In part ten of Civilisation, Kenneth Clark turned his attention to the Enlightenment, the age of the great amateurs. These were men ‘rich and independent enough to do what they liked’, who nevertheless did things which required considerable ability, men like Lord Burlington, the architect earl. A connoisseur, an ‘arbiter of taste’, Clark explained, ‘the sort of character who these days is much despised’.* The same might be said of him, as the slight smile suggested. Civilisation, broadcast in 1969, had been filmed over the previous three years. Clark and his crew had found themselves in Paris in May 1968 in the thick of the événements. His producer, Michael Gill, recalls ‘riot police … just off-camera’, adding, laconically: ‘I was gassed.’

Despite being so apparently out of sympathy with the temper of ‘these days’, Civilisation was hugely popular. Now, when even more of what Clark stood for – connoisseurship, private patronage, direct state patronage and the life of the country house – has disappeared or is disapproved of, the Tate’s richly thoughtful exhibition Kenneth Clark: Looking for Civilisation (until 10 August) is another unlikely success. Though he was one of the most scholarly and intellectually flexible of art historians, Clark remained committed to the idea of aesthetic pleasure. Certain combinations of words, sounds and forms were his ‘chief joy and comfort’, and the sense of enjoyment is allowed full play. The first impression is of beauty and variety, from small Bow porcelain busts to drawings by Cézanne, all pieces Clark owned, commissioned or promoted. But an exhibition which has as its subject a single person who was not an artist must create its own structure and argument. A broadly biographical arrangement sweeps, as did Clark’s career, through the heart of the 20th century.

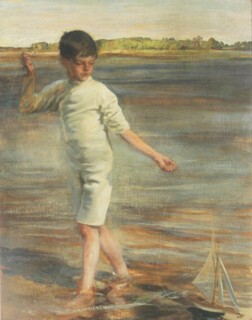

Born in 1903, the only child of wealthy parents, he first appears aged seven in a portrait by John Lavery. Solemn in white shorts, broad-brimmed hat in hand, he stands in a darkly panelled interior, a glint of sunlight on the ormolu of the clock behind. The comfortable house, the endless summer outside, it is the Edwardian childhood idyll. Clark’s claim in his notoriously unreliable autobiography that his family belonged to the idle rich and that while many were richer ‘few were more idle’ is belied by the sprinkling of works from his father’s collection. Landseer, Lavery, Charles Sims suggest that Clark began life against a background of unadventurous but serious taste in painting.

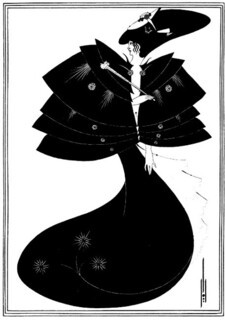

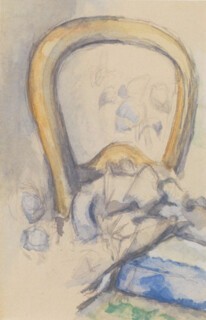

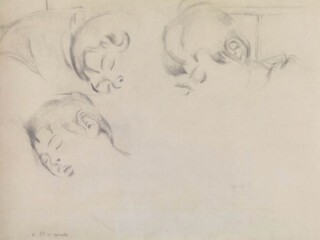

He himself was omnivorous. Japanese prints, Aubrey Beardsley and the works of Ruskin were among his early and enduring enthusiasms. Like many only children he was at ease with his parents’ generation, and his first mentors, Roger Fry and Bernard Berenson, were both forty years older than him. ‘Roger made one feel far cleverer than one was,’ Clark reflected: ‘Mr Berenson made one feel far stupider.’ From Fry he took a belief in ‘pure aesthetic sensation’ and a love of Cézanne. The exhibition includes some of the drawings he bought in France in 1933 for ‘much less than a modest motor car’; a watercolour of the back of a chair, the crumpled cloth on the seat a landscape in itself; a sheet of heads of Cézanne’s son asleep. From Berenson he learned connoisseurship, the ‘gentleman’s sport’ of attribution.

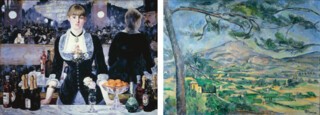

It was in 1928 that what he later called the Great Clark Boom began, with an invitation to catalogue the Leonardo drawings in the Royal Collection. From then on he was a permanent presence at the heart of the national cultural life. At thirty he became director of the National Gallery, where he caused a stir by hanging Cézanne’s Montagne Sainte-Victoire next to Manet’s Bar at the Folies-Bergère. His first book, another product of 1928, was on a quite different subject. The Gothic Revival discussed architecture that was almost universally thought ridiculous, a collection of ‘unsightly wrecks stranded upon the mudflat of Victorian taste’. Clark’s argument for considering it was that while ‘beauty is a historical document … a historical document is not necessarily beautiful.’ It was an intellectual manifesto that brought Fry’s aesthetics together with Berenson’s connoisseurship and the ‘geists’ of German art theory, with which, once the Warburg Institute was established in London in 1934, Clark was to remain closely connected. He changed his mind about Victorian Gothic, realising ‘almost too late’ that it had produced some great architecture. Yet the underlying question about taste and aesthetics that had prompted the inquiry remained: why ‘at certain times the average man can only look with pleasure at things of a certain shape and character’ was a conundrum to be profitably revolved for the rest of his life.

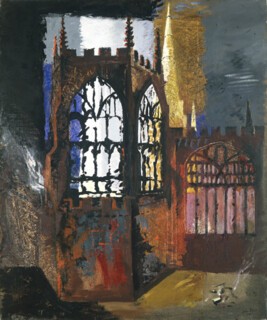

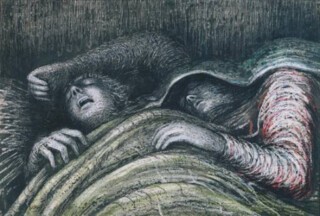

At the National Gallery during the war he compensated for the absence of the main collection, safely stowed in a disused slate mine near Blaenau Ffestiniog, by making it the venue for new work produced under the auspices of the War Artists’ Advisory Committee, of which he was chairman. It was impossible, he said, ‘to paint great events without making use of allegory’ and the new allegories – John Piper’s firelit Coventry Cathedral, Henry Moore’s shelter dwellers and Paul Nash’s Battle of Britain – were shown alongside same-size photographs of absent Gainsboroughs and Uccellos.

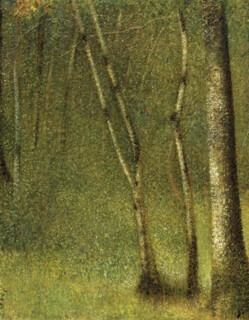

Clark’s collecting and his patronage brought together objects of ‘a shape and character’ that still please. They also surprise by juxtaposition or selection, the broad comedy of Rowlandson, the tiny, fantastical detail of Robin Ironside and the receding golds and greens of an un-obvious Seurat, The Forest at Pontaubert. His preferences trace a line through English art from Gainsborough to Lucian Freud, making a rather pointed detour round the Pre-Raphaelites but spending arguably too long in what he himself called the ‘virtuous fog’ of Bloomsbury, represented here by an Omega dinner service intended to celebrate famous women, badly painted in lugubrious hues by Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. The essence of what he believed, that art is ‘a long word which stretches from millinery to religion’, is captured in an unfinished portrait of Marie Countess of Schaumburg-Lippe by Joshua Reynolds. The face has been completed. Lost in intelligent thought, she looks just past the viewer’s eye. The rest is only blocked in except for an exquisite silver bow on the bodice. That Reynolds finished this himself before handing it over to his assistants suggests he thought it as important as the face and it makes the picture. The contrast of bright artifice with delicate flesh enhances both: the ornament, which is all surface, gives the portrait its depth.

After the war Clark became chairman of the newly established Arts Council and an enthusiastic broadcaster. By the time he made Civilisation he was presenting ideas he had developed, refined and defended over half a century, but the result is fresh. He has a better suit and worse teeth than can be seen on presenters today, but he neither patronises nor ingratiates. His firmly listed likes and even firmer dislikes – ‘lies, tanks, tear-gas, ideologies, opinion polls’, sociologists and the ‘rigidly controlled classification’ of academic specialism – make him a recognisable precursor of Jonathan Meades rather than Simon Schama. As the BBC contemplates remaking Civilisation, the exhibition shows what a hard act Clark still is to follow.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.