Chris Kraus , a 39-year-old experimental film maker, and Sylvère Lotringer, a 56-year-old college professor from New York, have dinner with Dick ____, a friendly acquaintance of Sylvère’s, at a sushi bar in Pasadena. Dick is an English cultural critic who’s recently relocated from Melbourne to Los Angeles. Chris and Sylvère have spent Sylvère’s sabbatical at a cabin in Crestline, a small town in the San Bernardino mountains, some 90 minutes from Los Angeles. Since Sylvère begins teaching again in January, they will soon be returning to New York. Over dinner the two men discuss recent trends in postmodern critical theory and Chris, who is no intellectual, notices Dick making continual eye contact with her … So go the first eight and a half lines of Chris Kraus’s scandalous novel, first published in 1997 and now reissued. I’ve copied them out word for word.

Dick doesn’t know it yet, but Chris is fondly, profoundly bored in her marriage, her career – which is going nowhere – and in the role she seems to have got herself stuck in, as plus-one and helpmate to a powerful older man. She’s bored, she’s nearly forty, and she’s all set to blow a gasket, with Dick a man-size ‘transitional object’ who happens to be in the way. He flirts, he drives a T-bird, he has, she senses, ‘a vast intelligence straining beyond the po-mo rhetoric and words’; and so begins a mad, unrequited infatuation, conducted mainly in letters to him, though the letters describe some phone calls and actual meetings too. The novel also proceeds mainly in the form of these letters, linked with brash, pop-arty third-person exposition: ‘Chris was so embarrassed. She wondered if the call was really for Sylvère, but Dick didn’t ask for him, so she stayed on the scratchy line.’ It begins with the dinner in the sushi bar and ends nine months later, when Dick for the first and only time writes back.

There’s a little more to say about the novel’s provenance at this point. Sylvère Lotringer is the name of a real person, a real Columbia University professor, now retired. In the late 1970s he founded Semiotext(e), the magazine and, later, book imprint that brought Deleuze and Baudrillard and many others into currency among English-speaking 1980s hipsters; he was also known ‘at the Mudd Club’, Kraus tells us, ‘as the philosopher of kinky sex’. Kraus too appears in real life much as she presents herself in her novel: Connecticut-born but brought up in New Zealand, a former performance artist and topless dancer, founder of Semiotext(e)’s Native Agents series, which publishes work by mostly female writers, such as Lynne Tillman, Shulamith Firestone, Eileen Myles. And Dick, though never given a surname in the novel, was immediately outed in New York magazine as the English writer Dick Hebdige, a former star student of Stuart Hall’s at the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies and the author of a great book about the 1970s punk-reggae crossover, Subculture: The Meaning of Style (1979).

Hebdige, Kraus has said, was ‘appalled’ to hear what she had done with his likeness in her novel. As far as I know, he has never spoken about the matter in public (I wrote to him myself while I was working on this piece but true to character, he didn’t write back). He’s currently a professor of film and media theory at the University of California at Santa Barbara and hasn’t published more than a handful of essays since 1988. Kraus and Lotringer still work together but are no longer married. Kraus has written three more novels and two books of art criticism, and has become a fairy godmother figure to a generation of younger women writers, who admire her for writing openly and with humour about sex and gender and power and abjection. I Love Dick is ‘the most important book about men and women written in the last century’, Emily Gould claimed a couple of weeks ago in the Guardian. ‘Deeply feminist, formally both out of control and expertly in control,’ Sheila Heti wrote in the Believer in 2013. ‘Once it came into my hands it didn’t leave them until the book was done.’

So back to the basic setup: 3 December 1994 is the date of the primal sushi dinner in Pasadena. It’s followed by much alcohol at Dick’s house, and a wee-hours screening of our host in an unimpressive video, dressed up as Johnny Cash (‘I’m a sucker for despair, for faltering’). ‘A conceptual fuck’ is the way Chris describes her experience of the evening over breakfast the next morning; she then goes on obsessing and obsessing. And Sylvère indulges it, maybe because it’s a good excuse for him not to be getting on with his Holocaust book and maybe because, ‘for the first time since last summer, Chris seems animated and alive,’ not to mention ‘sexually aroused’.

The letters are actually Sylvère’s idea, and, a few days later, it’s Sylvère who writes the first one, establishing the ground rules for the game: ‘Dear Dick, it must be the desert wind that went to our heads that night …’ ‘I’m thrown into this weird position,’ Chris writes in her letter. ‘Reactive – like Charlotte Stant to Sylvère’s Maggie Verver, if we were living in … The Golden Bowl.’ When they finish their letters both feel they could do better. They’re ‘delirious and ecstatic’, ‘blissful and exhausted’, ‘finally inhabiting the same space at the same time’.

If Sylvère is involved, the correspondence is arty and high-falutin, a playful triangle of mimetic desire and homosocial gazes and so on: ‘So I got really involved in the fantasy, erotically too. If I wasn’t going to be jealous, my only choice was to enter this fictional liaison in a sort of perverse fashion,’ he claims. One letter he writes in the persona of ‘Charles Bovary’. ‘What does your name stand for, Dick?’ he writes in another, with the sign-off, ‘Here is mine.’ The letters might make an interesting art piece, he proposes – ‘a Calle Art piece. You know, like Sophie Calle?’ They could paste the letters to the cactuses in Dick’s garden while filming Dick’s reaction. They could publish them in book form and get Dick to write the introduction (‘PS Could you Express Mail us a copy of your latest book?’).

Chris tries her best with Charlotte Stant and Maggie Verver, but chirruping about Henry James novels isn’t really what she’s all about. ‘The Dumb Cunt’ is more her style, ‘a factory of emotions’; her passion has sent her back into adolescence, ‘hunched up in a leather jacket’, listening to the Ramones. She’s creeped out – understandably – when Sylvère secretly tapes Dick talking on the phone: ‘Such a violation,’ she thinks, recalling other creepy things her husband has done. And yet, she seems OK with writing about ‘methods of disposing of dead bodies’ and asking: ‘Dick, did you realise you have the same name as the murdered Dickie in Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley books?’ You can get away with this sort of thing in music sometimes – in the Ramones, crude and stupid is sometimes good. It looks awful in a book, though, and, nowadays, such messages addressed to an individual look stalky and troll-like (this must be one reason for the book’s current rediscovery: like drinks in jam jars and listening to vinyl, nostalgia for a less cyborganically complex world).

This first part of the book is called ‘Scenes from a Marriage’, and what an interesting, emblematic marriage it is. On the one hand: well, Semiotext(e) in the 1980s, ooh la la. Chris calls Guattari ‘Félix’; David Byrne is doing the music at Joseph Kosuth’s 50th birthday party, which gets written up the next day in the New York Post. ‘You think we’re decadent sophisticates,’ they write to Dick at one point, faux indignant, going on to explain that they’re about to leave California to go back east again, ‘for about the hundredth time in the last two years’: Sylvère is off to Paris and thence to their ‘other (rented) house in East Hampton’ and then they’ll kick back at their main house in the town of Thurman, upstate; they also have an apartment in the East Village. Chris drives from LA to New York cross-country, and writes about catching a bus to Guatemala City, and ends the book back in LA.

On the other hand, Sylvère, we learn, grew up in a working-class Jewish family in Paris, a child survivor of the Holocaust. His 85-year-old mother sews banknotes into a moneybelt to help him pay his mortgages. He’s in constant pain because of his plastic hip. Chris, meanwhile, suffers terribly from Crohn’s disease, which tends to worsen when she feels despairing. That’s the main reason Sylvère married her in the first place, so he could put her on his health insurance; but then, ‘our friendship strengthened, our love increased and sex was sublimated to more worthy social endeavours: art, career, property,’ as Sylvère writes when he’s pretending to be Charles.

The financial details of the arrangement are amazing. Chris, she has discovered, has a talent for operating as ‘a money-hustling hag’: noticing how admired her husband is among ‘young white men drawn to the more “transgressive” elements of modernism’, she sets about ‘milking money’ from these ‘Bataille Boys’, renting out Sylvère’s attention for ever higher fees. She invests the money in real estate, buying unpleasant properties in disappointing locations, nearish to the great cultural centres everybody wants to live in: ‘Considering Thurman as their “home” was a provisional delusion … it was a woodframe rural slum, trashed by a family of deadbeat hicks.’ Kraus subsidises her art, in other words, with rental income and property deals. One likeable thing about her is that she’s quite open about it, in this novel and elsewhere.

The marriage is so miserably stuck and packed with sadness, it becomes a sort of comic schtick – ‘a pair of clowns … Bouvard and Pecuchet, Burns and Allen, Mercier and Camier’, as Kraus put it in her third novel, Torpor (2006). A suicide pact is posited at one point but rejected, and then, as often happens, it’s a tiny thing that finally pierces the balloon: Kosuth’s 50th, when Chris finds her name missing from the guest list. And so, on Monday, 30 January, off she goes.

Part II of the book is called ‘Every Letter Is a Love Letter’. In it, Chris starts to pursue Dick for real, with a one-night stand in which Dick comports himself as so much the classic morning-after rotter, one can only hope it’s fiction, though it certainly reads like fact. Hurt rises off the page like vapour, bringing memories of earlier disasters: the one who told her to ‘swallow this mother’, the one who told her she wasn’t good-looking enough to be with him. Reading these bits, I was thrown straight back into all my own most humiliating memories – a small, square pit of such depth and horror, I couldn’t imagine how I’d ever escaped it. I suppose the bigger point is that in some ways we never do.

Thankfully, Dick and sex with Dick become less and less the point of Part II. Now Chris has started writing, she finds she likes it, and there’s so much she has to write about, perhaps she’ll never stop. The letters get longer, and take longer and longer to finish, and start taking in reviews and stories. ‘Dear Dick’ becomes ‘DD’ – ‘you’ve become Dear Diary’ – when it’s not missed out. ‘DD, Art, like God or The People, is fine for as long as you can believe in it.’ ‘Oh D, it’s Thursday morning, 9 a.m.’ ‘Dear Dick … What happens between women now is the most interesting thing in the world.’

The first letter takes off from a show of Olde New York photographs and is a bit like the Shakespeare’s Sister part of A Room of One’s Own. Kraus remembers artists she used to know who never made it: the ones who gave up or got evicted, or died of Aids or ‘killed themselves at the beginning of the onset so they wouldn’t be a burden on their friends’. The second letter cuts between the meeting during which she and Dick get it together (‘We have sex ’til breathing feels like fucking’) and a trip Chris takes to Guatemala, in pursuit of Jennifer Harbury, an American lawyer who at the time was on hunger strike in an effort to uncover the whereabouts of her guerrilla-commandante husband (‘Her heroic savvy Marxism evoked a world of women I love – communists with tea roses and steel-trap minds’). The third, ‘Kike Art’, is mainly about the 1995 R.B. Kitaj show at the Met, with asides about Simone Weil and Janis Joplin; the fourth, ‘Monsters’, is about the artist Hannah Wilke, whose former lover Claes Oldenburg demanded that his name be removed from her published writings: ‘Eraser, Erase-her – the title of one of Wilke’s later works.’

It seemed clear to me, when I was reading, that Kraus’s background was in art and film, not writing. Her ideas have that hit-and-miss boldness I associate with downtown word-based artists – Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer, Patti Smith. Parts of all the letters are brave and interesting, but other parts made me feel the way Semiotext(e) used to in its heyday – maybe I’m just not cool enough to get it, but isn’t some of this stuff a bit unpleasant? The Harbury letter in particular seems to be aiming for something quite ambitious: ‘Since Guatemala is so small and all the facets of its history can be studied, it’s a paradigm for many Third World countries. If we understand what happened there, we can get a sense of everything.’ She’s trying, I think, to link Harbury and her husband in Guatemala and herself and Dick in Antelope Valley. Something to do with how ‘for months I thought this story would be something about how love can change the world’? She does something similar a bit later with a neighbour in Thurman, ‘Renee Mosher, an artist-carpenter-tattooist’ whose house ‘is getting repossessed next month’. Chris has a dream, she writes, in which she and Renee are best friends, although in waking life, that would be an ‘impossibility’ because ‘there is a culture of poverty and it’s not bridgeable.’ Am I right to suspect that Kraus is getting flustered here?

Renee Mosher is succeeded by an acid trip – ‘nice in a California kind of way’ – and a long wig-out about schizophrenia, one of the 1980s Semiotext(e)’s favourite topics, and, Kraus says, ‘a state that I’ve been drawn to like a faghag since age 16’. ‘Schizophrenia is metaphysics-brut,’ she muses at one point. Then: ‘the world gets creamy, like a library.’ Also, ‘My entire existential-economic situation was schizophrenic, if you accept Félix’s terms.’ So she smokes some pot and flashes back to her youth in New Zealand; then, back in LA in April, she has what she calls ‘a perfect afternoon’ with Dick. And that’s pretty much that for Dick and the Dick crush, until September, when Chris gets Sylvère to intercede again and Dick, at long last, replies.

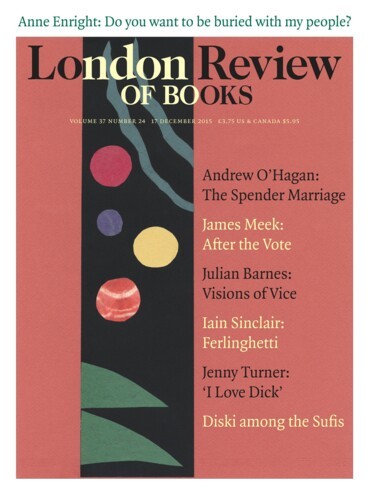

Is Emily Gould right, then, that this is the most important book about men and women written in the past century? I stared hard at the book while I thought. The cover is plain green with the title huge in eye-test capitals, the word ‘LOVE’ done in a sore-looking penis pink, and I remembered pop singles from the punk and post-punk period, when song and band and title and cover all worked together to make what, if you were lucky, would be seen as an instant classic. When this happened, it didn’t matter that the words and ideas were blunt and basic, because the whole amounted to something bigger. And then, when it found its audience, the response made it bigger still.

I know that singles haven’t been like this for generations, and I agree that it’s a strange sort of instant classic that takes more than a decade to find its fans; but this is the best way I can find to acknowledge this book’s huge charisma while also admitting that it didn’t really work for me. ‘When the form’s in place, everything within it can be pure feeling,’ Kraus writes of Schoenberg at one point, fully aware, I’d imagine, that her own work too has this self-reflexive neatness. Kraus has also said how much she hates ‘hetero-male … Story of Me’ novels in which ‘everything else’ becomes ‘merely a backdrop to the teller’s personal development’. And yet, her own book is driven exactly by ‘the teller’s personal development’, from frustrated wife to spurned lover to independent woman artist. Beneath the posing and the psychodrama, I Love Dick is an instant-classic feminist Künstlerroman.

Gould also likes Kraus’s book because it starkly depicts what she calls ‘the problem of heterosexuality’: that if you’re a woman and want to share your life with men, you have to recognise the millennia of patriarchy that continue to skew the relation in all sorts of ways, from obviously atrocious to ungraspably subtle. This is absolutely true and fair. Over the course of her novel, Kraus portrays herself patronised, blanked, belittled, ignored, pathologised, passed over, ripped off, underestimated, messed about, sexually exploited, traded like chattel between her husband and a work contact, each man more eager to keep in with the other man than bothered about her: none of the behaviour she describes is in any way illegal, and most of it isn’t at all unusual. Kraus is also right about what can happen to women when they put the situation down in writing. ‘Bitches, libellers, pornographers and amateurs’ are only some of the names used. ‘Why does everybody think that women are debasing themselves when we expose the conditions of our debasement?’ Kraus asks later. ‘Why do women always have to come off clean?’

Kraus is especially good on sexual shame and self-abasement, the uniquely intolerable torment when you offer yourself and aren’t wanted; or, as Kraus more epigrammatically puts it, ‘shame is what you feel after being fucked on quaaludes by some artworld cohort who’ll pretend it never happened, shame is what you feel after giving blowjobs in the bathroom at Max’s Kansas City because Liza Martin wants free coke.’ Shame is always difficult to write about because of the way it has of leaking out, soaking and spoiling everything around it; but Kraus’s high-pop pointillism is good at both acknowledging this commonality and keeping it contained. One nice thing about the 21st century so far is watching feminine abjection get funnier and funnier, in Girls and Bridesmaids and so on: a world in which you can make comic gold from sex with a stringy sous-chef in a metal pipe has the makings of becoming a better world for us all. I Love Dick, surely, stands Harold Bloom-like behind that sous-chef, whether writers are consciously aware of it or not.

It’s interesting to consider how the internet fits in with all this – in its commercial infancy when I Love Dick was first published and not mentioned at all in the actual novel (strange, given that its protagonists are so avant-garde). The internet, as Gould wrote, certainly does enable ‘hordes of frightened, anonymous men to try to silence women via harassment and shaming’, but it also gives women the wherewithal to find one another and form their own horde, as Gould acknowledged, ‘on a grander scale … than before’. ‘The click of recognition’ is what the Women’s Liberation Movement used to call that moment when you first recognise that your problem is not yours alone and not of your own making. That click now also activates all the data that back this up.

So, yes, it’s true that shaming is predominantly something that men do – or try to do – to women. And yet it’s also possible for individual men to be shamed as well, and let’s be honest about it, Kraus’s book would not be so powerful and entertaining if Dick were not an actual person, as capable as any woman of getting hurt. ‘I think of our story as performative philosophy,’ Kraus writes at one point and she’s right. The entire book is a gigantic speech-act, and not a kind one, revealing the common love-rat in all his pink-skinned pathos. Perhaps one day Dick will publish some sort of Birthday Letters project, letting us know what this has felt like.

Kraus did try, she has said, to hide the Dick in her book as much as possible. When she pretends to cite and quote his writing, for example, she substitutes titles and writing of her own. In the novel, we see her wondering whether to change Dick’s name to ‘Derek Rafferty’, although we know she will decide against it. And in terms of ‘performative philosophy’ there’s no doubt she makes the right decision: men have been writing about female muses for centuries, without much comeback or complaint. Aesthetically too, I think we’d agree that Kraus stuck with the better title (I Love Derek?). But in terms of balancing such considerations with the ethical … ‘Who gets to speak and why is the only question,’ Kraus writes anthemically at one point. I think she’s wrong in this. It’s not.

I don’t suppose the real-life Dick necessarily appreciates it, but Kraus’s tone throughout the book is affectionate, respectful, protective even (‘On the phone I was ashamed. My will had ridden all over your wishes, your fragility. By loving you this way I’d violated all your boundaries, hurt you’). I found myself thinking about a splendid rare-breed pig that most certainly does end up getting eaten, but only after a lovely life and luxury slaughter, and is bade farewell at table, perhaps, with a little speech. Thank you Dick, for being called Dick, so my book gains power from the touch of your Dick-like presence and phallic title. Thank you Dick, for serving yourself up to me so I could change my life.

No such warmth is shown to the novel’s minor antagonists, the ‘deadbeat’ tenants who ‘trashed’ the Thurman house before Sylvère and Chris got them evicted: ‘When it was all over and we won, we both agreed we couldn’t care less about material possessions. We were just sick of being had.’ A taxi driver rants ‘about wogs and how reading William Burroughs made him different from all the other cab drivers in Columbus and could I tell him how to make a living as an artist?’ Is it self-evident to everybody why people (e.g. ‘artworld cohorts’) are wrong to be rude to Chris, but it’s fine for people (i.e. Chris) to be rude about tenants and taxi drivers?

I must be nearer in age to Kraus than to her new admirers. I own a copy of Semiotext(e) from the 1980s. I read Dick Hebdige’s early work soon after it came out and remember it so fondly that I intend to look at it all again. And I often feel bad about the way my generation seems to have grabbed all the houses, so I’m surprised Kraus’s fans aren’t as intrigued as I am by her interest in real estate. Might some of them also be her tenants? Have some of them decided the only way they’ll ever get money is by becoming landlords too? In her interview with Sheila Heti, Kraus said that she operates her investments as ‘lower-income, affordable housing’ and recommended landlording as ‘a way of engaging with a population completely outside the culture industry. Kind of like in gay culture, where hookups are a way of escaping your class.’ Young artists, she said, should try to do something similar, ‘because what’s going to happen in the next five years if you stay within your niche is already so circumscribed and predictable. And what can happen if you leave it is unknown, and therefore bigger.’ Heti asked for advice for those who might want to follow her example. ‘I think there are entrepreneurial opportunities everywhere, always.’ If she was starting out again, Kraus added, she’d probably buy in Detroit.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.