The fire at Grenfell Tower on 14 June 2017 killed 72 people, 18 of them children. Most died from asphyxiation after inhaling toxic smoke from the cladding on the block, which acted like a coat of petrol on the walls. Some died leaping from the building. Families died together, huddled under beds, having been told to stay where they were. Disabled residents died waiting for a rescue that never came. Every death was avoidable. Every death was the result of choices – acts of negligence, carelessness, contempt, incompetence and deliberate deceit – made by individuals, corporations and elected officials. The residents had the right to expect their landlord, in this case a subsidiary of local government, to ensure their homes were safe. They had the right to expect their government to enforce safety rules and to identify and combat fraud and malpractice by suppliers and fitters. Instead, those in power at every level abdicated their responsibilities.

‘Grenfell is a lens to see how we are governed,’ Stephanie Barwise, one of the lawyers for the bereaved, told the second part of the Grenfell Tower Inquiry, which (among other things) dealt with the actions of elected officials. The inquiry’s final report, issued on 4 September, cuts a critical swathe across public and private bodies. It is a sober and dispassionate document – its authors are all too aware that it will form the basis for future prosecutions – and its restraint seems at times too mild a response to the arrogance and incompetence displayed in the evidence. It is now indisputable that companies rigged safety tests with the complicity of the testing authorities, that politicians refused to act on safety concerns because to do so might have obstructed deregulation, that a social landlord which loathed its tenants ignored and concealed fire safety notices. The report firmly establishes the fire as the shameful ‘culmination of decades of failure’.

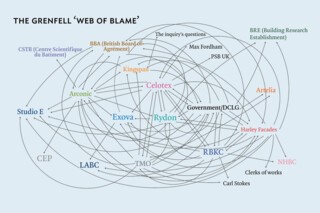

In his closing statement, Richard Millett, lead counsel for the inquiry – responsible for examining all the witnesses and ensuring its terms of reference were addressed – presented a ‘spider’s web of blame’: the image showed a tangle of arrows going between Kensington and Chelsea Council, testing bodies, architects, manufacturers and construction companies. It’s almost impossible to decipher, and that was his point: each arrow represented one party’s attempt to shift responsibility to another and back again – a sorry repetition of the ‘merry-go-round of buck-passing’ that Millett argued had characterised the first phase of the inquiry. In countries with sophisticated regulatory regimes, catastrophes such as Grenfell ought to be impossible: when they occur they are invariably multi-causal, the result of many overlapping failures. This complexity is often taken to be exculpatory and used by guilty parties to muddy the issue of responsibility. Lawyers for the bereaved asked the inquiry not to get entangled in this web, but instead to begin to apportion the degree of responsibility borne by the various parties. The final report assigns ‘considerable’ or ‘very significant’ responsibility for the fire to the contractors and subcontractors who executed the refurbishment.

The first phase of the inquiry, which reported in October 2019, was concerned with establishing what happened on the night of the fire: how it started, how it engulfed the building, and the response of the London Fire Brigade (LFB). It established what is now a familiar story. During a council-commissioned refurbishment between 2012 and 2016, Grenfell Tower was fitted with unsafe, flammable cladding and combustible insulation. An ordinary appliance fire on the fourth floor moved through a window frame and lit this outer skin. Toxic smoke rapidly filled the building. The first phase report acknowledged the heroism of individual firefighters, while sharply criticising the LFB’s failure to abandon its ‘stay put’ advice or to prepare contingency plans for situations in which that strategy might fail. Many of those who died would have survived had it been abandoned earlier.

The testimony provided by firefighters at the scene made clear that nobody at Grenfell that evening understood what kind of fire they were seeing, or had been trained for it. Later evidence revealed that Arconic, the cladding manufacturer, had been told a decade before the fire that fitting a large tower block with polyethylene-core panels would be equivalent to attaching a 19,000-litre oil tanker to the outside of the building. The potentially lethal consequences were perfectly clear to Arconic’s senior management. ‘What will happen if only one building made out [of] PE core is on fire and will kill sixty to seventy persons,’ one manager asked in an internal memo, ‘what is the responsibility of the ACM [aluminium composite panel] supplier?’

The second phase of the inquiry had the more expansive task of establishing how, ‘in 21st-century London … a reinforced concrete building, itself structurally impervious to fire’, could be ‘turned into a death trap that would enable fire to sweep through it in an uncontrollable way in a matter of a few hours’. The evidence uncovered in pursuing that question has received less press attention than it should have. Public inquiries cannot determine civil or criminal liability, but the report makes devastating criticisms of every public and private body involved with the tower and its refurbishment. At a national level, politicians from multiple governments (Labour, Conservative, the Liberal Democrat-Conservative coalition) and civil servants failed to act on fire safety and regulation. (Two former prime ministers – Blair and Cameron – have already tried to spin their way out of criticism.) Kensington and Chelsea’s cost-cutting council and its Tenant Management Organisation (TMO) bore direct responsibility at a local level for the tower’s management and its refurbishment. Three manufacturers – Arconic, Kingspan and Celotex – were responsible for the combustible products used in its refurbishment. These products were either brought to market when they shouldn’t have been or were misleadingly certified by the Building Research Establishment (BRE) and the British Board of Agrément (BBA). The architects, Studio E, and their fire safety consultants, Exova, failed to produce a fire safety plan beyond a preliminary draft. Rydon, the project’s main contractor, and Harley Facades, its cladding subcontractor, neglected their responsibilities, failing to check the safety of the products they installed or to demand a completed fire safety strategy. Both used inexperienced, incompetent or complacent teams; Rydon’s primary concern was cost-cutting.

These parties can be divided into those that were malign through intention and those that were malign through incompetence, with some falling into both categories. Incompetence is not a lesser category where safety is concerned, especially when knowingly indulged. The most damning evidence presented to the inquiry often came from direct testimony or contemporaneous emails, but some chilling moments were provided by far-sighted, unheeded experts. The report’s first volume (of seven) quotes H.L. Malhotra, a scientist at the Fire Research Station (a precursor to the BRE), in 1986: ‘The burden of responsibility is being shifted from the central or the local authorities to the individual or corporate designer/contractor for the adequacy of his system … It will be perhaps another two or three decades before the consequence of this approach can be seen.’

Theresa May, prime minister at the time of the fire, announced the inquiry on 15 June, the day after the disaster, and accepted without quarrel the terms that Martin Moore-Bick, the retired appellate judge chosen as chair, proposed. In a letter to May in August 2017, Moore-Bick noted that some of those affected thought the inquiry’s scope ‘should include social housing policy’ more generally, as well as covering the local authority, the TMO and their actions in the aftermath. He demurred at the time from addressing ‘broad questions’ of a ‘social, economic and political nature’, preferring to consider the precise events of the night and the conditions that gave rise to the fire. In fact, apart from housing policy, these wider questions bear heavily on the final report. How could they not?

Some survivors, especially those represented by the solicitor Imran Khan (who also represented the family of Stephen Lawrence), persistently raised the question of institutional racism and discrimination. More than three-quarters of the tower’s residents were non-white. The issue surfaces, somewhat defensively, in Moore-Bick’s preface. Although such considerations were outside the inquiry’s terms, he notes that he found some evidence of prejudice in the response to the fire, but no evidence that homes were deliberately allocated ‘to those of non-white ethnicity in a building known to be dangerous’. Nor did he uncover evidence that decisions to cut corners or to delay remedial safety work were motivated by racial or social prejudice. Yet the contempt with which the TMO treated its residents – its ‘serious failure … to observe its basic responsibilities’ – is difficult to explain other than as a diffuse consequence of class superiority and callousness. The attitude was endemic: the transcripts of the hearing show the councillors charged with scrutiny of the tower’s refurbishment dismissing complainants as lacking gratitude for a ‘£100k gift from the state’.

Statutory inquiries have become an increasingly common means of addressing scandals and crises in Britain. Some have resulted in serious and enduring change: the regime of DBS checks for child safety is a direct result of the Bichard inquiry into the Soham murders. Others, such as the post-Savile Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse and the ongoing Undercover Policing Inquiry, have failed to find answers and lost the trust of the groups they were supposed to serve. The Grenfell Tower Inquiry has been one of the most complex and expensive ever undertaken, costing £200 million (including legal expenses) and involving 638 core participants, the disclosure of 320,461 documents and hundreds of hours of testimony and cross-examination conducted over seven years – a period extended by the pandemic but not unusual among contemporary inquiries. The 1700-page report on the second phase seems relatively concise.

Questions about scope, duration and cost follow in the wake of public inquiries. Politicians might initiate an inquiry to establish the facts about an event, and to determine how it can be avoided in future, but they are also convenient means of removing the issue from public debate (‘we must wait for the inquiry to report’ deserves a spot in ministerial bingo). Recommendations resulting from inquiries invariably have costs and consequences for politicians, and because of this are often ignored. Boris Johnson loudly accepted the recommendations of the first phase of the Grenfell inquiry, then quietly buried many of them.

At its inception, many families feared that the inquiry would be a drawn-out establishment whitewash, or that it would spread the blame so wide that nobody would be held accountable. Neither has proved the case. A third anxiety, that time would dull the public’s appetite for justice, is harder to allay. It takes an effort to recall the anger so widely felt the morning after the fire, when the burning tower seemed to represent so much that was wrong with Britain’s social and political order, its private affluence and public squalor, the avarice and arrogance of its ruling elite. Left-wing MPs were castigated for saying what happened was ‘social murder’ or calling on Britain to ‘burn neoliberalism, not people,’ but the final report confirms the soundness of those early intuitions. In 2017, only the most optimistic would have believed that the catastrophe would lead directly to substantive political change; but even the most pessimistic would not have predicted that, seven years on, almost nothing would have changed. Survivors fear that the public is easily inured to disaster, as those responsible retire on healthy pensions or are elevated to the peerage, and it has certainly seemed true that the media lose interest all too quickly.

The story established by the inquiry is shocking in its detail but unsurprising in its general shape, and perhaps this helps explain the rapid decline in press interest: the detailed early accounts have been succeeded by indifferent silence. Grenfell happened because many British institutions have been progressively hollowed out, including the press. The kind of local journalism that might have uncovered and campaigned against the problems at Grenfell – many residents had sought again and again to have them redressed – is long dead; few papers, at city or national level, could afford regular reporting on the inquiry or the fire’s causes and aftermath. Two journalists have been essential: Peter Apps of Inside Housing has reported exhaustively on all aspects of the case as well as examining the findings on his Substack and in his book, Show Me the Bodies (2022). At the BBC, Kate Lamble produced a detailed weekly podcast throughout the hearings, though its insights rarely seemed to make it across to the corporation’s main news programmes. In an act of managerial malfeasance typical of the BBC, Lamble was made redundant a day or two after the inquiry reported.

The apportioning of blame depends in part on where you begin the story. The regulatory patchwork criticised by the inquiry is a result of the Building Act 1984, which swept away hundreds of pages of statutory regulation and replaced them with short, performance-based requirements (‘the external walls of the building shall adequately resist the spread of fire’). This was a significant change, undermining the statutory building regulations established after the Great Fire of London in 1666, which mandated building in stone and brick, and set minimum street widths intended to prevent the spread of fire. According to Ian Gow, Thatcher’s minister for housing, the regulations brought in by Harold Wilson’s government in 1965 were excessively prescriptive, encumbered an increasingly specialised and diverse construction industry, and could not keep pace with technological change and new materials. Because these regulations were set out in a statutory instrument, the government claimed – not without reason – that they were labyrinthine, hard to understand and difficult to update.

The requirements of the 1984 Act were stipulated in ministerially issued Approved Documents, which were not much less arcane than the regulations they replaced. Much of the inquiry turned on the inadequacy of the fire safety standard (‘Class 0’) that the cladding was supposed to meet and the poor drafting and unclear language of the guidance. The risks posed by deregulation were clear to some at the time, especially the move to part-privatise testing and the certification of materials. Inertia and a broad acceptance of the Thatcherite settlement left future governments reluctant to change it. John Fraser, then Labour MP for Norwood, warned against the ‘economic interdependence’ a private testing regime would create. ‘That would be extremely dangerous,’ he told Parliament in 1983. ‘The building industry’s record in respect of graft, corruption and collusion is not a happy one.’ The Labour MP Gerald Kaufman called it ‘legislative provision for institutionalised negligence’.

Evidence confirming these suspicions began to accumulate. A cladding fire in Huyton, Merseyside in 1991 didn’t result in any changes to the guidance; indeed the inquiry disclosed ‘a request from M. St Press Office’ – the Marsham Street office of the Department for the Environment, which had overseen the refurbishment – ‘to play down the issue of the fire’. Successive governments, including Blair’s, ignored or suppressed warning signs. Cladding-related fires in the 1990s prompted Select Committee hearings and a 1999 report that recommended tougher standards. ‘We do not believe,’ its authors wrote, ‘that it should take a serious fire in which many people are killed before all reasonable steps are taken towards minimising the risks.’ The government declined to act. Brian Martin, the mid-ranking civil servant who had been in charge of fire safety regulations for seventeen years at the time of the fire (he described himself at the inquiry’s hearings as a ‘single point of failure’), suggested a requirement for non-combustible cladding would have been seen as ‘impracticable and unduly onerous’.

The fire at Lakanal House in Camberwell in 2009 is widely seen as the closest precursor to Grenfell. Six people died in the fire, which travelled through the building’s external cladding. Evacuation failures and smoke spread were significant issues. The Grenfell report states that the response of the Department of Communities and Local Government (DCLG) was inadequate and the BRE’s investigation ‘prematurely and unreasonably curtailed’, fitting a ‘longstanding pattern’ of reluctance to deal with the unclear wording of the guidance. The distribution of responsibilities for building safety across different departments is a major preoccupation of the report. Melanie Dawes, the permanent secretary at the DCLG at the time of Grenfell, claimed that she first heard of Lakanal House only after Grenfell. When the coroner investigating the Lakanal fire wrote to the department with safety recommendations, including the installation of sprinkler systems and a systematic review of regulations, Martin told his colleagues: ‘We only have a duty to respond to the coroner, not kiss her backside.’

It is easy to make a villain of Martin, and it is in some ways deserved. He was dismissive and complacent. Reluctant to inconvenience the construction industry, he needlessly curtailed fire investigations, phrased essential guidance on cladding materials ambiguously and assured ministers immediately after Grenfell that the cladding used there was ‘effectively “banned”’, when he knew it was not. But his superiors offered little oversight. The coroner’s letter was addressed to the minister in charge of the department, Eric Pickles, the Cameron-era axeman who once accused those complaining about government cuts of ‘shroud-waving’.

Pickles’s contemptuous evidence to the inquiry was its lowest point. He told the inquiry’s counsel not to waste his time – ‘I do have an extremely busy day meeting people’ – and confused the number of dead with Hillsborough. His irritability was prompted by questioning that focused on the Cameron government’s deregulation drive. Martin told the inquiry that ‘regulation was a dirty word’ in the department. Pickles insisted that safety regulations were exempt from the government’s ‘one in, two out’ deregulatory drive, an assertion the inquiry found was ‘flatly contradicted by [the evidence] of his officials and by the contemporaneous documents’. The report is clear that ‘the pressure within the department to reduce red tape was so strong’ that it prevented a proper response to the Lakanal coroner’s recommendations, which included a revision of the regulations on cladding and the retrofitting of sprinkler systems within blocks such as Lakanal and Grenfell.

Other former ministers bear significant responsibility. Brandon Lewis, fire and policing minister under Cameron, implacably opposed the creation of a fire safety regulator, despite evidence that self-regulation was failing; his successor as housing minister, Gavin Barwell, ignored repeated warnings from MPs on fire safety. The report makes clear that ‘the government’s deregulatory agenda’ was so pervasive that ‘matters affecting the safety of life were ignored, delayed or disregarded.’ Cameron’s promise to ‘kill off the health and safety culture for good’ had far-reaching effects. Grant Shapps’s ‘deletion’ of the Tenant Services Authority – ‘the TSA is toast,’ as he put it – knocked out a crucial way for tenants to challenge their TMO. The inquiry’s finding was significant enough for Cameron to feel the need to respond on X, claiming that the report found that fire safety was ‘explicitly excluded’ from his anti-red tape drives. That is, at best, highly misleading. Pickles and Barwell were elevated to the Lords in 2018 and 2019. Lewis was knighted last year.

The report says that Pickles’s department was ‘poorly run’. According to one of his ministers, he regarded the department’s officials as ‘Guardian-reading pinkos’, but whatever their views were, they acted in line with his antipathy to ‘regulatory madness’. At the inquiry, José Torero, a professor of engineering at UCL and a specialist in fire safety, pointed out that the department had misunderstood statistics about fire deaths and safety policy which it claimed supported its position. Pickles claimed frustration at civil servants’ failure to present policy options to him directly; their reluctance to present ministers with inconvenient facts is a recurrent feature of the Grenfell story. But the culture of a department depends on the ministers at its head. Martin was thoroughly acclimated to his department’s culture: in an email chain about electrical safety, he said that allowing campaigners to advise on fire safety standards would be bad news for ‘UK plc’. Asked by the inquiry what would happen if someone who put an absolute priority on safety were in charge of regulation, he replied that ‘the country would be bankrupt … We’d all starve to death ultimately, I suppose, if you took it to its extreme.’

Church House sits off Broad Sanctuary, a complex of function rooms and offices orbiting a large assembly hall. The view over Dean’s Yard includes Westminster School, the abbey and the Houses of Parliament. Some of the pupils will move from one part of this cluster of buildings to another. The hall is home to the Church of England’s General Synod, but for a week in January this year it hosted days of harrowing testimony from survivors of Grenfell and the victims’ families.

The Grenfell Testimony Week arose from the £150 million civil settlement between the survivors and the corporate and civic parties involved in the fire. The civil claims proceeded in parallel to the inquiry and the testimony week was the result of unhappiness among the survivors that those responsible had not had to listen to accounts of the consequences of their actions. Company executives and government officials were requested to attend, carefully separated from survivors, families and press. In adjoining rooms, work by survivors hung alongside video documentation of Forensic Architecture’s reconstruction of the fire. On successive evenings, the families, the corporate parties and the press were invited to watch the final half-hour documentary, a synthesis of footage and survivor recollections, mapping the spread of the fire through the tower. The evening I saw it, the room remained in silence afterwards.

Most of the 23 defendants to the case sent representatives. Arconic extended the contempt it had shown throughout the inquiry by refusing to send anyone: the company was represented by three empty chairs. Michael Gove, secretary of state for the environment at the time of the fire, attended one session. Press attendance was sporadic, save for Apps. Each day began and ended with a reading of the names of the 72 dead, but each speaker served as a reminder that many more were affected: those bereaved, living with survivors’ guilt or PTSD; those injured and disabled by the smoke; those who died in despair afterwards. The speakers didn’t apportion the blame evenly. Many could not understand or forgive the LFB’s failure to evacuate the building. But harsher criticism was on the whole reserved for the authorities and the manufacturers, who were, in one survivor’s words, ‘party to a national atrocity’. A number of residents spoke of the strength of community spirit. Some hoped that their testimony might stoke guilt – and spur action – among the corporate audience; all agreed that there could be no real justice until those responsible were behind bars.

The effect of testimony is cumulative. Just as Forensic Architecture uses multiple angles and individual memories to collate a mosaic picture of an event, so the scale of grief and injury only becomes clear when we listen to account after account. A single narrative cannot do justice to horror on this scale. Hanan Wahabi and her family lived on the ninth floor of the tower. At the urging of her 16-year-old son, Zak, they ignored the advice to stay put. They got out in time. Her brother, Abdelaziz, who lived on the 21st floor with his wife and three children, did not. Wahabi rejected any attempt to cast the testimony week as ‘some nice healing process’. ‘I will not spare you,’ she said. ‘I hope it remains seared in your soul.’ The fire destroyed her marriage, and eventually claimed the life of her former husband. We heard parts of the hour-long 999 call, reconstructed by actors, during which her brother was told to stay in his flat, told that help would come. ‘It haunts me the way they were spoken to,’ Wahabi said. ‘It haunts me that they were told someone was coming.’ Even in a reconstruction, it is terrible to listen to someone realise they are going to die, as Abdelaziz did. Wahabi addressed the representatives directly: it was ‘your individual and collective actions [that] led to this’, she told them. ‘You covered my home in petrol.’ Her brother’s family were ‘murdered in their own home’: justice ‘must involve prison sentences’.

The most shocking evidence heard by the inquiry concerned the manufacturers and testing bodies. The report’s final judgment is that all the companies involved were guilty of ‘systematic dishonesty’, which eroded the system of standards supposed to protect citizens. The sheer scale of this dishonesty can sometimes be lost in the detail of the way it was accomplished. Not much of Kingspan’s insulation was used at Grenfell, but the company’s manipulation of testing routes ‘knowingly created a false market’ in unsafe insulation. In 2008, when a contractor raised issues about the insulation’s safety, one manager forwarded the email to a friend, joking that the contractor was ‘getting me confused with someone who gives a damn’. Another, texting a colleague about the safety certificate, joked: ‘All we do is lie.’

Most of the insulation on Grenfell was manufactured by Celotex, a subsidiary of the French multinational Saint-Gobain. Its product was formulated to compete with Kingspan’s after its executives realised they could also exploit the lax certification regime. At first it failed to pass the tests conducted by the BRE, so in 2014 Celotex rigged a test by inserting fire-resistant magnesium oxide boards into the insulation. Despite protests to the contrary during cross-examination, recordings of the test in which officials mention boards, and the obvious difference in the thickness of the insulation, evident in photographs of the test rig, make it clear the BRE knew the system was being gamed. Celotex later tried to get the photographs of the boards removed from the file. The magnesium oxide boards were never intended to be used in the finished product. Without these compromised tests, this insulation would not have achieved certification and would not have ended up on Grenfell Tower.

Arconic’s flammable cladding has received the most attention in the press, although the toxic smoke from the insulation behind the cladding panels played a significant role in the deaths at Grenfell. The report makes clear that Arconic also manipulated the testing regime, concealing results that should have seen the cladding taken off the market long before it was put on the tower. In 2004, a French test carried out on the cladding in the form it was attached to Grenfell – a flat sheet with a polyethylene core bent at the edges to form a ‘cassette’ which hangs from a skeleton frame – revealed it burned ten times faster, and released three times as much smoke, as in the other form (a riveted version) in which it was manufactured. The cassette version of Reynobond PE was so dangerous that the test was aborted: it didn’t even receive the lowest possible grade. Claude Wehrle, Arconic’s technical sales manager, dismissed this as a ‘rogue result’ and suppressed it. Unless the company chooses to disclose them, a laboratory can’t share ‘commercial confidential’ test results, even with the standards boards of foreign governments. The cladding was allowed to be sold in Britain because the test results conducted on the ‘cassette’ panels were omitted. In late 2013, the riveted panels were downgraded to Euroclass E – but continued to be marketed as Euroclass B (equivalent to UK Class 0, the minimum required on a British building taller than 18 metres). When the British Board of Agrément reviewed the certificate of the Reynobond PE panels in 2015, it wasn’t told about this downgrade: Arconic simply ignored its emails. The BBA renewed its certificate.

Wehrle’s internal messages are damning. They reveal that managers at Arconic knew about the dangers of polyethylene-core cladding years before Grenfell was refurbished. In response to a safety query from a Spanish manufacturer, Wehrle said that the fact they had not managed to have the cassette panels certified to Spain’s minimum standard, Euroclass B, should be kept ‘VERY CONFIDENTIAL!!!!’; a few months later he told the same employee, in response to a query from a Portuguese company, that ‘we’re not “clean”.’ Regulations in most of Europe meant that cladding used on high-rise buildings had to meet stringent fire-retardant standards. But Wehrle wrote in a report in 2011 that ‘we can still work with national regulations who are not as restrictive.’ This included the UK.

Arconic is a US-owned multinational, but operates in Europe through a French subsidiary. Several of its executives, Wehrle included, hid behind an arcane French law to avoid attending the inquiry. This statute was intended to protect French citizens (and companies) from the aggressive disclosure practices of American antitrust law. It prohibits individuals from sharing evidence ‘of an economic, commercial, industrial, financial or technical nature, with a view to establishing evidence in foreign judicial or administrative proceedings’. Despite a note verbale from the French government stating that it didn’t consider the inquiry’s proceedings to fall under this provision, Wehrle and two other Arconic witnesses continued to refuse to attend. The evidence on which they would have been questioned was presented without them. Claude Schmidt, the company’s president, who did attend, accepted that Arconic had obtained its certification in the UK through ‘misleading half-truth’. Had the fire not happened, he admitted, the lethal test results ‘would have remained secret’. The inquiry found a pattern of ‘deliberately concealed’ test results.

Inquiries into political scandals often run up against the careful use of private channels and a reluctance to record damaging information in emails. What is startling about much of the evidence in the Grenfell inquiry is that executives, salespeople and officials openly acknowledged their wrongdoing. A culture of deceit and irresponsibility was deeply embedded in the building industry and there is little reason to think anything has changed. It has long been indulged by state bureaucracies: Michael Gove recently claimed that his efforts to sanction the manufacturers after the fire were impeded, and eventually obstructed, by the Treasury. Under cross-examination, witnesses spoke of becoming ‘embroiled in the culture of a business’ which dismissed safety concerns and incentivised evasion. One Celotex employee, reflecting on his failure to note concerns with the rigged test, went further: it was ‘a failure of courage, and a failure of character, and a failure of moral fibre on my part not to do so’.

The behaviour of the cladding and insulation companies was so flagrant that it attracted much public criticism during the inquiry. Less attention was paid to the actions of the testing and certification bodies, although their ‘standards’ had become, as one of the lawyers for the families put it, a ‘route to market rather than a route to safety’. Both the BRE and the British Board of Agrément are criticised for incompetence, carelessness and complicity with the industry. Both are private bodies (the BRE was a government laboratory until 1997) and, as such, have to seek testing contracts from industry, though the BRE also retains government investigative contracts. As early as 1999, BRE officials made clear to MPs that ‘commercial pressures’ guided their work. But a reluctance to inconvenience the industry, and inadequate work on fire investigations, pre-date privatisation: the removal of the ‘public interest’ element simply served as an accelerant. The tendency for people to move between industry and regulation accounts for some of this, but it also suggests that stronger and more effective regulation can’t be achieved at a stroke. In 2012, the government varied the conditions of its fire investigation contract with the BRE, stipulating that its reports should ‘not contain any policy recommendations’ or ‘any proposed text’ for revised regulation. If the regulatory structure was a ‘house of cards’, as one of the lawyers put it, an ‘ideal prop to facilitate industry capture’, it was made that way by government.

In exposing building manufacturers as deceitful, regulators as complicit and officials as compliant, the Grenfell inquiry has led to much wider questions. How many products slipped through the certification net? How many remain on buildings now? How deep is the rot? The casualness with which officials, executives and marketing staff flouted regulations, the ease with which they practised ‘systematic dishonesty’, is bound to have reached further than the products used on Grenfell. After all, this kind of deception is good business sense. And regulatory evasion is so entrenched in the operations of many companies – and not just in the building industry – that any regulator needs to be adroit, independent and properly funded: it’s implausible to expect any regulator to remain sufficiently rigorous if it is forced to rely on commercial contracts. As one BRE email put it, anything that promises to be a ‘huge source of income’ is also a ‘huge liability’.

Sheila didn’t use her surname. After the end of a difficult marriage, she began again. At 84, she was the oldest resident to die in the fire; in the words of her family, speaking publicly for the first time at the testimony week, she was ‘84 going on 44’. One granddaughter described her as ‘proud, eccentric and loving’: a devotee of the Maharishi and meditation, alternative therapy and swimming. She had lived at Grenfell for 34 years. The inquiry reported that she died in her bed from asphyxiation, probably still asleep.

Her son described the neglect she had long suffered at the hands of the TMO. Failure upon failure by an ‘unsympathetic and unprincipled municipal landlord’ left an 84-year-old woman without gas or water in her flat for a period during the refurbishment. Her daughter-in-law rounded on the corporate representatives, speaking especially to the council and the contractors: ‘Things are not different. They haven’t changed.’ The TMO treated tenants as ‘second-class citizens’: ‘watching you,’ she said, ‘I don’t see any remorse.’

Unlike most such organisations, which handle a single building or an estate, the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation ran all of the borough’s housing stock – nearly ten thousand units. Explanations for this arrangement differ: those sympathetic to the council argue that it helped defend the social housing stock from sell-offs, others see a council that has always been conflicted about its social estate shrugging off its responsibilities. After its creation in 1995, the TMO rapidly became a high-handed bureaucratic oligarchy, which concealed its failings – including deficiency notices issued by the LFB – from those tasked with scrutiny. Its attitudes to tenants frequently degenerated into outright hostility. Across the estate, the TMO had built up a backlog of 5400 repairs by 2017; any repairs that were carried out were often substandard.

None of this is unusual in Britain. Many landlords behave like the Kensington and Chelsea TMO: unresponsive, hostile, capricious and desperate for cash. Yet some aspects of its conduct exceeded even the grubby profiteering typical of landlordism. By 2009, its relationship with tenants had deteriorated to such an extent that an independent review commissioned by the council quoted tenants describing it as ‘malevolent’. ‘This is an unhappy culture and it needs to change,’ the report said. The deterioration of the estates and the backlog of repairs were the causes of the breakdown; KCTMO’s imperious attitude compounded it. The appointment of a new chief executive, Robert Black, was supposed to rebuild trust. But early improvements proved ephemeral. The organisation tried to avoid fitting or repairing self-closers to flat doors across the estate (these help prevent fire and smoke from spreading) and to defer the ‘additional expense’ of establishing an inspection programme recommended by the LFB (Grenfell’s malfunctioning self-closers were an important vector for the spread of toxic smoke). The TMO’s sole fire-risk assessor, Carl Stokes, was ‘allowed to drift into’ the job on the basis of a CV that included a number of exaggerated qualifications. A former firefighter, Stokes represented a less ‘rule-bound’ approach, as an email from the TMO to the council put it, than the organisation’s previous assessment firm. In April 2017, responding to an email about cladding safety after a fire in Shepherd’s Bush, Stokes claimed that questions had been asked about fire safety and assurance received from Rydon, the main contractor on the refurbishment. They had not.

The TMO’s failings and its dysfunctional internal culture are important because it commissioned and managed the Grenfell refurbishment. Its executives were directly responsible for the choices that were made. Yet it behaved like a fiefdom. The inquiry found Black had engaged in a deliberate ‘pattern of concealment’ over the disclosure of fire safety issues, while the TMO had acted, again according to the residents, like ‘an uncaring and bullying overlord, which belittled and marginalised’ Grenfell residents. Tenants who made a fuss were branded malcontents and agitators.

Ed Daffarn, co-founder of the Grenfell Action Group, which campaigns against ‘social cleansing’ in Kensington and Chelsea, warned in a 2016 blog post that only a ‘catastrophic event’ resulting in ‘serious loss of life’ would make people pay attention to the TMO’s ‘malign governance’ and ‘ineptitude and incompetence’ on fire safety. Daffarn’s vocal opposition made him a hate figure in the TMO; Black even asked housing officers to ‘do a bit of checking’ on his tenancy. Others used his campaigning as a pretext for withdrawing from public consultations with Grenfell residents over the refurbishment.

Daffarn could lay it on thick, but that’s the point: an activist needs to be relentlessly annoying, to the point of myopia, to demand attention for an issue otherwise easily dismissed. And he was very often right. In 2012 he asked whether Studio E, the architect appointed for the refurbishment, had any experience with high-rise buildings – and if not, why it had been given the job. It had no such experience, but Daffarn never received a direct answer. The TMO’s withdrawal from public consultation over the refurbishment meant that Grenfell residents weren’t informed of the decision to use ACM cladding rather than the zinc panels initially planned. If he’d known to look, a campaigner as diligent as Daffarn would almost certainly have found out about the two ACM cladding fires in the UAE not long before.

There is no doubt that the TMO and its executives bear significant responsibility for the fire. But it has also proved a convenient scapegoat for other implicated parties, especially since it no longer manages the borough’s housing stock and continues to exist as a legal entity only to deal with the aftermath of the disaster. The inquiry is circumspect in its criticism of the council and stronger in its criticism of housing officers than councillors. It says that Kensington and Chelsea’s building control department, the ‘last line of defence’ on fire safety, ‘wholly failed’ in its statutory duty to protect the public. The ‘considerable responsibility’ for the fire that the inquiry apportions to the department extends far beyond inspectors such as John Hoban, who wept while giving his evidence. It was ultimately his responsibility to determine whether the refurbishment and its materials met safety standards. Hoban described a department that had cut nine experienced inspectors and replaced them with one recent graduate; he was overloaded, often working all weekend. During the Grenfell refurbishment he had an additional 55 projects added to his workload. At the start of the inquiry, the council apologised for failings in its building control department, but during Hoban’s testimony it felt as though those failings were a convenient focus, distracting attention from wider issues.

Kensington and Chelsea’s Tory councillors barely appear in the report. The council’s ideological motivations were outside the inquiry’s terms, but in the immediate wake of the fire they were the focus of popular outrage. Its aristocratic deputy leader, Rock Feilding-Mellen, who also held the council’s housing portfolio, seemed a perfect villain. He was a property developer himself, and journalists tracked his dinners with major developers and jaunts to MIPIM, ‘the world’s leading property event’ in Cannes. Campaigners accused him of having referred to North Kensington as a ‘dung heap’ in council meetings; in a local freesheet he stated his desire to ‘wean people off the expectation of being put up in prime central London locations’. An opposing argument eventually emerged in the press, insisting that the council had been maligned: beneficent and detached patricians, lumbered with an ungrateful tenantry and incompetent TMO, their sins were, in the scale of things, minor.

The evidence presented at the inquiry certainly demonstrated Feilding-Mellen’s detachment from the project. His most significant recorded interventions were over the colour of the cladding. He seems to have given no direct thought to fire safety, suggesting in his evidence that he simply assumed it was being taken care of somewhere down the chain (the LFB’s guidance, sent to councillors in 2014, warns them ‘not to make assumptions’). One of Feilding-Mellen’s more pressing concerns was that refurbishment would not obstruct later ‘regeneration’ – the potential demolition of the tower and its replacement with mixed-tenure housing. He raised the issue when first hearing of the plans in 2012; it was still on his mind a year later in an exchange with Nick Paget-Brown, the council leader, who suggested the refurbishment was a good ‘dry run’ ahead of ‘actual estate renewal’. As for the general effect of the council’s cost-cutting disposition, during cladding negotiations between the TMO and its main contractor, an ‘urgent nudge’ email to the contractor notes ‘we need good costs for Cllr. Feilding-Mellen and the planner tomorrow.’

While it omits broader questions of political responsibility, the report describes a succession of failures by Rydon – the refurbishment’s main contractor – and the subcontractor responsible for the cladding, Harley Facades; the project’s architects, Studio E; and their fire consultants, Exova. The report characterises these as acts of negligence, omission and carelessness towards contractual responsibilities, attributing to them ‘considerable’ or ‘very significant’ responsibility for the fire. There are details that seem to defy belief: Exova’s failure to visit the site after the preliminary stage; Harley’s appointment of the owner’s 24-year-old son as project manager; a late email from a TMO official to Rydon asking for details on fire safety that was never followed up. It’s obvious from the report’s recommendations that such irresponsibility is thought to be endemic in the industry.

Rydon’s appointment as main contractor for the project was irregular, even improper. Although Rydon had put in the lowest bid for the project, the TMO wanted to save another £800,000. Before appointing Rydon, it conducted clandestine meetings to guarantee this reduction. Part of the saving came from downgrading the cladding, and Rydon planned to understate the saving and pocket the difference (an internal email gloats that ‘we will be quids in!’). It might seem obvious that a ‘value for money’ exercise that turned a building into a deathtrap showed an excessive focus on cost, but not everybody sees it that way. Examining Peter Maddison, the TMO’s director of regeneration, Millett asked whether there had been serious discussion over whether Rydon’s bid was ‘abnormally low’:

Maddison: I think there was consideration given to this, and in reality the project was delivered on budget, so that’s the best sign as to whether or not the price was the correct price.

Millett: Well, Mr Maddison, if I may say so, the fact that the project was delivered on budget is not of great assistance to us, given that we know what happened to the building.

Feilding-Mellen left Kensington and Chelsea Council after the fire, retreating to his family’s Tudor estate. In an article for Newsweek published last year, he complains of having been a ‘lightning rod’ for discontent. He describes a fall into nihilism and despair, eventually redeemed through taking a role in the family business. He rediscovered ‘optimism and a sense of possibility’ through ‘psychedelic therapy’ in Jamaica. Feilding-Mellen is by no means the guiltiest of the guilty men of Grenfell, but he was responsible for the council’s housing portfolio and no trace of that responsibility, no grappling with its consequences, mars his ‘personal journey’ to a ‘new beginning’ (the family business provides retreats ‘to those looking to grow and improve their wellbeing through the legal use of psilocybin’).

Few of those who lost their homes and neighbours on the night of the fire have had his opportunities for healing. Paul Menacer couldn’t stop his leg from jumping while he gave testimony. He had moved into Grenfell permanently in 2016 as a carer for his uncle, and escaped his flat on the sixth floor. (His uncle was in Algeria on the night of the fire.) He had lost both his parents when he was fourteen, ‘but Grenfell hit me harder.’ ‘I’m not even 1 per cent of the guy I was,’ he told the inquiry. His experience of neglect in the aftermath of the fire is echoed by other survivors: he spent six months waiting for NHS mental health treatment before the case was closed against his will. During the Covid lockdown, he began to hear voices; he only realised what was happening to him after police intervention. His medication makes him feel like a ‘zombie’ or a ‘scarecrow’. There have been at least three suicides and twenty attempted suicides since the fire, including among emergency service workers.

Moore-Bick’s report makes 58 recommendations to the government. Some would be transformative, such as sweeping away the fragmented and dysfunctional regulatory landscape and replacing it with a single construction regulator, reporting to a single secretary of state. Others fix obvious defects in professional registrations and licences (currently anybody can declare themselves to be a ‘fire engineer’) or recommend thorough reviews of guidance. Some are oblique proposals to remedy the effects of austerity on the Fire Brigade. In other areas the report is restrained: it proposes nothing on tenant representation, deferring to the Social Housing (Regulation) Act 2023, which strengthens the regulator’s investigatory power, permitting it – in principle – to inspect much more proactively and to issue unlimited fines. The absence of real means of accountability and representation was key to the disaster, and it isn’t clear that the new Act will do much to remedy this. Similarly, the inquiry’s recommendations are couched firmly within the post-1984 paradigm: even where it finds current guidance lacking, it doesn’t suggest a return to statutory, prescriptive standards – a possibility raised by some of the most credible expert witnesses, including the fire safety expert Barbara Lane, who called Kingspan’s insulation an ‘accident waiting to happen’ and refused to sign off on it. Such a shift would amount to a wholesale change in the way construction is carried out in Britain. Its advocates claim that it would have prevented the ambiguous wording and irregular test environment that led to Grenfell being clad in combustible materials. Substandard fire doors, broken self-closers and inadequate smoke ventilation all contributed to the deaths in the tower and all of them remain issues across Britain’s ageing social housing stock. By refusing to specify minimum standards, the current regulation leaves it up to the industry to determine how best to avoid fires. Advocates of a return to prescriptive standards are right that the construction industry does not deserve the trust inherent in such light regulation.

Welcoming the report in Parliament, Keir Starmer promised to study the recommendations and respond in full within six months. Some are sufficiently complex to merit study, but Labour’s determination to avoid spending also lies behind the delay. The report’s regulatory measures will cost money if they are to be effective: no regulator can constrain private rapacity without meaningful enforcement powers. One recommendation is for a government-level record of its responses to recommendations from coroners, select committees and public inquiries, with parliamentary oversight and scrutiny. This emerges from successive failures to learn or act from inquiries into fires, especially Lakanal House. After public inquiries have reported, they cease to exist: nobody monitors or enforces their recommendations, which are often politically awkward or expensive. But it wouldn’t be difficult to create a unit in the Cabinet Office responsible for this, and to improve the current absurd situation, in which public inquiries are lavishly funded at great length to discover uncomfortable truths that everyone proceeds to ignore.

For the survivors, nothing short of criminal charges and prison sentences for those responsible will be seen as justice. Potential charges mooted by the police range from fraud and misconduct in public office to manslaughter. Making criminal inferences from the inquiry’s report, even where it assigns responsibility, is difficult given the differing burdens of proof. The attorney general gave an undertaking in 2020 that no individual giving oral evidence to the inquiry would have that evidence used against them. Many fear that this will hamper prosecutions, but the assurance is narrowly drawn: it does not prevent cross-use against other individuals, nor does it apply to documentary evidence, nor to the corporations as such. The inquiry’s meticulous narrative, including the short inquests for each victim, will surely form the spine of prosecutions. But the precedents make unwelcome reading: the collapse of the manslaughter trial after the Herald of Free Enterprise disaster, or the absence of charges following the Piper Alpha explosion. The Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act 2007 has mostly resulted in the prosecution of small firms, whose culpability is easier to prove. Yet the inquiry has uncovered a considerable number of acts of willed deception, systematic fraud and deliberate evasion of safety standards. If ever a case should serve as a reminder that no company, however ramified its structure or large its reserves, can evade accountability for deaths, it is this one.

Gillian Kernick, a former Grenfell resident, wrote in her book Catastrophe and Systemic Change (2021) that one of the reasons the state fails to learn the lessons of disaster is the difficulty in ‘making the water visible’. The phrase comes from the old story of one fish asking another ‘What’s water?’, a way of talking about conditions so pervasive they can no longer be perceived. The inquiry can be read in a minimalist way: reading the recommendations in isolation, Grenfell can be seen as an instance of severe regulatory failure, exacerbated by incompetence and corporate malice, one that is best addressed by specific but limited reform to construction and government guidance. The maximalist reading, which emerges from the full report and its evidence, suggests the problem is much more extensive. It is an indictment of an entire philosophy of governance, one that favoured the deliberate withdrawal of state authority and enforcement from areas of life where citizens rely on regulation – by a party not beholden to commercial interests – for their safety and security.

Whatever freedoms it affords, the costs of deregulation are too obvious to ignore. It is irrational and irresponsible to leave safety, and the certification systems that underpin social trust, to companies incentivised to undermine it. Austerity, and its political acolytes both local and national, got rid of many of the remaining safeguards against disaster. Grenfell should have been a moment of change in the way we think about housing, yet Grenfell-style cladding remains unremedied in blocks across the country, despite government schemes to fund its removal.* Most high-rise buildings (more than 18 metres high) have been remedied, but even identifying all of the medium-rise buildings (those more than 11 metres high) clad in ACM panelling has been difficult: construction experts suggest that there may be thousands. London councils warn of a need to make £170 million in cuts to balance their Housing Revenue Accounts over the next four years. Yet housing stock built a generation or two generations ago now needs significant attention. Starmer apologised ‘on behalf of the British state’ for its failure to fulfil its fundamental duty, but the conditions which caused the fire remain. ‘It’ll happen again,’ Willie Thompson, a survivor of the fire, said in 2019. ‘Another Grenfell’s in the post.’

During the course of the inquiry, I sometimes asked officials and politicians to reflect on the fire. Most inclined to minimalism: it was a serious catastrophe, a tragedy, but of a kind that is rare in Britain. It is never explicitly stated, but occasionally implied, that the people who suffer in this kind of disaster are just unlucky. Grenfell, however, is only the most prominent of these catastrophes. Taken with the other inquiries that ran alongside it – on infected blood, child sexual abuse, mental health deaths, undercover policing – a picture emerges of a country that is consistently failing its vulnerable or dependent citizens, who have no way to voice their complaints and no one to champion their cause, and that is all too unwilling to confront or constrain the powerful.

In his closing remarks to the part of the inquiry that heard accounts of each death in detail, Millett remarked that the panel might be ‘struck by the vast distances between the final terrible experiences of those who died’ and the technical decisions made by testing houses and manufacturers and local authorities. Yet ‘every decision, every act, omission, interpretation, understanding, practice, policy, protocol, affects someone somewhere, someone who is unknown and unseen, but who is an adored child, a beloved sister, a respected uncle, a needed mother.’ Distance has characterised the Grenfell story from the start: distance from power, consideration and redress. Yet the most terrible and unjust distance now seems to be time. On the anniversary of the fire this year, survivors carried placards that read: ‘This much evidence, still no charges.’ Every death at Grenfell was foreseeable. Every death was avoidable. For every death, therefore, someone is responsible. ‘It’s always the same thing everywhere – we suffer and they prosper,’ Karim Mussilhy, whose uncle died in the fire, told the inquiry. ‘The system isn’t broken, it was built this way.’ Only prosecutions will prove him wrong.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.