10 March. At 6:45 a.m. I set off by car service to Newark airport to catch the 10 a.m. Virgin/Continental flight to Gatwick. At this time of the morning the New Jersey Turnpike is too busy altogether. This use of altogether, I’m reminded by Terence Patrick Dolan in A Dictionary of Hiberno-English, means ‘wholly, completely’ and may be compared to the Irish phrase ar fad, particularly in its positioning at the end of a sentence.* There’s a world of difference between the phrase ‘you’re altogether too thin-skinned’ and ‘you’re too thin-skinned altogether.’ The latter, Dolan notes, is spoken by Seumas in Act 1, line 87 of Sean O’Casey’s The Shadow of a Gunman. ‘The main intention of this dictionary,’ I’m only after reading in the introduction (only after is another Gaelic construction), ‘is to make accessible the common word stock of Hiberno-English in both its present and past forms, oral and literary ... Much of the vocabulary of Hiberno-English consists of words in common currency in Standard English, but an appreciable proportion of the word stock of Irish people is not standard and may be misunderstood, or not understood at all, by speakers of standard or near-standard English.’ I’m thinking of how I’m a cute hoor altogether – a phrase that might certainly be misunderstood – for having changed from tonight’s 9:25 Virgin flight with its 9:05 a.m. arrival into Heathrow to this much less damaging daytime jaunt. When I look up cute hoor, I’m directed to hoor and read as follows:

HE version of ‘whore’ hore. The pronunciation/hu[e]r/ was common in England in the 16th and 17th centuries and lasted into the 19th century. Hiberno-English retains this older pronunciation, while the meaning has become extended from ‘prostitute’ to refer to any person, male or female, who is corrupt; and it may be used affectionately as well as pejoratively, especially when qualified by the adjective ‘cute’– ‘That man’s such a cute hoor he’d build a nest in your ear.’

Dolan expands on the use of the word hoor with a range of examples from the writings of Patrick Kavanagh, Brian Friel, Tim Pat Coogan, Oliver St John Gogarty, Neil Jordan and Hugh Leonard. It’s a method that seems to be at once academically sound and, for those committed to a long weekend in England and Wales carrying only one bag and one book, perfect for a bit of one-way crack, or ‘entertaining conversation. Ir craic is the ModE loanword crack < ME crak, loud conversation, bragging talk; recently reintroduced into HE (usually in its Ir spelling) in the belief that it means high-spirited entertainment.’

I’ve taken this matter of the one bag as further proof of my cute hoordom, since I’m determined to hand over luggage to an airline only when absolutely necessary. When I arrive at Newark, I check in and go to the gate. Then I have a thought only a cute hoor would have. I’d originally booked a premium economy ticket for tonight’s flight. When I changed my ticket, they reminded me that Continental has no such class on this flight, though I’ll avail of it on the Virgin flight back. Maybe they’ll reimburse me the difference? I go back to the desk and explain the situation and am delighted to be bumped up from economy to first class. The bad news is that the flight is running two hours late. There’s the usual plamas over the reasons. I’m using plamas less in the generally accepted sense of ‘flattery, empty praise, cajolery’ than that given by Dolan in his definition of a plamasai as ‘a soft soap merchant’. I notice, with a smidgeon of alarm, that Dolan doesn’t attempt an etymology. I myself have always been taken by the idea that plamas is a corruption of ‘blancmange’, an etymology bolstered by Patrick Dinneen’s translation, in his dictionary, of plamas as ‘flummery’, itself defined by the OED as ‘a name given to various sweet dishes made with milk, flour, eggs etc’. By the time I get into Gatwick, it’s 11:30 p.m., and so flaithiuil, or ‘generous’, have the attendants been that I’ve had one too many jorums of Bailey’s Irish Cream, itself a flummery beyond compare, the flummery itself. I take a cab from Gatwick to London driven by a young Indian man who’s about to have an arranged marriage. The Gaelic term for an ‘arranged marriage’ is cleamhnas, and people who’ve had arranged marriages, or are merely related by marriage, are known as clownies, an idea I’m still pondering as I duck-walk into the famous Groucho Club.

11 March. After a lie-in and lunch at Alastair Little’s fine establishment, I go by train to Oxford. The hawthorn hedges are blooming already, and I’m struck by the extraordinarily high number of fairy forts en route. A fairy fort is, as I recall from Dolan, ‘a smallish semi-circle of trees regarded as unlucky to dislodge, actually the site of an Iron Age enclosure’. I thought the English were more hard-headed than this, that it was the superstitious Irish who didn’t dislodge fairy forts for fear of reprisals from the gentle folk, a term not included by Dolan, though it does appear in the 1996 Concise Ulster Dictionary edited by C.I. Macafee, which makes much of the relationship between ‘gende’ and ‘gentry’. The English and Irish are much closer, of course, than anyone lets on. As it happens, I’m in Oxford for just a few hours to read poems to the English and Irish Societies, who have joined forces for this occasion. The fact that they are in cahoots doesn’t imply that they’re up to any shenanigans. Dolan quotes McCrum, Cran and MacNeil’s entry in The Story of English on the word: meaning ‘mischievous behaviour, trickery’ it ‘is first recorded in America in 1855 and comes from the Irish sionnachuighim, meaning “I play the fox, I play tricks.” Or does it? One authority believes the word to be American Indian. Another folk etymology gives a contraction of the Irish names, Sean Hannigan.’ This musing by McCrum, Cran and MacNeil is all very fine and well in the context of the book of a television series. It seems odd, however, in the context of a scholarly volume, that the validity of the etymology is neither supported nor dismissed, while no comment is made on the American Indian source.

I’m a little worried about being back in Oxford only a few months after giving the Clarendon Lectures and reading at Blackwell’s. But I’ve been assured that I won’t be overstaying my welcome – held by the Irish to be one of the worst offences of which anyone is capable – by my dear friend Tom Paulin. Coincidentally, Tom Paulin has written a little introduction to the Dolan book in which he remembers how ‘as the political crisis in the North lengthened, I began to feel the need for a dictionary which would gather innumerable local words from all parts of Ireland together – a hospitable inclusive text which, without triumphalism, would be a national dictionary. This Dictionary of Hiberno-English answers that need.’ I fear that Tom Paulin may be over-enthusiastic here, but it’s always difficult to suppress his enthusiasm, to smoor him as one might a fire. He himself is listed under the entry for smoor, ‘to suffocate, to suppress’, in a quotation from Seize the Fire. Paulin’s title, with its nods in the direction of Blake’s ‘The Tyger’ and Horace’s ‘carpe diem’, might also send a reader in the direction of ‘Lillibullero’, the Williamite song in which the phrase bullen an la is generally accepted to be a variant on the phrase bainim an la, with its suggestion of ‘carrying the day’. Dolan’s brief entry on lillibullero refers to it being a ‘refrain (probably intending to represent Irish sounds)’. This ‘probably intending to represent Irish sounds’ is, once again, a tad strange in the context of a volume that purports to be A Dictionary of Hiberno-English, a volume that includes without preamble vast numbers of Gaelic words and phrases, many of them scarcely in common currency. On one page chosen at random I see ciseog ‘a pair of baskets across a donkey’s back’, ciste ‘a present of money’, ciumhais ‘an edge’, ciunas ‘quiet’, clabach ‘garrulous’ and clabar ‘mud’. Amazingly, the most common spelling of the Hiberno-English version of clabar – ‘clabber’ – is not given at all, though it does show up in the related bonnyclabber, ‘thick milk that could be used for churning’. There is, however, no cross-reference between the two words. This same page chosen at random gives us the word citeog, with a pointer in the direction of ciotog, ‘the left hand, a left-handed person’. While Dolan cites Joyce’s use, in Finnegans Wake, of kithoguishly, he nowhere mentions the most common Hiberno-English version of kitter-fisted or kitter-pawed. It’s the sort of thing that gives one a quare gunk, or takes one aback, or surprises one. Once more, I notice there’s no attempt to offer an etymology of this word gunk or gonk, which I take to be a straight borrowing from the Donegal pronunciation of the phrase agamharc, ‘seeing, looking, having a vision’. I mull this over as I stare into the groodles or ‘bits at the bottom of a soup bowl’ in that Thai place on Oxford’s main drag, then take a train back to London.

12 March. I make my way over to Gresham College – ‘the oldest college in London’, as it’s billed – for a conference on ‘Sensing the Poem’. ‘The aim,’ the flyer reads, ‘is to create an intensive one-day environment in which readers, poets, speakers of poetry, and critics engage with the perceived nature of much contemporary poetry: while readers may think it impenetrable or obscure, and critics may respond to it in intimidating literary or analytical terms, poets may have entirely different ideas about their work’s objectives and accessibility.’ Though I’m somewhat wary of helping make snowballs for people to throw at me, particularly in a climate in which the ‘No Brain’ school of criticism seems to reign, I’m quite looking forward to an argy-bargy with Neil Corcoran, with (or against) whom I’m billed to appear. Indeed, I fully expect to end up in some class of a donnybrook before the day is over. A donnybrook is ‘a riotous assembly, free for all <Donnybrook, a village near Dublin, now a respectable suburb, site of an uproarious week-long fair dating from at least the 13th century, discontinued in the middle of the 19th century’. A donnybrook, a barney, a trasby. The general difficulty facing the etymologist of Hiberno-English may be seen in these last two words, not included by Dolan, but given by Loreto Todd, in Words Apart: A Dictionary of Northern Ireland English (1990), as terms for a ‘row or debate’, supposedly from barnghlaodh, ‘a battle-shout’ or a ‘row, misunderstanding’, supposedly from trasnuighim, ‘to contradict, forbid, oppose’. C.I. Macafee’s Concise Ulster Dictionary gives barney as English slang for an ‘argument’, though does not bother its barney at an attempt at an etymology. It does bother its barney to give a very fetching portrait, though, of an ass and its accoutrements, or bardhings, including its bardock, finag, kishogue or creel, its braighum or back-suggan, its graith, straddle or strar and, of course, its carrafufflies. ‘the hinged bottoms of donkey creels’. Now, Dolan’s donkey wouldn’t be quite so well turned out as Macafee’s, since Dolan doesn’t provide carrafufflies, strar, straddle, graith, braighum, finag or bardhings. We do, however, get kishogue (remember ciseog?), creel, sugan (‘a rope made by twisting straw or hay’) and bardog or pardog, a ‘pannier’, the bar or par elements being versions of the aforementioned barr meaning ‘head, or top’. A barney is a set-to of heads, I expect, though there’s always likely to be some theory that’ll put the kibosh on that one.

Two images come to mind. One is of a dealership sticker from McDiarmuid’s of Barrhead – Barrhead – where Michael Longley used to buy his motoring cars, which was stuck in the rear window of each in turn. The second is of those lines of Longley’s from ‘In Memoriam’, ‘Your nineteen years uncertain if and why/Belgium put the kibosh on the Kaiser.’ This allusion to the First World War song surely provides the most memorable use of the phrase in recent Irish writing, worthy of a place beside the sentence from Edna O’Brien’s A Pagan Place used here to illustrate kibosh. Dolan, as this example indicates, seems not to be very interested in word usages by poets, other than those included in the hurried-looking selection by Declan Kiberd in the Field Day Anthology of Irish Literature. He or his correspondents don’t seem even to have read much Seamus Heaney after 1990, so miss, for example, his use of the word trig in ‘The Schoolbag’ (collected in Seeing Things, 1991), a poem dedicated to another champion of local Irish dialect, John Hewitt. So far as I can see, Hewitt isn’t quoted by Dolan. He’s certainly not listed among the literary sources, though that doesn’t necessarily mean he’s not included somewhere in the body of the text, since I myself appear at least twice, by way of examples of the use of the terms mooley, meaning ‘a hornless cow’, and your man, meaning ‘any specific individual’, though I’m not formally listed. This kind of inconsistency is now beginning to seem consistent.

In any event, your man Corcoran and I slabber on until lunch time on the subject of what poems mean, rather than what poets think they mean. I’m using slabber in the sense of ‘talking too much’ rather than the sense of ‘one who works with slabs of stone’, though I recall how Ciaran Carson used to have a clipping of a newspaper ad that read ‘Fireside Slabber’ taped to his mantelpiece. That the word slabber is itself not included sends up another little alarm, suggesting that Dolan’s enterprise is somewhat less than trig, meaning ‘reliable, neat’, and more like its next-door neighbour, trina cheile, ‘mixed up, in disorder’. This, I’m afraid, also turns out to be the case with this little conference, despite having some wonderful people in attendance. By the end of the afternoon, some class of modest kibosh has been put on the proceedings. ‘Various claims have been made for its origin,’ Dolan writes of kybosh or kibosh, ‘including Yiddish, Anglo-Hebraic, Turkish and Irish, with kybosh sometimes regarded as a re-formation of caidhp and bhais or caidhpin an bhais, “cap of death”, the black cap or judgment cap worn by judges when pronouncing sentence of death’.

As Neil Corcoran and I are making a few pronouncements on this, that and the other over a quick bite of dinner in the Groucho, we run into Sean Rafferty, a broadcaster with whom I worked from time to time while I was in Belfast. Now based in London, Sean is a wonderfully engaging character who, year after dreary year, presented Scene around Six, BBC Northern Ireland’s nightly news and current affairs programme, interviewing Ian Paisley and other fireside slabbers (I should probably write ‘slabberers’), both Unionist and Nationalist, Protestant and Catholic. I get another quare gunk when I notice that Dolan sees fit to include unionist but not nationalist, Twenty-Six Counties but not Six Counties, protestant but not catholic, though he does find room for entries on the Children of Mary, Holy Communion, the Stations of the Cross and the Society of St Vincent de Paul and innumerable other references to Roman Catholicism. The entire undertaking begins to be very far from Protestant-looking.

13 March. Most of the morning is spent on the train from Euston to Bangor. As I pass through ‘Sunny Prestatyn’, I can’t help but think of those lines of Larkin in his poem of that title, as he describes the defacement of a hoarding poster:

Huge tits and a fissured crotch

Were scored well in, and the space

Between her legs held scrawls

That set her fairly astride

A tuberous cock and balls

Autographed Titch Thomas, while

Someone had used a knife

or something to stab right through

The moustached lips of her smile.

I’m looking forward to a presentation of barddoniaeth erotig, or ‘erotic poetry’, scheduled for 2:30 this afternoon in the Ty Newydd festival, in which I’m reading later on in a programme entitled ‘The Big Night’ with Simon Armitage, Robert Minhinnick and Sheenagh Pugh. There’s not much awareness of the erotic in Dolan’s Dictionary of Hiberno-English, I’m afraid, though he includes flah ‘(to engage in) sexual intercourse’. There’s no mention, in the etymology of such words as bodach or bodachan, ‘an unintelligent person; an upstart, a churl’, of the root of the word, bod being a term for ‘penis’. There’s some connection, so, between the swelling bud and the swelling bod in ‘tuberous cock and balls’, a connection made all the more intriguing by the fact that the poem immediately preceding ‘Sunny Prestatyn’ in The Whitsun Weddings is ‘The Importance of Elsewhere’, with its autobiographical

Lonely in Ireland, since it was not home,

Strangeness made sense. The salt rebuff of speech,

Insisting so on difference, made me welcome:

Once that was recognised, we were in touch.

That ‘touch’ in ‘The Importance of Elsewhere’ is picked up in the dialect name ‘Titch Thomas’, the toucher of all touchers, and is a measure of the centrality to both poems of the notion of language and landscape and body being one. Sadly, the Barddoniaeth Erotig is cancelled for reasons that aren’t entirely clear, so I take a dander, ‘a leisurely stroll’, through the village of Cricieth, stopping in the village pub for fish and chips – or ‘one and one’, as it’s known in Dublin. I’m reminded of a dish my father used to tell me about, known as ‘potatoes and point’. Griffin describes it in The Collegians: ‘when there’s dry piatez’ – potatoes – ‘on the table, and enough of hungry people about it, and te family would have, may be, only one bit o’ bacon hanging up above their heads, they’d peel a piatie first, and then they’d point it up at the bacon, and they’d fancy that it would have the taste o’ the mait when they’d be aitin’ it after.’ I pass up the chance to eat a little flummery for dessert, reminding myself that Dolan quotes Onions (The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology) and gives flummery as a version of the Welsh word llymru, though he doesn’t specify what llymru means, allowing us to assume that it signifies ‘a kind of porridge’. At 4 p.m. I catch a whileen – ‘a little while’, of course – with two Welsh-language poets, Gerallt Lloyd Owen and Dic Jones, who read their poems in the Lloyd George Museum down the street, though I haven’t the faintest idea what they’re talking about any more than, later that night, I understand the mysteries of Y Slam Gymraeg, billed as the first ever Welsh poetry slam.

Over the course of the evening, it becomes clear to me that there’s a deep and divisive rift between Welsh and English-speaking Welsh poets that is quite absent in Ireland, where there’s much kiffling back an’ forrit between the two. (I’m alluding here to the great poem ‘Me and Me Da’ by W.F. Marshall, a poet and the author of an Ulster dialect dictionary which, according to J.A. Todd, in the introduction to his Livin’ in Drumlister: The Collected Ballads and Verses of W.F. Marshall, ‘was irretrievably mauled by his Golden Retriever pup’. The fate of that manuscript doesn’t warrant Marshall’s absence here among sources literary or learned.) Another Irish poet whose kiffled over here for a few days, whom I run into later in the bar of the George Hotel, is Cathal O’Searcaigh. Cathal O’Searcaigh lives in Gortahork and writes in Gaelic about, among other things, his being gay, in one wonderfully frank hymn to the beauty of na buachailli bana, or ‘white boys’. These ‘white boys’ are not to be confused, by the way, with the Whiteboys. Dolan describes them in an entry as ‘a widespread secret society developed in the 1760s in Co. Tipperary and north Co. Waterford’. Though he mentions other agrarian secret societies in a note, he does not include entries on Rightboys, Threshers or Peep o’Day Boys.

14 March. Up shortly after peep o’ day, I take the air. It’s a beautiful sunny morning, the forsythia almost exactly the same colour as the yellow line on the side of the road in Britain or Ireland, exactly the same colour as the line down the middle of the road in the US. I’m reminded of the yarn about what a single yellow line means – no parking at all. A double yellow line? No parking at all at all. This corresponds to the Gaelic phrase ar bith, or ar chor ar bith, a phrase so common it’s astonishing that Dolan doesn’t include it where one would expect it in so many Gaelic entries. He does give it, however, under at all, an adverbial phrase ‘expressing assertion’. I head up to Ty Newydd, Lloyd George’s last home, now a writing centre, for a music and poetry event with Cathal O’Searcaigh and the cellist Neil Martin. Cathal O’Searcaigh reads a poem in which he compares the Irish landscape to a male body – or is it a male body to the Irish language? It all comes back to me as I lurch past the sign for ‘Sunny Prestatyn’ later that afternoon, that image in Larkin of ‘the hunk of coast’. I get into London just in time to make my way over to the Ivy for dinner with my friend, the poet Alan Jenkins, before repairing to the Groucho to discuss life, love and literature into the wee small hours, then pack in readiness for my flight back tomorrow. It’s been a night for people-watching. The great Icelandic singer Björk, whom I’ve admired since her Sugarcubes days, was briefly in the Groucho. Three tables away in the Ivy was Monica Lewinsky, she of that most famous of monikers. A ‘moniker’, by the way, is a Shelta word, a variant of munnik, itself backslang deriving from the Gaelic word ainm, ‘a name’. As a last word, as it were, I’ll note how I’m sent by Dolan, in his note on Shelta, ‘the secret language of Hiberno-English formerly spoken by members of the travelling community’ to ‘see Cant; Gammon’. These are, of course, the terms used by travellers for their own language. I look up Cant. It, too, directs me to Gammon. Unfortunately, there is no entry for Gammon, yet another aspect of this Dictionary that not only gives me a quare gunk, but at which I take a scunner.

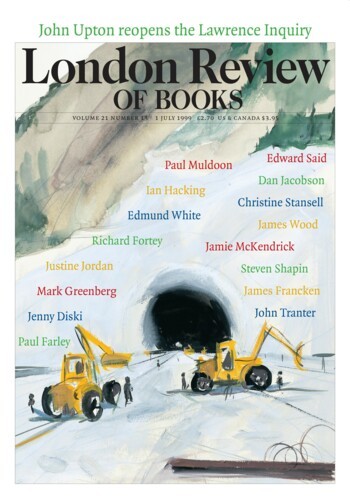

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.