Sylvia Plath was scared of letters. The postman always announced his presence with a ‘burst of prophetic whistling’. In May 1958, eating a slice of toast with butter and strawberry jam before going to teach her class at Smith, she spotted the mailman with ‘a handful of flannel: circulars – soap-coupons, Sears sales, a letter from mother of stale news she’d already relayed over the phone, a card from Oscar Williams inviting us to a cocktail party in New York on the impossible last day of my classes. No news.’ In late 1959, waiting for short story acceptances that would not come, she wrote in her journal: ‘Must not wait for mail as it ruins the day.’ Then the next day: ‘No mail. Who am I? Why should a poet be a novelist? Why not?’ Then, in late 1962, after she’d torn the phoneline out of the wall during an argument with her husband, Ted Hughes, and he had left her and their two infant children in Devon, there were only letters. ‘I am fine,’ she wrote to her mother in America. ‘Just need a settled nanny & to rest & write & letters. I love & live for letters.’

Letters never seem to arrive at the right time: a lover’s letters come too slowly, a mother’s too quickly. A card from Knopf, ‘the usual about receiving the ms’, was nice, but rejections from the ‘disdainful New Yorker’ came in twos. Plath wrote letters in an era when paper and ink still made things happen. You might send a telegram or pick up the phone for the birth of a grandchild, but you used letters to give news of a poem accepted, to send a cheque, to seduce a boy. We have known that Plath was an avid, and not quite truthful, correspondent since 1975, when her mother, Aurelia, published an edited selection of her letters home to counter the impression left by the publication of The Bell Jar. Could the bright, reassuring, can-do ‘Sivvy’ who wrote to her ‘Dearest Mum’, also be Esther Greenwood, for whom vodka ‘went straight down into my stomach like a sword-swallower’s sword and made me feel powerful and god-like’?

After Anne Stevenson’s, Janet Malcolm’s and Jacqueline Rose’s battles to get the archives opened, and the passing of the copyright to Frieda Hughes, Sylvia’s daughter, we now have the unabridged journals, the restored text of Ariel and these two new volumes of all her known extant letters, and can finally see Plath in the round. Better than that, we can let her narrate her life in her own words. Virtually no writer in the 20th century has had their life (or rather their death) reshaped over and over again for fifty years in the way Plath’s has been. For a writer best known for being dead – when I got my Collected Plath at 17 from my parents at Christmas, I wondered how she could have killed herself by putting her head in an electric oven, the only kind I’d ever known – she is more alive than most writers apparently en vie. Extracts from these letters were serialised ahead of publication in the Daily Mail; the appearance of a minor, early short story next year is being treated as an event; the New York Times profiled the people who bought Plath’s possessions at Bonhams earlier this year; the Times will put almost any detail of her last days on its front page. Her extraordinary fame has also led to this extraordinary completeness. Maybe only Virginia Woolf’s diaries are comparable as a record of a woman becoming the writer she hoped but wasn’t sure she could be, though Woolf’s legend is different.

Plath grows up in Cold War America, deceived by a God who let her father die, wanting more than anything to be a writer and to marry a man who would make her feel like she had a vodka sword in her stomach, always. And she gets it when she arrives in Cambridge in 1956, meets her black marauder and marries him ‘in mother’s gift of a pink knit dress’ three and a half months later. (When I got married at 28 to the man I met at Oxford at 19, I married in pink partly under the influence of Ted and Sylvia, partly because my mother had also married, though not knowing or caring about Plath, in a pink knitted dress in 1977. I liked the resonances, then.) But the world, even when it gives her what she wants, also doesn’t. Literary success is baseless, fleeting; the marriage dissolves in betrayal, arguments, abandonment. The hard work has come to ash. Awake at 4 a.m. when the sleeping pills wear off, she finds a voice and writes the poems of her life, ones that will make her a myth like Lazarus, like Lorelei. But now she knows that her conception of her life, psychological and otherwise, is no longer tenable, and never was. Now what? ‘I love you for listening,’ Plath, abandoned and alone, tells her analyst Ruth Beuscher in a letter late in 1962. The rest of us are listening at last.

The first letter is to Plath’s father, Otto. ‘I am coming home soon,’ she told him on a visit to her maternal grandparents in February 1940 – she was seven. ‘Are you as glad as I am?’ It is also her only letter to him since he died nine months later, following complications after the amputation of a gangrenous leg: the result of undiagnosed diabetes. Aurelia moved Sylvia and her younger brother, Warren, to Wellesley, Massachusetts, so that her parents could help while she went out to work. At 13, Plath wrote to her mother from summer camp nearly every day. Always prone to losing weight, she reassured Aurelia by listing everything she ate (‘Two bowls of noodle soup, one slice of bread, two helpings of potatoes and cabbage’), updated her on her activities (‘How I love metal work!’), sent poems she’d written for the camp newspaper (‘The lake is a creature/Quiet, yet wild’), shared her accounting (blueberry sales and pocket money from grampy and grammy on one side, a sketchbook and stamps on the other) and told her she was happy over and over again, to the point that you wonder if she was.

It’s all cutely, earnestly all-American. We see her earnestness in political matters too when she wrote to a fan, Eddie Cohen, who had sought her out after reading a story she published in Seventeen the summer before she went to Smith. ‘I consider my story not far from the usual Seventeen drivel,’ she wrote. ‘Why is it that my particular brand of drivel rates such subtle flattery?’ Replying to his reply, she started to flirt: ‘I like to think of myself as original and unconventional … my biggest trouble is that fellows look at me and think that no serious thought has ever troubled my little head.’ And then to worry – ‘Oh, Ed, don’t laugh at me … I’m so pathetically intense. I just can’t be any other way’ – about the politics behind Mutually Assured Destruction: ‘Even if you’re for Pacifism, you’re a communist. They are so small-minded that they can’t give anyone credit for wanting life and peace even more than world-domination. I get stared at in horror when I suggest that we are as guilty in this as Russia is; that we are warmongers too.’ Legions of teenagers, and not only teenagers, would agree.

The letters to her mother multiplied when she arrived at Smith. On 26 September 1950, two days after she got there, she wrote to her mother four times. (Is there such a thing as a helicopter child?) ‘I still can’t believe I’m a Smith Girl!’ she signed off in one; in another she recounted posing for her posture picture. ‘You have good alignment,’ she is told, ‘but you are in constant danger of falling on your face.’ She took English, art, French and botany and worried constantly about her workload, complaining that she has ‘to keep on like the White Queen to stay in the same place’. When she got a B- in her first English paper, it made her feel ‘slightly sick’. She dated with the fervour of a boy-crazy 18-year-old. ‘Oh dear will a nice freshman boy never give me a tumble?’ she sighed in a letter her mother suppressed. Sylvia Plath had to be good at everything. ‘God, let me think clearly and brightly,’ she wrote in her journal, ‘let me live, love and say it well in good sentences, let me someday see who I am.’ A farm boy gave her a ‘vehement’ kiss in the summer but she longed for more than going ‘from date to date in soggy desire’. In her ‘boyless’ state, she went to see A Streetcar Named Desire, bought ‘“Vivid” lipstick – goes beautifully with my orange top’ – drew a hot bath, took a sleeping pill and got eight hours. When she learned her scholarship had been endowed by Olive Higgins Prouty, a Smith graduate and the author of the novel Now, Voyager, she wrote home: ‘If only I’m good enough to deserve all this.’ She was studying The Mayor of Casterbridge, and trying to ‘twist out a chunk of my life and put it on paper’, as she told Prouty, under the influence of, in turn, Edna St Vincent Millay, Sinclair Lewis, Theodore Roethke, Virginia Woolf and Stephen Vincent Bénet.

When her friend Ann Davidow left Smith after one term, Plath’s first letter to her, written through tears, told her that although she’d come third in the nationwide Seventeen short story contest, ‘what the hell do I care about artificial black & white “success” if I haven’t got a soul but my own perplexed self to talk to? God, Davy, I can’t say how much I miss you.’ In her next letters to Ann, she had bucked up, and described visiting a medical student at Yale, Dick Norton, who became the model for Buddy Willard in The Bell Jar. ‘Yale junior prom! Honestly, that Dick practically floored me!’ she wrote to Ann. ‘Well, I got dressed up to kill in my old white formal, and evidently things took a quick turn from the platonic to the … well, you know.’ In her journals she fills in the dots: she let the ‘stiff white net slip to the floor’, lifted a warm cat purring to her bare breast and then to ‘bed, and again the luxury of dark. Still the blood and flesh of me were electric and singing quietly. But it ebbed and ebbed and dark and sleep and oblivion came and came, surging, surging, surging inward, lapping and drowning with no-name, no-identity, none at all.’ Later that summer, she also dated Dick’s brother Perry, though Dick had told her he’d like to marry her once he was at Harvard Medical School, a ‘let’s wait and keep our fingers crossed deal’, as she put it to Ann. She kept dating. ‘Always the dream,’ she wrote in her journal the next year, ‘loving two boys in one day differently for different times. Kissing both and loving both.’

There is a greediness to all this, a relentlessness, a desire to have it all. But only men can have it all, she wrote in her journal:

My consuming desire to mingle with road crews, sailors and soldiers, bar room regulars – to be part of a scene, anonymous, listening, recording – all is spoiled by the fact that I am a girl, a female always in danger of assault and battery … I want to talk to talk to everybody I can as deeply as I can. I want to be able to sleep in an open field, to travel west, to walk freely at night.

At 17, she had told her journal: ‘I think I would like to call myself “The girl who wanted to be God”.’ And she would retain this intensity across her whole career. When I first read Plath at 17, though I found the early poems hard to understand, and some of the later, fragmented ones too, I do remember the rush, feeling more than knowing that this was the real thing. ‘Daddy’ shouldn’t work: who could write a poem about fathers and husbands and Nazis and pretty red hearts, about Freud and Viennese beer and the Nauset beaches? Who would? Yet she pulls it off, and we are slack-jawed and mildly horrified. Marianne Moore would say that she is ‘too unrelenting’ in The Colossus, her first book of poems; Robert Lowell would put the same thought another way by saying that in Ariel she was playing ‘Russian Roulette with six cartridges in the cylinder’. I also remember feeling that I was liking something that it was a cliché for me to like. I thought she was for girls like me who were told that they thought too much. As well as a reminder that being like that was dangerous. (My brother regularly threatened to buy me a kitten to cheer me up when I was writing this piece. He’d read The Bell Jar.)

Dick was ‘out’ soon enough, and other boys in, like Myron Lotz, for whom she writes the villanelle ‘Mad Girl’s Love Song’: ‘I shut my eyes and the world drops dead/I lift my lids and all is born again/(I think I made you up inside my head.)’ This poem, one of Plath’s early favourites, is not in the Collected, and one of the things these letters makes clear is that we need a Complete Poems – Hughes left much of the early work out of the Pulitzer-winning volume. Her resistance to her mother was growing. Aurelia, she told her brother, ‘is an abnormally altruistic person, and I have realised lately that we have to fight against her selflessness as we would fight against a deadly disease’. The ‘great god Gordon’ Lameyer, a tall, handsome, American-jawed – I might as well say it – hunk, arrived in spring 1953, along with acceptances of three poems by Harper’s (though they didn’t take ‘Mad Girl’s Love Song’), and the news that she had won a stint as guest editor at Mademoiselle in New York that June. In NYC she saw Tanaquil Le Clercq dance Balanchine, got ptomaine poisoning (which had her wanting ‘to die very badly for a day’) and interviewed Marianne Moore. By July, she was back home, and writing Joycean love letters to Gordon, who had joined the navy. Her letter prose, usually loose and chatty, was becoming show-offy, swirling with in-jokes. But in her journal, she documented her disappointment at not being accepted for Frank O’Connor’s writing seminar at Harvard as it leaked into every area of her life, and into her sentences, which flicker between the first and second person:

You looked around and saw everybody either married or busy and happy and thinking and being creative, and you felt scared, sick, lethargic, worst of all, not wanting to cope. You saw visions of yourself in a strait jacket, and a drain on the family, murdering your mother in actuality, killing the edifice of love and respect – built up over the years in the hearts of other people … Fear, big & ugly & snivelling. Fear of not succeeding intellectually and academically: the worst blow to security. Fear of failing to live up to the fast & furious prize-winning pace of these last years – and any kind of creative life. Perverse desire to retreat into not caring. I am incapable of loving or feeling now: self-induced.

She would turn this state into the image of the fig tree in The Bell Jar: Esther sits beneath it, watching all the branches of her life – romantic, intellectual, academic, editorial, maternal – grow, bear fruit, ripen, and then wither, until finally the blackened and wrinkled figs fall to her feet. ‘You are afraid of being alone with your own mind,’ she noted to herself. Her next letter to Gordon was written on the first day of outpatient electroshock treatment, though she said nothing about it. She attempted suicide on 24 August, but was found, barely alive, two days later. She received treatment – analysis, ECT, insulin shots – in Massachusetts hospitals, including McLean in Belmont, where Lowell went in some of his manic phases. ‘Mother brought up your letter,’ she wrote to Gordon a week after she was found.

I don’t know if I can ever in the world tell you how tremendously important your words were to me … you would be among the very first of my companions I would want to see … the reasons I can’t see people now are many and various – among them, that I have a few face bruises that need to heal – and of course I’ll be under doctor’s care for a while more.

From McLean she wrote to her mother on 17 December: ‘I am doing occasional work over at the library – and am having my sixth treatment tomorrow. I hope I won’t have to have many more.’ And on Christmas Day, at home with her family before returning to the hospital, she wrote to Gordon to thank him for the copy of Axel’s Castle, Edmund Wilson’s study of the Symbolist poets: ‘Your letters, which I am just now growing able to fully appreciate, have made me want, more than any other single thing, to find my way back to the world which I am again sure I can love with a deep intensity once more.’

After Christmas, she wrote a long letter to Eddie Cohen, frankly and clearly and quietly describing what had happened to her:

I was sterile, empty, unlived, and unwise, and UNREAD … I became unable to sleep; I became immune to increased doses of sleeping pills. I underwent a rather brief and traumatic experience of badly given shock treatments on an outpatient basis. Pretty soon, the only doubt in my mind was the precise time and method of committing suicide. The only alternative I could see was an eternity of hell for the rest of my life in a mental hospital, and I was going to make use of my last ounce of free choice and choose a quick clean ending.

She tried to drown herself, ‘but that didn’t work’, and then she swallowed fifty sleeping pills on ‘the dark sheltered ledge in our basement’, having left a note for her mother saying she had gone for a long walk. ‘I swallowed quantities and quantities and blissfully succumbed to the whirling blackness that I honestly believed was eternal oblivion.’ But she vomited the pills up, and was rescued when her brother heard her moans. Prouty, who had herself had a mental breakdown, paid for private treatment, which included being analysed by Ruth Beuscher. At last, Plath told Eddie, she could take pleasure in reading again. ‘I need more than anything right now what is, of course, most impossible; someone to love me, to be with me at night when I wake up in shuddering horror and fear of the cement tunnels leading down to the shock room, to comfort me with an assurance that no psychiatrist can quite manage to convey.’ She thought, she hoped, that the worst was over.

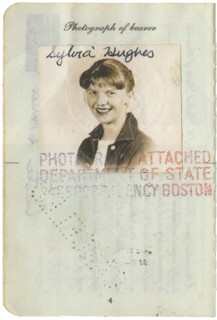

In the new year, she was back at Smith. ‘Strange, but you have become almost a mythical figure to me,’ she wrote to Gordon in May, ‘an eclectic blend of ulysses, kilroy, icarus, neptune, ishmael, noah, jonah, columbus, and richard halliburton! So you must, in all kindness, emphasise your mortal finitude when next we meet!’ He had leave in June, and it is through Gordon’s faithful eyes that we see Plath on the cover of the first volume of the letters: blonde hair, red lipstick and white bikini on creamy Massachusetts sand, alive when she could have been dead. Some have complained of objectification but I no longer see that when I look at the picture. Plath called the summer of 1954 her platinum summer, the one in which she got to be ‘a giddy gilded creature who careened around corners at the wheel of a yellow convertible and stayed up till six in the morning because the conversation and bourbonandwater were too good to terminate’, as she said, reminiscing to Gordon afterwards. After hundreds of pages of worrying that Plath is still too hard on herself, the reader feels her joy like a triumph.

She told Gordon that if she didn’t get a fellowship to Cambridge, ‘I’ll spend the summer in new york as a call girl, or, better still, you can solicit for me among your esoteric navy men!’ But soon she had a place at Newnham College on a Fulbright, and in September 1955, sent her first letter to Aurelia from England:

London is simply fantastic. So much better organised (beautiful ‘tubes’ with artistic posters, two decker red buses, maps everywhere, all black cars and cabs, guides to theatres, all posted) than NYC; more beautiful than Washington (parks with roses, pelicans, palaces, plane trees and fig trees and lakes and fountains) and infinitely more quaint and historic (obviously) than Boston. The ‘bobbies’ are all young, handsome, and exquisitely bred; I think they’ve all gone to Oxford.

She went to the British Museum and to see Waiting for Godot and loved Foyles. In Cambridge, she bought Lucy Rie pots for her rooms and threw herself into studying, dating, acting. But women to admire, and to be friends with, were scarce. At Newnham, the dons were ‘all very brilliant or learned (quite a different thing) in their specialised ways, but I feel that all their experience is secondary, and this to me is tantamount to a kind of living death.’

At the end of the year she went to Nice to meet Richard Sassoon, a Yale student she’d got to know in America the year before. He wasn’t a blond navy hunk, but French, dark and ordinary-looking in the one picture we have of him from the 1950s: he has never spoken publicly about Sylvia, and the only letters we have are the ones she kept a copy of. She had written to him with her usual seductions: ‘do you realise that the name sassoon is the most beautiful name in the world. It has lots of seas of grass en masse and persian moon alone in rococo lagoon of woodwind tune where passes the ebony monsoon … I only want the moon that sounds in a name and the son of man that bears that name.’ The Sivvy voice of the letters has often been compared with the voice in her journals to make an argument about Plath’s unstable personality, but she often sounds like her journal self in her letters to her boyfriends, and the playful way she writes to Sassoon is a relief after pages of carefully turned advertisement prose to her mother. They walked the Promenade des Anglais together, but broke up. ‘Will Richard ever need me again?’ she wondered in her journal. ‘Part of my bargain is that I will be silent until he does.’ On 20 February she wrote ‘Winter Landscape with Rooks’, one of her first mature poems: ‘What solace/can be struck from rock to make heart’s waste/grow green again? Who’d walk in this bleak place?’

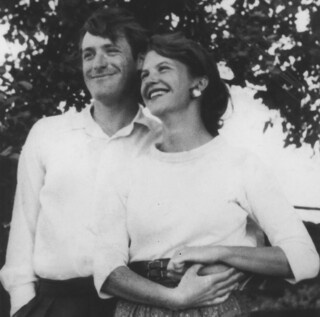

On 25 February 1956, she went to a party for the St Botolph’s Review, and ‘the worst thing happened, that big dark, hunky boy, the only one there huge enough for me … came over and was looking hard in my eyes and it was Ted Hughes.’ He snatched her red headband and kissed her; she bit him on the cheek ‘long and hard’ enough to draw blood. ‘The one man since I’ve lived who could blast Richard,’ she wrote in her journal, and noted that she had thought about her shock treatment that night. ‘Until someone can create worlds with me the way Richard can,’ she told her mother a fortnight later, ‘I am essentially unavailable’; ‘Pursuit’, her first poem about Ted, was enclosed: ‘There is a panther stalks me down/One day I’ll have my death of him.’ A week after that, she told Aurelia: ‘Gordon has the body but Richard has the soul. And I live in both worlds.’ But by April she had chosen: ‘I have never known anything like it: for the first time in my life I can use all my knowing and laughing and force and writing to the hilt all the time, everything.’ On Bloomsday, they were married in Bloomsbury. Sylvia was 23, and the plan was set:

He is going to be a brilliant poet … I shall be one of the few women poets in the world who is fully a rejoicing woman, not a bitter or frustrated or warped man-imitator, which ruins most of them in the end. I am a woman, and glad of it, and my songs shall be of fertility of the earth and the people in it through waste, sorrow and death.

There is a moment in Tess of the D’Urbervilles when Hardy has Tess notice that among all the days of the year that mean something to her, there is one ‘which lay sly and unseen’, the one on which she’ll die: ‘Why did she not feel the chill of each yearly encounter with such a cold relation?’ Reading Plath’s letters, you feel the chill. Her birthday is 27 October, her wedding day 16 June, the day of the St Botolph’s Review party 25 February, Ted’s birthday 17 August, Frieda’s 1 April, Nick’s 17 January and the day she would die 11 February 1963. When she meets Ted – which is not the same as saying it is his fault – her death comes into view. He first drew her horoscope four and a half months into the marriage. Sylvia had ‘Mars in 24 of Leo, and the last degree of Aquarius rising, with Saturn in 29 of Capricorn, on the cusp of the 12th, which is suicidal – especially opposite Mars in the 6th. All Correct.’ The Hugheses also liked to commune with spirits using a Ouija board (they mostly asked which poems of theirs would be accepted, though the spirits did once tell Plath to write about Lorelei, whose song in German legend lures men to their death). They believed in fate, even if we don’t.

The Plath-Hughes marriage doesn’t at first seem damned. They honeymooned in pre-package holiday Benidorm, going to the market in the morning, making love in the afternoon, reading and writing at night. Plath returned to Cambridge to finish her degree, and fearful that her marriage would mean the withdrawal of her Fulbright grant, got Ted to stay away. Poetry took her love poems: a good omen. ‘We shall be living proof that great writing comes from a pure, faithful, joyous creative bed. I love you; I will live like an intellectual nun without you; I need no one but you,’ she wrote to him in a letter that also detailed her errands and the conversation over the dinner table at Newnham. On the same day he wrote with two plots for short stories, an account of reading Wallace Stevens aloud and an admission: ‘I neglected you. That’s one of my most tormenting thoughts that I didn’t suck and lick and nibble you all night long and it’s a thought I shall never let myself in for again once I’ve had the chance to mend it.’ On one of the plots, she commented: ‘Obviously she doesn’t love her husband. She should delight to be raped on the floor.’

Theirs was a fusional marriage: emotionally, physically, editorially. Ted queried the word ‘clear-cut’ in a new poem of Sylvia’s, but added: ‘There’s a terrific interplay of images and movement, – it “comes off” – vile phrase – perfectly.’ She sent him details of poetry contests he should enter. They complained about editors; about one who says an animal story of Ted’s is ‘abstract in conception’, Sylvia said: ‘Well, what, for god’s sake isn’t?’ and she fantasised about the New Yorker begging them for poems. ‘I am simply sick, physically sick without you; I cry; I lay my head on the floor; I choke, hate eating; hate sleeping, or going to bed,’ Sylvia wrote. ‘I feel so mere and fractional without you,’ she added when she couldn’t stand it any longer, and proposed confessing to the Fulbright commission what they’d done. ‘I am married to you & I would work & write best in living with you. I waste so much strength in simply fighting my tears for you.’ Ted agreed: ‘To spend our first year – which is longer than most marriages last anyway – apart seems mad … I can hardly remember you without feeling almost sick and getting aching erections. I shall pour all this into you on Saturday and fill you and fill myself with you and kill myself on you.’ He moved back to Cambridge.

As she worked towards her finals, they lived in rooms in Eltisley Avenue, painting the first walls of their married life pale blue and raging about the ‘old smug commercial colonialism’ of the Tories when the British bombed Egypt during the Suez Crisis. The winter seemed long. They were remarkably free of writerly jealousy; when The Hawk in the Rain won the Harper’s poetry prize, she wrote to her brother that ‘I always wanted a man to look up to – and now, you will understand, how much easier it will be for me when one of mine gets accepted – having him there first.’ Ted believed that ‘Sylvia is my luck completely.’ She baked her disappointment at rejections into orange chiffon pies and started writing a novel about Cambridge. ‘My life,’ she wrote in her journal, ‘will not be lived until there are novels and stories which relive it perpetually in time.’ They moved to America so that Plath could take up a job teaching English at Smith, but she was soon exhausted by working, and miserable that she didn’t have enough time to write. She read instead: James, Woolf (‘I shall go better than she. No children until I have done it’) and Lawrence: ‘Why do I feel I would have known & loved Lawrence – how many women must think this and be wrong!’ They had a lot of morning sex.

In June 1958, she had her first poem accepted by the New Yorker. ‘Mussel-Hunter at Rock Harbour’ moves from the perspective of the hunter to that of the hunted, ‘dull blue and/Conspicuous’. She argued with the editor to have ‘river’s/Backtracking tail’ instead of ‘backtrack tail’ but accepted the commas he added: she wasn’t an angry or fussy proofreader of her own work. The poem’s acceptance was an encouraging way to embark on her first year of living by her writing, a year in which she was also being analysed by Beuscher again and trying to get pregnant. She and Ted brought home a baby bird from a walk in a Boston park one day, but when the diet of milk and raw ground steak failed to build the bird up, Ted gassed it in a shoebox; one of their two goldfish died and the other was set free in a Boston pond; you fear for Sappho, the kitten they adopted. When Sylvia became pregnant, they decided to come back to England, moving into a flat in Chalcot Square in North London in January 1960. Frieda was born at home and had her first bath in Sylvia’s biggest pyrex dish. ‘I don’t know when I’ve been so happy,’ she wrote home. Ted had held a mirror so she could see Frieda being born, and wrote to a friend that the birth was short because of his ‘hypnotisings. For the past month I’ve been putting her to sleep at nights – telling her to lose her toes, release her feet, so on, up her body, telling her … to relax & relax & relax & relax & that she’s going to have an easy short delivery.’ Much of the Hugheses’ courting of magic was also a warding-off of danger: Sylvia with cake, Ted with meditation.

The poems Sylvia wrote that year were, she insisted, ‘bagatelles, light verse, not poems’, though the New Yorker liked them. They accepted ‘Two Campers in Cloud Country’, based on a moment from a road trip they’d made the summer before. Away from the ‘labelled elms, the tame tea-roses’, in a landscape of ‘man-shaming’ clouds, ‘it is comfortable, for a change, to mean so little.’ Plath never worried about the climate in the way we do, but she read Rachel Carson’s early work about the sea, and the natural world – elm and laburnum trees, blackberry bushes, poppies, the moon – appears again and again in the late poems. The Colossus was published in London, a week after her 28th birthday. Day to day Ted looked after Frieda, their ‘living mutually created poem’, in the mornings so that she could work, mostly on The Bell Jar, and in the afternoons she took the baby so that he could write. (At the beginning of their marriage, they shared a writing table; her Rombauer – the American classic The Joy of Cooking – at his elbow; her copy of Le Rouge et le noir next to his anthology of Spanish poetry.) Ted later told their son, Nick, that this period of their marriage was like ‘living inside a Damart sock’.

Early in 1961 there was a miniature burst of creativity, presaging the one that would last for the final six months of her life. In a ‘low mid-winter slump’, Plath miscarried her second pregnancy on 6 February. (In a letter written late in 1962, Plath would tell Beuscher that Ted ‘beat me up physically’ a couple of days before the miscarriage.) ‘I am as sorry about disappointing you as anything else,’ she told her mother, but took solace in Frieda’s lalala, in typing Ted’s play and in the Bergman movies they were showing at the Everyman in Hampstead. ‘We’ve had a sprinkling of clear invigorating blue days this week & I’ve had Frieda out in the park while I sat on a bench and read this week’s New Yorker,’ she wrote to her mother on 9 and 10 February. On the 11th, she wrote ‘Parliament Hill Fields’: ‘Your absence is inconspicuous;/Nobody can tell what I lack,’ the first stanza ends. The speaker’s winter walk home takes in a crocodile of small girls, a pink plastic barrette, a cloudbank, ‘I suppose it’s pointless to think of you at all,’ writhen trees, the moon’s whitening crook, blueing hills and finally the lit house. In ‘Two Campers’ the landscape pressed in on the poet, turning her into a fossil; here the poet’s mood makes every forgotten hairclip significant. A nature poem has become a Romantic meditation. ‘The old dregs, the old difficulties take me to wife.’

In March, she had her appendix out. She was brought orange juice, milk and steak sandwiches by Ted every day: ‘He is an absolute angel,’ Sylvia wrote to her mother. ‘To see him come in at visiting times, about twice as tall as all the little stumpy people with his handsome kind smiling face is the most beautiful sight in the world to me.’ On her first night in hospital he also brought a letter from the New Yorker proposing she have a ‘First Reading’ contract with the magazine. ‘I had to laugh,’ Plath wrote, ‘as I send all my poems first there anyway.’ She read Agatha Christie and looked at her ‘table of flowers sent by Ted’s parents, Ted, Helga Huws & Charles Monteith, Ted’s editor at Faber’. And she listens: ‘The British have an amazing “stiff upper-lipness” – they don’t fuss or complain or whine – except in a joking way & even women in toe to shoulder casts discuss family, newspaper topics & so on with amazing resoluteness. I’ve been filling my notebook with impressions and character studies.’ In her journal, which begins with a line good enough for poetry (‘Still whole, I interest nobody’), she detailed her flowers, ‘daffodils, pink & red tulips, the hot purple & red eyed anemones … . it is like an arbour when they close me in.’ Seeing Ted had her ‘as excited & infinitely happy as in the early days of our courtship’; the date of the New Yorker letter ‘was that of our first meeting at the Botolph party five years ago’. She now had an editor who would listen, the love of her husband and daughter, her mother’s altruism at a safe distance, support from friends in London and nearly three weeks in an NHS bed to recover. The Saturday after she left hospital, she wrote ‘Tulips’:

I didn’t want any flowers, I only wanted

To lie with my hands turned up and be utterly empty.

How free it is, you have no idea how free –––

The peacefulness is so big it dazes you,

And it asks nothing, a name tag, a few trinkets.

It is what the dead close on, finally; I imagine them

Shutting their mouths on it, like a Communion tablet.

All the other flowers have disappeared and the red tulips remain, ‘too excitable’ against the whiteness of the sheets and walls. Seeing that the letters are banal and the journal intense makes ‘Tulips’ more mysterious still: we have all there is to have, and we still can’t see quite how she’s done it. But she knew she had: the New Yorker took the poem and she herself sent it to Theodore Roethke, whom she’d met earlier in the year and imitated in ‘Poem for a Birthday’, the climax of The Colossus. She would also draw on the hospital atmosphere for ‘Three Women’, her short verse sketch. Knopf soon accepted The Colossus for publication in America – she was no longer simply the poet’s wife.

Plath and Hughes decided to move to Devon, where they found a thatched cottage (with no central heating) called Court Green in the village of North Tawton. The idea was to escape from Ted’s fame in London, to be close to nature, to save money on rent by buying and to have space for separate studies and their many babies (another was due in January). They placed an ad in the Evening Standard to sublet Chalcot Square, and tore up the cheque of the ‘chill busybody man’ who got there first in favour of another couple, ‘the boy a young Canadian poet, the girl a German-Russian whom we identified with, as they were too slow and polite to speak up … the couple are coming to supper this week.’ The couple was David and Assia Wevill.

In September they moved and began furnishing their fourth home in as many years. It turned cold, another record-breaking winter, and it was months until they could afford carpets. ‘I am dying for a Bendix!’ Sylvia wrote to her mother, complaining about the washing, and her mother found money for an American machine. (She also made her mother send over American vitamins, American Maidenform bras, American cake mix.) Ted carpentered Frieda a doll crib for a Christmas present, and Sylvia painted it with hearts and flowers. The ‘repulsive shelter craze’ made her wonder to her mother ‘if there was any point in trying to bring up children in such a mad self-destructive world’. Nick was born in January, with a ‘black frown’ which relaxed into the Hughes ‘handsome male head with a back brain-shelf’. She began reviewing for Karl Miller at the New Statesman, won the Guinness Prize for ‘Insomniac’ and a $2000 Saxton Grant for The Bell Jar, which she planned to dedicate to her analyst. ‘I would love to have the dedication to R.B.,’ Beuscher replied. ‘I have often thought, if I “cure” no one else in my whole career, you are enough.’ In a letter to her London publisher, she defended the novel from ‘the libel issue’: ‘Buddy Willard is based on a real boy – but I think indistinguishable from all the blond, blue-eyed boys who have ever gone to Yale. There are millions, and hundreds who become doctors. And who have affairs with people.’ She attended the local church, crossly – the Trinity was ‘a man’s notion, substituting the holy ghost where the mother should be’ – and befriended her midwife, Winifred Davies. ‘I find myself liking baby talk,’ she told Marty, ‘but I miss the other things ––– notions, ideas, I don’t know what.’ In spring, the bank bloomed yellow with daffodils.

But in early July, she picked up the phone to a woman’s voice: ‘Can I see you?’ Ted said he had no idea who it was. ‘I was pretty sure who it was,’ Sylvia wrote to Beuscher.

A girl who works in an ad agency in London, very sophisticated, and who, with her second poet-husband, took over the lease on our London flat. We’d had them down for a weekend, and I’d walked in on them (Ted & she) tête-à-tête in the kitchen & Ted had shot me a look of pure hate. She smiled & stared at me curiously the rest of the weekend.

After a sleepless night and ‘horrid talk (me asking him for god’s sake to say who it was so that it would stop being Everybody), he took the train to London for a “holiday”.’ Ted told Sylvia he loved her and the children, would come back and hadn’t ‘touched another woman since we were married. I have discontinued the phone, for I can’t stand waiting, every minute, to hear that girl breathing at the end of it, my voice at her fingertips, my life & happiness on her plate.’ Sylvia’s idea of herself and the life she was living was shattered.

I am simply not cool & sophisticated. My marriage is the centre of my being, I have given everything without reserve … I write, not in compensation, out of sorrow, but from an overflow, a surplus, of joy … I feel ugly and a fool, when I have so felt beautiful & capable of being a wonderful happy mother and wife and writing novels for fun & money. I am just sick. What can I do?

In her next letter to Beuscher, nine days later, things already seemed different. ‘What has this Weavy Asshole (her name is actually Assia Wevill) got that I haven’t … I mean I was not schooled with love for two years by my French lover for nothing … I’m damned if I am going to be a wife-mother every minute of the day.’ With the shock came exhilaration: ‘It broke a tight circuit wide open, a destructive circuit, a deadening circuit & let in a lot of pain, air and real elation. I feel very elated.’ What sort of life was she living anyway?

It is not very much consolation to me that Ted really deeply & faithfully loves me, while he follows any woman with bright hair, or an essay on Shakespeare in her pocket, or an ability for flamenco dancing … I feel if he really loved me he would see how this hurt damages my whole being, makes it barren, & deprives me of my joy in lovemaking with him.

Her next two letters were to two men she would make passes at, the critic Al Alvarez and the poet Richard Murphy.

In March this year, Frieda Hughes auctioned a number of her parents’ possessions at Bonhams. I held Sylvia’s beloved Rombauer, the binding missing from overuse, the recipes annotated in her un-joined up, childishly angular handwriting. I wondered what the underlined Shrimp Wiggle was, but wasn’t tempted to make it myself. But I had cooked like Sylvia, or rather my mother had, finding a recipe in the Guardian Weekend magazine for the Plath family tomato soup cake with vanilla frosting, and bringing it out as a surprise with candles for my 28th birthday. (Sylvia to Aurelia in September 1961: ‘How many ounces are there in an American tomato soup can you use for tomato soup cake? I didn’t think to question, but our cans seem to be bigger than yours, as my cake was a bit “wet”.’) And I had married in a Sylvia dress, with ‘love set you going’, the first half-line of ‘Morning Song’, which begins Ariel, engraved inside my wedding ring. My idea of marriage was a Plath-Hughes one: meeting at Oxford, honeymooning in Venice, sharing a study, writing a book each, painting our North London living room French grey, babies in view. It broke down even so. During my divorce, I remember thinking: am I victim or beneficiary? Sylvia’s late poems suggest: always both. The speaker of ‘Lesbos’, ‘The Jailer’, ‘Daddy’ and ‘Lady Lazarus’ couldn’t be more of a victim, but she expresses herself as if no one has told her that. The Ariel voice makes something glorious of a woman’s always abject – divorced or not – position in the world. ‘Don’t talk to me about the world needing cheerful stuff!’ Sylvia wrote to her mother ten days after Ted left the marital home. ‘What the person out of Belsen – physical or psychological – wants is nobody saying the birdies still go tweet-tweet but the full knowledge that somebody else has been there & knows the worst, just what it is like.’ Another Sylvia emerges in late 1962, one that would no longer paint hearts and flowers on furniture: a badass nearly divorced Sylvia. It makes more sense of the odd junk-shop feel to Bonhams that day: a schoolgirlish green and navy tartan skirt had been put on a mannequin with a bright blue paisley 1960s top; a Victorian upholstered chair sat next to a glass and cane coffee table. But now it’s clear: the schoolgirl skirt and the Victorian chair belonged to her marriage, and the silken paisley and cane coffee table to her new life.

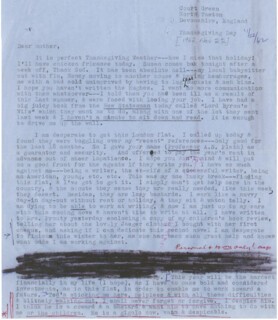

Sylvia considered some sort of open marriage, but felt she couldn’t stand it: ‘What I don’t want to be is an unfucked wife.’ Ted came back from London and told her ‘this is a prison, I am an institution, the children should never have been born.’ His attitude was like that of the hawk in his poems: ‘I kill where I please, it is all mine. He was furious I didn’t commit suicide, he said he was sure I would!’ She was scared she’d become a martyr like her mother; she hated the evenings and could only sleep with the help of pills, which wore off at 5 a.m. – her Devon midwife suggested she took her coffee then, and work on her writing until the babies woke up. Ted has ‘“got courage”’ and ‘deserted us’, she wrote home sarcastically to America. The lowest point came when she found Ted’s poems about Assia, ‘describing their orgasms, her ivory body, her smell, her beauty, saying in a world of beauties he married a hag, talking about “now I have hacked the octopus off my ring finger”. Many are fine poems.’ It was torture:

I am just frantic … I still love Ted … I am drowning, just gasping for air … I have no one … How can I tell the babies their father has left them … How and where, O God do I begin? … Frieda just lies wrapped in a blanket all day sucking her thumb. What can I do? I’m getting some kittens. I love you & need you.

At the end of this letter I was in tears, and had to stop reading. Plath received a reply from Beuscher before she posted the letter and added a postscript: ‘PS Much better. The divorce like a clean knife. I am ripe for it now. Thank you, thank you.’

The day Ted left, she wrote ‘The Applicant’: ‘Will you marry it?’ the salesman asks. ‘It is waterproof, shatterproof, proof/Against fire and bombs through the roof.’ The next day, she wrote ‘Daddy’: ‘I made a model of you,/A man in black with a Meinkampf look//And a love of the rack and the screw./And I said I do, I do.’ There is a recording from late 1962 of her reading both poems, her nasal Bostony accent sneering cheerfully through the dramatic monologues: they are almost camp, the way she tells them, and funnier than they have a right to be. ‘Right now I hate men,’ she wrote to her analyst. ‘I am stunned, bitter.’ And to her mother: ‘I am up at 5 writing the best poems of my life, they will make my name.’ (As if she didn’t already have a First Reading contract at the New Yorker, a novel in the press and a collection in the bookshops.) At around the same time, Ted wrote to his sister, Olwyn: ‘You’re right, she’ll have to grow up – it won’t do her any harm.’

In Devon, aged thirty with her husband gone, she rode horses and took up smoking. She learned how to keep the coal stove going all day – something Ted had never mastered. She did the paperwork, dug the garden, took the bins out. She had lost twenty pounds, but began cooking and eating again. ‘Ted may be a genius,’ she wrote to her mother, ‘but I’m an intelligence.’ She took up tarot, wondered about Connemara or Spain to escape another winter. Women rallied round her: after a telegram from Aurelia, her midwife found a 22-year-old trainee nurse to take care of the children while Sylvia wrote, late poppies and cornflowers on her desk. Ruth Fainlight wrote supportively from Tangier, accepting the dedication of ‘Elm’, and her family and friends in Massachusetts wrote and sent money and things for the children. But she refused to let her mother rescue her: ‘I must make a life as fast as I can,’ she wrote to her, ‘all my own.’ Prouty sent a cheque and suggested she go shopping. In Winkleigh, Sylvia went to the hairdresser, getting a more fashionable fringe cut in but keeping the long braid she curled around her crown. She went to Jaeger – ‘it is my shop’ she told Prouty – and bought a camel suit and sweater, a blue and black tweed skirt, a green cardigan, black sweater and red wool skirt, with earrings, hair clasp and bracelet made of pewter to match. ‘My new independence delights me.’ She planned to raise the hems of all her old clothes.

Around her birthday at the end of October, she made a trip to London – she had settled on moving back there, among friends, and found a flat on Fitzroy Road in Primrose Hill, where Yeats once lived. Alvarez had told her she was the first woman poet he’d ‘taken seriously since Emily Dickinson’, and she visited him and read him her new poems. She also intended to go to ‘a literary party to celebrate a poetry anthology I am in, & which Ted was one of the three editors of. He will probably be there, and with someone else, but I must get used to meeting him at these literary gatherings & braving it out, or I shall lose all sorts of professional opportunities,’ she told Prouty. She was working on ‘Lady Lazarus’. ‘O my enemy,’ Plath has Lazarus say, ‘Do I terrify?’ She is expensive, a ‘pure gold baby’:

There is a charge

For the eyeing of my scars, there is a charge

For the hearing of my heart –––

It really goes.And there is a charge, a very large charge

For a word or a touch

Or a bit of bloodOr a piece of my hair or my clothes.

So, so Herr Doktor.

So, Herr Enemy.

The Lazarene woman is a Jewish-survivor of the Nazi slaughter, a sinner-survivor of Lucifer’s fire, but mostly I like to think of Sylvia steeling herself against coming face to face with her rival, her ex and all the gossipers, with the drumbeat of these fuck-you lines in her head: ‘Out of the ash/I rise with my red hair/And I eat men like air.’

Soon she was back in London for good, furnishing Fitzroy Road: ‘I have fresh white walls in the lounge, pine bookcases, rush matting which looks very fine with my straw Hong Kong chairs & the little glasstopped table, also straw & black iron,’ she told Aurelia. (This is the one I saw at Bonhams.) ‘Now I am out of Ted’s shadow everybody tells me their life story & warms up to me & the babies right away. Life is such fun.’ She described the Ariel poems as being written in the ‘still, blue, almost eternal hour before cockcrow, before the baby’s cry, before the glassy music of the milkman’, and announced to her mother she was leaving the red of her previous life behind in favour of blue: ‘Blue is my new colour, royal, midnight (not aqua!) Ted never liked blue, & I am a really blue-period person now.’ Frieda was slowly emerging from the ‘awful regression she went into after Ted’s desertion’. Nick was not yet a year old. She began filing for divorce and accepted Ted’s offer of £1000 a year for them to live on, low though she thought it was. The Bell Jar came out, under a pseudonym, to acclaim. ‘Ted comes about once a week to see Frieda & sometimes is nice & sometimes awful,’ she wrote to her mother at the end of January. It was cold, there were power cuts and she was lonely. ‘The upheaval over, I am seeing the finality of it all … I shall simply have to fight it out on my own over here.’ The same day she wrote to Marty: ‘Everything has blown & bubbled & warped & split –– accentuated by the light & heat suddenly going off for hours at unannounced intervals, frozen pipes, people getting drinking water in buckets & such stuff –– that I am in a limbo between the old world & the very uncertain & rather grim new.’ (The next day, in ‘Balloons’, she wrote of a child biting into ‘travelling/Globes of thin air’ and being left with a ‘red/Shred in his little fist’.) Also on that day, Monday, 4 February 1963, she wrote to her analyst:

I feel a simple act of will would make the world steady & solidify. No one can save me but myself but I need help & my doctor is referring me to a woman psychiatrist. Living on my wits, my writing –– even partially, is very hard at this time, it is so subjective & dependent on objectivity. I am, for the first time since my marriage, relating to people without Ted, but my own lack of centre, of mature identity is a great torment. I am aware of a cowardice in myself, a wanting to give up. If I could study, read, enjoy people on my own Ted’s leaving would be hard, but manageable. But there is this damned, self-induced freeze. I am suddenly in agony, desperate, thinking Yes, let him take over the house, the children, let me just die & be done with it. How can I get out of this ghastly defeatist cycle & grow up. I am only too aware that love and a husband are impossibles to me at this time, I am incapable of being myself & loving myself.

Now the babies are crying, and I must take them out to tea.

With love,

Sylvia

A week later, on Monday 11 February, Plath was found dead in the kitchen at Fitzroy Road. She had left milk and bread for her children, sealed the kitchen door, placed her cheek on a cloth in the oven and turned on the gas. She was thought to have died between 4 and 6 a.m., the time of day when her sleeping pills wore off. ‘Edge’, written six days earlier, imagined a woman ‘perfected./Her dead//Body wears the smile of accomplishment.’ Ted Hughes, who was in bed with the poet Susan Alliston in the early morning of 11 February, maintained that he and Sylvia had been ‘days’ away from getting back together. ‘My love for her simply continues,’ he wrote to Aurelia in May 1963. The odd thing is that her last thoughts don’t really contradict his: they could be reunited, but she would still have to find her way out of her old identity and into a new one. ‘I suppose suffering is the source of my understanding,’ she wrote to Prouty, ‘and perhaps one day I shall be a better novelist because of this.’ And perhaps a different sort of wife, who didn’t think marriage was something she could only disappoint.

I sometimes like to imagine that Sylvia Plath didn’t die at all: she survived the winter of 1963 and she still lives in Fitzroy Road, having bought the whole building on the profits of The Bell Jar and Doubletake, her 1964 novel about ‘a wife whose husband turns out to be a deserter & philanderer although she had thought he was wonderful and perfect’. She wears a lot of Eileen Fisher and sits in an armchair at the edge of Faber parties, still wearing the double-dragoned necklace that was sold at auction earlier this year, with the badass divorcée pewter bracelet on her wrist like an amulet. She is baffled by but interested in MeToo. She still speaks Boston-nasally, but with rounded English vowels. She stopped writing novels years ago, and writes her poems slowly now she has the Pulitzer, and the Booker, and the Nobel. She is too grand to approach, but while she’s combing her white hair and you’re putting on your lipstick in the loos, you smile at her shyly in the mirror and she says: ‘What the the fuck are you looking at?’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.