Sometimes I’ve thought the whole idea of pleasure in Western art has been mortgaged by the French. Or maybe the Franco-Hispanic-Italo-Anglo-Dutch. It’s their artists, their subjects, their landscapes, their models, their faces. Their trees and their hills. Their beauty and beauties, their colour and light. In the current scene a few of the bad boys – long since turned grand old men – may be Germans (Kiefer, Richter, Baselitz), but, further back, isn’t there something displeasing about older German samplings? Something freakish, astringent, minoritarian, inturned? Say, Dürer, Dix, Liebermann and Nolde. Their canvases have a way of appearing muddy, frizzy, dowdy, scratchy, sometimes all at once. Perhaps it’s just the best we can do. Perhaps we should have stuck to philosophy.

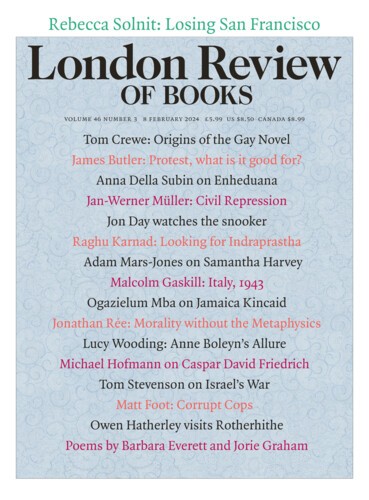

Caspar David Friedrich is a possible exception. Born in 1774 in Greifswald on the Baltic coast, he studied painting in Copenhagen and in 1798 moved to Dresden, the so-called or self-styled ‘Florence on the Elbe’, where he died in 1840. A major retrospective of his work is currently on show at the Kunsthalle in Hamburg (until 1 April). It commemorates the 250th anniversary of his birth and will travel across the Atlantic next year to give Friedrich his first US solo show, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

There was a rumour that Friedrich was of aristocratic descent, but it’s never been proved and I take it to be a bit of sentimental mythmaking. (Isn’t it hard enough being a German artist without being a commoner?) He was from a large, devoutly Protestant family; his father was a soap boiler and candlemaker; his brothers were artisans or tradesmen. Friedrich had money worries for most of his life. Whether from preference or modesty or lack of means, he began as a draughtsman and didn’t try his hand as a painter until the turn of the century. His two gifts – one the management of line, the other the control of perfect, unmarked gradations of colour (look, no lines!) – remained discrete in him and, on occasion, seem at odds with one another, so that the eye clings fast to the horizon or wobbles about the sky. The human figures (tiny when present) can seem a little cartoonish in his dismal or majestic settings. His pencil and ink drawings – a hundred of them are on show at the Kunsthalle – are sensitive, skilful and laboured over, faint, delicate sketches of trees, rocks, clouds, the occasional crumbling thatched cottage or decayed graveyard. They look like accidental daguerreotypes, a boulder, a bush, a long shot of an inconsequential landscape. You can hear and smell some of his trees. The execution or performance of so much detail in such a small space makes them seem almost private. It is typical of Friedrich that his subjects confer little obvious value. His landscapes are not working landscapes; they have slipped the bonds of ownership; they offer no return. It is the rustic poverty of Dutch painting without the cheerfulness and pride of the Dutch, the lino-and-lobsters of their smakelijk interiors. The Germans have a word for ‘cosy’ (gemütlich) so notorious it has practically entered English, but you won’t find any of that quality in Friedrich, where the buildings are all dilapidated, the trees crucified; the churches are ruins, the humans totems or tokens. It feels like the very essence of North, with a little admixture of East, to rub it in. I can think of no other artist, except Turner, so fascinated by the marginal contrasts and collisions between fog and cloud and mist, and so brilliantly equipped to capture them.

Friedrich’s works are modestly sized. Even the famous ones (The Monk by the Sea, The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, The Sea of Ice, Moonrise over the Sea) are not large – surprisingly small, even – so that they don’t get single billing in the reasonably proportioned rooms of the Kunsthalle. They took him a long time to complete, and his prices (based on size) weren’t high. One might have supposed he could sell to a rising bourgeoisie, but either such a thing didn’t yet exist in early 1800s Saxony, or the pictures didn’t appeal to it: unpeopled craggy landscapes or beauty spots partly occluded by the backs of others, early instances of Germans who laid out their towels first. Gothic wreckage. Tombstones. Fallen arches. Perhaps not what you want in your parlour. Not ‘conversation pieces’ depicting lively social interactions; Friedrich’s humans are in anti-social interaction. They are enacting awe, perhaps inadequacy. Words fail them, whether they are alone or with others.

The wanderer is Friedrich’s typical protagonist. He is lost rather than found in the pictures, hidden rather than lost. Where there is a plurality of humans, there is apt to be something a little absurd about them. Even the titles don’t like to refer to them. In Chalk Cliffs on Rügen, there’s a woman pointing, one man down on all fours, another propped against a tree. Nothing convivial there. No dramolet, no anecdote. Friedrich was lucky enough, via intermediaries, to sell on occasion to royal houses – the king of Prussia, the tsar – but never reliably enough to establish a taste for his work. When there was a sinecure in Dresden going (a professorship in landscape painting), Friedrich was found a smaller one. Many of his encounters with the public or with patrons were humiliating. He endured lectures regarding his colours and his subjects. Following his death, his work fell into decades of obscurity; his son carried on the family tradition, painting animals. Friedrich was rediscovered in the early 20th century, the great age of rediscovery (Hölderlin, Dostoevsky, Büchner, Shelley, Bach). The Nazis predictably cottoned on to him as promising Blut und Boden, but there is no fealty in Friedrich, nothing socially or politically heroic, and the episode merely ended up damaging his reputation again. Even now, he is ‘big in Germany’ (and by implication, nowhere else). The Monk by the Sea is on the cover of the old Leonard Forster Penguin Book of German Verse; I grew up with Friedrich calendars. Almost all the works on show in Hamburg are from collections in Germany, with the rest drawn from here and there in Northern Europe – Norway, Switzerland, Denmark, Finland. Alexander II’s collection, now at the Hermitage, including half a dozen pieces as good as Friedrich’s best, couldn’t be included, any more than sundry works lost to wars or fires or accidents, or which have simply gone missing.

There is something utterly, irredeemably, terminally German about Friedrich. He is bound by the sea and mountains (which became his two great subjects). He never strayed beyond Denmark to the north (where he studied), Poland to the east (where he had an aristocratic pupil) and Bohemia to the south (where he walked and sketched in the Krkonoše mountains, and later convalesced in Teplice). At a time when travellers on the Grand Tour still drew the curtains of their stagecoaches against the horrid Alps (and Shelley wrote ‘Mont Blanc’), he seems to have made it his business to walk and sketch in rough and underpopulated landscapes, small-scale bits of German wilderness, the Harz, the Riesengebirge, the so-called ‘sächsische Schweiz’. Born on the coastal plain, he was drawn to mountains. Late in life, the sea took him back – sailing boats, the Horatian metaphor for individual destiny. He never went very far west, where life softened into agreeableness. When one of his brothers was in France, he wrote him an angry, disapproving letter (Friedrich was against the conquering Napoleon, and yet longed for change in Germany-of-the-little-warring-fiefdoms). He hoped once to visit Switzerland but couldn’t afford to go. Italy he straightforwardly disdained. What Friedrich saw was, give or take, German. Sometimes it shows, often it doesn’t. At sea level, at altitude, what you behold belongs to everyone. You can’t own what he shows. Clouds are common property. Phenomena such as sunsets and moonrises suspend distinctions anyway. So much in him is planetary as much as local. There are no frontiers, no inspectors, no languages. You couldn’t talk to him on days he was painting clouds, his wife said.

What is German is what is unresolved or uncertain. Are the paintings centripetal or centrifugal? Warm or cold? Cold or glacial? Are they momentary – Polaroids – or statements, like a profession of faith, telling us life is this judderingly bleak? Is their point darkness or light? Are they morbid or healthy, or some strange combination of the two? Is the mastery of detail an asset in a painter who, infrared analysis has revealed, often took objects out of pictures – a soft tree downstage in a landscape, a pair of sailing boats in The Monk by the Sea – making them plainer and emptier than ever? Are the paintings humanistic, or does their wilderness appeal to the glimmering of the post-human conscious in us now? Or envy, even? Is there humour in Friedrich’s paintings? (He was capable of it in letters.) The back views of spivvy bourgeois trippers, the confrontation of the ineffable with the inadequate? How much is encoded, in the way that the chasseur is vis-à-vis the German forest? A little lick of helmet-gleam, the deep dark Frostian death-woods. A memory of the retreat from Moscow, or some fresh threat or promise? Some German Birnam Wood? The barrettes (think Wagner) and velvety tunics of some of his humans – you would have to call them deuteragonists – were actually elements of a (forbidden) neo-medieval uniform indicating liberal political opposition, the one that lost to Napoleon, lost at the Settlement of Vienna, and lost again in 1830. Are the religious accents or references in some of the paintings living or grieving? One thinks again and again of the limits of Friedrich: the limits of subject and palette, the proximity to self-parody (which has led to his ‘influence’ now being mostly rather painful vulgarisation). Friedrich was conscious of his limitations, but helpless against them. Even when reduced to the size of a postage stamp, or to black and white, there is no mistaking the pull and the skill and the force of his images.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.