At Stone Mountain

Erin L. Thompson

Ignoring the many ‘no pets’ signs, a man on the trail to the world’s largest Confederate monument was leaping from rock to rock with a ball python wrapped around his neck. I began to think I hadn’t really understood Stone Mountain at all.

It was spring 2022, and I had just published a book on the history of controversial monuments in the United States. One of its chapters told the story of Stone Mountain, Georgia. In 1914, an elderly Confederate widow dreamed of a massive memorial carved on a cliff visible from downtown Atlanta. The sculptor she recruited, Gutzon Borglum, promised hundreds of figures, but after a decade he had finished only a single head, of General Robert E. Lee. The Stone Mountain Memorial Association accused the sculptor of embezzlement, fired him and blasted his portrait of Lee off the mountain. Borglum defected back to the Union, convincing some small-town boosters in South Dakota to let him turn their plan for a few sculptures into the project that would keep him in funds for the rest of his life: Mount Rushmore.

Georgia’s governor, Marvin Griffin, bought the land in 1958. He turned it into a recreational park and arranged to finish a 58-metre frieze of three Confederate leaders – Lee, General Thomas ‘Stonewall’ Jackson and President Jefferson Davis – who now ride along the cliff.

I had written my book during lockdown and was only now making my first visit to the site. I wanted to see what the activists who had begun to call for changes at Stone Mountain during the Black Lives Matter protests were up against.

The trail from the car park runs for a mile over slabs of rock through loblolly pines. It’s uneven but easy until close to the top, where the mountain humps up two steep shoulders. It was busy with people. ‘Too many breaks,’ I overheard a teenager chiding his family. They ignored him and flopped down on the rocks near where I, too, was resting.

More than a century earlier, on Thanksgiving night 1915, a group of men had climbed this path by flashlight. At the summit, they dressed in bedsheet robes and pointed hoods, set fire to a kerosene-soaked cross made of pine boards, and took their initiation oaths in the reborn Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. For those men, too, I realised, sitting on my boulder, watching the groups around me, the climb must have been a bonding exercise.

The top of the mountain is pitted with shallow pools. Fringed with yellow pollen and spilled popcorn, they are home to an endangered species of fairy shrimp. Klansmen held annual rallies here until the state took over the land. After that, they moved downhill to burn their crosses on private land below the mountain until the early 1990s.

The Confederate monument on the cliff face isn’t visible from the trail or the mountaintop. To see it, I went back down and paid the entry fee for the amusement park at the base. An animatronic T-Rex roared and jerked into periodic action beside the path. I rounded an undersized brachiosaurus to make my way into Memorial Hall, which houses an exhibition on the history of the carving.

The building has the carpeted deadness of an unpopular conference hotel. Several display cases had burnt-out lights; some of the artefacts inside had tipped over. In an auditorium, a Ken Burns knock-off documentary about the Civil War in Georgia features artificially grainy footage of re-enactors and unbearable amounts of fife and fiddle. The narrator describes the Union’s capture of the last railroad in Confederate hands as ‘the final link in the chain to shackle Atlanta’, as if the Confederacy were fighting to free itself from slavery instead of maintain it. The only acknowledgment of the cross-burnings I could find was a text at the bottom corner of a display. I had to squat to read that ‘Stone Mountain had the dubious honour of being the Klan’s “sacred soil”.’

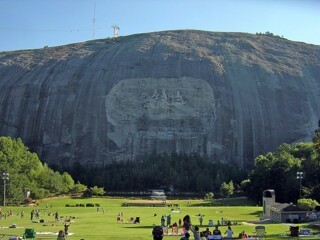

The best place to see the carving from is Memorial Lawn, a long stretch of grass directly beneath it. But even from there, the monument is surprisingly hard to make out. The carving requires regular cleaning to keep it visible, but this hasn’t been done since 2020. The Stone Mountain Memorial Association is currently dithering about whether or not to spend the half million dollars it would now take to clean it.

I looked around instead at the other people on the lawn: a young Asian woman with a tote bag and a sweatshirt denouncing the patriarchy; teenagers with purple and red hair sparring with plastic light sabres; a pair of older women with crewcuts relaxing on a tartan blanket. Families stood up to take group photographs with the indistinct monument in the background, calling out to each other in Arabic, Vietnamese, Hindi. If the three Confederate leaders could really see out over the lawn, I thought with satisfaction, they would be horrified.

But then I remembered that every low-wage worker I had encountered during the day, from Cameron, who’d taken my $20 parking fee, to Keyser, who’d sold me my lunch, was a person of colour. The composition of Georgia’s middle and even upper classes may have changed since these men rode, but the identity of the working poor has hardly shifted.

As dusk fell, a lightshow began, opening with a booming announcement of its sponsorship by an insurance company. Lasers projected from the lawn outlined Lee’s head, multiplied it, lit the heads in psychedelic colours and spun them in circles, like the Lost Cause on LSD.

An animated Dolly Parton sang. Star Wars droids skittered across the cliff. Children jumped up and danced. Three flame cannons shot ten-storey pillars of fire up into the night.

The show’s historical portion culminated with an animation of Lee riding past a burning city and a dead soldier, grimacing, drawing his sword and breaking it. The pieces of the blade tumbled around until they become the outlines of the Confederate and Union states, which then merged together. More lasers shot out to outline the Western states – electronic Manifest Destiny. The lesson seemed to be that Lee’s surrender stopped the North’s heedless destruction, reunited the Union and cleared the way for America’s present prosperity.

In 2021, the first Black chairman of the Stone Mountain Memorial Association was appointed. In 2022, the Association announced a project to revamp the displays in the moribund Memorial Hall and tell the truth about Stone Mountain – all the more important since state law currently forbids any changes to the monument itself. Perhaps visitors can reclaim the site by using it as a place for celebration and enjoyment of their own lives. But only if they know what they are ignoring.

Read more in the LRB Archive

Thomas Laqueur on the Civil War Dead

Erin L. Thompson on Iconoclasm

Amia Srinivasan on Rhodes Must Fall