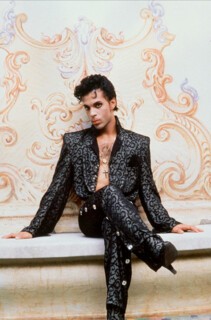

Iwas asked the other day to name my dream man and dream woman, and answered with Charles II and Mrs Oliphant – Charles II being the hottest of British monarchs (admittedly not a strong field) and Mrs Oliphant the most criminally underrated of 19th-century novelists (see The Ladies Lindores). These are two of ‘my people’, in the sense that Nick Hornby uses the phrase, meaning those figures ‘I have thought about a lot, over the years … who have shaped me, inspired me, made me think about my own work’. Hornby’s list is erratic, as anyone’s would be, running from Larry McMurtry through to Barbra Streisand and Arsène Wenger. But two figures stand out, and, he thinks, justify direct comparison. Dickens and Prince: A Particular Kind of Genius (Viking, £9.99) is a book that, far from crying out to be written, was resting very still and mute in a lead-lined coffin at the bottom of the ocean. It has never occurred to me to write a book about Charles II and Mrs Oliphant, but I reckon I could make a fist of it: both were of Scottish extraction, though lived mostly in England; both were natural storytellers (Charles loved to buttonhole people about the time he hid in an oak tree); both were parents of sons (Charles had eight; Mrs Oliphant had two, plus a nephew); both had trouble with those sons (they were expensive, and did too much drinking and lazing about); Charles had three kingdoms to manage and Mrs Oliphant usually wrote three novels a year; both were alive and have subsequently been dead for a long period etc. Resemblances jump out at us all the time, like the cloud in the shape of the queen, spotted over Telford on the day she departed this world. They are usually arbitrary and tell us more about the seer than the seen. They do not usually get packaged up for near simultaneous release on both sides of the Atlantic (the American edition of Dickens and Prince is almost twice as long, the type being much larger).

Hornby knows deep down that it’s silly, and his prose is pleasant enough in a Dad-ish way, but whenever I felt inclined to forgive him, my eye fell on those two editions, and I thought of what it takes to carry an idea through to print, and fortified myself against kindly impulses. ‘Men of genius,’ Benjamin Jowett said in his sermon at Dickens’s funeral in 1870, ‘have greater pleasures and greater pains, and greater temptations than the generality of mankind, and they can never be altogether understood by their fellow men.’ Hornby would agree with this, though not with Jowett’s next bit: ‘We do not wish to intrude on them, or analyse their lives and characters.’ He is in awe of Dickens’s and Prince’s genius and thinks it inexplicable, but tries to explain it all the same, or tries for a few pages by way of admitting failure. Was it something to do with their rickety childhoods (Dickens in the blacking factory; Prince living in his friend’s basement)? Hornby concludes that ‘every tiny step of their lives, every single parental decision, school lesson, friend, uncle, magazine, day out, crush, conversation, shopkeeper, made them that way.’ Ah yes, I nodded: that is so very often the case. Next chapter please, Mr Hornby.

It is nice to be reminded of the scale of both men’s youthful achievement: by thirty, Dickens had produced Sketches by Boz, The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge; Prince had danced his high heels from For You to Lovesexy via Dirty Mind, 1999, Purple Rain and Sign o’ the Times. But there is Wikipedia for this sort of thing, as there is for so much of what follows: Dickens and Prince in the movies, Dickens and Prince as businessmen, Dickens and Prince in their relationships with women, Dickens and Prince as men who died in their fifties.

Even as I resented being dragged into such bonkers territory, I found myself registering omissions. Nothing on the fact that both Dickens and Prince had outsized fashion sense. Nothing, really, on Dickens and Prince as public performers, addicted to audiences. Nothing on Christianity – Prince spent his career in dialogue with its symbols and became a Jehovah’s Witness; for Dickens, Ruskin tutted, ‘Christmas meant mistletoe and pudding – neither resurrection from the dead, nor rising of new stars, nor teaching of wise men, nor shepherds.’ Prince’s ‘Another Lonely Christmas’ (‘’Cause baby, you promised me/Baby you promised me you’d never leave/Then you died on the 25th day of December’) could be about Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim, if Scrooge had never had the benefit of those ghosts. And how strange that Hornby has nothing to say about Prince as a lyricist, as the man who thought of partying ‘like it’s 1999’, of a girl wearing a raspberry beret ‘walking in through the out-door’ and another, called Nikki, ‘in a hotel lobby masturbating/with a magazine’, and who pulled off the thrillingly weird conceit of ‘If I Was Your Girlfriend’ (‘If I was your one and only friend/Would you run to me if somebody hurt you, even if that somebody was me?’). Nor is there any consideration of the musicality of Dickens’s prose, its surprising, jerky rhythms, high-pitched crescendos, sharp stops and fade-outs, the moments when he does the verbal equivalent of Prince doing the splits. Dickens cared for the sound of his writing – he told G.H. Lewes that ‘every word said by his characters was distinctly heard by him.’ His famous public readings weren’t of passages from his books, but of scenes he had rewritten for performance, cutting, condensing and sharpening to maximise the drama or, more often, the comedy. Prince was funny, too, come to think of it.

Like I said – you resent it. Hornby is too invested in his model of individual genius to make good on his occasional claims to be drawing general conclusions (‘What can we learn from looking at two artists, both sui generis … who literally had more than their fair share of talent?’). He is at his most suggestive when he says that this is a book ‘about work, and nobody ever worked harder than these two’. Leaving aside that last invitation for invidious comparison, it is worth thinking about excess in art, about being and producing ‘too much’. The most common complaint about Dickens in his lifetime was that he exaggerated, that his characters were implausible specimens of humanity. Prince, too, was seen as going far beyond the norm, especially in his sexuality (he developed a guitar that could be wanked off over a crowd, spattering them with water; he wore backless trousers at the VMAs). Do we respond more immediately, in every sense, to brilliance that is highly coloured, and do we tire of it sooner, once we are accustomed to it and it begins relentlessly to accumulate?

John Updike wrote of Joyce Carol Oates that ‘after the first wave of stories and novels … crashed in and swept away a debris of praise and prizes, protective seawalls were built, and a sullen tide set in.’ New standards are applied. Resistance builds up. Dickens’s late novels were received unfavourably by many critics; Henry James’s verdict on Our Mutual Friend, that it was ‘poor with the poverty not of momentary embarrassment, but of permanent exhaustion’, is only the most notorious. ‘Exhaustion’ was a favourite accusation made against Mrs Oliphant, though, as her indefatigable bibliographer points out, it usually accompanied an inability to read her novels with ‘understanding or an approach uninfluenced by preconceived ideas’. As he went on turning out album after album (there were 42 in his lifetime, and thousands of unreleased songs), Prince received less and less serious attention. How to account for an exhausted talent that remains so productive? Perhaps it is the reader, or the listener, or the critic, who is exhausted, even embarrassed, and their response is evidence of a cultural unreadiness, or inability, to accommodate those compulsive artists who are, as V.S. Pritchett wrote of Dickens’s characters, ‘solitaries … caught living in a world of their own’, whose inner life is ‘hanging out, so to speak, on their tongues’.

Hornby doesn’t reflect on the ways in which his attachment has changed since 2016, but it seems unlikely that he would have written this book were Prince still alive. Much easier to write about two people when both of them are safely dead. It is only death that allows us to accept our heroes on their own terms, and extend our forgiveness.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.