It seems to be a foregone conclusion that Vanessa Bell isn’t much good. There are those devoted types, of course, for whom the sensibility of her paintings, as well as their subjects, makes them windows into a beloved world. But perhaps they are seeing something more than this. If so, it shouldn’t be surprising; they have been looking the longest. The current retrospective of her work (until 4 June) is the most comprehensive yet, but it’s an awkward proposition: to introduce an artist to half the audience and rescue her from much of the rest. Dulwich Picture Gallery has often proved courageous in such undertakings, but here there is the added difficulty of Bloomsbury’s long shadow. The curators can’t help but enact the impossibility of separating the work from the life. Some of the ways in which they fail are better than others.

There are things that are helpful or interesting to know, in any case, like that Bell studied under Sargent at the RA, and took private classes as a teenager. As children she and Virginia agreed on their different spheres, a division of talents that wasn’t without envy. She was embarrassed later by her early taste, which ran also to Sickert and Whistler and Fred Walker and G.F. Watts, and later still grew unembarrassed by it again. She was 21 in 1900, and though there must have been quite a lot to show for it, her youthful work is little known (some of it was destroyed during the Blitz) and not in evidence here. The earliest exhibit at Dulwich is a small painting from 1908, Saxon Sydney-Turner at the Piano. It has something of Sargent’s slickness, though not put to quite the same effect (she liked filling in where he liked trailing off) and shows Sydney-Turner in profile at his instrument: the flair of his moving hands counters the overall studiousness. An inspired detail – a blob of pink under the ear – lifts the whole image. It is the work of a young but not immature artist: Bell had studied and exhibited, and following the death of her father in 1904 had lived in much greater freedom with her siblings in Gordon Square. She married Clive Bell in 1907; when she painted Sydney-Turner her first son, Julian, was a few months old.

Almost all the most important things in her life were yet to happen though, and they happen in the other paintings that make up the first room at Dulwich: portraits from the years immediately after the first post-impressionist exhibition of 1910 (she exhibited in the second). Bell was close to Roger Fry, who organised the show, but it was seeing the pictures – not just discussing theory – that brought about a new spontaneity in her work. There is a great sense of exhalation; instead of carefully loading a brush, like Sargent, and making just the right mark in layers of thick oil paint, she would sketch rough outlines and then fill in the shapes haphazardly. She suddenly saw the possibilities afforded by imaginative use of bright colour. Shadows could be green or blue; highlights orange or yellow or pink. In a painting of Duncan Grant in front of mirror, from 1915, the blue and turquoise of the scarf on his head trickle down to illuminate his hair and the back of the chair. The brushstrokes, especially in the top half of the painting, smirch and smudge, covering the surface sporadically – it seems, instinctively. In a portrait of Iris Tree from the same year, anatomy and underdrawing are disregarded (one doesn’t notice, at first, that her legs have all but disappeared) in order to say something more suggestive through the pattern of yellow and pale green, which extends to the fabric of the sofa. Although the paintwork is a little scrappy, one senses Bell working out the tonal harmonies: the yellow abstract shape in the top right (a doorway?) echoes the yellow square of sofa on the opposite diagonal. Painting across the canvas all at once, rather than in layers, works to her advantage here: the difficulty of filling in the red background around the figure creates a sort of halo (it’s hard to get the brush right up to the edge), which emphasises Tree’s Madonna-like monumentality; the sedateness of her expression and clasped hands.

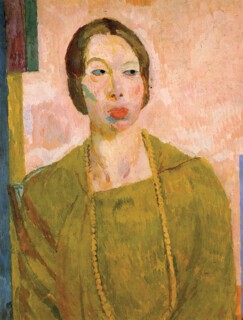

More remarkable, if not so successful in totality, are Bell’s paintings of Lytton Strachey and David Garnett, from 1913 and 1915. The former’s glasses and beard are painted bright yellow in a strange experiment; the latter, a topless portrait, has a mother-of-pearl luminescence to its skin tones, the small dark dots of Garnett’s eyes and set mouth revealing a wariness beneath the fleshy complacency. These are paintings that seem undetermined, still full of lively possibility. Heavier, but more complete, is Bell’s portrait of Mary Hutchinson (1915), a purse-lipped vision in green, with a suspicious sidelong expression. The tones are a little nauseating – the peach-pink daubs of the background, the murky yellow in her dress – but the boldness of the colouring on the face and the abstract shapes that frame her (cues to ‘modernity’) are striking. The overall effect of having these works together in a room is one of huge vitality, and of flickering, permeable surfaces, which don’t quite reproduce in print. There is an oddly affecting directness and sensuality about them; moments taken in at a glance and then worked through methodically.

This period of experimentation coincided with Bell’s involvement in Fry’s Omega Workshops, of which she and Grant were directors. Perhaps this is why the Dulwich show jumps abruptly in the second room to her design work, including the familiar (maybe too familiar) covers for the Hogarth Press, her Omega fabrics and screens, and the paintings she made for bedheads and overmantels, which are sketchy and too few to tell us much, though they provide some gossip: Nude with Poppies was designed for Mary Hutchinson’s bed when she was Clive’s lover. It seems a diversion to try to include this side of Bell’s work; the point of doing so, I think, is to make a case for her abstracts of 1914 and 1915, which are among the earliest examples of non-representational work in Britain. The formal motifs in some of the portraits take centre stage here, and Abstract Painting (1914) is particularly nice with its yellow background and pink and blue quadrilaterals. A lot of critical weight seems to rest on whether these paintings resulted from a radical simplification of forms, deriving from works such as Bedroom, Gordon Square (1912), where the wardrobe, windows and rug are already flat rectangles of colour, or whether they were simply an outgrowth of her work for Omega, like the rug designs, which makes her less of a pioneer. The answer is surely close to the latter (compare them with Bomberg’s In the Hold of 1913), but the distinction isn’t entirely straightforward. One can see the effect that working on squared paper, say, had on her fabric designs, inspiring the lovely jagged edges of ‘Maud’, and where that sort of two-dimensional thinking might lead, but both painting and design (and their inbetween state, collage) were problems of space: how to fill it and what sort of tensions and harmonies could be created within it. Bell didn’t go further with pure abstraction; there were values in life, she claimed, ‘movement, mass, weight’, that had inherent aesthetic value, which ‘flat patterns’ couldn’t reproduce.

Perhaps this is why she clung firmly to the painterliness of her paintings. Their compositions may sometimes be influenced by her design work, but their surfaces rarely are. Patches of colour are almost never flat or evened out in her paintings, brushstrokes are visible, sometimes pencil too, and planes are liable to fade and blend in and out of each other. The useful comparison may be with Matisse, whose work she knew well (not least from the second post-impressionist exhibition). Matisse didn’t disguise his brushstrokes either, and like Bell’s many of his paintings have an illustrative, colouring-in quality, but he was less likely to dilute his paints, so that each area stands out strongly, and he used them more graphically, giving each part of a picture its own character. Bell’s brushstrokes are smaller, the effect more uniform, creating a surface texture that ripples across a canvas. She would thin her pigments too, so that even within an area of single colour, like the background of Still Life with Wild Flowers, there are lots of different tones and a good deal of patchy variation and striation.

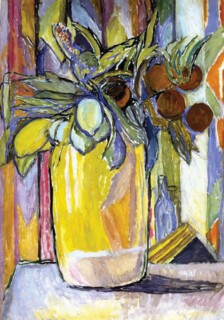

Formal ideas about shapes and colours do underpin her paintings, however, and it would have been more interesting to try to bring out this relationship to her designs, at least for the paintings from the Omega period. Oranges and Lemons (1914), for instance, features a strip of the Maud fabric in the far right of the background, and the design reverberates through the picture. In the centre, though slightly to one side, a large vase stands on a table, full of leafy branches of fruit, which were sent from Tunis by Grant. ‘They are so lovely,’ she wrote to him, ‘that against all modern theories I stuck them into my yellow Italian pot and at once began to paint them. I mean one isn’t supposed nowadays to paint what one thinks beautiful.’ Behind the flora a pattern of vertical lines and V-shaped prints suggests curtains, or hanging fabrics, but it’s not entirely clear; object and motif are almost indistinguishable (the bottles in the middleground could belong to either) and colours weave in and out of their subjects. The brilliant blues and lilac that outline the fruit and leaves, the pale green of the leaves themselves and the dark orange fruit, are all echoes of the Maud pattern. Although as a canvas it’s as close and crowded as any of her pictures (despite her love of Piero della Francesca, Bell seems to have had a horror of bare or architectural space), the exuberance of the colours and the expressive paintwork distinguish the separate parts of the picture much more daringly than they do elsewhere. If there’s something clotted about her surfaces at times, here it doesn’t preclude movement and space; in fact she has to use the shadow cast by the vase to anchor it.

Despite the obvious influence of Matisse on her work, the artist Bell often seems closest to in spirit is Bonnard. There is an affinity in their domestic playfulness, in the shimmer of marks and diffusive pinks and yellows. At times she seems as interested as he was in the way patterns of colour can work across a scene, destabilising it through decoration. She does this in two paintings at Dulwich: View of the Pond at Charleston (1919), which Julian Bell writes about in the catalogue, and Landscape with a Pond and Water Lilies (1915). It’s not a coincidence that both feature water. Landscape with a Pond is the bolder of the two; as you begin to piece the image together from all the disparate areas of colour (pale greens, and lilac, and blue, and oh! pink) you suddenly realise that the space between the two flatter groups of green – the lily pads – is a reflection. The painting jumps into focus, and you can then follow the outline of the pond all the way round; the edges become clear but the water now bulges like a great teardrop, threatening to overflow. View of the Pond is more composed but there is a similar instability, and not just from the angled windowsill that frames the view (we are inside looking out). The pond is the brightest part of the picture; its layers of reflection (tree over cloud over sky) surround and submerge the dark vase which projects into its space. Is the purplish highlight still part of the vase or of the water? Although it’s painted in oils, View of the Pond suggests her watercolours are worth further exploration (there’s only one in the exhibition, The Coffee Tray).

At points like this, Bell becomes quite an unfamiliar artist; more curious, inspired, comic even, than she’s given credit for. There’s a sense, nonetheless, in the exhibition of having to account for her ‘rustic touch’ or ‘homeliness of palette’, and apologise for the conventionality of her subject-matter. There are many criticisms that this show leaves obscure or unaddressed (perhaps rightly): that she was overpraised by her contemporaries (she has certainly been undervalued since then), that her paintings are domestic or amateurish, that the Bloomsbury Group fiddled during the war, that the Omega creations were shoddy, that her best work is derivative and her late work poor. Much of this seems to matter less than it did – who cares if the handles fell off their jugs? – or doesn’t seem particularly helpful: when is an artist derivative and when are they ‘in dialogue’ with another painter?

But in many ways, romantic ideas about the Bloomsbury Group have been most damaging to Bell, who was the least vocal of them (that in itself has become part of the myth; Virginia called her ‘mute as mackerel’, and worse). The image of the group, which her designs certainly contributed to, is bound up with their class, and their failure to start a movement. It isn’t difficult though to see her as a radical: a woman who scorned convention, who created a world in which she could retreat and paint, who had a firm sense of what art should be – and what it shouldn’t (she would dismiss other people’s work with the phrase ‘pretty and quite empty’ and derided sentiment and ‘English sweetness’). In trying to see her as a bridge between Victorian Kensington and Picasso’s Paris, as critics often do, she is stretched too thin; it helps, I think, to bear in mind that her shortcomings often signal impatience, or a rejection of certain values. There is a moment in her letters where she visits the memorial exhibition for G.F. Watts (he had been a family friend) and finds that his work now appears childlike to her. What she admired was not traditional skill or charm, or storytelling, but authenticity, directness. It’s a small thing, a biographical thing, her disdain, but it points to the approach she lived by: ‘I believe all painting is worthwhile so long as one honestly expresses one’s own ideas. One needn’t be a great genius – all the second-rate people are worth having so long as they’re genuine, because of course one always must have something of one’s own to say that no one else has been able to say – and that’s always interesting.’

More than anything Bell is in need of coherence. Artists don’t just exist: they are given shape by galleries and critics and historians. It would help, to begin with, to see a great deal more of her work: there is no catalogue raisonné and the Dulwich show, due to its size, is selective (too many worthwhile paintings are missing). Her inconsistency of style has made her hard to see clearly, and critics have often been drawn to works which are not representative (like the early and austere Iceland Poppies). It seems a shame that the exhibition ends by singling out Studland Beach (1913) as her masterpiece, as so many others have done. It’s a striking painting, possibly the simplest in execution, showing two groups on each side of a diagonal stretch of beach; in the distant group a woman stands framed by a white canvas tent, beyond her is the sea. Part of the appeal of Studland Beach is its enigmatic drama; it could be a scene from an Ibsen play. Bell revised the original version (also in the exhibition) considerably, simplifying the forms and making the main figure more shapeless and aloof. Naturally there has been speculation about the dramas in her own life it might represent. But it has been set apart from her other work to an unnatural degree; comparison with the earlier version, and with likely inspirations (such as Wilson Steer’s The Beach at Walberswick) ought to bring it back within her oeuvre, rather than letting it stand out as a modernist aberration.

It might be more rewarding to be interested in Bell as she is, rather than as we would like her to be. I was struck walking through the exhibition by her sensitivity to women sitters, and to groups in conversation or at work. Her paintings of Virginia in the orange armchair, especially the one of her crocheting, are compelling, and many of her portraits reveal an idiosyncratic attention to pose and heft – the shoulders of her sitters are often intriguing. She has been criticised for not always filling in faces, as though this were a great failure (Matisse didn’t either) but there are other ways of reading facelessness; her photographs, which show figures blurred by movement, could be one.

Of the exhibition’s omissions, the saddest to my mind is Lady with a Book, from 1946, not least because it upsets notions about her artistic decline. In some respects, it’s a conventional painting: the subject, in black coat and yellow gloves, sits in quiet reverie while the background (a painted wall, or, quite possibly, her imagination) takes on Bell’s most exuberant pattern of colourful leaves and swirls. The woman’s composure is held firm by her pose, and by the central column of white which runs from her cheek to her lace to the papers (or book) on her lap, but her thoughts are elsewhere, and the curve of light on her face echoes the curving, spiralling shapes unfolding in the background. The jar of flowers, half out of view on the left, maintains the illusion of a ‘real’ pictorial space, but something transformative is going on here. The rendering of costume and hat is restrained; the fussiness of the flowers provocative; the combination of repose and wonderment distinctively Bell’s.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.