This isn’t an essay about clothes, exactly, nor is it about fashion, quite. It is about women and clothes and something that happens between them that we could think of as a kind of third rail of female experience. I’ve thought about this for some time but my thoughts were focused when I saw Isabelle Huppert in Paul Verhoeven’s 2016 film, Elle. The film begins with a rape about which the victim, Huppert, is ambivalent. This sent the critics, particularly male critics, scuttling to and fro wondering whether it was a feminist, post-feminist or anti-feminist film, or just in some baffling way French. In the Guardian, Peter Bradshaw went for ‘provocative’, before deciding it was a ‘startlingly strange rape-revenge black comedy’. I didn’t think it was as strange as all that and I did think it was funny, but what really struck me was that every woman I knew who had seen it was mesmerised not by the ‘issues’ but by Huppert, and not just for her acting – she’s always good – but for what she wore: ‘the clothes’, women said to one another, were ‘amazing’. Yet when you look at them in stills they aren’t amazing, they are the epitome of French ready-to-wear chic. So if it wasn’t the clothes or the actor that created the effect, it was some compound of the two that created a character, a presence able to walk the tightrope that carries the film over the fire pit of sexual violence and women’s agency.

There are many less extreme instances in real life where women dress to create a particular effect that isn’t principally or at all about attracting men, though men often think it is. There is, for example, the iron rule that north of Derby no woman can wear tights on a night out. Why? How did Liz Hurley launch an entire career by wearing a dress much less extreme than many that Versace has shown on the catwalks of Milan? What happens when it goes wrong? Did Diana overdo it on Panorama? Why do Melania and Ivanka, on a trip to the Vatican, look more Gothic than Catholic? And at what point do we draw the line between dress and costume, between life and art? Edith Sitwell was made to feel self-conscious about her appearance as a child. As an adult she made sure that everyone else would be conscious of it too; this was dress as the performance of personality.

My thoughts about women and their clothes, how they wear them and also how they write about them, led me to Virginia Woolf and the term she coined: ‘frock consciousness’. On 6 January 1925, at the beginning of her diary for that year, she wrote: ‘I want to begin to describe my own sex.’ That thought recurs in the diary as the months go on and it is cast, increasingly, in terms of clothes. ‘My love of clothes interests me profoundly,’ she wrote. ‘Only it is not love; and what it is I must discover.’ This was the year Woolf published Mrs Dalloway, which brought her to literary prominence; the previous year she had sat for her photograph in Vogue. For that she chose to wear a dress of her mother’s, which was too big for her and long out of fashion. To plant it in the most famous fashion magazine in Europe was to make a statement, however ambiguous. And the experience of the sitting prompted a further thought: ‘My present reflection is that people have any number of states of consciousness: & I should like to investigate the party consciousness, the frock consciousness etc. These states are very difficult … I’m always coming back to it … Still I cannot get at what I mean.’ I don’t suppose that I shall get at it either, but I will revolve the question again and apply the advantage of nearly a century of hindsight to the idea of frock consciousness, an idea that I think was not born but at least much heightened in that period between the world wars just as Woolf was trying to put her finger on it.

If human character did, as she famously suggested, change in or about 1910, women’s clothes changed very soon afterwards. Another product of 1925 was the woman’s ‘pullover’. Not today the most exciting item in anyone’s wardrobe, it was in its way revolutionary. A pullover is pulled over the head both on and off and the person who does the pulling is the wearer. Yes, I know, but until then it had been, for more than a century, virtually impossible for a woman to get dressed – or undressed – by herself. The rich had ladies’ maids, the poor had one another, but the laces and hooks and eyes, the fastening behind, required assistance. This was not true for men. In the persisting convention that women’s clothes have buttons on the left, for the convenience of the average right-handed dresser, while men’s have them on the right, to suit themselves, there remains an archaeological trace, a fossil record, of the different history of women and men in their relation to their clothes. Fashion writers, who are apt to discuss new trends with the urgency of war reporters on a particularly dangerous front line and to misuse the word ‘iconic’ relentlessly, can be forgiven for idolising the Italian couturière Elsa Schiaparelli and her ‘cravat’ pullover. It stands for a new age in women’s clothes. Not only could you get in and out of it by yourself but the fiddly bits, the bow and ribbons, are knitted into the one piece. Schiaparelli, who was a surrealist and worked with Dalí, had made a satire, a cartoon of female dress.

Other events of 1925 included the Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs, from which the phrase ‘art deco’ was coined: a style that favoured angles, shadows and faceted planes, machine-turned, bevel-edged furniture and teapots on the slant, a style in which the machine age met the jazz age. This was perhaps the only period in which women who looked like Schiaparelli and Wallis Simpson, with their hefty, dynamic profiles, could have been leaders of fashion. Women were prominent in the world of haute couture between the wars. As well as Schiap, as she was known, there were Coco Chanel and Jeanne Lanvin. Schiaparelli’s sporty, dress-yourself look suited women of action. Amy Johnson, who flew solo to Australia, was one, and, in a rather different vein, Mae West in Every Day’s a Holiday. West – whose billowing curves billowed a little more at each fitting, causing the somewhat snappish couturière considerable annoyance – was in appearance the antithesis of the deco style. But she was straining the limits of more than Schiaparelli’s seams. She challenged the censors and the film studios, she talked about sex in ways that women in general were not supposed to and she took control of her films and her image in a way that actresses in particular never had.

Yet the ambition for independence and the claims to effectiveness are not simply reflected in the clothes: they are also to some extent created by them. Neither of these women was in herself what Schiaparelli’s designs made her. Johnson was unhappily married to a classic 1930s cad and on her famous flight to Brisbane in 1930 her de Havilland Gipsy Moth touched down, in the words of her biographer, ‘too fast and too late. She landed upside down in front of an excited crowd of twenty thousand’ – not, we may assume, looking quite unruffled. West, who wrote a lot of the script for Every Day’s a Holiday and took credit for all of it, bowed in the end to the censors, as a result of which the film was not funny and it flopped. Clothes, for those who could afford to choose them freely, had always been to some extent an expression of the wearer – of their status, character and taste – but it was in the popular Modernism of the interwar years, when so many men had died and women consequently found themselves with more room to manoeuvre in society, that the particular compound of woman + clothes, Woolf’s ‘frock consciousness’, became a significant aspect of female experience, a colour on the writer’s palette, a possible agent in a narrative.

It is at about this time that frocks – and other garments, but frocks especially – begin to enter fiction as more than accessories, when frock consciousness breaks the surface of public awareness and emerges in literature. But nothing happens all at once. Human character didn’t really change in 1910. Looking back there are two significant lines of descent. On the one hand is Jane Austen, who certainly cared about clothes and talked about them in her letters, but who is interestingly uninterested in them in her novels; more than that, she is positively hostile. Women who talk about clothes mark themselves out as stupid, vulgar or malicious. In Mansfield Park the culpably inert Lady Bertram is ‘a woman who spent her days in sitting nicely dressed on a sofa’. Mrs Elton in Emma condemns herself when she asks Jane Fairfax’s opinion as to whether she should put a particular trim on her white and silver poplin. After such a lapse we hardly need to be told that she is ‘self-important, presuming, familiar, ignorant and ill-bred’. In the very last paragraph of the novel she is allowed to linger in the wings to highlight the all-round moral superiority of Emma and Mr Knightley with her disappointment that their wedding was in such restrained good taste, ‘very inferior to her own’ with ‘very little white satin, very few lace veils; a most pitiful business’. The closest Austen comes to the question of frock consciousness is in Northanger Abbey, where she offers a rare direct comment on dress, but since the novel is a parody the remark is ironic, as defined by Christopher Ricks, in that it is both true and not true to the same extent at the same time. ‘Woman is fine for her satisfaction alone,’ Austen writes. ‘No man will admire her the more, no woman will like her the better for it.’ In parody the text works by being read in the reflected light of the other, known but unseen narrative. The satire bounces back and forth between the two in a comic hall of mirrors and that is where Austen leaves the woman who wants to be ‘fine’ but whose finery can get her nowhere, with nothing but her own reflection.

The conundrum of who women dress for, the unspoken question of why we mind about our clothes, as Austen herself did, when we know that the effect on other people is most often negligible at best and at worst deleterious, has never gone away. The correct answer today is that we dress for ourselves, but that isn’t quite true either. We dress to say something about ourselves and the question is: to whom are the remarks addressed? They can be, indeed often are, misinterpreted by men who think or pretend to think that it is for them or, worse, that ‘a woman who goes out looking like that is asking for it.’ The effect on other people is, however, one end of an arc, the point where it comes to earth in the outside world. The other end, the spring of the vault, is in the interior world of the wearer and it is somewhere between the two that frock consciousness happens. The other line of descent from the 19th century begins with Jane Eyre. Charlotte Brontë famously objected to Austen’s ‘Chinese fidelity’ to the external world of the real and material, and to ‘the smooth elegance’ of her narrative. However partial that view of Austen, she certainly understands dress entirely from the outside. Charlotte Brontë didn’t and in Jane Eyre frock consciousness springs fully formed into English literature as a bearer of narrative and emotional force.

On the night before her wedding, when Jane has her luggage ready for the honeymoon and the trunks are packed and corded, something stops her from attaching the labels written out for ‘Mrs Rochester’:

Mrs Rochester! She did not exist: she would not be born till tomorrow, some time after eight o’clock a.m.; and I would wait to be assured she had come into the world alive before I assigned to her all that property. It was enough that in yonder closet, opposite my dressing-table, garments said to be hers had already displaced my black stuff Lowood frock and straw bonnet: for not to me appertained that suit of wedding raiment; the pearl-coloured robe, the vapoury veil pendent from the usurped portmanteau. I shut the closet to conceal the strange, wraith-like apparel it contained; which, at this evening hour – nine o’clock – gave out certainly a most ghostly shimmer through the shadow of my apartment.

What hangs in the closet is a creature of limbo, unborn and undead, perhaps a chrysalis or a shroud: it exists outside narrative time. The white ghost is then followed by a black ghost, the dream by the nightmare, in the form of the actual Mrs Rochester, ‘tall and large, with thick and dark hair hanging long down her back’ whose own status is similarly indeterminate. ‘I know not what dress she had on: it was white and straight; but whether gown, sheet, or shroud, I cannot tell.’ Bertha Rochester fingers the wedding dress and then takes the veil and tears it, an action that has often been seen in Freudian terms as sexually symbolic, but that I think misses the point. The dress is not a metaphor, it’s a dress, doing what dresses can do, acting as a membrane through which ‘Mrs Rochester’ can pass. This at its most extreme is not so much frock consciousness as the conscious frock. It comes between one state of existence and another, as clothes themselves come between the naked self and the world, and it is also a channel of communication, semi-permeable, like the skin of an amphibian. Women have always had to be amphibious. No society has been designed for their comfort or convenience and as they move between the elements, the spheres of private and public, personal and professional, they must constantly adapt, assume disguise or camouflage. Not surprisingly, perhaps, the conscious frock in fiction is often seen in mid-air, being thrown from the roof of a New York hotel in Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar or drifting, sometimes on fire, through the fables of Angela Carter.

Meanwhile, back in the 1920s on the morning of her party, Clarissa Dalloway is mending a tear in her green dress. It is a favourite dress. It would be anyone’s favourite dress because it is both distinctive and yet suitable: it is one of the ‘little out of the way things’ that Mrs Dalloway’s dressmaker, Sally Parker, could create and yet at the same time not ‘queer’. The thing about Sally’s designs is that ‘you could wear them at Hatfield; at Buckingham Palace. She had worn them at Hatfield; at Buckingham Palace’; her clothes suit her character and at the same time they make her a suitable character on the stage of high society. And that is what many women want from their clothes, to stand out and to fit in to the same degree at the same time. As she sews and contemplates the dress a great sense of peace comes over her and the waves of silk become waves of the sea in summer until ‘the whole world seems to be saying “that is all” … fear no more, says the heart … committing its burden to some sea.’ Soothed by the dress and by the self it represents Clarissa Dalloway’s consciousness seems to pass into the ‘green folds’, so that when she hears a hand on the door ‘she made to hide her dress, like a virgin protecting chastity.’ Her reflexive action suggests the extent to which the frock has become her most private naked being. But the conscious frock is not always serious. There is great comic potential in clothes.

Woolf’s contemporary and acquaintance Edmée Elizabeth Dashwood wrote under the name of E.M. Delafield in the feminist magazine Time and Tide. From 1930 her column, ‘The Diary of a Provincial Lady’, was a popular feature, written in a persona set at a finely judged acute angle to her own life and character, about a woman living in the country married to a land agent who takes every opportunity to linger on the outskirts of literary London, struggling at times to keep her end up in the conversation. ‘Am asked what I think of [Rebecca West’s] Harriet Hume’, the Provincial Lady notes in November, ‘but am unable to say, as I have not read it. Have a depressed feeling that this is going to be another case of Orlando about which was perfectly able to talk most intelligently until I read it, and found myself unfortunately unable to understand any of it.’ Delafield portrays the permanently discomfited author at successive daunting social occasions for which she wears either My Black or My Blue, neither of which is ever quite right, while people who cross her path are often identified or misidentified by their clothes. At a dinner for the author of a novel called Symphony in Three Sexes of which she has never previously heard, the Provincial Lady decides that the woman in the blue tapestry dress must be the novelist and strikes up a conversation accordingly only to discover later that Blue Tapestry is in fact a sanitary inspector. The author is a man.

In both Woolf and Delafield there are reflections of the changes that were taking place in the interwar years for real provincial ladies from the lower middle classes upwards in their relationship with clothes: new fabrics, new colours, new garments that made dressing and undressing yourself even easier. In 1917 Gideon Saundback patented the ‘separable fastener’, which became known after 1923 as the ‘zipper’ and in Britain as the ‘zip’. It soon migrated from the military to footwear (no more button hooks) and then in the 1930s to clothes. Also liberating in its way, was the ‘department store’. Department stores had existed since the 19th century but it was in the 20th that they blossomed. Selfridges opened in 1909 and by the 1920s it looked like a cross between the British Museum and Mae West’s bathroom. Between the wars these grands magasins became a striking architectural presence in London, Stuttgart, Budapest and Paris. The department store could fairly be described as the art deco building type. La Samaritaine got its famous extension, as did Le Bon Marché. In Germany, Modernism overtook the Moderne at Eric Mendelsohn’s stores for the Schocken company.

Admittedly Marshall and Snelgrove in Oxford Street was never quite in the same league. By 11 October 1928, it had been taken over by Debenhams. That was the day Orlando, in her last manifestation, visited. Delafield enjoyed teasing Woolf about Orlando, but she had no real trouble understanding it. Nor would her Provincial Lady be at a loss to know why, after travelling through so many centuries, Orlando should arrive in a department store. As she enters from the hurly burly of the street the essence of department store joy comes over her: ‘Shade and scent enveloped her. The present fell from her like drops of scalding water.’ And, ‘each time the lift stopped and flung its doors open,’ as she rises up the floors, ‘there was another slice of the world displayed with all the smells of that world clinging to it.’ The department store is in decline these days, but it is still possible in Harvey Nichols or perhaps Fenwicks to have that sense of luxuriating in peace and freedom – if you like such shops. I like them for the reasons that some women and many men dislike them. There are rarely any windows to the outside. You navigate by departments and designers. The busy world is hushed, all is tissue paper and the promise of lives embodied in perfect clothes which, however unsuitable or unaffordable in reality, seem briefly possible in the flattering electric light.

The department store was a corner of the world that was, unusually, laid out for the convenience of women, and for their comfort. The business of Marshall and Snelgrove was to create an environment in which women without male companions could linger, and there were not many such places in the 1920s and 1930s. Clubs were mostly for men and those for women tended to be austere. A woman or women unaccompanied by a man would not be served at a respectable bar. In the department store there was a restaurant or a café. There was also, very importantly, a women’s lavatory. You could spend all day in the shop, meet a friend, buy what you wanted or buy nothing. And provincial ladies didn’t have to come to London. Marshall and Snelgrove had branches in the resorts and industrial cities of the North, in Scarborough and Leeds. Liverpool, Britain’s greatest seaport, had its very own Bon Marché, named after Boucicaut’s Paris store although it was founded by a Londoner called David Lewis. Between 1920 and 1924 it was given an art deco makeover and was regarded as ‘one of the finest examples of modern architecture that Liverpool possesses’. There were also Owen Owen and Lewis’s, which catered for customers from the middle and working classes, while in Bold Street, the ‘Bond Street of the North’, there were more exclusive establishments.

About one patron of the Liverpool women’s clothes shops, a woman who was neither famous nor fictional, we know a great deal and we know it almost entirely through her clothes. Emily Tinne was born Emily Margaret McCulloch in India in 1886. Her family were minor figures in the Raj, her father a Presbyterian minister at Chinsurah in West Bengal. Emily was sent to boarding school in England, after which she trained as a domestic science teacher and took her first job, teaching at the Liverpool Training School of Cookery and Technical College of Domestic Science. In 1910, at Toxteth, she married Philip Tinne, a local GP born in British Guiana and educated at Eton and Magdalen College, Oxford. The Tinnes were a trading family who had made and lost money from time to time in shipping and sugar, and Emily and Philip belonged to the solid Liverpudlian bourgeoisie. But the Tinnes would not have considered themselves in any pejorative sense provincial. The doors of Liverpool’s St George’s Hall bear the letters SPQL: for its peers Liverpool looked not to London but to Rome. In that interesting year, 1925, which saw the publication of Mrs Dalloway and the birth of art deco, Dr Tinne inherited a share of the family fortune, after which the Tinnes lived in a somewhat higher style.

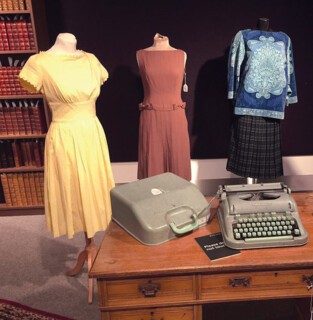

When Emily Tinne died in 1966 her daughter, who had lived with her, began to clear the house. It took her forty years to go through all her mother’s clothes. Between 1966 and 2003 she donated more than seven hundred items to the National Museums, Liverpool as well as a collection of fashion magazines. This is now the Tinne Collection and it was the subject of an exhibition, curated by Pauline Rushton in 2006, Mrs Tinne’s Wardrobe. On the very morning of Clarissa Dalloway’s party, if Mrs Tinne was shopping (and it is a fair bet that she was), she would have been in Bold Street while Mrs Dalloway was in Bond Street. It was certainly about then that she bought an art deco afternoon dress in wool crepe. Had she gone to the party in the evening we might imagine her in silk crepe and rayon jersey, one of those new wonder easy-care fabrics, and with its pattern of clear glass and silver beads the dernier cri in art deco.

From the museum’s point of view the Tinne Collection is a wonderful historical resource, which includes some rare early examples of brassieres, and, as Rushton puts it, it allows one to see ‘a broad range of clothes worn by one person every day and over a long period of time’. But I am not sure that is exactly right. The range is certainly there: starting in 1910 with the swimsuit Emily bought for her honeymoon, it continues up until 1939, when the outbreak of war put a stop to Mrs Tinne’s shopping. It is a biography in clothes and a period study. Types of garment that no longer exist mark punctuation points in a life that no longer exists: the bridge coat, the motoring bonnet with built-in hairnet, the dinner dress and matching coatee. But many of these clothes have either hardly or never been worn. Some still have the price tags on them. Rushton wonders whether Emily Tinne had a philanthropic desire to support the shop girls who worked to commission. Or was she just a compulsive shopper of the sort who are so fascinating to viewers of Channel Five? Possibly. There were certainly times when she resorted to the familiar practice of buying a size too small in the hope of losing weight. But when she didn’t there was no apparent despair. Among the fashion magazines to which she subscribed were the bluntly titled Smart Fashions for Outsizes and Smart Fashions for Wider Hips.

While cataloguing the collection Rushton talked to Mrs Tinne’s daughter, from whom she received some interestingly contradictory information. ‘The survival of numerous dinner gowns or similar evening dresses,’ Rushton writes, ‘indicates that the Tinnes must have dressed for dinner, at least some of the time, although Alexine Tinne does not recall this having been the case.’ Further on she writes: ‘Some of the later garments are too grand for dinner at home and must surely have been worn on some other, more formal, occasion, such as at a party or official function,’ yet, she adds, ‘Alexine does not recall her parents socialising regularly.’ On the contrary, Dr Tinne made a point of holding an evening surgery and the only occasions Rushton can be reasonably sure that the Tinnes attended were receptions at the Liverpool Medical Institute.

However smart the institute it would not seem to justify quite such an outlay on evening wear. And as Rushton and Alexine continue their conversation in the exhibition catalogue, a slightly odder picture emerges. In contrast to the great array of hats there are hardly any shoes. Those that do form part of the collection are mostly stout and sensible and have been worn. Neither are there many handbags. Alexine explains that her mother wasn’t so interested in shoes and bags, but she couldn’t have gone out in those clothes without shoes and surely wouldn’t have gone without suitable accessories. The figure that emerges from Mrs Tinne’s wardrobe is eerily like the mannequins on which the museum shows the clothes, footless, their limp arms empty-handed and, hovering above where the head might be, a wonderful hat. No feet, no face, no baggage. I don’t know but I suspect that what we are watching is the manifestation, like ectoplasm, of an actual frock consciousness, of a life lived out in clothes, some worn, many not, of evenings while her husband held his surgery, spent in the imagination at soirées like Mrs Dalloway’s in a state of mind like Clarissa’s as she mends her dress, half in and half out of the material world. I can’t be sure if that was what Emily Tinne did but I believe this is the closest thing we shall find to a case study of the state of mind Woolf describes in her diary as she tries to put her finger on what she feels about clothes: ‘Happiness is to have a little string onto which things will attach themselves. For example, going to my dressmaker in Judd Street, or rather thinking of a dress I could get her to make, & imagining it made – that is the string, which as if dipped loosely into a wave of treasure brings up pearls sticking to it.’

While Emily Tinne was shopping in Liverpool, up in Edinburgh, Cissie Camberg, her almost exact contemporary, was buying hats. In the 1920s in the respectable but chilly and soot-stained city, the hat of choice or at least of convention was the pot-shaped cloche. But Mrs Camberg favoured another kind of hat, as her daughter Muriel Spark recalled: these were ‘quite different’, ‘large, wavy-brimmed, shady and bedecked’ – more like Emily Tinne’s. These hats were ‘utterly impractical’, Spark wrote, ‘outside of Ascot races, and possibly the summer opening of London’s Royal Academy: four hundred miles and many many more hundreds of cultural distances from our puritanical Scottish capital. But my mother could not resist them.’ When questioned by her daughter about her expensive hat habit (‘she could never pass a hat-shop, particularly if the milliner gave her cash-credit’), Mrs Camberg would reply that her hats would be ‘lovely for a garden party’. Muriel Spark, like Alexine Tinne, does not recall any such occasions in her mother’s life until, when Muriel was living in Southern Rhodesia, she got a letter from her mother announcing that she had, at last, been invited to an Edinburgh garden party in aid of a Jewish benefit fund. Letters took two weeks to reach Scotland so Muriel wrote back at once to warn Cissie, but too late. Her mother had appeared at the garden party in one of her glorious hats to find herself a gazelle among dung beetles under a leaden Scottish sky. ‘It was very dreary,’ she reported to her daughter. ‘They were all wearing tweeds.’

Spark, who was remembering her mother in 2002 in an essay called ‘The Celestial Garden Party’, concluded that some clothes should be bought ‘because they are so attractive, so irresistible in the shop’ but they should never be worn or used. Perhaps. When the arc from interior life to the outside world is too wide to take the load that is perhaps good advice. The shock as the private self collides with the public one, when the carefully arranged reflection in the glass at home becomes the overlit snapshot on Facebook, can be shattering. Spark was herself a mistress of frock consciousness. In The Girls of Slender Means, which is set shortly after the end of the Second World War in a hostel for young women, the spirit of the place is an evening dress – designed, naturally, by Schiaparelli. It is made of taffeta and is dark blue, green, orange and white in a floral pattern. The dress, strictly speaking, belongs to Anne Baberton and was given to her by ‘a fabulously rich aunt’ but, perhaps more than any dress since Jane Eyre’s, it exists as an independent consciousness in the narrative. Anne lends it to those of the other girls who can fit into it when they have an important invitation, but the dress has a social life of its own. ‘You can’t wear it to the Milroy. It’s been twice to the Milroy … it’s been to Quaglino’s, Selina wore it to Quags, it’s getting known all over London.’

The dress is the girls’ collective unconscious. As such it fascinates Nicholas Farringdon, one of the young men who goes out with several of the girls. By the time the story opens we know that Nicholas suddenly gave up his civil service job and took holy orders, later to be murdered in Haiti. By the time it ends we know how he came to his vocation. An unexploded bomb in the garden of the May of Teck hostel sets fire to it, trapping the girls on the top floor, where the only way out is the narrow lavatory window. Having been in the habit of using the window to get onto the roof to sunbathe or have sex they know that in order to get through it they must have hips that measure less than 36 and a half inches. Slender girls of slender means. The beautiful Selina has no difficulty in getting out but, as the building collapses, she is seen to go back in and to emerge again through the smoke carrying ‘something fairly long and limp’ that Farringdon thinks at first is a body but the head and shoulders are a coat hanger. Selina passes him with the Schiaparelli dress and vanishes. In his notes, found after his death, Farringdon had written that ‘a vision of evil may be as effective to conversion as a vision of good.’ The ending is ambiguous, rather as Woolf’s choice of dress for her Vogue sitting was ambiguous. Selina is perhaps the angel of death, and something certainly dies at the end of the book: a moment in history, or an association of women who have long since gone their separate ways but were for a moment one spirit.

Spark published The Girls of Slender Means in 1963, the same year Sylvia Plath published The Bell Jar, a largely autobiographical novel permeated with frock consciousness. The protagonist, Esther Greenwood, has come to New York to a dream job on Mademoiselle magazine, but she has a breakdown, the dream becomes nightmarish and she throws her clothes away: ‘A strapless elasticised slip which, in the course of wear, had lost its elasticity, slumped into my hand. I waved it, like a flag of truce … piece by piece, I fed my wardrobe to the night wind … like a loved one’s ashes.’ It is a description that shares the smoke and ashes of the dead dress in Spark. In real life Plath continued to wear the shirt-waister dresses, hats and gloves favoured by Mademoiselle and its readers. Ruth Fainlight remarked that Plath reminded her of ‘one of my New York aunts dressed for a cocktail party’ and suggested that this indicated that she was always trying to fit into a role she could not play. That perhaps is too simple, for there was something in the clothes that was truly herself: she was not only the cremator but also the loved one whose ashes were cast away in the wind. The extent to which Plath’s self is understood to be embodied in her clothes is suggested by the prices some of them fetched when they were included in a sale of Fine Books and Manuscripts at Bonham’s last month. Lot 315, ‘a pleated green tartan skirt’ with her nametape ‘in blue lettering’, went for £2125.

Plath and Spark perhaps mark the end of what can reasonably be described as post-war writing. The peculiarly florid phase of interwar frock consciousness in life and literature ends with them. That strand of female experience on which Woolf was trying to put her finger remains elusive, though time and distance throw it into some relief. Today frock consciousness takes other forms but it continues to operate and to obey its own, sometimes mysterious rules – rules which dictate, among other things, that tights should stop at Derby.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.