people, enough to give them access to decent, non-judgmental healthcare, a matter on which Acker’s views are completely clear. And given her appalling experiences with doctors and hospitals – given, too, the lack of concern her parents and, one suspects, her sexual partners showed for her and her health – it’s surely not surprising that she came increasingly to rely on alternative therapies and general health-freakdom in order to assert some power over her wellbeing and physical destiny.

She spent vast amounts of money on astrology and nutritionists and psychics, Reiki and Rolfing and the rest. Even when she was earning very little, she insisted on staying in expensive hotels and eating the finest and rarest of vegetarian goodies: ‘braised cabbage in juniper berries … and some beautiful red lettuce’, and so on. If you’ve picked up the idea that there’s no one, nothing out there that will look after you when you need it, of course you’re going to do whatever you think is in your grasp to look after yourself.

Acker’s first cancer scare came, Kraus reports, in 1978, while she was working on Blood and Guts in High School. ‘Fear and dread of the disease,’ as Kraus says, ‘course through the book’:

Having cancer is like having a baby. If you’re a woman and you can’t have a baby cause you’re starving poor or cause no man wants anything to do with you or cause you’re lonely and miserable and frightened and totally insane, you might as well get cancer. You can feel your lump, and you nurse it, knowing it will always get bigger … Cancer is the outward condition of the condition of being screwed up.

She married her second husband, the composer and musician Peter Gordon, ‘in the throes’ of this first scare, in an attempt to get coverage from his medical insurance, but the lump turned out to be benign. It would be the first of several until the discovery, in 1996, of a lump that wasn’t.

‘At that time,’ Acker wrote in her essay ‘The Gift of Disease’, published in the Guardian at the beginning of 1997, ‘I was working as a visiting professor at an art college and so did not qualify for medical benefits … I would have to pay for everything out of my pocket. Radiation on its own costs $20,000; a single mastectomy costs approximately $4000. Of course, there would be extra expenses. I chose a double mastectomy, for I did not want to have only one breast. The price was $7000.’

The cancer, however, had invaded several lymph nodes. Acker elected not to pay for chemotherapy, which ‘begins at $20,000’, but to rely on her healers, in particular a past-lives regressionist, who suggested that if she explored her memories of her life in her mother’s womb, she might find a way to heal herself. It seems from the Guardian article that Acker believed them and that she believed she no longer had cancer. The article was illustrated with beautiful photographs by a friend of Acker’s, Del LaGrace Volcano. In one, a gaunt Acker defiantly twists to display her newly flattened chest. In another she is wearing a massive furry garment that spreads out from her shoulders like wings.

‘My search for a way to defeat cancer now became a search for life and death that were meaningful,’ Acker continued in the article. ‘I had already learned one thing, though I didn’t at the time know it: that I live as I believe, that belief is equal to the body.’ Had she not read Illness as Metaphor, the great work of her fellow New York intellectual Susan Sontag? Reclaiming the meaning of one’s own life is one thing, but seeking succour in sympathetic magic is another. Was it perhaps that Acker had already used cancer so much as a metaphor in her writing that when she came to confront it as a material disease, her terror of ‘the whitecoats’ – as she always called them – had her trapped?

There’s something else terribly sad in this essay. It’s quite long, and has lots of info about several professional healers, but actual friends are mentioned only once: ‘many of my friends phoned me, crying and yelling.’ ‘My lover’ appears in one scene, then is forgotten – Acker had started a relationship with the British music journalist Charles Shaar Murray, and had moved back to London to be with him in the summer of 1996. Acker might even, Kraus thinks, have been entitled to free NHS treatment, except that she and Murray were forever falling out, and Acker kept flying back to the US.

In September 1997, she performed pieces from her last novel, Pussy, King of the Pirates, with music from the Mekons at the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art. During the final performance she collapsed. She got herself to San Francisco, where she booked a room in a Travelodge and phoned Glück, and then Viegener. A hospital examination found cancer had spread throughout her body. She wanted to go to the Gerson juice-and-colonics place in Tijuana, but she was so ill it wouldn’t take her. Viegener found a less fashionable clinic that did.

Kraus’s account gets quite sparse at this point, for an interesting reason, maybe, that takes us back to the Society of Friends. This is ‘the first authorised biography’, it says on the book’s press release, and so it is; but it is not the only one. Viegener has also authorised another, by the Canadian journalist Jason McBride, whose book was originally intended to come out this year as well. In the event, McBride expects it to take him at least until next year to finish writing, but in the meantime he has published a couple of exhaustively researched articles on the internet: one about Acker’s adventures in Toronto in the 1970s (with an amazing photo of a square and scrubbed-looking young pixie in tights and an Aran jersey) and one about the death, which is where the detail about her sister and the tennis club comes from. ‘I did everything I could for both writers,’ Viegener told me, ‘so if I shared something with one I’d send it to the other’; he also put Kraus and McBride in touch with each other, and Kraus thanks both men in her book. Viegener published some of his own thoughts about Acker’s death in an online journal in 2004, and will publish an expanded version as a chapbook later on this year.

The early 1980s were such a strange time, if you were young and looking around the media for ideas about women and what women might do. It was as though there could be one and one only of each available option: one politician, Margaret Thatcher; one princess, Princess Di; one blonde superstar, Madonna; one lean and androgynous rock’n’roll performer, Patti Smith. In Kraus’s view, Acker went along with this weird logic, too. ‘Acker is in London, at a peak of notoriety that only certain literary men enjoy,’ she wrote in her marvellous third novel, Torpor (2006). ‘She’s accomplished this by distancing herself from all the dowdy women … Acker understands that writing, without myth, is nothing and female myths don’t run in groups.’

Blood and Guts in High School, Plus Two was published by Picador in February 1984. The ‘plus two’ were Great Expectations and My Death, My Life by Pier Paolo Pasolini. (The current Penguin Classics edition drops both, and is remarkable for being one of few Acker books ever published to have a photo of a crop-headed young woman on the cover, except that it isn’t Acker, but a William Claxton shot of Peggy Moffitt. Why?) I don’t recall anything about the South Bank Show that April, but I do remember the lifesize Acker cut-outs in high street bookshops, and clocking Acker’s artful and expensive-looking clothes (Comme des Garçons, Vivienne Westwood): some sort of child actor sock-puppet arrangement, I suspected, with Malcolm McLaren lurking in the background, an Annabella Lwin of literature – and wasn’t Westwood dressing everybody in pirate outfits at this time?

I was completely wrong, of course. The truth behind the clothes was that Acker had bought them, bought them and lots of other fabulous items, ready for what she planned to be her UK debut as Lady Lazarus, rising from the wreckage of her family: her stepfather, her mother and her grandmother had all died within a few years. She must have been both liberated and devastated. The important thing, though, was that the deaths had left her rich.

Acker’s stepfather died of a heart attack in 1977, leaving Claire helpless, with ‘no occupation or income except for occasional gifts or loans from her mother’, Kraus says. She blew what she had on shopping, drink, diet pills and evenings at Studio 54, then killed herself in a room at a nearby Hilton on Christmas Eve, 1978. ‘Friends of Acker’s vaguely recall her frantic search for her mother, which went on for days, even weeks.’ Florence died ten months later, leaving an estate of just under a million dollars, the bulk of it divided equally between Acker and her sister. Acker got working on the novel she would call Great Expectations, in which she would plagiarise, among others, Dickens, Propertius and Pierre Guyotat’s monstrously abject and disjointed Algerian War memoirs. Running through the middle, as Kraus says, was a stream of grotesquely skewed autobiography: ‘the threat and promise of inheritance … like the River Styx’.

It was a bit from Great Expectations that Kraus herself saw Acker perform at the Mudd Club in New York in February 1980: the ‘Open Letters’, to Sylvère Lotringer, Susan Sontag and others. ‘Dear Sylvère, This serves you right … Now that I’ve spent last night fucking you, I’m in love with you.’ ‘Dear Susan Sontag, Would you please read my books and make me famous?’ ‘Her performance,’ Kraus remembers, ‘was indelibly charming and brazen.’

Acker, Kraus explains, had not originally planned Blood and Guts in High School as a continuous novel. It was a collage, an assemblage of routines and riffs. The title, obviously, is a joke, and part of that joke is that it all sounds so generic. That surf-garage-art-punk infantilism you can hear in the title was common in the New York art world of the 1970s, especially after the Ramones made their CBGB debut in 1974. ‘I’m becoming a rock’n’roll lyricist!’ Acker wrote to the L*A*N*G*U*A*G*E poet Ron Silliman that year, with a version of her own: ‘NO MORE PARENTS NO MORE SCHOOL/NO MORE SOCIETY’S DIRTY RULES/SPREAD MY LEGS I’M SO POOR I WANT TO DIE.’

I bought and read Blood and Guts in High School in the 1980s, and was interested to find I remembered a great deal about it when I read it again. It also seemed to have improved a lot from the laying down. Some bits I remember as shocking, crude, abrasive now just read as clever, funny, rich:

1. Janey Smith, in the first section, described as ‘ten years old, living with her father’, whom she thinks of ‘as boyfriend, brother, sister, amusement’, and who wants to leave her for ‘Sally, a 21-year-old starlet’. Which is to say, the art-punk infantilism of the title continues. The novel was banned in West Germany for its child sex references but, actually, it’s plain that the Janey-and-her-father conversations come from real-life sexual jealousy and bickering between consenting, if bratty, adults. By distorting the ages of the protagonists in the way she does, Acker does something analogous, maybe, to putting a bit of fuzz on a guitar: the mean, cold parents, the wailing, desperate children inside us all.

2. Crude graffito-like drawings of penises, more penises, a crotch in a jockstrap, ‘my cunt red ugh’. One reviewer once wrote that reading Acker was ‘like reading some lecture notes … written by a bored student, with genitalia and “I love Peter” doodled in the margins’. Which is true.

3. The speedy recourse to disgust and self-disgust: ‘my cunt red ugh’. Acker writes a great deal about sex, her genitals and those of others, but seldom with a tone of appreciation or enjoyment. Roz Kaveney, the London-based writer and trans activist who knew Acker well, remembers her reassuring male lovers that, secretly, she found women’s genitals ‘kind of yucky’. ‘She also said the same thing to women she slept with about men’s pricks.’

4. The Lousy Mindless Salesgirl in the hippy bakery. In 1977 or so, Acker did this job, in spite of her views on robot employment. The poet Eileen Myles has a bit in Inferno (2010) about seeing her there. It’s interesting to discover that forty years ago, it was all coconut oil and carob, organic everything and wheatgrass juice as a cure for cancer: everything changes except the wellness industry and its fads.

5. The dream maps and other drawings, diagramming hippyish psychic layerings and connections: animal tracks, a flight path, a temple with a fancy cornice, ‘a tree which is the world which is my back’. Acker drew these by hand in her notebooks, and coloured them in with what looks like felt-tip pen. The originals are in the Acker archive at Duke.

6. Janey’s book report on Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1850 sex-and-tattooing classic The Scarlet Letter, in which ‘the young handsome reverend’ called Dimmesdale is changed to Dimwit, and yells at Hester that she is ‘the worst piece of trash-cunt who ever lived’. Hope, as in the original, is reserved for Hester’s daughter, Pearl, who is four years old and ‘wild as they come’, with ‘wild in the puritan new england society Hawthorne writes about mean[ing] evil anti-society criminal’.

7. The Persian poems: bits ostensibly copied, in Acker’s handwriting, from a Farsi grammar. It’s interesting that Acker did her little ‘e’s like backwards 3s regardless of which language she was learning, and most of her little ‘m’s with an extra hump.

8. With Jean Genet in Tangier. Genet, for Acker, was a key figure in what she calls ‘that tradition’, ‘the other tradition’, ‘the non-acceptable literary tradition’, ‘the tradition of those books that were hated when they were written and … present the human heart naked so that our world, for a second, bursts into flames’.

One reason , Kraus has said, that she wanted to write this book was to correct what she calls the ‘horrifying’ disparity between reality and myth in recent memoirs and coffee-table surveys of what she calls ‘Olde Tyme New York’. In her novel I Love Dick (1997), for example, Kraus had the artist Eleanor Antin (b. 1935) explain why so many of her friends had settled in Manhattan in the first place: ‘Studios were cheap, so were paint and canvases, booze and cigarettes. All over the Village young people were writing, painting, getting psychoanalysed and fucking the bourgeoisie.’*

Antin was a good friend of Acker’s and a major influence on her early work. It was Antin’s idea to do the Black Tarantula pieces as mail art, and Antin’s list of art world contacts that Acker used. And it was Antin’s husband, David, who suggested to Acker the techniques of appropriation and assemblage that became the basis of her lifelong practice when she was in his poetry class at UCSD. When he was teaching at San Diego, David Antin, according to Kraus, was looking for a way not to have to read hundreds of awful student poems; the solution he hit on was to adopt ‘a quasi-Oulipan rule’. ‘Go to the library and steal it,’ he told his students. ‘Go to the library, find someone who’s already written about something better than you could possibly do at this moment in your life and we’ll consider the work of putting the pieces together like a film.’ ‘The idea,’ Kraus glosses, ‘wasn’t just to cut and paste things by rote, but to find the connections between disparate realities.’ One example involved Aeschylus and a plumbing manual. ‘You could make it be like a car collision,’ Antin said, or ‘you might want to slip things into each other, as if Aeschylus was being sodomised by the plumbing manual.’ Or the other way about.

‘Since wanted to be a writer,’ Acker wrote in an anguished piece called ‘Dead Doll Humility’ (1990), ‘tried hard to find her own voice. Couldn’t. But still loved to write. Loved to play with language. Language was material like clay or paint.’ ‘I never thought I had imagination,’ Acker said in 1991. ‘I wrote so many pages a day and that was that. I set up guidelines for each piece, such as you’ll use autobiographical and fake-autobiographical material, or you’re not allowed to rewrite. I really didn’t want any creativity. It was task work and that was how I thought of it.’ One side-effect was that Acker came to have ‘enormous respect’ for the productivity and staying power of pulp writers such as Harold Robbins. She admired Robbins so much that she folded bits from The Pirate into her small-press serial The Adult Life of Toulouse Lautrec (1975).

‘I was very interested in the use of the “I”,’ she told a journalist in the mid-1970s, discussing The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula.

So I went to the UCSD library … and took out whatever books about murderesses I could get … Only I changed the third person to the first person, so they’d seem to be about myself. And then I set up sections within parentheses what were just diary sections … So there were two I’s in the book, the I without the parentheses and the I within … Gradually what happened was the two I’s started playing games with each other, becoming one.

‘The experiment works,’ Kraus says; it’s ‘a light-hearted act of Artaudian cruelty. Almost magically, the diary writings Acker had been trying so hard to lift into poetry are transformed into literary matériel … What’s remarkable about this early work is the intensity Acker arrives at: accessing fleshy, emotive fragments of female experience within a framework of formalist rigour.’ All of this is true.

Other readers read the book differently, David Foster Wallace for one. ‘I’m hoping that for anybody who tries to evaluate and articulate the valuable qualities of the fiction s/he likes to read, some authors present the thorny problem of possessing value without displaying much quality’: Wallace was reviewing a 1992 omnibus of Acker’s early serial novels. ‘All of them are at once critically pretty interesting and artistically pretty crummy and actually no fun to read at all.’ Which is also true, and was a problem that only got bigger as Acker’s career progressed.

Somewhere between Blood and Guts in High School and its follow-up, Don Quixote (1986), Acker, Kraus judges, started getting ‘lost’. ‘She started out thinking that the first section of Don Quixote would approach Nature by tracing the writings and life of the 19th-century British agrarian working-class poet John Clare,’ but letters to the writer and theorist Peter Wollen, her main married-man lover of the period, show her flailing: ‘I must get there, out of this endless selfishness a problem with always watching oneself … the autocratic autistic world that I MUST penetrate into nature … The methodological rigour is absolutely meaningless. So what will happen with this meaninglessness?’ There’s lots more.†

John Clare is completely absent from the published novel, which can be read as a battle royal with artistic solipsism and personal loneliness:

When she was finally crazy because she was about to have an abortion, she conceived of the most insane idea that any woman can think of. Which is to love … She would love another person. By loving another person, she would right every manner of political, social and individual wrong: she would put herself in those situations so perilous the glory of her name would resound.

Acker seems always to have found ‘fucking’ easier than friendship: how to do it, who with, how to stop it spoiling, which seemed to happen often, when she started getting bored. The problem was particularly acute in London, because of geographical and cultural distance partly, and also because of her success. Kaveney remembers Acker having friendships with some peers and contemporaries, Jeanette Winterson, Neil Gaiman, Alan Moore, Geoff Ryman, Kaveney herself; but she was susceptible to ‘Ackerlites’ and could herself be a bit of a climber and a user. ‘Neil remarked … that I was more important to Kathy than I realised,’ Kaveney writes. ‘You were her trophy weird friend.’ Acker liked to be seen with weird friends, Gaiman told Kaveney, because they gave her ‘street cred’.

And there were problems of artistic direction. In spite of her fame and a formidable work ethic, Acker found it next to impossible to earn much money, or to hit a balance between serious appreciation and succès de scandale. An LRB piece by Danny Karlin (2 June 1988) suggested that ‘agents and publishers’ used Acker and her work to peddle ‘ultimate outrage’ as a commodity, and looking back at her life in London, Acker seemed to agree. ‘I’m very well known, and I get tons of work. But to say that they like what I do? No, I wouldn’t say that. They fetishise what I do.’

Up to Don Quixote, Kraus thinks, Acker’s work was full of sex as ‘psychological displacement, power play, social comedy, the glorious sexual revolution’s default means of exchange’. But then she started moving towards something more ‘essentialist’, by which Kraus means, I think, solemn and sacral. ‘I have no self,’ Kraus quotes from Don Quixote, ‘I won’t go against the truth of my life which is my sexuality.’ In 1986 Acker met a man she called ‘the Germ’ or ‘the German’, who was indeed German, and into complicated scenarios involving BDSM and control; that relationship absorbed much of her energies for the next four years. And another reason, Kraus thinks, that Acker gravitated towards London’s BDSM scene was that it was full of feminists who stuck up for her throughout the many attacks on her work from the more puritanical anti-porn end of the women’s movement; Kaveney, however, remembers her not being that keen on joining in with crowd-pleasing activities, such as ‘mass whippings to the Ride of the Valkyries’. Perhaps, Kaveney thinks, ‘what Kathy liked … was a sheer sense of being on the edge of oblivion and danger, and there was not much existential angst to be had down at Maitresse.’

In 1989, Acker’s UK publisher put together a greatest hits of early material, calling it Young Lust. It included The Adult Life of Toulouse Lautrec, with its four-page Harold Robbins tribute. One of Robbins’s people took the matter up with the publisher, Pandora, which was owned by Unwin Hyman. What happened next is not entirely clear, except that Acker was left feeling unsupported and unloved. She gave up her flat in London and bought a hugely expensive loft in Greenwich Village – ‘a folie de grandeur’, Kaveney has said, ‘from which her finances never entirely recovered’. In June 1990 she also bought her flat in Brighton. Towards the end of that year she got the job she mentioned in her Guardian essay, at the San Francisco Art Institute, and rented an apartment nearby. Her net salary from SFAI, Kraus calculates, didn’t even cover her San Francisco flat, and by this point she had run through about half of the money her grandmother had left her.

In San Francisco, Acker seems to have liked her students, and to have thrown herself into student subculture with enthusiasm. She joined in mosh-pits full of women with no tops on. She took her classes to Harry Dodge and Silas Howard’s Bearded Lady Café. She got herself more tattoos, and piercings, including two in her labia. And a motorbike:

I’m a girl. And there’s this big hot throbbing thing between my legs, whenever I want/him/her, and he/she’s mine and won’t reject me like humans have the habit of doing … It is so cool. To be on/around this thing and there are trees and water all around you, flying through the country, something like freedom. That’s the decent side of the American nightmare.

‘She was drifting further and further away from her former New York contemporaries,’ Kraus writes, ‘into a phantasmic but prescient realm of wild girls, brigands and pirates: a subculture born from increased family anarchy and personal trauma.’ (‘I know my students,’ Acker wrote in an email to a friend. ‘I know that over half of them come out of serious child abuse, sexual and other.’) And she also seems to have been drifting deeper and deeper inwards, into the exaltation and derangement that gets written about by Bataille and Laure and so on. She talked about writing while masturbating with a vibrator, ‘losing control of the language and seeing what that’s like’. ‘I didn’t know my body could do this,’ she said about the trance states she experienced while getting piercings. ‘It’s not exactly pleasure. It’s more like vision.’

‘The KATHY ACKER that YOU WANT (as you put it),’ she wrote in 1995 to the Australian theorist McKenzie Wark, ‘is another MICKEY MOUSE … It’s media, Ken. It’s not me.’

Another email, sent earlier that same morning. ‘I’m so unused to anything but overwork and lust that I wouldn’t recognise a cat if I fell over it … I’m sorry, Ken; do be my friend.’

‘A few years ago , the writer Chris Kraus, author of I Love Dick, found that her own experiences were becoming more and more like Kathy’s,’ it says on the front flap of After Kathy Acker. ‘She began writing about Acker “through the distance, but with this incredible frisson of feeling that often I could write ‘I’ instead of ‘she’”. This is “literary friction”.’

What strange, insinuating things to put on the cover of what seems to be a perfectly straightforward, conventionally put together literary biography. Does Kraus confuse her own experiences with those of Kathy Acker? No, she doesn’t. Does Kraus write much about herself in the book? Not at all. She does say she saw Acker read at the Mudd Club in 1980; she does venture a few critical evaluations. And she does occasionally betray the odd note of dislike and disapproval, the latter mostly regarding what she obviously sees as Acker’s hopelessness with money. Kraus writes a lot in her own novels about money matters, and had she had a windfall like Acker got, would probably by now own every apartment building in New York.

Except that’s not really it at all, now, is it. I Love Dick, Kraus’s first novel and the book that made her famous, largely starred the author playing herself, Chris Kraus, along with her husband of the time, Sylvère Lotringer, the founding editor of Semiotext(e), the avant-garde New York journal and small press. Lotringer was, obviously, the Sylvère to whom Acker wrote that Mudd Club ‘Open Letter’, and with whom she was ‘close friends and lovers’, Kraus says, ‘between 1977-1980’. Kraus fans may remember that bit in I Love Dick when Chris opens one of Sylvère’s books and it’s inscribed from Acker ‘to Sylvère, The Best Fuck In The World (At Least To My Knowledge)’. It survives, with much the same wording, in Jill Soloway’s Amazon sitcom version of the book.

I Love Dick, of course, is famous partly because it transgresses the transgressors, blowing Kraus’s privacy, and Sylvère’s, and that of the love-object, as it goes. Was there once an idea that the Acker book would screw with the etiquette of literary biography in some similarly meta way? ‘For weeks I’ve been carrying around three of the late Kathy Acker’s notebooks,’ Kraus wrote in an essay in 2001. ‘As objects, they’re in what the Tibetans call a “Bardo” state.’ So she did appear to be researching some sort of Acker book at that point, something she has recently confirmed, adding that she had to drop it because ‘it would’ve been a disaster … I wouldn’t have had enough distance.’

It might also have been ‘a disaster’ for Kraus’s own fiction, because when you read a lot of Acker, suddenly you realise where so much of I Love Dick comes from. The butting together of sex and theory and comedy and abjection; the embarrassing gossip about real, named people – the ‘chamber novel’ aspect, as Kraus likes to call it, referencing Sei Shonagon and La Princesse de Clèves – and above all (‘Dear Susan Sontag, Would you please read my books and make me famous?’) the whiny epistolary form. Except that even as I Love Dick progresses, you can see Kraus pull away into the wry, cool middle distance that allows her in her subsequent – and much more interesting – writing to explore ideas and spaces and textures that Ackerish wailing and stamping would miss. By waiting until she had written Torpor (2006) and Summer of Hate (2012), Kraus has allowed plenty of clear blue water between herself and her onetime influence. She’s also given what must be her own strong feelings time to calm down and mature.

What remain strange, though, are the things that Kraus chooses not to mention. My Mother: Demonology (1993), for example, which has letters addressed to ‘Bourenine’, who is, Kraus has already told us, ‘a cipher’ for Lotringer and which ends with a hellish authors’ tour of Germany: ‘Bourenine’s wife is scheduled to join the tour tomorrow night. When I began to cry, I realised that I was out of control.’ ‘Kathy was always such a bitch,’ Eileen Myles writes in Inferno about this adventure. ‘She was having some drama with Sylvère so she was indirectly torturing Chris (Kraus) who was entirely obsessed with her.’ You can sort of see why Kraus hasn’t detailed all this – it’s so trivial, and so horrendously tangled. Except that isn’t all this trivia and entanglement exactly the stuff she says she likes?

What matters most, though, as Kraus said recently, is ‘how history speaks to the present’. So what is it that Kathy Acker is saying, to us, right now? When I first read I Love Dick, it gave me the strangest sullen feeling, as if it had thrust me straight back to school: yes, yes, the feeling said, I know you’re thinking it’s all going on a bit, but actually, it’s performative philosophy. It’s rigorously crafted and precise. It was tracing that feeling back, to my younger self as a reader in the 1980s, that made me realise how much Acker there is curled up inside that book. Tedious mess or rigorous experiment? Art or ranting? What if the really great thing Acker’s work is saying is that it can be both?

‘Oh they’re structured, they’re carefully structured,’ Acker told Lotringer in a long interview from 1991. But when Picador published Blood and Guts in High School in 1984, somehow they got the last two chapters in the wrong order, ‘and no one noticed, so I guess it’s not the most tightly structured book after all’. What ending had Acker wanted? What ending did Picador think she wanted? In the ending that was printed, Janey dies and then there are pages of Book of the Dead stuff, then the births of lots more Janeys, ‘and these Janeys covered the earth’. And finally, as a sort of coda, there is a little song that starts ‘Blood and guts in high school/This is all I know/Parents, teachers, boyfriends/All have got to go’ and which I’ve now been singing, to the tune of ‘Morningtown Ride’ by the Seekers, for weeks.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.