A century ago Roger Fry tried to sum up Rodin’s approach to the human figure. What mattered most to Rodin, Fry decided, was the ‘unit’, not unity: ‘His conception of a figure is always so exceptional, so extreme, that every part of the figure is instinct with the central idea, every detail of hand or foot is an epitome of the whole, and the final composition of these parts is often a matter of doubt.’ The exhibition Rodin and Dance (at the Courtauld until 22 January) makes it clear that as Rodin drew and modelled the body, the final composition was usually the last thing on his mind – in this Fry was right. As for the unit, the unique particular of the body in action, it could only be arrived at with difficulty, via movement, energy, extension, pattern, process, outline and shape.

This sharply focused show brings Rodin’s complex process alive, partly by deploying photographs of the dancers he knew well: Loïe Fuller, Ruth St Denis and Isadora Duncan. It would be hard to assemble a more fascinating set of early 20th-century performers, or a more talismanic group of images. The photographs at the Courtauld were chosen from hundreds owned by Rodin; they all captured dancers he admired and who admired him in return. Fuller is shown framed by whirling drapery; St Denis appears lean and erect in The Yogi, one of her ‘Eastern’ dances; the perennially white-clad Duncan is caught mid-flight at the fête champêtre Rodin’s friends staged for him in 1903 after his promotion to Commandeur de la Légion d’Honneur.

Rodin sketched these dancers (all American women of the liberated sort) on more than one occasion. Most often he used a medium-hard pencil and relied on a fast-moving line or tangle of lines, over which watercolour was sometimes floated like a veil. Sometimes he let his pigments puddle and bleed, with results that somehow manage to align the techniques he used in drawing and the energies his subjects expended in dance. This alignment of drawing and dancing, the Courtauld exhibition suggests, is among Rodin’s greatest discoveries. It led him to a new conception – a new practice – of sculpture. Duncan spoke of her determination to ‘dance a different dance’. Rodin didn’t articulate things in that sort of way, but the artistic terms he found for the dancing body made his version of difference – it encompassed both conception and execution – a rule.

By the end of the 19th century, dance in Paris was no longer limited to those staples of café-concert and Opéra, the can-can and the ballet so beloved of Degas. Dancers and dance troupes were arriving in the city from all over the globe. Some made their way to Rodin, or he made his way to them. He was in the audience in 1906 at the Paris performance of the Royal Cambodian Dance Troupe. It so sparked his interest that he followed the troupe south to Marseille where these ‘petites princesses jaunes’, as Le Figaro called them, were to perform at the Exposition Coloniale. These highly schooled young dancers were capable of movements of the body Rodin had never seen before. As he told L’Illustration’s reporter, the Cambodians’ arms and fingers made unprecedented angles and patterns; their limbs gave rise to undulations that somehow travelled laterally across the limbs and torso in opposing curves. And through all of this, the dancers’ legs stayed bent, creating a ‘receptacle of leaps’, a reservoir of energy that ‘allows them to lift themselves, to grow’.

Much of this – leaps, curves and more – registers vividly in the sequence of drawings at the Courtauld. The sheets show the dancers facing us and in profile, whole or in part. Knees lift and bend, arms and hands too. When captured on paper such disjunctive movements form patterns with a life of their own. The artist’s line snakes in and around the moving body, extends to the limbs, then unravels in a flurry of fingers and feet.

One of the exhibition’s achievements is to show us how Rodin managed to capture such movements; how, practically speaking, his representations of dance came into being. We soon learn, for example, just how hard he had to work to understand the way the Cambodian dancers really moved. Not only did it take him dozens and dozens of drawings – more than 150 are known – but he also sought instruction from two uncannily elegant objects he acquired, plaster casts of an unknown Javanese dancer’s right and left arms. Elegant, but inanimate. No wonder he sought out stasis. The hands of the young dancers were adapted to a precise and disciplined school of movement over long years of training. Wrist, palm, thumb and fingers – each had to learn to play off and against the others, while pursuing its own separate path.

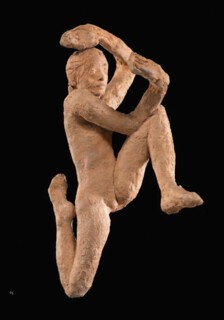

Rodin and Dance would have more than satisfied as an exhibition if it had done nothing else but present this evidence of Rodin’s engagement with dance around 1900; in other words, if we had simply been shown the place of the sculptor’s work within the overlapping worlds of art, entertainment, colonialism and female emancipation. But this is only the beginning. Having so succinctly located its subject, Rodin and Dance carries out a leap of its own. The second part of the installation presents the results of months, even years, of investigation by curators and conservators into a set of sculptures in terracotta and plaster that since his death in 1917 have been part of the vast collections of the Musée Rodin. There are nearly twenty dancing figures on view, most about 30 cm high, and all but one displayed in a single vitrine that travels the length of the gallery. Seen together the procession of dancers forms an open set of ‘movements’, each one distinct in terms of posture and kinetic energy, but, one gradually comes to realise, assembled from the same small set of parts: this torso, this leg, this arm, a different leg, a different hand. The only constant is the head. They form a long parade of naked figures, stretching and leaping, kicking and reaching, all classified under a rubric, Mouvements de danse. Not ‘dancers’, interestingly, but ‘dance movements’. You can almost hear Yeats asking: ‘How can we know the dancer from the dance?’

Why does the same general idea of dance subsume this varied set of bodies? The explanation lies in the way each figure was made. All of them were assembled from a collection of possible parts. And those parts – legs, arms, torsos, heads – were multiples: each was pressed or cast in a mould, to be put together by an assistant as the master saw fit. There are nine moulds in all, brought from underground storage at Meudon, Rodin’s retreat in the Paris suburbs, for the exhibition. The moulds lend weight to the Courtauld’s central argument. Above all they confirm that though Rodin’s dancers resemble real bodies, he arrived at resemblance in a new way. Most unexpected is that all of these bits and pieces have their origins in just two figures, which the show’s curators characterise as two basic formats or types. Each of these plaster models was pragmatically cut into parts. Both were reduced to abattis, the butchered bits and pieces that, though still bearing the scars of their making, were used as the basis for the moulds.

Is this starting to sound too technical? Sculpture is technical, as well as technological, and this determines the way we understand its possibilities, and what its variations seem to mean. It is hard to imagine a visitor to the Courtauld failing to notice that Rodin’s way of working made the most of sculpture’s traditional reliance on replication and reproduction. For Rodin, replication was not simply the process that allowed creation, it became creation, and with this transformation he left tradition behind.

One consequence of this way of working is that the figural composites he put together have more to say about bodies than their artificiality leads one to expect. Look at the terracotta known as Mouvement I+. One of Rodin’s most striking compositions, it shows a figure leaping. Now imagine Rodin joining arm and thigh and torso, adding a hand, smoothing a seam (or not). Despite the obvious artifice of such bricolage, it is hard not to be reminded that our own bodies too are a set of parts more or less symmetrically matched up. Our surfaces bear scars, display breakage, and as in Mouvement I+, our gestures sometimes convey the guarded wariness of flight. I think again of Fry’s claim that each part of Rodin’s figures is ‘instinct with the central idea’.

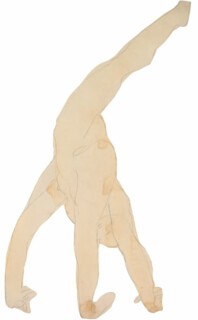

Against this background, there is special satisfaction in discovering that Rodin spent years trying to track down a model and acrobat known as Alda Moreno to ask her to pose. The attraction lay in her rock-solid balance and her astonishingly supple spine. This she displayed in a 1903 photograph produced as part of a series called Le Nu académique. Rodin’s copy is on view in the show. In it Moreno stands with her left leg solidly planted, while her right leg reaches up and behind so that, with her spine fully arched and extended, her right hand can stretch back to grasp her right toe. A glance at the photograph is enough to make clear that the pose Moreno achieved is as artificial as flesh and bone can be. Rodin drew and modelled it again and again. These images are among the subtlest, the most softly shaded, in the show.

After a while, he no longer needed Moreno’s collaboration. In pursuit of the essence, the energy, her pose mobilised, he began to work from the drawings he had made of her, tracing and retracing them, flattening and simplifying the viewer’s sense of a three-dimensional presence into a two-dimensional pattern, a template. In the end what remains of Moreno’s muscularity is lightness, an elusive line of movement, that has left her body behind. It’s a transformation Rodin’s dancers seem to dream of: again and again their embodiment pursues its opposite, as if disembodiment was what Rodin aimed for as he worked. Thus we finally find him cutting the paper background away from the bodily patterns distilled from his dancers. What remains is an essence, a condensation. In Rodin’s cut-outs, unit and unity are one and the same.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.