The other day, I was talking to a man who was once the head of an Oxford college. He recalled an occasion in the late 1950s when he was a student himself and Kingsley Amis had come to address his college’s literary society. When Amis eventually asked for questions, a young woman said something that came as a surprise. ‘Can you give us your “Sex Life in Ancient Rome” face?’ she asked. (Jim Dixon, the hero of Lucky Jim, is keen on making faces, and is stumped at the end of the book because he is more or less happy, and so, ‘as a kind of token, he made his Sex Life in Ancient Rome face.’) Amis, suddenly befuddled, didn’t quite know what to say and the audience laughed.*

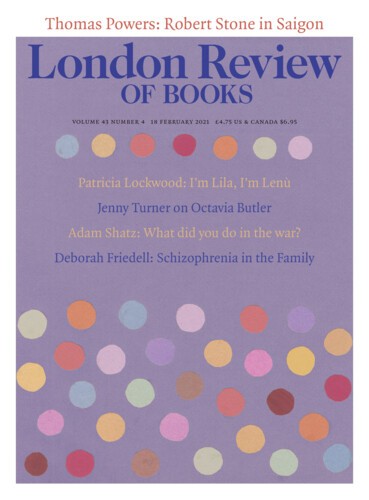

The young woman was Mary-Kay Wilmers. After working at Faber & Faber, the Listener and the TLS, she became one of the founders of this paper in 1979, and has just retired after more than thirty years as its editor. I wanted to begin with one of her jokes, an early one, because her gift for amusement has always been there, a crucial element in a career of giving life to arguments. Alan Bennett, a friend of hers since Oxford, gives an account of a posh dinner she once attended with her then fiancé, Tim Binyon. A flunkey at the door asked for their names so that he could announce them. ‘Paralysed with shyness,’ Bennett writes, Mary-Kay ‘told him it didn’t matter (and may even have said that she didn’t matter). Tiresomely, this gilded fly persisted, still wanting her name. “Oh, skip it,” she snapped, whereupon the flunkey announced: “Mr Timothy Binyon and Miss Skippit.”’ The wish to be noticed and not noticed (and noticed as being unnoticed) would remain with her, and it was fundamental to her talent as an editor. She was present and not present in every text published under her editorship. She was in her office, surrounded by her colleagues, creating a democracy of sorts, but also a sovereignty. Yet her claim to the throne lay not in any divine right to rule, but in the fact that she was the sharpest editor of her generation and the funniest. However hard, high-pressured or controversial, her work never precluded jokes. Such and such a man was ‘on a fault-finding mission’. ‘Marriages end,’ she said to Michael Neve, ‘but divorces never do,’ which Neve said was as Wildean as it gets.

It was J.D. Salinger, writing about William Shawn, who spoke of that rare thing, ‘born great artist-editors’, lovers of ‘the long shot’. I’ve admired a few editors, become their friends, holidayed with them and edited them back, fought for them, and put up with their grievances, as they’ve put up with mine. What you want in the end is a spirit guide, someone who knows what you can do, and takes pains alongside you. For Hilary Mantel,

Mary-Kay has come for me to be one of the small shadowy group of ideal readers I think most writers have lurking, somewhere at the back of their minds, when they sit down to write. These watchers in the psyche are more important than almost anyone else in a writer’s life because you depend on them not only for their judgment but also for the confidence they impart. They are shadowy because they hold the secret of your potential.

It’s not always easy to define an editor’s style, but Mary-Kay definitely has one. It relies on an enduring respect for the possibilities of ambivalence – ‘most writers believe too much in what they believe,’ she once told me – as well as what John Lanchester once identified as a ‘Russian horror of clarity’. It’s not that she doesn’t like clear prose, it’s just that she prefers it when writers don’t use that prose to know, in advance of knowing, what they think about everything, or to preach to the readers, or to make a show of their own honour. Before mansplaining was a thing, it was a thing to her, and she has cut enough platitudes from pieces, these forty years or more, to fill the offices of the Royal Society of Literature. The paper cuts any sentences that could be used as quotes on the back of a book. ‘Those are never good sentences,’ Mary-Kay said, when asked whether this policy was a bit hard on the praise-starved subjects of the reviews. She is the first to see the deficiencies in the paper she has edited, and wants more for it; she is always searching for better writers, better arguments, better jokes. She has always been an editor of independent mind, investing her hopes not in fashionable causes or political parties, not in closed belief systems or irrefutable language, but in the writers she has published.

Some people are orderly – to the point of disorder, obsessive-compulsively – and other people are disorderly in a productive way. Mary-Kay is in the latter class, good at appointments (hair, board meetings, eye drops) but not so hot on deadlines or at keeping her desk tidy. I once turned up at her house with a very long piece I’d been working on for months. For some reason, I couldn’t get the page numbering to work, so when she dropped the manuscript on the floor I nearly had a heart attack. She simply laughed, and said she’d work it out later. I knew then that we would never be married. Mary-Kay can endure any amount of doubt, and part of ‘the happiness of getting it down right’, as William Maxwell put it, may have lain for her in the mystery of not knowing exactly how she would do it. The spirit of Miss Skippit is alive in those moments, a certain coolness in the face of the unknowable.

She taught a generation of us that the job was to have a point of view. Vagueness wasn’t a useful quality, and grand declarations are not the same as good writing. If the paper didn’t capture certain points of view, it was, in Mary-Kay’s opinion, because we were still looking for the writer. Her editing is like her, unobtrusive yet characterful, yet her certainties – apart from those about the classical roots of English grammar – are always open to being challenged. ‘Nothing bothers her much,’ her children’s former nanny, the author Nina Stibbe, wrote. ‘Except she can’t stand having too much milk in the fridge (they have skimmed).’ Mary-Kay once wrote a sign that was taped above the tea station at the paper’s old offices in Tavistock Square. ‘Please wash your cup,’ it said. ‘There’s nobody who doesn’t resent doing other people’s washing-up.’ When Karl Miller saw the sign, he laughed and asked whether she was responsible for its ‘Johnsonian cadences’. If you want a manifesto of an editor’s style, just read those sentences again. In them you will find the LRB’s ideal tone.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.