In 1948, George Grosz sat for a portrait by Stanley Kubrick, then a young photographer for Look magazine. Grosz sits astride a backwards desk chair in the middle of light pedestrian traffic on Fifth Avenue. Neatly dressed in a suit and shiny black shoes, with a very slight smile, Grosz looks as though he’s conquering New York, as he did Berlin. His autobiography had appeared two years before, celebrated by Edmund Wilson in the New Yorker, who compared Grosz’s new Cape Cod paintings to Dürer. German museums were starting to reacquire his older works. But Grosz was already in the midst of his slow American suicide. ‘I’m a poor wretch, that’s the simple exact truth,’ he wrote to his brother-in-law. ‘I play the “famous artist”, but behind the “fame” is a big hole … if I were to paint myself, there would be pipes with stinking liquid manure flowing – a small guitar in my welcoming arms when I open them – and maybe a bird’s nest on the left shoulder.’ The former Marshall of Dada, valued asset of the Communist Party and Weimar enfant terrible was now delving into Dale Carnegie and signing his works ‘Rockwell Grosz’ in his attempt to transform himself into a suburban squire. Bertolt Brecht had tried to lure him back to Berlin to no avail. ‘We have flowerbeds and cut the lawn ourselves with a mower,’ Grosz fired back. ‘A Winchester shotgun hangs over the fireplace, and anyone who gets too close takes one in the back. No, Bertie, I’m not coming back to lousy, shitty Europe; but thanks for the kind invitation.’

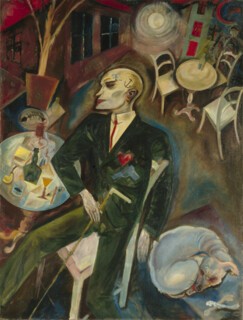

George Grosz in Berlin, at the Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart until 26 February (Covid prevented its display at the Met), reveals a different Grosz – or a version of him – seated in another chair. In Der Liebeskranke (1916), a thin, angular man sits in a nightclub after another kidney-destroying night: powdered face, shaven head with blue anchor tattooed on the cranium, gold earring, red lipstick on the mouth, in a green suit, with Grosz’s tell-tale cane between his legs. The choice before him is a syringe on the table and a gun resting on his chest below a Valentine heart. This is the Grosz who careened through Berlin in the teens and 1920s. Friends remember him – when he wasn’t acting out his alter egos as a Dutch businessman, a boxer, American doctor, Count Ehrenfried – as a habitué of the Café des Westens, with a white-powdered face and red lipstick (no tattoo, no earring; the cane was crowned with an ivory skull).

Looking at these works, it’s clear how much our image of Weimar Berlin has been coloured by Grosz’s vision. The signature types of the age are the ones Grosz picked out from it, or at least propagated most widely and ruthlessly: rabid Prussian officers with cinder-block jaws and whips; lecherous profiteers with carp mouths and beady eyes; shrivelled, reptilian intellectuals; bursting women redundantly flaunting their wares; misshapen workers and crippled veterans all but begging for extinction. This was, of course, not the only side of Weimar. Yet even at the height of Grosz’s communist commitment, the optimism of the era is evacuated. Advances for women appear limited to ways of being cut up; gatherings of people tend to look like rehearsals for Hell; there are barely any children, except Pfennig-less, balding ones.

When Grosz’s contemporaries looked at his work they saw their world reflected back at them, realer than real. ‘Since they were extreme, I regarded them as Truth,’ Elias Canetti wrote of Grosz’s pictures. ‘I didn’t see a single communist in blue overalls,’ Walter Benjamin wrote of his trip to Moscow in 1926, ‘but I did see some guys who could fit in any George Grosz album.’ ‘George Grosz’s caricatures are actually not satire but realistic reportage,’ Hannah Arendt wrote. ‘We know these types. They live all around us.’

In our own time, Grosz’s great theme – the domestic horror show of bourgeoisie – seems to have vanished as a subject, or perhaps it’s just got better at camouflage. But once you’ve seen Grosz’s types, they start popping up everywhere. Perry Anderson described Trump’s entourage of bankers, businessmen and generals as ‘a cabinet out of George Grosz’. In J.M. Coetzee’s Disgrace, the professor-protagonist considers a tangle of clothes on the floor, brushing aside the thought that he may have just raped one of his students: ‘After the storm, he thinks: straight out of George Grosz.’ In Pasolini’s Porcile, the industrialist Herr Klotz lies in bed, worried he’s losing his son to left-wing radicalism. ‘The days of Grosz and Brecht are not yet over,’ he laments to his wife. ‘I could easily have been drawn by Grosz as a sad pig and you a sad sow, at the dinner table, of course. Me with a secretary’s bum on my knee and you with your hands between the driver’s legs.’ Just before the Ukraine war began, I was sitting with friends in the Berlin restaurant Borchardt when the former SPD chancellor Gerhard Schröder – red-faced, glutinous eyes, an ecstatic rictus – trundled through the room, glad-handing his shrinking circle of comrades: pure Grosz! How much fun the Dadamarshall would have had with today’s handkerchief populists, cam girls (and their patrons), crypto grifters, MAGA warriors, Davosmen, effective altruists and Rheinmetall and Raytheon vice presidents. That is, if Grosz had stayed Grosz.

The exhibition tracks Grosz’s movement through – or absorption of – Europe’s interwar art movements: Dada, communist agitprop, Surrealism, the Neue Sachlichkeit (which Grosz thought was ‘worthless’): he could do all the voices. Grosz had lived in the workers’ district of Wedding in Berlin as a child, but only got to know the city properly during the First World War, the worst of which he was spared thanks to a series of nervous disorders (the details of his official discharge remain murky). As a boy he instinctively hated Prussian militarism and loved naked women. What distinguishes his drawings from the more dogmatic anti-militarists is the wheezing black thrill and delirious triumph he takes in depicting the madness around him – the sheer fecundity of his misanthropy. ‘People are swine’ was the closest thing Grosz had to a motto (until he replaced it in America with ‘Hurt nobody, please everybody’).

It’s little wonder that Grosz has been more beloved by writers than by fellow painters. He liked to amuse his friends with songs and funny captions. ‘The war did me a lot of good, like a spa’ is the line under a drawing of the skeleton of a German soldier clutching a rifle. ‘Fit for Active Service’ is the title of a doctor listening to the pulse of another dead man. After the war, Grosz repeatedly came before Weimar courts for breaking blasphemy laws. When a series of drawings he did for a performance of The Good Soldier Švejk included a crucified Jesus Christ wearing a gas mask and wellingtons, he narrowly escaped a prison sentence. He had fared a bit better when he was hauled in for the scandalous drawings that appeared in his lithograph collection Ecce Homo, one of the centrepieces of the Stuttgart show. Lustmord in der Ackerstrasse, which depicts a decapitated woman on a table with the killer washing his hands was less of a concern for the authorities: it revealed no pubic hair, so was legally in the clear. As the curators note in one of their placards, Germany still has blasphemy laws on the books.

It’s been Grosz’s strange fate that some of his most prominent defenders have been contemporary liberals, who take him to be too good an artist for ideology, too incorrigibly honest for the communist claptrap he sometimes spouted during his membership of the German Communist Party. In the catalogue for George Grosz in Berlin, Ian Buruma writes that he was a ‘great poseur’ and that his communist phase is best understood as just another of his acts: not for a moment was Grosz ‘driven by a need to capture the exploitation of the proletariat on paper’. Like Bob Dylan, Buruma writes, Grosz moved quickly from being a protest artist to a ‘song and dance man’. In his little book on Grosz, Mario Vargas Llosa similarly claims him for liberalism. Like Orwell, Llosa writes, he ‘was not a social artist … Grosz’s work is born of a total authenticity.’ Advertising his new American identity in his autobiography, Grosz seemed to agree. ‘I never did participate in the worship of the masses,’ he wrote, ‘not even at the time when I toyed with political theories … My drawings had no purpose, they were just to show how ridiculous and grotesque the busy cocksure little ants were in the world surrounding me.’

An ideal place to test these assumptions turned out to be a former petrol station not far from where I live in West Berlin, which the Swiss collector and gallerist Juerg Judin has converted into the Little Grosz Museum, dedicated to small shows of the artist’s work. The current show, George Grosz Travels to Soviet Russia, is dedicated to Grosz’s 1922 trip to Moscow and Petrograd, where he was fêted as one of the most valuable Western artists. It’s not hard to see why. The man who produced The Face of the Ruling Class (1921), a savage collection of political cartoons, was also the author of aesthetic credos that perfectly anticipated the Party line. In 1920, Grosz published the short essay ‘Instead of a Biography’:

The art of today depends on the bourgeoisie and will die with it. The painter, even if unaware of it, is a cash factory, a machine for producing profit, who is used by wealthy exploiters and aesthetic jackasses so they may invest their money more or less profitably and be called, therefore, patrons of the arts. Art is, to many, a kind of flight away from this ‘vulgar’ world into a shining sphere where they may fantasise about a paradise free and clear of civil strife and factionalism.

Music to a commissar’s ears. But in Moscow, where Grosz stayed in the barracks the British army had used in its abortive attempt to quell the 1917 Revolution, he was less impressed by the reality, or so he relayed years later, in a deflationary account of the trip. He met Lenin (‘I left the squeeze of his hand in a drawer unused’), heard Trotsky speak and found Vladimir Tatlin’s blueprints for a monument to the Third International ridiculous. The drawings that Grosz produced on Soviet-approved themes are impressively uninspired. In one, workers wearily shield their eyes from a rising sun that turns out to be … a hammer and sickle. The curators at the Little Grosz Museum seem to side with the older Grosz: communism may have been a genuine passion, but the trip to Russia killed it. To underline the point, they close the show with an edition of a CIA-funded anti-communist magazine, Der Monat, in which Grosz published his Russia account many years later. (Gotcha Grosz!)

But if Grosz wasn’t an obedient Soviet, it hardly impinges on his status as a radical political artist. As the Hungarian philosopher G.M. Tamás once argued, Grosz’s rejection of glorified visions of the rosy proletarian future, with sinewy workers and golden harvests, is precisely what made him one of the few genuine Marxist painters among his peers. Grosz’s unequivocal sense that the lives of workers in industrial society were miserable and degraded meant that the last thing he wanted was the equalisation of society to the mean: the world was too rotten for that. Grosz’s Marxism expressed itself not in a positive vision but in the quality of his defiance. As Günther Anders wrote in his short biography, for Grosz, kitsch art forms and romanticism perverted reality in ways that suited the top layers of society; and what was taken as reality needed to be wrested back into contestation in the most extreme manner possible, no scene untouched. Grosz was always a shrewd assessor of the types and classes that he pilloried, with a bit of a talent for prophecy. Much earlier than his peers, he sensed that German workers were poised to become the Nazis’ prize. When he had lunch with Thomas Mann in New York in 1933, and Mann put it to him that Hitler would be out of power in six months, Grosz laughed in his face and told him he didn’t have a clue.

Grosz emigrated in January 1933. A year earlier he had told one of the anonymous Nazi paramilitaries who threatened him on the telephone: ‘Just come. I have two pistols, my wife also has two, and my friend Uli has a Basque walking stick with a bayonet! We’ll show you what’s what.’ He decamped to Long Island with his family. For money he taught art classes at the Art League in Manhattan. ‘I buried my former arrogance; a tendency towards nihilistic self-complacency was relegated to the deepest cellar of my being,’ he wrote. ‘Eventually I managed pleasant phrases and gave compliments that I only half believed. I learned how by praise one could teach the difficult skill of drawing.’ For the first few years, it seemed as though he might still have ready material at hand, ripe for exposure. The American Scene (1932) is not one of Grosz’s best paintings, but the Yale jock at the centre, with his little Hitler moustache and angry proto-Beavis face is more or less exactly how I imagine the college years of the polo-obsessed playboy Tom Buchanan from The Great Gatsby. The trouble with America for Grosz was that he struggled to read the society around him, as he freely confessed to friends. ‘There are no Kollwitz types or Zille-proletarians here,’ he wrote in 1935. ‘I exclude the so-called hobos or loafers or bums … they belong to an unorganisable anarchic stratum – more like lumpenproletariat, but mostly falsely serve as material for proving the depression because of picturesque ragged costumes and sleeping spots in entryways.’

He was living the New York of Jackson Pollock (‘Rorschach-Test-Rembrandt’) and the deafening rage for Picasso (‘Der Pi’). Max Beckman and Otto Dix were rising in critical esteem while Grosz was producing ‘postage stamp’ pictures for Esquire. He came to believe the challenge was simply to make better drawings, ‘a problem that can only be solved by me, ME, alone’. The result was a turn to nature, endless unpeopled landscapes, as the scenes of Berlin gave way to the dunes of Cape Cod. The fertile hatred had dried up in Grosz’s headlong attempt to transform himself into an American and get into the spirit of the place. ‘Nobody really needs art any more, since everybody is practising it,’ he wrote in his autobiography. ‘I really love the American optimistic belief that everything can be learned; but I don’t quite believe it.’ His friends noticed he was falling apart. ‘Rarely have I seen a person who lives with such self-destructive rage,’ Rudolf Schlichter, an old Dada comrade, reported in 1954. ‘It is a depressing spectacle to see a man whom one once cherished go to the dogs in this way.’

In 1958, Grosz visited Berlin. He played the part of a loud American businessman, delighted to be cheated by ticket sellers in Munich. He went on a bender. In a bar in West Berlin, he praised Hitler in a drunken tirade. ‘Those who knew him realised that this was his way of attacking the hypocrisy of a Germany in which no one but Hitler seemed to have been a Nazi,’ Beth Irwin Lewis writes in her 1971 biography. On his way home from Diener’s on Grolmanstrasse (still popular with the Berlin art scene), Grosz collapsed inside the entrance to his apartment. A delivery woman found him at dawn, and called to workers on the street for help removing the body.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.