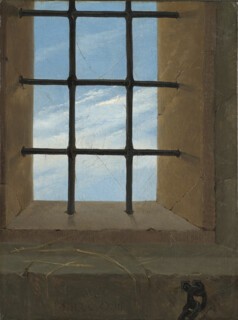

AView of the Sky from a Prison Window, painted in 1823 by the German artist Carl Gustav Carus, now hangs in the National Gallery. It is one of a handful of recent acquisitions, which include an intricately painted Banquet Still Life by the 17th-century Dutch painter Floris van Dijck, and the spectacularly eccentric (and currently anonymous) 16th-century Virgin and Child with Saints Louis and Margaret, with its grotesque dragon at the bottom of the frame. A View of the Sky from a Prison Window, both in its modest dimensions – no larger than a sheet of A4 paper – and plain subject matter, might seem rather underwhelming by comparison.

The subject is a barred stone window looking onto a patch of blue sky and wispy clouds. Fine strands of cobweb criss-cross the window bars, and a few stalks of straw lie on the cracked window ledge. Carus’s signature appears next to the top three links of an iron chain set in the wall. There is something Magrittean about the emptiness and puzzlement of the small scene. There may be a clue to its meaning in the strange perspective of the window bars, their connecting joints angled outwards to suggest a point of view closer to the window than the point from which it has been painted, as though the viewer were a single eyeball, drifting slowly towards freedom.

Carl Gustav Carus was born in Leipzig in 1789 and was studying medicine at the university when Napoleon’s army marched into the city seventeen years later. His specialism was anatomy and his work on the morphology of bones led to the discovery of a homologous form common to all vertebrates – an idea that was important to Darwin. He also studied painting at the Leipzig Art Academy and showed his work at the Kunstakademie in Dresden (where he became friends with Caspar David Friedrich), though his paintings are strangely devoid of the scientific observation that underpinned his anatomical studies.

On completing two doctorates, in philosophy and medicine, and in the middle of the Napoleonic Wars, he took a position as an obstetrician at a maternity hospital in Dresden (his Lehrbuch der Gynäkologie of 1820 was the first systematic work on the ‘science of women’). He continued his work in zoology, and his painting, and he also branched out into psychology. Jung claimed that it was Carus, not Freud, who discovered the unconscious, as schematised in his book of 1846 Psyche: Zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der Seele (‘Psyche: On the Development of the Soul’).

At the age of 38, he was appointed Hofmedicus und Medicinalrath, or court physician, to the king of Saxony, and began writing accounts of his travels around Europe as part of the Saxon court, along with four long volumes of memoirs. He was awarded a prize by the Institut de France for his work on the circulatory system of insects. He seemed to excel at all subjects. But he published quickly, often at great length and with varying degrees of precision. His books are ‘islands of visionary insight’, the historian of science Franz Alexander remarked, ‘surrounded by an ocean of vague and confused generalisation’.

Not even Goethe could help him with his writing. Carus met his idol in Weimar in 1821, en route to Italy, and the two corresponded for a decade. Goethe wrote about Carus’s ‘geognostic’ paintings of rock formations, and in return Carus read Howards Ehrengedächtnis, Goethe’s poem in honour of Luke Howard and his paper of 1803 on the naming of the clouds. In his Nine Letters on Landscape Painting, Carus referred to Goethe’s poem as the perfect expression of a work of art based on the ‘higher understanding’ of scientific investigation.

None of this has any obvious relevance to A View of the Sky from a Prison Window, which might have been painted by any half-competent naturalist painter with an eye for the picturesque. The exact location is unknown – perhaps the corner of a ruined church Carus sketched on one of his walks with Friedrich. It was probably painted in his studio in Dresden, which was situated in the same building as the maternity hospital of which he was by this time the director. Around the same time as A View of the Sky, he recorded the studio in a strange and spartan painting, Studio Window. It depicts another divided window, again from a wonky perspective. The bottom half of the window is obscured by a canvas which has been propped on the ledge; another, smaller painting (perhaps the one now hanging in the National Gallery) sits on an easel to the side, its face turned away from the viewer. Carus was still under the influence of Friedrich, who had offered him practical advice on painting, such as the best way to achieve the effect of moonlight (a dark glaze on everything except the moon itself). Carus made copies of paintings by Friedrich, or sought out the locations he had painted, producing works that are so close to the originals that they were often mistaken for them. When Friedrich fell out of favour, so did Carus, but he remained obscure while Friedrich’s star rose again in the early years of the 20th century.

Carus’s Nine Letters on Landscape Painting shows him shaking off Friedrich’s influence, with all its moonlight and mountain mists, in favour of a more scientific, Goethean concept of art. Perhaps this is the escape that he is staging in his painting of the prison window – a transition from gothic moodiness into the clear scientific light of day. The term ‘landscape painting’ (Landschaftsmalerei) became a bugbear for Carus: ‘There is something artisan-like about it that revolts my whole being.’ In Nine Letters on Landscape Painting, he suggested replacing it with the more noble-sounding Erdlebenbildkunst (‘Earth-life painting’). It was a fusing of science and art that would have satisfied Goethe, or Alexander von Humboldt, a regular visitor to the Dresden studio. For Carus, Erdlebenbildkunst was a matter of representing the interconnected whole of nature, which might be indicated in the smallest detail: ‘The quietest forest nook, with its diverse, thrusting vegetation, or the simplest grassy knoll, with its delicate plants, viewed against a blue haze of distance and overarched by a fragrant blue sky, will afford the most beautiful picture of earth-life.’

Carus published his study of Erdlebenbildkunst in the mid-1820s. It was followed by Zwölf Briefe über das Erdleben (‘Twelve Letters on Earth-life’), an exhaustive elaboration of his theory. Nobody took the slightest notice. The only response at the time, as Oskar Bätschmann points out, was a satirical drawing in the Munich journal Fliegende Blätter of tree roots coming to life and walking about, with the caption ‘Organic life in nature’. Similar ideas were flourishing elsewhere, however. Constable’s oil sketches of clouds, painted on Hampstead Heath, were indebted to Howard’s theory of cloud formation. Monet’s records of changing light conditions and Seurat’s scientific approach to colour mixing were both, in their own way, ‘Earth-life painting’ – even Cézanne might be understood in those terms.

Carus was a pioneer, but also a dilettante and an idealist who couldn’t renounce Romanticism. Towards the end of his life, he gave a lecture titled Weiteres über den Gorilla und gegen die Hypothese Darwin’s (‘Further Remarks on the Gorilla and in Opposition to Darwin’s Hypothesis’), arguing on aesthetic grounds that humans couldn’t be related to gorillas, with their ‘gawking, narrow eyes’. And when it came to Howard’s naming of the clouds, it wasn’t so much the observable forms of cirrus and stratus that he cared about, which are hardly clear in A View of the Sky from a Prison Window, but rather painting as a metaphor for an unceasingly curious, observing mind, dividing the sky in four with thick brushmarks and saying this cloud is called this, that cloud is called that.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.