Chris Marker’s Faces

Brian Dillon

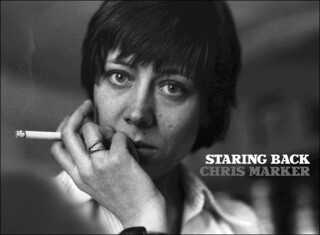

A few years ago I wrote to Chris Marker about Staring Back, a book and exhibition of his photographs. Many of the two hundred images, made across half a century, were of political protest: from demonstrations against the Algerian and Vietnam wars to marches in response to the electoral success of the National Front in 2002 and the liberalisation of French labour laws in 2006. I was hoping – rather against hope, given his well known attitude to publicity – for an interview on the subject of his portraits of protesters, maybe even a meeting at his legendarily crammed studio in Paris. A reply came back within minutes; Marker was simply too busy: ‘crushed under my present grind’. He was happy to reminisce by email about his visits to Ireland, but if I needed a thread through his imagery I would have to unspool it myself.

I wrote about the book anyway, and imagined I’d found a canny analogue for Marker’s luminously Photoshopped video grabs of young Parisian militants when I gave the piece an epigraph from Ezra Pound:

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;

Petals on a wet, black bough.

It seemed that alongside Marker’s more celebrated preoccupations with time and memory and travel – all of them now well rehearsedsince his death on 31 July at the age of 91 – had been a fascination with the private and political significance of the human face.

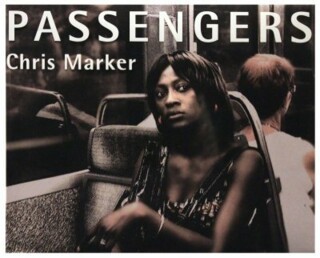

Most famously, in La Jetée, the face of a young woman glimpsed ‘in peacetime’ on the observation pier at Orly becomes the nexus for a labyrinthine meditation on memory and loss among the ruins of a post-apocalyptic Paris. (Proust is always invoked regarding that film’s hold on the past, but Marker must also have had in mind the moment in Citizen Kane when Mr Bernstein recalls a girl he saw on a ferry half a century earlier.) And in Sans Soleil, Marker tracks ‘like a hunter’ the faces of sleeping Japanese commuters and engages in a heart-stopping game of hide-and-seek with a woman in Guinea-Bissau, who eventually condescends to look at him: ‘she drops me her gaze… I see her; she sees me.’

But it’s perhaps in the lesser known films and especially the photographs that the extent of Marker’s political interest in faces is most fully expressed. (Which is not to say that he could not be whimsical too: see the photographs he commissioned or took himself for the Petite Planète guide books in the 1950s.) In Les Statues meurent aussi, which he co-directed with Alain Resnais in 1953, a young black woman stares intently into the face of an African mask in a Western museum. For his 1959 book Coréennes he interviewed and photographed North Korean workers.

It’s this strand in his work that Marker pursued in the last decade of his life, extracting stills from his video footage of Parisian street protests and travellers on the Metro. At times his enthusiasm for the smears and haloes of Photoshop made the photographs look dated in the wrong sense, and his analogies with Old Master paintings could seem forced; but in an age when young protesters were routinely accused of solipsism or a lack of historical perspective, Marker was convinced that there was ‘something special in the solitude of contemporary youngsters’.

Some time after I wrote about the photographs in Staring Back, an email and an essay arrived from Marker. I had been right about ‘In a Station of the Metro’. When he planned the book and exhibition, he wrote, he had scribbled the lines from Pound in a notebook but abandoned the epigraph as ‘pretentious’. Reading it at the top of my review, he said he ‘was thunderstruck. So it was true, after all, there existed such a thing as poetry, whose ways are by nature different from the ways of the world, that makes one see what was kept hidden, and hear what was kept silent.’