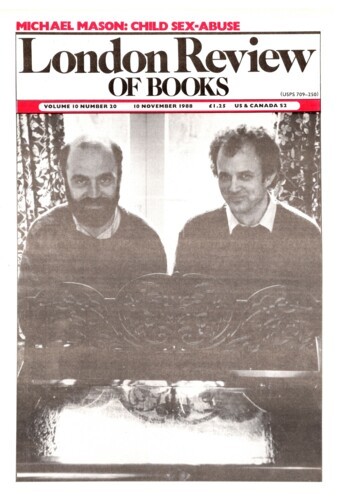

MacDiarmid and his Maker

Robert Crawford, 10 November 1988

Before 1922 Hugh MacDiarmid did not exist. And only Christopher Murray Grieve would have dared to invent him. Alan Bold’s valuable biography points out that when the 30-year-old Grieve began to write in the Scottish Chapbook under the pseudonym ‘M’Diarmid’, he was already editing the magazine under his own name, reviewing for it as ‘Martin Gillespie’, and employing himself as its Advertising Manager (and occasional contributor), ‘A.K. Laidlaw’. We tend to think of the subject of this biography as the greatest voice of modern Scottish literature; more accurately, he is the greatest chorus.