At a certain point in my reading life, aged 12 or 13, I promoted myself to the adult section of my local library, climbing up three wide steps covered in yellow linoleum. There, not knowing how to choose, I gravitated to Elizabeth Bowen – along with others, including Compton Mackenzie and Hugh Walpole, of whose writing I can’t now recall even the faintest flavour. I’d never heard of any of them – I’d not heard of anybody much – but I was reassured by bound sets of collected works, because in the children’s section I’d been sustained by the endless seeming supply of Swallows and Amazons and Anne of Green Gables. And I liked the woodcuts by Joan Hassall used on each Bowen volume, which – though I still like them very much – I can now see are a few shades more sentimental and simplifying than the words inside. (Bowen in a 1968 letter to William Plomer at Cape: ‘Neither do I want any more of Miss Joan Cassell [sic].’)

I read my way through quite a few of Bowen’s books, and when I finished I hardly knew what had happened in them. Her prose was sophisticated, her references depended on all kinds of knowledge I didn’t have: this writing was not addressed to me, but over my head. Who were these people and what did they want, what did it all mean, why did they dress for dinner? What was it about Ireland anyway? And yet I loved this writing: it excited me and made its mark on me. It seems strange that you can love what you barely understand – but childhood consists of such foggy intimations and yearnings upwards. I loved the furniture in Bowen, the thickness of her detail and its coloured, textured specificity. No doubt I was drawn to the posh pastness of her contemporary world; I would have relished, for instance, the ‘crisp white skirts and transparent blouses clotted with white flowers; ribbons, threaded through’ on the first page of The Last September. (Needless to say, this was nothing like my life.)

And there was something so spiky in her sentences. The chunky solidity of her words and her difficult word order resisted any skimming along the top of apprehension. I felt the force of her ironies aesthetically, even if I couldn’t altogether follow them. Lois ‘stood at the top of the steps looking cool and fresh; she knew how fresh she must look, like other young girls.’ What was unobvious in Bowen’s prose held out a promise, even as it frustrated my efforts at comprehension: it seemed to say that nothing was, after all, obvious – everything was interesting, because complicated. Needing this to be true, I leaped at it. Now, that uncomprehending reading, at sea in a bright scatter of words and things and half-grasped insights – soon after, I had the same experience with Henry James’s What Maisie Knew, chosen because of the Degas on the cover – seems to me the pattern of most readerly initiations. We aren’t drawn in by the argument, or what’s said or shown. Rather something feels right, smells right, in the colour and flavour of the work.

So Bowen was one of my writers, at the beginning of my adult education. And then I forgot her for a while: she wasn’t in Leavis’s Great Tradition, and wasn’t on the Eng. Lit. curriculum in my university in the mid-1970s (she died, though I wasn’t aware of it, in 1973, aged 74). No one mentioned her name. The literary world was on the brink, in fact, of its great feminist reappraisal of 20th-century women writers – and Virago – but I was slow to notice. Bowen was probably one of my mistakes, I thought, like Anne of Green Gables or Compton Mackenzie. It was long after I’d left university that I became curious to seek out again what I’d once cared for, to see what it was worth; I began rereading Bowen in my thirties, when my reading horizons had widened in every direction and I was trying and failing to write myself. Now I’ve never not got something of hers open on my desk. As the years of reading and becoming pass, an inner family of writers assembles itself in your imagination. There’s the wide outward connection with a whole constellation of books: and then there’s this other, more intimate thing, more prejudiced and visceral. It feels like an elective kinship: there’s almost a blurring between your own sensations, and impressions and self, and those of these writers. (Writers, incidentally, get no say in being elected to the inner family: you can imagine the dismay of the great dead at finding themselves so adored, and by such adorers. But publishing is also a relinquishment: you don’t get to choose who reads you, or who feels with your words.)

Everyman recently reissued Bowen’s short stories in one of their gorgeous hardback volumes: it’s the same collection that was published by Cape in 1980, and then by Penguin and Vintage, except with a new, enthusiastic introduction by John Banville and a useful short bibliography. Bowen is one of those rare writers who is equally good at novels and short stories; in fact, because her novels are short, densely written, formally deliberate, it’s not easy to particularise any difference between them and the stories, apart from the obvious length and development. In her style and way of seeing, she’s a short writer: less rather than more, concision rather than expansion. She herself makes the best distinction between her novels and stories, describing ‘the steadying influence of the novel, with its calmer, stricter, more orthodox demands’. Into the novel, she writes, ‘goes such taste as I have for rational behaviour and social portraiture. The short story, as I see it to be, allows for what is crazy about humanity: obstinacies, inordinate heroisms, “immortal longings”’.

The description is characteristic as well as insightful. On the one hand, there’s her forceful authority, the economy and decisiveness in her summing up; on the other, there’s the romantic excess confessed to – immortal longings are in quotation marks because they’re both immortal and funny. The overreach of the imagination and the containment of a strong intelligence are inseparable. And no doubt those polarities derive in part from her class and her history: the dryness and smartness from an upper-class style, the excess from a long tradition of Irish Protestant gothic, as well as from her own experience.

Bowen was an only child, born in 1899 in Dublin where her father worked as a lawyer for the Land Commission, but with Protestant Ascendancy roots in a big plain rectangular 18th-century house in County Cork, on land that was granted to Bowen ancestors in the Cromwellian settlement. (She tells her ancestors’ story with finely judged generosity and criticism in Bowen’s Court.) Her father had a breakdown when she was seven and suffered episodes of mania; doctors advised that her mother move with Elizabeth to England, where they lived in seaside towns in the South-East, and she gained the vantage point of exile; nothing could seem more exotic, she reflected, to a child brought up amid the symmetries of Georgian Ireland, than the rambling villas of Kent, with their inglenooks and ornate porches, their ‘bow windows as protuberant as balloons’. ‘What had to be bitten on,’ she wrote, ‘was that two entities so opposed, so irreconcilable in climate, character and intention, as Folkestone and Dublin should exist simultaneously, and be operative, in the same lifetime, particularly my own.’ Then, when Bowen was 13, her mother died of cancer. Boarding school with its impersonal regularities was a refuge from grief and chaos.

Bowen published her first collection of stories, Encounters, in 1923, when she was 24; that year she also married Alan Cameron, who worked first in education and then in schools’ broadcasting for the BBC. The marriage worked – Bowen liked making a home, and entertaining – and lasted as a fond childless companionship (though she had passionate love affairs) until Alan’s death in 1952. They lived in Northampton and Oxford, then eventually in Clarence Terrace near Regent’s Park, spending what time they could at Bowen’s Court in County Cork. After Alan died Bowen eventually realised, with great regret, that she couldn’t afford to keep up Bowen’s Court, and sold it to a local farmer, who assured her he would move his family there, but then demolished it and cut down the timber. She spent her last years in Hythe, back on the Kentish coast.

From the very first stories, the writing is ambitious. And behind the working-out of plot – to begin with mostly satirical, keeping the faintly ridiculous characters at amused arm’s length – there’s place: place that’s more than place, place as being, laden with history and implications. First, she seems to want to catch in words a particular moment, in particular weather and light – sometimes outdoors, or, more often, surrounded by the right furniture, inside a particular house. In her first collection, these moments often dwarf the story’s actual content and point (Bowen herself called her early stories ‘a mixture of precocity and naivety’). In ‘The Confidante’, whose love entanglement is as neat and negligible as a card trick, ‘the room was dark with rain, and they heard the drip and rustle of leaves in the drinking garden. Through the open window the warm, wet air blew in on them, and a shimmer of rain was visible against the trees beyond.’ Bowen said she was trying ‘to make words do the work of line and colour’ and that she had ‘the painter’s sensitivity to light’.

The best story in the first collection is ‘The Return’, whose protagonist, Lydia, is a young and plain lady’s companion. She’s had the house to herself while her ghastly middle-aged employers, the Tottenhams, are away at a hydro; now they’re back and she can’t bear to give it up to them:

The hall outside was cold and quiet. The sense of the afternoon’s invasion had subsided from it like a storm. Through a strip of door the morning-room beckoned her with its associations of the last six weeks. She saw the tall uncurtained windows grey-white in the gloom.

Her book lay open on a table: she shut it with a sense of desolation.

In the rest of the story Bowen doesn’t close down the possibilities she’s opened up: neither in Lydia’s thwarted sensibility, nor – generously, unexpectedly – in Mrs Tottenham’s. Mrs Tottenham’s old lover has written to her: she rubs lipstick hopefully into her cheeks then, looking in the mirror, scrubs it off and burns his photograph. Lydia opens her imagination to the older woman’s history for the first time, and feels her own youth suddenly ‘hard and priggish and immature’. The recognition alters everything, ‘as though a child had been born in the house’.

In Bowen’s second collection, Ann Lee’s (there were to be seven collections in the end), she stakes out her terrain more boldly. The contained form and the mannered stylishness persist, along with the author’s all-seeing irony, set apart from her protagonists’; yet the work grows stranger, and more sympathetic. Bowen hadn’t read many short stories when she began to write her own: no ‘Hardy, Henry James, Maupassant or Katherine Mansfield’, Victoria Glendinning says in her 1977 biography: ‘she was not following any genre theoretically familiar to her.’ And for whatever reason, as she finds her way, it isn’t to drift Mansfield and Woolf style, avoiding closure or narrative certainty. Bowen’s stories don’t break the genre frame; rather, they swell it from the inside and make it strange. That’s her modernism. At this stage all her stories were still set in England, or in an England twisted round and made odd enough to be interesting. She plays up and down the range of the middle classes and into the gentry: nobody is impossibly lofty or titled (unless the title is Italian), though sometimes when she strays down the social hierarchy – into the new housing estates, say – there are strong whiffs of condescension.

There’s no condescension, however, in the title story, ‘Ann Lee’s,’ which is about a hat shop, though not just any hat shop. The milliner is a goddess in her feminine lair; the society ladies Mrs Dick Logan and Miss Ames are humble votaries permitted to enter, consumed by desire for the wonder worked by Ann Lee’s hats. The only man who ventures inside the shop – indifferent to hats, desperate for Ann herself – is horribly punished: he isn’t torn apart by his own hounds exactly, but passing the two ladies afterwards in the street he ‘went by them blindly; his breath sobbed and panted … they knew how terrible it had been – terrible.’ The story is comic; it’s conventionally funny to invert the usual scale of importance and treat these women’s belief in the hats’ power to transform them (despite Mrs Logan’s dread of her husband’s wrath over the bills on quarter day) as if it were religious belief or sacred ritual. And it is funny: ‘These were the hats one dreamed about – no, even in a dream one had never directly beheld them; they glimmered rather on the margin of one’s dreams.’ But being funny doesn’t mean it isn’t also dealing with the sacred. Outside the frame of the story Dick Logan presides, with his disapproval and his control of the finances; inside its magic space, style is mystery and the women are initiates. This is Bowen’s way of imagining how a terrain is gendered: what feels masculine in her authority – her tone, her control – enables in effect an upending of hierarchy, opens up a wild female space of the absurd, the inadmissible, which isn’t sentimentalised, because of the tone, the control.

It’s on those absurd female intimations – obstinacies, inordinate heroisms, ‘immortal longings’ – that the meanings of her stories begin to turn. In ‘The Parrot’, Eleanor, a repressed young paid companion, chases her mistress’s wretched escaped parrot into a garden several houses along, where the arty Lennicotts entertain, to the outrage of their neighbours: the headlamps of the Lennicotts’ visitors’ cars lend ‘an unseemly publicity to the comings and goings of everybody’s cats’. Eleanor ends up on the roof with Mr Lennicott, who writes improper novels and wears a dressing gown embroidered with dragons, but turns out to be amiably game for parrot-chasing. ‘A girl like you,’ he says, ‘ought to be able to climb like a cat.’ Then:

He gripped both her hands and hoisted. He was sitting astride the roof, and Eleanor sat side-saddle, tucking down her skirts around her legs. White clouds had come up and bowled past before the wind like puff-balls; the poplars swayed confidentially towards one another, then swayed apart in mirth. One of the Philpot girls was mending a bicycle down in their garden, but she did not look up. Her bowed back looked narrow and virginal; Eleanor half-laughed elatedly.

In ‘Joining Charles’, from the third collection, Charles’s disenchanted young wife stays with her husband’s mother and sisters before setting off to meet him in their new home in France. She falls in love with the women’s gentle domesticity, which is devoted to supporting their idea of Charles as everything he actually isn’t: ‘generous, sensitive, gallant and shrewd’. (In a gothic touch, Polyphemus the cat knows better: Charles put out its eye.) The entanglement of desire and constraint is intractable: if Mrs Charles were to break with the whole frame of his family’s belief, and declare that she didn’t love him – as surely eventually she must? – she would lose everything, couldn’t be connected to them any longer. (And are Charles’s women able to be innocent because he’s awful on their behalf? Just as, after all, Dick Logan earns the money his wife spends on hats.)

Bowen’s children are especially good, and more at home than the adults with intimations of the inadmissible. Roger in ‘The Visitor’ is staying with two maiden ladies, and waiting for news of his dying mother, whom nobody mentions. When the early morning sun washes over the garden, the shadows in the strange bedroom make him feel, luxuriating in the sensation, ‘as though he were a young calf being driven to market netted down in a cart’. In ‘The Jungle’, girls negotiate their friendships around the delicately cruel etiquette of boarding school; in a beautiful culminating scene, Rachel and Elise escape into a patch of wild ground just beyond the school boundaries. Tramps have left rags in the bushes there, and Rachel is afraid of dead cats, but when Elise wants to lie in Rachel’s lap a realm of irresponsible pleasure becomes real. Bowen’s literary worldview is distinctive among English-language ironists in the mid-20th century, partly because in her imagination (as in late James, though not in Woolf or Mansfield) love’s object may be worthy, and consummation isn’t only for dreams. There’s always irony, but there’s also always more than irony:

‘I say, Rachel, I tell you a thing we might do –’ …

Rachel wound herself up in her muffler by way of a protest. She had a funny feeling, a dancing-about of the thoughts; she would do anything, anything. ‘’Pends what,’ she said guardedly.

‘You could turn round and round till you’re really comfy, then I could turn round and put my head on your knee, then I could go to sleep again.’

As she chronicles the Home Front in the Second World War, the extreme distortions of wartime correspond to an extremity in Bowen’s vision; she makes vivid in her fiction ‘the thinning of the membrane between the this and the that’ and the invisible presence of the dead, ‘who continued to move in shoals through the city day, pervading everything to be seen or heard or felt with their torn-off senses’. In ‘Mysterious Kôr’, lovers under a bombers’ moon search in vain for somewhere they can embrace unseen; in ‘Ivy Gripped the Steps’, a soldier revisits in wartime a privileged house on the south coast where he was betrayed as a child – it’s shut up and overgrown now, behind barbed-wire defences. Bowen was an air-raid warden in London and stayed in her Regent’s Park house until it was bombed; when she went to Ireland she sent confidential reports on morale to the British Ministry of Information, though Roy Foster says she was ‘warmly defending neutrality’ in them, ‘as an Irishwoman’. Foster has persuasively made the case for Bowen’s thoroughgoing Irishness – ‘as long as I can remember,’ she wrote, ‘I’ve been intensely conscious of being Irish.’ Her work, Foster says, is always shot through with the characteristics of the Irish literary tradition: its ‘sensuous language, baroque humour … uncanny ability to recreate childhood, and a sense of place experienced with a paranormal intensity.’

There’s more of Ireland proportionately in the novels than in the short stories, and yet the Irish stories are among her very best, particularly the long ‘Summer Night’, ripe with the disruptive magic of a midsummer night’s dream. A young woman, Emma, is driving as the sun sets – ‘its light slowly melted the landscape, till everything was made of fire and glass’ – away from her husband and children, to spend the night with her lover, Robinson, a factory owner in a provincial town. When she stops at a hotel to make some telephone calls, everyone is away at the dog races: it’s wartime in England and the reverberating absence echoes the eerily suspended state of Ireland, while according to the newspaper headlines ‘an awful battle’ rages elsewhere. The story sprawls across distances (though in time it’s tightly chronological), yet all its elements feel marvellously, mysteriously linked: Emma’s left-behind daughter, Vivie, bouncing on the bed and painting her naked body with schoolroom chalks; Emma’s husband’s inhibited forbearance and the cramped malevolence of his old aunt; Robinson’s friends, the intelligentsia of the small town, who have unfortunately chosen this same evening to make their social call: Queenie, a beautiful deaf woman, and her clever troubled brother, who is in love with Robinson.

The enigmatic Robinson, ‘big, fair, smiling, off-hand’, seems to stand for new Irish possibilities, with his charisma, his pragmatism, his all-electric kitchen and his straightforward bluntness. Emma, a product of her Anglo-Irish heritage – her husband is a major and listens to the war on the wireless; her cook works in a kitchen that’s all ‘blacklead and smoke and hooks’ – wants agonised adulterous romance, a ‘ruin, a lake’. Robinson is impatient for her to ‘come out of that flowerbed’ and inside his house; she’s frightened of his ‘stern, experienced delicacy on the subject of love’. ‘But have I been wrong to come?’ she asks, all sensibility. ‘That’s for you to say, my dear girl … You have got a nerve, but I love that. You’re with me. Aren’t you with me?’ Sexual love isn’t a dream, it’s for real beds not flowerbeds, and in truth Emma has had enough of her romantic major, with his defeated decency. And yet, because this story spreads everywhere, its last word goes to Queenie, dreaming of the ruin and the lake.

Bowen wrote fewer short stories in her last decades, while she was working on her strange, late novels. She had begun to seem old-fashioned, her stylishness belonging to another era, her perceptions no longer quite mapping onto contemporary experience. But now, fifty years after her death, when the 1960s are past history too, we can do justice to her achievement: it can seem as fresh to us, or fresher, than writing that was in its moment more fashionably avant-garde. I think – but then I’m prejudiced – that she’s as good as anyone: better than Woolf, who’s enshrined at the heart of the canon. Bowen is more confidently passionate, without Woolf’s debilitating doubt; her apprehension is more acute; she’s funnier; the flow of her words is more elegantly sure and more original.

The first editors of this collection of her stories chose wisely to end it with ‘A Day in the Dark’ from 1956, a wonderful scrap of an Irish story about the despoiling of a young girl’s first love, which seems to look forward to Edna O’Brien or Claire Keegan. Barbie is living one summer with her uncle, in a sensual dream of happiness, in love with him without knowing it. He sends her to pay a visit to his neighbour, a thwarted, fascinating, clever woman his own age, who also wants him; in a few cruel words she awakens Barbie from unknowing. Here, in its last leaping, throwaway sentences, so lightly managed, in such a perfect conjunction of form and meaning, freedom opens up exhilaratingly in the reader’s imagination even as poor Barbie, disabused, steps back presumably inside the story of the rest of her life:

At the same time, my uncle appeared in the porch. He tossed a cigarette away, put the hand in a pocket and stood there under the gold lettering. He was not a lord, only a landowner. Facing Moher, he was all carriage and colouring: he wore his life like he wore his coat – though, now he was finished with the hotel, a light hint of melancholy settled down on him. He was not looking for me until he saw me.

We met at his car. He asked: ‘How was she, the old terror?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘She didn’t eat you?’

‘No,’ I said, shaking my head.

‘Or send me another magazine?’

‘No, not this time.’

‘Thank God.’

He opened the car door and touched my elbow, reminding me to get in.

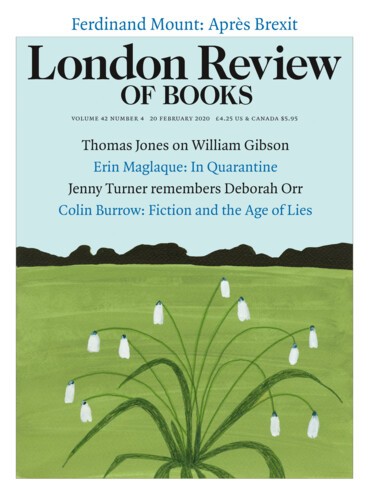

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.