We are looking at a broad, empty suburban street, plenty of trees, houses set well back from the road. You might guess it was America, and the reviews tell you it’s Detroit. The movie itself isn’t saying. A girl suddenly runs out of one of the houses, looking backwards, obviously terrified. She is wearing only a slip and pants, and high heels – a nice touch. Her father appears at the door, asking what the matter is. She says she’s fine, although she manifestly isn’t. She dashes back into the house, comes out again with her handbag, gets into the family car and drives off. The next shot shows her sitting on a beach, illuminated by the car’s headlights, her shoeless feet digging into the sand. She calls her father on her cellphone, crying, says she loves him and her mother no matter what happens. In the next shot she is dead, her leg broken upwards at an impossible angle, the heel of her shoe pointing at the night sky like an exclamation mark.

For a moment we thought we knew where we were, and we (or I) had the father pegged as the villain. But he was on the phone not on the beach, and the next scene shows us another girl and another time. The two are blonde, American, vulnerable, and belong to the same teenage movie population. But they are different, and played by different actresses (Bailey Spry and Maika Monroe). The movie tells the story of this second girl, Jay. So was this scary start a prelude to our main tale, or its conclusion, to which we are about to return through a long narrative flashback? Neither, as it happens, and once we realise this we stop pretending we know what sort of film this is, and we wait and see.

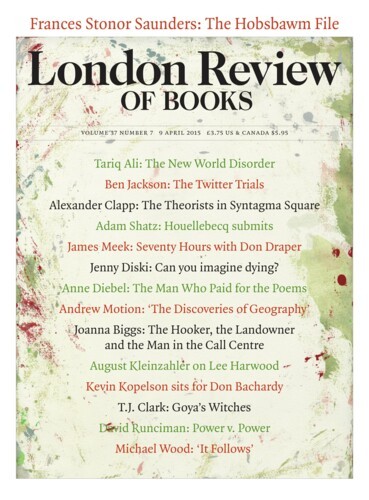

It Follows, written and directed by David Robert Mitchell, offers an extraordinary mixture of over and under-statement, with almost nothing in between. In the scene I have just described, and indeed throughout the movie, the soundtrack, composed by an outfit called Disasterpeace, crashes and thumps consistently with intimations of violence and horror – well, not intimations, but blatant, unrefusable announcements. Since nothing short of the apocalypse could be as apocalyptic as what seems to be at hand, our only question is what sort of actual anticlimax awaits, and Mitchell gives us a series of brilliant answers and evasions.

Anthony Lane thinks the film belongs to a ‘distinct genre: slacker-horror’. But then his criticism of ‘its dazed and aimless air’ comes off as a sort of baffled praise, and I certainly incline to the praise. How can an apparently casual and incoherent movie hang together in such a satisfactory way? One answer is its combination of announcement and fulfilment, and the creation of a space between them where a sort of disappointment (is that all?) turns into a kind of haunting (is it still here?).

The title works in much the same way as the music. Its pun seems too loud and obvious – we can’t wait for the next instalment, no doubt called Non Sequitur. Yes, it follows from certain acts that certain things will happen to you, consequences exist. And it literally, erratically follows you as you try to live your life – ‘it’ being the creepy personification of those consequences, a naked woman dripping blood, an old lady in a nightdress, a naked man on a roof. Is everyone followed by such figures? No, but the girl at the beginning was, and the figure did more than follow her.

There are times when you might think you were watching an Enid Blyton story worked over for the Twilight Zone or Alfred Hitchcock Presents. A group of teenagers, three girls and two boys, try to solve the mystery of what is happening in their town. The case is urgent because it is happening to one of them – but only to her, and she is the only one who sees the horror movie figures. At its most ludicrous, and where it almost does get out of control, the kids who can’t see the figure try to act as if they could: to hit the unseen creature with a chair, or repeatedly, to shoot it with a revolver. The odds on hitting one of your friends, as finally happens, rather than the target you can’t see, are totally favourable to the worst outcome, and I wondered for a while whether there wasn’t an argument about gun control in the offing. As it turns out, though, the creepy figures are not constructed any more logically than the attacks on them. Instead of scoffing at guns and threats, they are bothered, and rightly so. If they are shot they bleed; one makes a terrible inky mess of a disused swimming pool. But they can’t be killed. Mortal in one form, they are immortal in their next incarnation. I suppose this has been heard of outside of horror films.

But what lets these figures loose, or invites them into town? This is where obviousness turns to subtlety, or at least to something far less fathomable than we thought. The basic plot proposition is that sex is a sexually transmitted disease. Or just a transmitting disease, perhaps. Jay, our heroine, has a lovely evening out with her new boyfriend, ending up with consensual conjunction on the back seat of his car. It all seems blissful and banal, until, as she is dreamily waking up after a short nap, the boyfriend returns with a chloroformed rag, puts her out, and she wakes up tied to a wheelchair. He explains his problem. The last girl he had sex with passed her unearthly pursuer on to him. It can take all kinds of forms, often that of one of your loved ones – later in the film a boy is killed by a follower in the form of his mother – and it can only be disposed of by being given to another person. He has given his to her, and now he is free. It all sounds improbable, an excuse for equally pathological but more ordinary behaviour, but then Jay’s pursuer appears on cue, slowly approaching. The boyfriend helps Jay escape, but of course he can’t take away the curse he has passed on. Her next experience involves an old lady no one else can see as she plods across the school playground and along its corridors. These figures do violence, as we have seen, and sometimes they just hover; but mainly they appear and walk, slowly but persistently, after their victim or their client: they follow. This is to say that most of the announcements and premonitions end in images rather than acts, in solitary, unshakeable processions. And the film plays in very intelligent ways with our and the characters’ scepticism. Jay’s boyfriend, tracked down and forced to tell his story to the Famous Five, remembers that the passing on isn’t bound to work, and says: ‘See that girl?’ The soundtrack thunders and bumps, an eerie looking figure approaches. Jay’s friends all say yes. It was just a girl, not an apparition. Similarly, there are lots of sudden loud noises in the film. Soundtrack again, we think. No: this time, and then another time, it’s a broken window. The apparitions get up to material mischief as well as physical violence, even if their chief job is haunting.

Is the proposition then that sex is bad for you? Bad if you’re unlucky? Or perhaps that for some people every act, sexual or not, has consequences they can imagine only as horrors, as forms of vengeance or threat? Perhaps this is what being a teenager is about? To grow up is to fall into the horror movie of adult life. No, this is too reasonable and too allegorical. The film is scarier than this and its effect lies in its well-timed inconsistencies. Sex is at the heart of it all, not because it’s bad but because it’s been normalised and its mystery has taken refuge in nightmare. The movie’s affectless acting helps create this view. No one seems to feel anything except mild worry or naked fear, they don’t dream of telling their parents, they have only their ordinariness to protect them, and that turns out to be no protection at all.

This, I think, is what the opening sequence tells us. Neither a prelude nor a conclusion, it is a simple extension of the story, another version of the same thing, another part of the forest. The post-sexual nightmare doesn’t pursue everyone, but it could appear anywhere, and in the movie it does.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.