In the spring of 1942, Elisabeth Young, a diplomat’s wife living in Surrey, began keeping a ‘register’ of eggs. Each day, she recorded the date and number of eggs laid by her flock of 12 hens, sometimes logging the name of the particular hen who had laid it. She noted whether the eggs were brown or white or ‘brownish’ and any that were double-yolked. At the end of the week, she tallied up the total. She also made a note of hens that were broody and the ones that were moulting. When the very first hen laid its first egg, Young recorded the event not just in the register but in her diary. ‘An active day – but culminating in the breathtaking event of the FIRST EGG!’ Over the course of the next year, Young went on to record 896 more eggs in her register, each one written down in her neat hand in geometrically exact columns.

Few people, even poultry keepers, would have the energy or inclination to keep such close track of a hen’s laying patterns, but we all have our own versions of an egg list. It’s a rare person who doesn’t use lists of one kind or another as a prop to give themselves the illusion of maintaining order over things. We construct shopping lists and guest lists and reading lists; lists of the hundred greatest songs and lists of things we plan to do one day – the to-do list that never quite gets done. Others, like the list of eggs, are stock-keeping exercises: taking the measure of our gold. This kind of listmaking is coming back into vogue among millennials with the rise of ‘journaling’: a habit of listing the good things that have happened during the day as a way of improving mental health. In wartime Britain, the fresh eggs that Young logged so meticulously were a rare and valuable commodity. In the shops eggs were rationed to one per adult per week, a ration which poultry keepers could exchange for chicken feed coupons, so what Young was writing down was a kind of riches. ‘30 March. No. of eggs. 2. Brown, White’.

Young was 26 when she was drawing up her egg log and recovering from postnatal depression after the birth of her first child and pregnant with her second. She and her husband, Gerry, were staying with her husband’s sister in a country house called Little Oaks to avoid the German bombs in London. Young was an unsettled person in unsettled times. The year before, her older brother, Norton, who was almost certainly gay and suffering from anorexia, had killed himself. Norton, who worked in Oxford at the Bodleian Library, once wrote to his sister that ‘life isn’t all powder and undies, as Shakespeare said.’ Norton referred to himself as a girl in a letter to Elisabeth and there were rumours of a conflict with his father, perhaps over his sexuality. In March 1941, he climbed into an empty bathtub, covered himself with an overcoat and swallowed a lethal dose of chloral hydrate and bromide – sedatives prescribed for insomnia. He had addressed a stilted suicide note to his father, a diplomat like Elisabeth’s husband: ‘I am shortly going to take as much of my accumulated dose of sleeping draught as I can manage and hope that it will prove lethal. You know the reasons, food shortages and increasing debility and weariness – unlikeliness of us winning the war etc. etc.’

When the news came through of Norton’s death, Elisabeth’s parents, who were in Ankara, sent a telegram to her younger sister Alethea, who was travelling with friends in India. It read: NORTON DIED SUDDENLY BURIAL MEREVALE DO NOT CHANGE PLANS. Neither of Norton’s parents returned to England for his funeral; they cut his image out of family photographs and didn’t speak of him in public.

After her brother’s death, Elisabeth, who was the only family member in the country, did the one thing she could and made a list. It was a list of ‘Norton’s Things’ to be put in storage. It is written in the same neat black hand in which she wrote her Egg Register and it begins:

1. Mahogany dressing-table with glass top.

2.&3. " loose-seat chairs.

4.&19. " Book-case: (tall, two pieces; cupboard at bottom full of note-books, maps, photograph albums etc.)

5.&6. " Cases of books.

7. Brown trunk. 8.* Black trunk

9. Mahogany 2-flap table. (Large; dining-room size)

10. Gramophone records.

* Sent to Aunt Joyce, full of clothes.

When Norton took the overdose he had just arrived home with Elisabeth after a trip to Warwickshire to visit relatives. He never unpacked his clothes from the trip. After his death, this packed suitcase became just one more item on the list of ‘Norton’s Things’. The list, like all lists, had omissions. It didn’t include Norton’s favourite pink dressing gown, for example, though that may have been among the clothes in the trunk sent to Aunt Joyce.

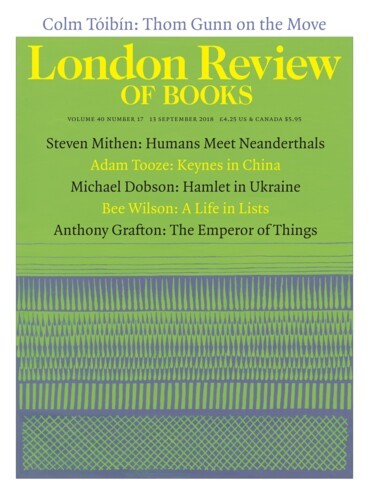

Elisabeth’s granddaughter, Lulah Ellender, has decided to tell the story of Elisabeth’s life through the lists she kept between the years 1939 and 1957. Ellender never knew her grandmother: she died of cancer when Ellender’s mother was just nine. The book, Ellender explains, ‘grew out of a moment’ when her mother handed her a small marbled journal that had belonged to her own mother. She opened it and found ‘pages and pages of lists’; effectively, ‘a glimpse of her life in fragments and scraps’. Ellender pieced together information from the lists and Elisabeth’s diaries and letters to build up a picture of a relatively short, privileged life characterised by ‘movement and displacement’ but also by ‘strict protocols and complex systems of etiquette’ in which lists could act as shields against frightening emotions. A perceptive and original first book, it is as much a meditation on the meaning of lists as it is a biography. In and of itself, the life of Elisabeth Young was not particularly noteworthy. Apart from the travel to far-off places, she led a fairly conventional upper-middle-class life of home-making and diplomatic drinks parties. She was said by those who knew her to be a beautiful woman with an infectious laugh and a collection of couture dresses, including one by Dior made of pale gold silk. But it is the lists that create the fascination. ‘A list provides a purpose and a structure,’ Ellender writes. At ‘its most basic, it can be a guide to how we should use our time; at its most profound, a means to lasso our grief, madness and dreams within neat lines.’

Elisabeth was born in 1915. She and Norton and their sister, Alethea, spent much of their childhood at boarding schools in England while her father, Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen, was posted to various locations overseas. The children would join their parents in the school holidays: Brussels in 1921, Paris in 1923, Latvia in 1930 and Persia in 1934. Knatchbull-Hugessen is now chiefly remembered as the buffoonish ambassador to Turkey during the Second World War who didn’t notice that his valet, Elyesa Bazna, was regularly opening his mail and his safe and passing the details on to the Germans. This became known as the Cicero Affair (the valet’s codename was Cicero). In Knatchbull-Hugessen’s obituary, the Times noted that ‘it is proof of the high regard felt in the Foreign Office for Hugessen that this strange affair did not affect his career.’ His was a mind, the obituary went on, that ‘instinctively eschewed complexities and so saved him from the pitfalls which, especially in dealings with clever foreigners, beset the path of the over-ingenious intellectual’.

In 1936, when Elisabeth was 21, her father took up the post of British ambassador to China and the whole family joined him first in Peking and then in Nanking (now Nanjing). They were there in the months leading up to the Nanjing massacre of 1937-38, when the Japanese captured the city and killed somewhere between 50,000 and 300,000 people (the number is still disputed). But within the British community in the Legation Quarter, life centred on tennis and riding and parties and nights of drunken golf played with glasses and bottles instead of clubs and balls. In one letter, Elisabeth asks to be sent some goldfish bowls instead of the waffle-irons she had originally requested, because she wanted to drink brandy from them. One night, she found herself at a party at the embassy where, suddenly, everyone decided to break gramophone records over one another’s heads, for a lark.

It was in China among the embassy set that Elisabeth met her future husband, George (‘Gerry’) Peregrine Young, who was as keen on tennis as she was. A group of British people were out riding one day in February 1937 near the Purple Mountains outside Nanking when Elisabeth heard a whizzing sound and felt something hit her forehead. It was a bullet. Gerry leaped down from his horse and used a door key to extricate it from Elisabeth’s head. It isn’t clear who fired the shot, or why. In July 1937, as hostilities built up between Japan and China, Elisabeth’s father’s car was bombed by a Japanese plane on a trip from Nanking to Shanghai. He was knocked unconscious but survived. At the end of 1937, the family returned to Eaton Place, just in time to avoid the massacre. The following year, Gerry and Elisabeth became engaged. He proposed by phone. She replied by letter: ‘Tonight. Just before going to sleep. Yes, I am drawn towards the idea of marrying you. Forsooth a capital plan. Darling Gerry, it will be so perfect. I know it will, and I’ve never known anything was perfect before – tra, tra-la-di-diddle.’

They married just before war broke out in 1939 and WEDDING PRESENTS was the first list Elisabeth recorded in her book. The presents given to her and Gerry included a sewing machine, a brooch, seven greenish champagne glasses, a picnic basket, a fireguard, a watch ring, a wooden tray, orchids from the Turkish ambassador, six separate early-morning tea sets, a triple mirror, a mustard pot, a pearl necklace from ‘Grandpapa’, a cheque for £25 from Lady Brabourne, a tablecloth and more. She noted the date the presents were received and the names of the present-givers, from Lady Sligo to Nanny.

One of the thoughts the book gives rise to is just how many belongings would have been acquired and husbanded in the course of a posh existence in the early to mid-20th century. After marrying, Elisabeth and Gerry set up house together in a flat in Holland Park and she began a series of lists of things they needed. She made lists with curly brackets telling herself to sort out the flowers, the accounts, the oddments, the floor, to rearrange the bookcase and ‘Re-sort things’. And then she made another list called ‘Still wanted for flat’, which included eiderdown, potpourri, cigarette case, backgammon, small table, hotplate.

‘List everything,’ reads an instruction to herself on one of Elisabeth’s lists. Ellender sees her grandmother’s incessant listmaking as a coping mechanism. She was a woman ‘organising the small things of life as if gathering in a clutch of slippery fish’. When pregnant with her first child, she made a list called ‘Things for Samuel-Susan’, allowing for the two alternative futures. The list included a cradle, a Moses basket, Vaseline, Mackintosh sheets, four Viyella dresses, one big Shetland shawl, a bath, scales, a pram, safety pins, a hot water bottle, Dettol and baby soap. ‘The brain craves completion,’ Ellender writes, ‘and a list provides a solution.’ Ellender sees this baby list as an outpouring of hope on the page, or a ‘letter to a future self. We have to visualise a self that is well, happy, functioning, a self free from shame, a self performing its tasks efficiently and happily.’ The self that exists in the list may be nothing like the person who writes it.

After the birth of the baby – who turned out to be Samuel – Elisabeth found herself crying all the time, living in a rented house in Surrey, Warren Farm. She recorded one day in her diary that ‘it rained & Samuel seemed to be crying more than usual, & I got worried, & we couldn’t get his nappies dry, & Patterson [the housekeeper] complained about the stove & couldn’t keep the water hot. Oh dear – I did so want to get it all going properly.’ Another day, she wrote: ‘I hope I feel different soon, I can’t stand this unreasonable depression.’ There are situations that even Dettol can’t fix. Gerry and Elisabeth decided to move out of Warren Farm to Little Oaks, the house where she kept the eggs. She wrote a list: ‘Things taken from Warren Farm’.

In 1944, Gerry was posted overseas again, to Beirut. He flew ahead and Elisabeth and their two sons followed once their belongings were packed. Among others, she made a two-page list of pieces of china that would be either transported to Beirut or stored at home for their return. She also listed all the clothes that the family would need for Beirut and the estimated cost of shipping, including five guineas for Gerry’s ‘undies’. For Samuel and Charles, her two boys, there would be jumpers and socks and summer coats. For ‘Me’ she listed:

Linen coat & skirt 18 gns Flowered afternoon dress

(made up, Fn. silk)13 gns Flowered chiffon, made up 5 gns Chinese satin, made up 9 gns 1 less smart A-dress 4 gns 2 more cottons 4 gns Hats? Yellow, Black straw

Gloves3 gns Stockings 3 gns 2 good blouses 6 gns Slacks 2 gns Shorts 1 gn Sports shirts, 2 1 gn 2 Jumpers 3 gns 2 good wool dresses 20 gns Shoes, 2 prs 4 gns

From this list of clothes, we can imagine the embassy parties that Elisabeth attended in Beirut: the women in their afternoon dresses, the men in their suits. ‘We sweated away, attending gymkhanas, race meetings, sports etc,’ she recorded in her diary. She also used her list book to record the food she would serve at her cocktail parties, for example:

1 Cold Cooked Turkey

2 Tin Spam

½ Kilo Ham

40 Crab Patties (2 tins crawfish)

2 Large mousses of tongue

1 Bowl Russian salad, 1 bowl cabbage salad

60 Bread rolls

There is something brittle and dispiriting about this list. It is the food of chit-chat and empty show. Wherever they travelled in the world, the wives of British ambassadors transported their tins of Spam, their martinis and their flowered chiffon dresses. They were obliged to maintain a good façade at all times, and to be amusing. On an earlier posting to Madrid, in 1940, before the children were born, Gerry wrote to his mother that ‘Poor E. is wretched. I never see her except at meals or in bed; and the meals are always parties, and by bedtime – 2.30 a.m., usually – we are both too tired to make sense.’

For Ellender , reading her grandmother’s lists is ‘a way of conjuring out of the dust and ink a person I never knew’. She argues that the lists Elisabeth made are ‘almost works of art, existing as simple, pared-down expressions of her spirit’. This is claiming both too much for them and too little. What is most fascinating about the lists – and the book that Ellender has constructed out of them – is not that they reveal the workings of one woman’s mind so much as the way they exemplify a set of social norms shared across a whole stratum of British life in the 20th century. They are dispatches from the inner workings of the British establishment. Elisabeth’s wedding presents make us think of all the other lists of wedding presents on which so many thousands of posh British families were founded both in Britain and abroad: the generic cabinets of silver and china, the mustard pots and fish forks, the coffee spoons and mahogany tables. There is a common language to these objects. Everyone in Elisabeth’s world knew what a ‘good wool dress’ looked like, just as they knew a man could prove his mettle by showing an interest in cricket and tennis. On one of his first postings Gerry wrote to his parents: ‘If you could … let me have a dozen good tennis balls, my chance of finding out how things are here would be much improved.’

It’s said that we can understand the core values of a tribe from its relationship with objects. This is a book about a class of relatively rich people in a deeply hierarchical milieu – that of the British Foreign Office – who were both elevated and enslaved by the things they owned. Elisabeth’s tablecloths and greenish champagne glasses and pearl necklaces and small tables were what gave her family distinction and a sense of home. As she travelled – to London, Nanking, Madrid, Surrey, Beirut, Rio, Berkshire, Paris and then, finally, London again – her belongings helped her to belong. But the management of these objects, which fell to her, as to so many other women, was also mentally exhausting. She was not yet living in the fully consumerist society we occupy now, where if one of your possessions no longer pleases you it can go to a charity shop or the tip. Every time the Youngs travelled to a new country they took the same refrigerator. The stuff Elisabeth listed so carefully was seen as valuable, and owning it was not just a privilege but a burden. There was so much to keep track of, all the more so given how often she and Gerry moved around. When they first set up house together in Holland Park, she made a list of furniture in storage, including one eiderdown, a small walnut bureau, a large square settee, a three-foot mahogany hall table, two Persian carpets and two Turkish ones. In a family where self-expression was censored – as Norton’s example shows – making a list and writing it down was a safe form of creative writing.

There were times when Elisabeth Young was in optimistic mode, counting her eggs or taking stock of the furniture. ‘The hens have laid 37 eggs this week,’ she recorded in her diary in 1942. But there were other times when the chaos of life made a mockery of her lists. In a diary entry made when she was living at Little Oaks she described the way ‘every now and then the work “got on top of me” & I felt absolutely dead. Which annoyed me, as so many people have to do as much & more all their lives.’ Compared to her prewar life, the disorder of Little Oaks drove her to despair. She couldn’t stand her brother-in-law’s table manners, or the ‘dirty butter dishes, stained tablecloths, beer bottles standing about everywhere’, or the ‘poultry making messes on the verandah’.

Folded in a box of letters, Ellender found a list that was different from all the others. It is called ‘Things That Worry Me’ and it starts:

My determination to find everything wrong

My inability to face anything

The trouble I give everyone

I don’t want to do anything

Isn’t it my own fault, & aren’t I letting it all become an attitude of mind?

… Money comes into it all the time.

Not quite sure what I do want, that is really attainable, that fits in a) with G b) possibility of going abroad

Anyway why should I have what I want?

I seem to have no control over my mind or moods

She suffered from serious episodes of depression all her life and often took to her bed for days at a time. To help with her mental torments, her doctor prescribed ‘pink pills’, which were really nothing but iron tablets. When Gerry was posted to Paris and she developed terminal bowel cancer at the age of 42, her friends at first assumed it was another bout of depression that took her from France to a nursing home in Wimbledon.

A list of worries is very different from a list of eggs or a list of cocktail snacks, but maybe it offers some of the same comforts for the person who makes it: allowing them to take the measure of things and create the sense that they are still in charge. I suddenly remembered a list I kept when I was ten years old and being viciously bullied at school, something I couldn’t tell my parents about. ‘What a pity you don’t play with those nice girls any longer,’ my mother sometimes said. But how can you play with someone who punches you and calls you names? In the evening, crying in my bedroom, I kept a list of friends and enemies. Depending on how the day had gone, I might cross someone off one list and transfer them to the other column. There was also a third category, which included most of the people I knew: ‘Not sure.’ The writing down of my uncertainty made it feel less uncertain.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.