There is a moment towards the end of King Lear – many readers and playgoers have found it almost unbearable – when the mad king enters, holding his daughter’s corpse in his arms. ‘Lend me a looking glass,’ Lear says, ‘If that her breath will mist or stain the stone,/Why then she lives.’ Two of his subjects respond, with questions that go on resonating down the centuries:

Kent: Is this the promised end?

Edgar: Or image of that horror?

Shakespeare’s first audience would have understood ‘the promised end’ to mean Doomsday – the end of the world – and ‘image’ to mean exact likeness. Edgar is asking if the scene of madness and murder in front of him is as close a rendering as he will ever be given, before the fact, of the Triumph of Death to come.

These are questions that viewers have often put, perhaps even with Kent’s and Edgar’s bewildered anguish, to Picasso’s Guernica; and the evidence suggests that they continue to be asked of the painting, in spite of the world’s enormous changes, by those three or four generations who have lived since the mural’s unveiling eighty years ago. For some reason – no doubt for many reasons, some of them accidental or external to the work itself – Picasso’s painting has become an essential, or anyway recurring, point of reference for human beings in fear for their lives. Guernica has become our culture’s Tragic Scene. And for once the phrase ‘our culture’ seems defensible – not just Western shorthand. There are photographs by the hundred of versions of Guernica – placards on sticks, elaborate facsimiles, tapestries, banners, burlesques, strip cartoons, wheat-paste posters, street puppet shows – being carried in anger or agony over the past thirty years in Ramallah, Oaxaca, Calgary, London, Kurdistan, Madrid, Cape Town, Belfast, Calcutta; outside US air bases, in marches against the Iraq invasion, in struggles of all kinds against state repression, as a rallying point for los Indignados, and – still, always, everywhere, indispensably – an answer to the lie of ‘collateral damage’.

But why? Why Guernica? How does the picture answer to our culture’s need for a new epitome of death – and life in the face of it? The questions are not rhetorical: it could, after all, have been otherwise. Guernica might have proved a failure, or a worthy but soon forgotten success. It was made by an artist who was well aware, the record shows, that in taking on the commission he was straying into territory – the public, the political, the large-scale, the heroic and compassionate – that very little in his previous work seemed to have prepared him for. When Josep Lluís Sert and other delegates of the Spanish Republic came in early 1937 to ask Picasso to do the mural, he told them he wasn’t certain that he could produce a picture of the kind they wanted. And he was right to have doubts. Was there anything in his previous art on which he could draw in order to speak publicly, grandly, to a scene of civil war? It is true that since the mid-1920s his painting had centred on fear and horror as recurrent facts of life. Violence, once he had tackled it head on in the Three Dancers of 1925, became a preoccupation. So did monstrosity, vengefulness, pitiful or resplendent deformity – life in extremis. But none of these things need have added up to, or even moved in the direction of, a tragic attitude. Treating them did not necessarily prepare an artist to confront the Tragic Scene: the moment in human existence, that is, when death and vulnerability are recognised as such by an individual or a group, but late; and the plunge into undefended mortality that follows excites not just horror in those who look on, but pity and terror.

In the ten years preceding Guernica Picasso had been, to put it baldly, the artist of monstrosity. His paintings had set forth a view of the human as constantly haunted, and maybe defined, by a monstrous, captivating otherness – most markedly, perhaps, in the Punch and Judy show of sex. ‘Au fond, il n’y a que l’amour,’ he said. This was as close, I reckon, as Picasso ever came to a philosophy of life, and by ‘love’ he certainly meant primarily the sexual kind, the carnal, the whole pantomime of desire. In his art monstrosity was capable of attaining to beauty, or monumentality, or a kind of strange pathos. But do any of these inflections lead to Guernica? Are not the monstrous and the tragic two separate things? To paint Guernica, in other words, wasn’t Picasso obliged to change key as an artist and sing a tune he’d never before tried; and more than that, to suppress in himself the fascination with horror that had shaped so much of his previous work? (The belonging together of ecstasy and antipathy, or fixation and bewilderment – elation, absurdity, self-loss, panic, disbelief – is basic to Picasso’s understanding of sex, and therefore of human life au fond. And the very word ‘fascination’ speaks to the normality of the intertwining: its Latin root, fascinus, means simply ‘erect penis’.) But isn’t Guernica great precisely to the extent that it manages, for once, to show us women (and animals) in pain and fear without eliciting that stunned, half-repelled, half-attracted ‘fascination’?

Many have thought so. But the story is more complicated. I doubt that an artist of Picasso’s sort ever raises his or her account of humanity to a higher power simply by purging, or repressing, what had been dangerous or horrible in an earlier vision. There must be a way from monstrosity to tragedy. The one must be capable of being folded into the other, lending it aspects of the previous vision’s power.

Aristotle, in the first account of tragedy to have come down to us, is already wondering about the difference between tragedy and monstrosity. ‘Tragedy,’ he says in a famous passage, ‘is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain grandeur; in language embellished with each kind of artistic ornament, the several kinds being found in separate parts of the play … producing pity and terror in the audience, and thereby cleansing the audience of these emotions.’ The word bequeathed to us by the last sentence is katharsis, whose roots seem to lie in medicine or rituals of purgation. Why the experience of pity and terror in the theatre is cathartic Aristotle never explains – he seems to take it as self-evident. Some have questioned Aristotle’s confidence, others (like Brecht) have disapproved of the cleansing. Is pity an emotion we want to be purged of? Are we right to call it an ‘emotion’ in the first place? But let me put these questions aside – they take us towards insoluble mysteries – and return to the question of the monstrous. Aristotle knows full well that horror and disproportion are intrinsic to tragedy’s appeal. But he makes a distinction between the appearance of the dreadful on stage and its unfolding in an action – its progress towards a moment of recognition. Tragedy, he admits, is partly a matter of theatrical effect: the circular stage, the dancing and wailing chorus, the backdrop of the ‘scene’. He calls this physicality ‘spectacle’ and is conscious of its power:

Pity and terror may be aroused by means of spectacle; but they may also result from the inner structure of the piece, which is the better way … For the plot ought to be so constructed that, even without the aid of the eye, he who hears the tale will thrill with horror and melt to pity at what is taking place … To produce this effect by mere spectacle is a less artistic method … Those who employ the means of spectacle end up creating a sense not of the Terrible but only the Monstrous, and are strangers to the true purpose of tragedy.

The terrible and the monstrous – these do seem repeated terms of Picasso’s art after 1925. And spectacle, as Aristotle understood it, is certainly Picasso’s god. But in Guernica didn’t he find a way to make appearance truly terrible, therefore pitiful and unforgivable – a permanent denunciation of any praxis, any set of human reasons, which aims or claims to make what actually happens (in war from the air) make sense?

Perhaps. Guernica’s users have often thought as much. But again, the question is how.

It might help to treat the two concepts involved in the idea of a great downfall becoming visible, comprehensible, even restorative, one by one. First, ‘scene,’ second, ‘tragic’ – that is, first the question of space and containment, and second that of terror and catharsis.

What marks Guernica off from most other murals of its giant size is the fact that it registers so powerfully as a single scene. Certainly it is patched together out of fragments, episodes, spotlit silhouettes. Part of its agony is disconnectedness – the isolation that terror is meant to enforce. But this disconnectedness is drawn together into a unity: Guernica does not unwind like a scroll or fold out like a strip cartoon (for all its nods to both idioms); it is not a procession of separate icons; it is a picture – a distinct shape of space – whose coherence is felt immediately by the viewer for all its strangeness.

‘Space’ is shorthand, I recognise. In the case of Guernica, what seems to matter most is the question of where the viewer is standing in the bombed city. Are we inside some kind of room? There are certainly walls, doors, windows, a table in the half-dark, even the dim lines of a ceiling. But doesn’t the horse opposite us look to be screaming in a street or courtyard, with a woman holding a lamp pushing her head through a window – a filmy curtain billowing over her forearm – to see what the noise is outside? Can we talk of an ‘outside’ and ‘inside’ at all in Guernica? Are the two kinds of space distinct? We seem to be looking up at a room’s high corners top left and right, but also, above the woman with the lamp, at the tiles on a roof. There is a door flapping on its hinges at the picture’s extreme right edge, but does it lead the way into safety or out to the void? How near to us are the animals and women? If they are close by, as appears likely, looming over us – so many giants – does that proximity ‘put us in touch’ with them? Does proximity mean intimacy? How does the picture’s black, white and grey monochrome affect our looking? Does it put back distance – detachment – into the scene, however near and enormous individual bodies may seem? Where is the ground in Guernica? Do we have a leg (or a tiled floor) to stand on? Literally we do – the grid of tiles is one of the last things Picasso put in as the picture came to a finish. But do any of the actors in the scene look to be supported by it? Does it offer viewers a foothold in the criss-cross of limbs?

The reader will have understood that the best answer to almost all of these questions is: ‘I’m not sure.’ And spatial uncertainty is one key to the picture’s power. It is Picasso’s way of responding to the new form of war, the new shape of suffering. Uncertainty about the nature of space is, further, a charged matter for him – especially when the space in question is that of a room, a table, walls, windows, a chequerboard floor. For the room is the form of the world for Picasso. His art depends on it. Guernica puts in question, that is, the very structure of Picasso’s apprehension.

This brings us back to the moment of Cubism. (It is important that Guernica deliberately invokes the ghost of that older style, with its monochrome colour and hard-edged geometry. The mural, we might say, shows us the Cubist world coming to an end.) The word ‘Cubist’ itself is of very little use: it seizes on a superficial aspect of Picasso and Braque’s reconstruction of seeing and tries to make it the essence of a style. But what drove Cubism forward between 1910 and 1914 was something larger than this: a new feeling for space as we moderns encounter it. And the pattern of feeling was twofold: it admitted and savoured as never before in art the strangeness, the fragmentation, of our 20th-century surroundings; but at the same time it demonstrated (and the style does have the precision and force of a demonstration) an absolute, naive confidence in a certain frame for those fragments, a special place in which the new strangeness and volatility could be given their head. That frame was the room. Or putting the matter more guardedly (since the room itself does not necessarily have to be figured in Picasso for its distinct form of spatiality to be invoked), the frame was ‘room-space’.

The world in Cubism – as is clear in the monumental still lifes from 1924 and 1925, where Picasso summed up his view of things – is laid before us as on a table. Behind the table is very often a wall, a window, the outline of a door, a high corner, panelling, wallpaper, floor tiles, a balcony rail. Having a world at all, for Picasso, seems to be premised on firm containment. Art is enclosure. Being is being in. Landscapes, he later told a friend, were foreign territory: ‘I never saw any … I’ve always lived inside myself. I have such interior landscapes that nature could never offer me ones as beautiful.’ The world in Picasso, putting it less grandly, is usually not far away, and most often smaller than us, or perhaps the same size. It can be grave – the dark Still Life from 1925 belonging to the Centre Pompidou has an ominous edge to it – but for the most part it is familiar and accommodating, full of instruments, toys, utensils, fruit, booze, newspaper, bits of sculpture, asking the viewer to touch. These things, and the space that contains them, are property. Picasso began his life as a bohemian, and lived during his first Cubist years in places where property was shabby and deteriorating: the wallpaper was old-fashioned, the armchair creaky, the upholstery a fright. There is still a little of this atmosphere in Guitar and Mandolin (1924). But it does not matter – rooms, interiors, furnishings, covers, curlicues are the ‘individual’ made flesh. No style besides Cubism has ever dwelt more deeply, more exultantly, in the space of possession and manipulation. The room was its model of beauty.

To a certain degree, then, even the idea of Cubism as geometry is defensible. One takes the measure of the dazzling, billowing tablecloth and amoeboid guitar in Guitar and Mandolin, for example, and soon comes to realise that the instabilities of particular things here are offset – steadied, balanced, locked into place – by the hard-ruled cube corners pinned to the picture edge. But the ‘cube’ is essentially the shape of a room – the shape of a kind of knowledge. Cubist ‘facets’ are the room’s sharp edges reiterated in the property it protects.

And yet … This sounds, in the end, too stable and reassuring. The first viewers of Picasso’s paintings were understandably divided between those who thought they saw in the pictures a special coolness and rationality (with maybe even a Kantian tinge) and those who warmed to, or panicked at, the pictures’ Nietzschean wildness. The room in Picasso is always a two-fold reality. It is the space of safety and pleasure – the guitar sounding, the bottle uncorked – but also a place of threat. ‘I believe in phantoms,’ he told his old friend, the art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, in 1944. ‘They’re not misty vapours, they’re something hard. When you want to stick a finger in them, they react.’ ‘I think that everything is unknown,’ he said to André Malraux, ‘everything’s the enemy! Everything! Not just some things! – women, babies, animals, tobacco, games … Everything!’

It is this combination of domesticity and paranoia – of trust in the room and deep fear of the forces the room may contain – that makes Picasso the artist of Guernica. He would have loathed and despised General Mola’s pronouncement of 19 July 1936:

We must spread terror. It is imperative to show that we are the ones in control, by eliminating unscrupulously and without hesitation all those who do not think as we do. There can be no cowardice. If we hesitate for a moment and fail to proceed with utter determination, we shall not win.

But he would have understood it. Terror and the wish to dominate were basic to Picasso’s worldview. All rooms – all human creations – are fragile shells. Enemies are lying in wait. The death-haunted drawings Picasso did in 1934 – rooms with lacerated bodies on a bed, bomber-swallows hurtling through a window, walls and rafters looking on murder – do no more than bring this fear to the surface. The Pompidou Still Life’s interior is already a tomb.

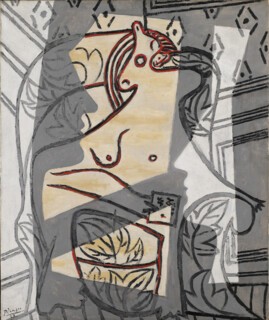

So perhaps I need to step back a little from my characterisation of Picasso as the artist of monstrosity. It could be that what arrives in 1925 with the Three Dancers is less monstrosity than existence transfigured by fear. Everything is unknown, and therefore hostile. In Woman in an Armchair (1927), for example, the naked figure is criss-crossed – pinioned – by what seem to be shafts of light from a window. They could just as easily be the glare of an incendiary. The yellow of the nude’s flesh seems about to catch fire. And then we see that the shadow and light have taken the form of two faces left and right – whose gender, unusually for Picasso, is indeterminate. Phantoms. That the two faces are not overtly menacing makes no difference. They are other; they should not be there; they disturb the logic of room-space. The woman in the armchair has every right to scream.

There is a fable of the origin of language told by Rousseau that I think Picasso would have liked: ‘A primitive man, on encountering other people, will have had as his first experience fear. That fear will have made him see those others as larger and stronger than himself; he will have given them the name giants.’ Commentators on Rousseau have pointed out that ‘giant’ is too weak, or at least too definite, a word for the fear – the unknown-ness – that the story tells us drives on the first act of naming. ‘Monster’ would be better. Rousseau continues:

After many further experiences, the man will discover that the supposed giants [monsters] are neither larger nor stronger than himself, and that their stature did not match the idea he had first attached to the word giant. So he will invent another name common to both them and himself, such as for example the word man, and will keep the word giant [monster] for the false object that struck him in his first delusion.

Picasso would have admired the fable because it recognises that alarm and misrecognition are at the very root of perception. Other people are monsters first, ‘men and women’ second. And always insecurely.

Three pieces of testimony to Picasso’s feelings about such matters are worth adducing – two comic, one tragic-comic. First, a memory of how the body appeared to him in infancy, as recounted to Roland Penrose:

Picasso once told me how, when very young, he used to crawl under the dinner table to look in awe at the monstrously swollen legs that appeared from under the skirts of one of his aunts. This childish fascination by elephantine proportions impresses him still.

And this, from Françoise Gilot:

When I was a child, says Picasso, I often had a dream that used to frighten me greatly. I dreamed that my legs and arms grew to an enormous size and then shrunk back just as much in the other direction. And all around me, in my dream, I saw other people going through the same transformations, getting huge or very tiny. I felt terribly anguished every time I dreamed about that.

Finally, a story told by Kahnweiler. One day in November 1933 (the year is important, and we know that events in Germany were monitored closely in Picasso’s circle) the artist came back from a meeting – or was it a session? – with Jacques Lacan. They had fallen out over a recent murder case. Earlier in the year two maids from Le Mans, the Papin sisters, had slaughtered their mistress and her daughter. They had gouged out their victims’ eyes, beaten them to death and then gone to bed, lying naked to await the arrival of the police. Kahnweiler reports as follows:

Picasso has seen Dr Lacan, with whom he is not at all in agreement: ‘He claims that the Papin sisters are mad,’ he said. And Picasso went on to declare that he admired the Papin sisters, who had dared to do what each of us would like to and nobody dares to. ‘What becomes of tragedy, then? Et les grands sentiments? La haine?’

I reminded him that the judges had not considered the sisters to be mad.

Picasso: ‘Yes, the judges, they have a classical education … Today’s psychiatrists are the enemies of tragedy, and of saintliness … And saying that the Papin sisters are mad means getting rid of that admirable thing called sin.’

These are hard sayings – the kind of thing Picasso’s biographers feast on. My task is to think of them as an aspect of the mind that went to make Guernica. Monstrosity of the Papin sort, Picasso seems to be asserting (and again I suggest that the wider tragedy of 1933 is in the background), is what the human reveals itself to be, for good or ill, at moments of maximum intensity. It is bound up with the claim to individual autonomy and impatience with the given order. The Christian notion of sin gets us close to it, as does the Greek hubris. The judges with their classical education are better equipped than the analyst to understand this: the word ‘tragedy’ comes twice to Picasso’s lips. ‘Drama’, likewise, is a term that recurs in his conversations, alongside hurt and hatred. Hatred is the other side of love, he believes, or maybe love is a mask that hatred wears – one of many. The world is hostile, we know that already. ‘I never appreciate, any more than I like. I love or I hate. When I love a woman, that tears everything apart – especially my painting.’

Some of this is play-acting and provocation; but the core ideas are deeply felt. Putting the dreadfulness of the Papin sisters’ violence into a separate category of the ‘mad’ means, as Picasso sees it, that we close ourselves against everything in the two women’s conduct – in the affect we imagine for them – that we know to be ordinary, indelible, dangerous in ourselves, and fundamental for the making of the ‘I’. The word he blurts out is ‘hatred’: meaning destructiveness, deep resentment of the Other and its power, a tearing and rending that lie at the heart of the self’s constitution. And other things too: guilt (‘sin’), plus its desperate, necessary, never-to-be-finished disavowal by the subject; and therefore – because guilt remains – the eternal appeal of the taboo, the ‘wicked’, the transgressive.

Guernica is a tragic scene – a downfall, a plunge into darkness – but distinctively a 20th-century one. Its subject is death from the air. ‘That death could fall from heaven on so many,’ Picasso told an interviewer later, ‘right in the middle of rushed life, has always had a great meaning for me.’ A great meaning, and a special kind of horror. The historian Marc Bloch had this to say in 1940:

The fact is that this dropping of bombs from the sky has a unique power of spreading terror … A man is always afraid of dying, but particularly so when to death is added the threat of complete physical disintegration. No doubt this is a peculiarly illogical manifestation of the instinct of self-preservation, but its roots are very deep in human nature.

Bombing of the kind experimented with in April 1937 – ‘carpet bombing’, ‘strategic bombing’ ‘total war’ – is terrifying. Because the people on the ground, cowering in their shelters, may imagine themselves suddenly gone from the world – ripped apart and scattered, vanished without trace. Because what will put an end to them so completely comes out of the blue – Picasso’s ‘from heaven’ – and has no imaginable form. Because death from now on is potentially (‘strategically’) all-engulfing: no longer a matter of individual extinctions recorded on a war memorial, but of whole cities – whole ‘worlds’, whole forms of life – snuffed out in an hour or so. The war diary of Wolfram von Richthofen, chief of staff of the German Condor Legion, speaks naively – with true totalitarian glee – to this moment of technical mastery:

Guernica, city of five thousand inhabitants, literally levelled. Attack was launched with 250kg bombs and firebombs, these about one third of the total. When the first Junkers arrived, there was already smoke everywhere (from the experimental bomber squadron, which attacked first with three planes). Nobody could see roads, bridges or suburban targets anymore, so they just dumped their bombs in the midst of it all. The 250s knocked down a number of houses and destroyed the municipal water system. The firebombs now had time to do their work. The type of construction of the houses – tile roofs, wooden floors, and half-timbered walls – facilitated their total destruction. Inhabitants were generally out of town because of a festival [not true]; most of those fled at the outset of the attack [ditto]. A small number died in wrecked shelters [numbers still disputed, but certainly not small]. Bomb craters in the streets are still to be seen. Absolutely fabulous!

To which the only possible reply (at least in words) is Picasso’s own, on Christmas Day 1939: a poem that turns and turns, obsessively, around the image of an eagle bomber vomiting its wings on houses below – skin ripped off the houses, flames on the buildings’ torn flesh, a window flapping against the void, horror discovered in the drawer of a wardrobe (always the dream of the room remaining), shutters broken, a black flag burning … The dramatis personae of Guernica, repeated as impotent spell:

le charbon plie les draps brodés de la cire des aigles

tombant en pluie de rires l’écheveau glacé des

flammes du ciel vide sur la peau

déchirée de la maison dans un coin au fond du tiroir de

l’armoire vomit ses ailesclaque à la fenêtre oubliée sur le vide

le drap noir déchiré du miel

glacé des flammes du ciel

sur la peau arrachée à la maison

dans un coin au fond du tiroir

l’aigle vomit ses ailessur la peau arrachée à la maison

claque à la fenêtre oubliée au centre du vide infini

le miel noir du drap déchiré par des flammes glacées

du ciel l’aigle vomit ses ailesau centre infini du vide sur la peau arrachée à la maison

claquent à la fenêtre les bras nus du miel du

drap noir déchiré par la glace des flammes du

ciel empuanté par l’aigle vomissant ses ailesa fenêtre oubliée au centre de la nuit secoue

le drap noir dévoré par la glace des flammes

l’aigle vomit ses ailes sur le miel du ciel

immobile au centre de l’espace

la peau arrachée à la maison

secoue le drap noir de sa fenêtre

l’aigle pris dans les glaces

vomit ses ailes dans le cielle drap noir de la fenêtre claque sur la joue du ciel

emporté par l’aigle vomissant ses ailes

arraché des dents du mur de la maison la

fenêtre secoue son

drap dans le charbon du bleu grillé aux lampes

les ongles des persiennes

abandonnent la lutte ses ailes à la chance

This dreadful parody of a sestina – the same few phrases patched to one another endlessly, as if in hope that a combination will occur in which suddenly the world will be made whole again – seems to me the closest Guernica ever comes to being provided with a running commentary.

Guernica – I go back to the question of tragedy – is above all a picture of women and animals looking for death: trying to ‘face’ annihilation, to see where it is coming from and what form it will take, so as to attain Aristotle’s moment of recognition (anagnorisis). And their tragedy is that they cannot find it. The woman with the lamp is the emblem of that condition, but her directedness – her right-to-left velocity, face and arm extruded through the slats on the window – is seconded by the woman stumbling and peering below, and the desperate backwards stare of the horse.

Picasso’s poem tries to mimic this looking and not seeing. Its absurd syntax and senseless enjambments end up making the individual images of bombing, which in themselves should be vivid and repellent (the eagle, the window, the black flag, the flames), flatten out into a mad patter of words. Something is happening in the poem: the poem is about not knowing what. Those who care for Guernica have always responded to just this aspect of the painting: its darkness and nowhere-ness, the desperate effort of the dying to see what is done to them, death as immediacy, discontinuity, ‘detonation.’

We could say that the nowhere-ness and isolation in Guernica are what terror – terror with von Richthofen’s technology at its disposal – most wants to produce. It is the desired state of mind lurking behind the war-room euphemisms: ‘undermining civilian morale’, ‘destroying social cohesion’, ‘strategic bombing’, ‘putting an end to war-willingness’. But surely Guernica would not have played the role it has for the past eighty years if all it showed was absolute negativity. It is a scene, after all, not a meaningless shambles. It presents us, at the degree zero of experience, with an image of horror shared – death as a condition (a promised end, a mystery) that opens a last space for the human.

This is hard to think about, and Hannah Arendt is helpful. In her book On Violence she ends by discussing Franz Fanon’s claim that armed struggle against an oppressor is to be welcomed as a great social equaliser, the destroyer of shame and subservience, and therefore (Fanon says) the road to freedom and solidarity. Arendt is unhappy with the proposal, but recognises its force:

Of all equalisers, death seems to be the most potent, at least in the few extraordinary situations where it is permitted to play a political role. Death, whether faced in actual dying or in the inner awareness of one’s own mortality, is perhaps the most anti-political experience there is. It signifies that we shall disappear from the world of appearances and leave the company of our fellow-men, which are the conditions of all politics. As far as human experience is concerned, death indicates an extreme of loneliness and impotence. But faced collectively and in action, death changes its countenance; now nothing seems more likely to intensify our vitality than its proximity. Something we are usually hardly aware of, namely, that our own death is accompanied by the potential immortality of the group we belong to and, in the final analysis, of the species, moves into the centre of our experience. It is as though life itself, the immortal life of the species, nourished, as it were, by the sempiternal dying of its individual members, is ‘surging upward’, actualised in the practice of violence.

By ‘practice’, in the final sentence, Arendt seems to mean something close to Aristotle’s idea of Action, which is to say activity with a purpose and direction; practice accompanied, however dreadful the circumstances, by an effort at recognition and appropriation, making catastrophe ‘ours’. Guernica is action in this tragic sense: its central trio of heads – the horse, the woman with the lamp, the woman below ‘surging upward’ – is stopped for ever in a moment of charged vitality. They cannot see, they must see. No figures have ever been more isolated, no scene has ever declared itself more a totality (a human thing) made from the fragments.

Arendt is understandably reluctant to accept Fanon’s conception of politics. She goes on to argue that no real polity, no continuing community, can be built on the foundations of fraternity engendered by collective violence – even by men and women forgetting their differences in the face of imminent death – because ‘no human relationship is more transitory than this kind of brotherhood, which can be actualised only under conditions of immediate danger to life and limb.’ But I would counter that Guernica, in depicting this transitoriness, has succeeded in perpetuating it – in immortalising it, to use Arendt’s terms – and goes on presenting us with a usable model of the ‘potential immortality of the group’. That the group is shattered and panic-stricken, reassembled by nothing but the extremity of terror, only speaks to the form collectivity now takes. Guernica’s users have understood this ever since 1937, to the discomfort of governments: ‘community’, as we have it, is this life in the moment of the bomb.

It is difficult, maybe impossible, to describe what is happening here without one’s language tipping into the falsely redemptive. Nothing that takes place in Guernica, to make my own feeling clear, strikes me as redeemed or even transfigured by the picture’s black-and-white reassembly of its parts. Fear, pain, sudden death, disorientation, screaming immediacy, disbelief, the suffering of animals – none of these realities ‘falls into place’. Judith Butler in a recent essay, looking for a basis on which a future politics might be built, asks her readers to consider the idea of a collectivity founded on weakness. ‘Vulnerability, affiliation and collective resistance’: these, she argues, are such a commonality’s building blocks. I believe that Guernica’s usefulness – its continuing life in so many different contexts – may derive from the fact that it pictures politics in much the same way. We should remember that in the early stages of work on the canvas Picasso saw armed struggle differently, even with a little of Fanon’s heroics: the bombing was centred for a while on a beautiful dying nude male, fist clenched, reaching skyward, asserting the ‘immortality of the group’. But then the fist evaporated and the hero became a broken statue. The image of politics Guernica ended up proposing was one in which ‘affiliation’ and ‘collective resistance’ are there in human ‘vulnerability’, if the latter can be shown – understood – as a shared tragic fate.

Arendt rightly invokes Georges Sorel’s Reflections on Violence at this point: Sorel is her anti-Fanon. Insofar as a new political identity can be thought of as being forged through violence, Sorel says, it will not come from armed struggle pursued as a project – a ‘continuation of politics by other means’ – but from violence experienced as, pictured as, pity and terror. Socialism, Sorel believed – ‘socialism’ was his term for that ‘vulnerability, affiliation and collective resistance’ Butler aims to bring into focus – is nothing if not a ‘picture of complete catastrophe’. His other words were ‘obscurity’ and ‘mystery’ – which bring us again to the idea of tragedy. ‘Socialism has always inspired terror because of the enormous element of the unknown which it contains.’ And the unknown is socialism’s strength. Any politics that truly intends to break out of the vicious circle of ‘progress’, Sorel thought – today’s phrase would be ‘economic development’ – has to recognise that ‘the war undertaken by socialism against modern society’ involves looking havoc full in the face.

Reflections on Violence has very often been anathematised for saying as much; and it is true that aspects of Sorel’s thought in the book were eventually pulled into the orbit of fascism. But I see no necessity in this. Sorel’s compassion for the defenceless shines through on every page; his contempt for defenders of the guillotine is boundless. And his picture of catastrophe and community still provides us with the frame we need to interpret Guernica’s politics.

No doubt many people will dispute the idea that Guernica is the best image we have of ‘modern society’ – of the 20th century and its legacy. But it should strike us again – we tend to take it for granted, and we shouldn’t – that the painting has, through generations, assumed this role for so many. ‘We seem to have before us’, as A.C. Bradley said of the Greeks,

a type of the mystery of the whole world, the tragic fact which extends far beyond the limits of tragedy. Everywhere, from the crushed rocks beneath our feet to the soul of man, we see power, intelligence, life and glory, which astound us and seem to call for our worship. And everywhere we see them perishing, devouring one another and destroying themselves, often with dreadful pain, as though they came into being for no other end.

Bradley, in his late Victorian way, sees the facts of destruction and waste he points to – the perversion of ‘power, intelligence, life and glory’ – as mysteries, permanencies of the human condition. I leave that argument aside. I am interested instead in what has emerged as new – as newly intolerable and exacerbated – in our own societies’ confrontation with armed conflict, and the way this newness connects with Guernica.

Could we say that the special agony of modernity has turned out to be that it goes on being lived in a state of permanent contradiction – between the ongoing pacification of everyday life that is modernity’s great achievement and the ever increasing visibility of war that accompanies it? I put my stress here on the idea of visibility. We are circling back to Aristotle’s notion of ‘spectacle’, which extends to all things appealing primarily to the faculty of vision: the Greek word is opsis. Modernity is a system of incessant opsis. So the prominence of war in modernity – and the fear that it may be modernity’s truth – is not a matter of more and more (or less and less) actual conflict, but of violence as the form – the tempo, the figure, the fascinus – of our culture’s production of appearances.

Why violence ‘appeals’ to the eye in this way may be one of Bradley’s (and Sorel’s) insoluble mysteries. But certain commonsense things can be said about the changes in warfare over the past half-century. War is no longer a segregated, professional, mercenary ‘continuation of politics by other means’. It is an everywhere haunting the happiness of consumerism. It has become what military theorists call asymmetrical: that is, less and less a matter of ‘legitimate’, concentrated armed forces squaring off in the ring of roughly equal states, but rather of violence escaping, diffusing, metastasising, becoming the business of ‘non-state actors’. Ressentiment sits in its joyless apartment, twisting the wires on the circuit board. The white van is heading our way.

Perhaps, then – though the thought is a grim one – we turn to Guernica with a kind of nostalgia. Suffering and horror were once this large. They were dreadful, but they had a tragic dimension. The bomb made history. Mola and von Richthofen were monsters in the labyrinth. ‘And everywhere we see them perishing, devouring one another and destroying themselves.’ It may be true, in other words, that we pin our hopes on Guernica. We go on hungering for the epic in it, because we recoil from the alternative – violence as the price paid for a broken sociality, violence as leading nowhere, violence as ‘collateral damage’, violence as spectacle, violence as eternal return. But how could we not recoil? And does not the image Guernica presents remain our last best hope? For ‘vulnerability, affiliation and collective resistance’ still seem, to some of us, realities worth fighting for.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.