The Censor’s Scissors

Anna Aslanyan

John Heartfield was forced to leave Germany in 1933. Even before the Nazis put him on their hit list, his art had caused controversy. In 1928 he designed the cover for a book about the mores of the German top brass (Erotik und Spionage in der Etappe Gent by Heinrich Wandt). When it was banned, Heartfield produced another, turning the censor’s scissors against the censor.

PEN America has documented almost 23,000 cases of book banning in US schools since 2021. The organisers of Banned Books Week are urging people to borrow or buy a banned book (to find one, follow this map), volunteer at a library or write to the authorities. In May, the New York design firm ThoughtMatter organised Censor This! Posters were made, letters written and mailed (‘Fund schools, not book bans’), controversial words recorded (such as ‘immigrants’, ‘pregnant people’ and ‘social justice’).

Russia, too, is tightening censorship. Publishers have been coming up with ways to get round it. Roberto Carnero’s biography of Pier Paolo Pasolini came out in Russia in 2024 with large portions of the text blacked out. A new version of Eugene Onegin by the artist Blue Pencil, with most of the words obscured, is an anti-censorship gesture in the form of blackout poetry.

‘When John Heartfield and I invented photomontage – one fine day in May 1916, at five in the morning, in my Berlin studio – we couldn’t begin to imagine the great opportunities this discovery heralded,’ George Grosz remembered. The idea was already in the air: soldiers in the trenches would paste newspaper cuttings into their letters to convey things they weren’t allowed to write. While Heartfield perfected photomontage, Grosz returned to his pen, publishing in 1921 The Face of the Ruling Class, a collection of satirical cartoons. A hundred years later, the American artist Jeff Gates created an updated rogues’ gallery, Faces of the Republican Party.

The Librarians, directed by Kim A. Snyder and recently released in the UK, is a documentary about the crackdown on American school libraries that began in 2021 in Texas and soon spread to other states. Ordered to remove 850 books from their shelves – including They Called Themselves the KKK by Susan Campbell Bartoletti, The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank, How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi, Beloved by Toni Morrison, The Librarian of Auschwitz by Antonio Iturbe and Lawn Boy by Jonathan Evison – several librarians resisted. Some were fired; some received death threats. At one point in the film, a grandfather turns up at a school meeting with a gun to tell the library supporters: ‘We know what you do. We know where you live.’

The Librarians intercuts footage of the 1933 Nazi book burnings with similar scenes filmed in Tennessee in 2022. ‘The only people this is going to hurt are kids,’ one librarian, Nancy Jo Lambert, says of the ban. Another, Julie Miller, talks about losing her job ‘for asking questions’ about why the books were blacklisted.

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood unsurprisingly made the list. Last month, on learning that the novel had been banned in Canada, Atwood spoke up. Her very, very short story about two ‘very, very good children’ who ‘grew up and married each other, and produced five perfect children without ever having sex’ went viral, and eventually the authorities revised their policy.

Atwood asked why her novel was banned: ‘Because it portrays evil? Because [it] rewrites the Bible? … Because it has sex in it, even though it’s not sexy sex? … Because it has head coverings?’ Interviewed at the American Library Association annual conference, the author Tiffany Jackson suggested one reason why literature is being censored: ‘Because people don’t understand it.’

In 2024 a school board in Canada shadow-banned Jude Saves the World by Ronnie Riley, a novel about a non-binary boy, described as ‘a joy-filled story’ in a storytelling blog and as ‘the worst filth’ on X. In September, Melissa McCoul was fired from Texas A&M University for including it in a children’s literature course. A student in her class had said: ‘I’m not entirely sure this is legal to be teaching.’

British institutions are not immune. Unlike in the US, where challenges are often instigated by organisations (such as Moms for Liberty, appearing in The Librarians as a strident opponent of ‘pornographic filth’), in Britain they usually come from individuals. A single complaint can lead to a book being removed from a reading list or a library. An investigation by Index on Censorship showed that it’s mainly LGBT-themed books that get challenged; another study indicated that American pro-censorship groups are beginning to influence the situation in the UK.

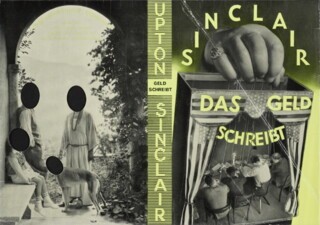

In May, when the National Endowment for the Arts withdrew funding from more than 550 organisations in the US, the cuts were described as ‘economic censorship’. There’s nothing new about that, either. In 1930, the radical German publisher Malik-Verlag published a translation of Money Writes! by Upton Sinclair; the cover, designed by Heartfield, mocked literary mercenaries. When one of them threatened to sue, the publisher was told to ‘refrain from getting personal’. Heartfield took up his scissors, making cuts to produce an even more eloquent image. The book escaped the ban.

Comments