The Lee Krasner retrospective at the Barbican (until 1 September) is not to be missed. It is rare these days to be given a chance to assess the seriousness and beauty of the best Abstract Expressionist painting. The style is unfashionable: it is thought to be overwrought, supersized, ‘American’ in a 1950s way (‘great again’) and heavy with male cigarette smoke. Krasner had her opinions about all these charges, which are far from empty: the small room containing four paintings she did in 1956 – Prophecy, Birth, Embrace, Three in Two – is about as frightening a pictorial space as can be imagined. Its vision of glamour and nudity and sex is ghastly, which doesn’t mean the paintings lack powder-puff appeal. Pin-up grins have never been closer to screams of pain.

The Prophecy pictures were made in tragic circumstances. By 1956 Krasner’s marriage to Jackson Pollock was all but broken. In August that year, while Krasner was in Europe, Pollock’s Oldsmobile came off the road at speed, killing himself and Edith Metzger, a friend of his lover, Ruth Kligman. Kligman survived the crash. The paintings Krasner made in response to the horror – and this is almost always her strength – are deeply engaged with other people’s imagery. Fighting with De Kooning’s Woman, as she does throughout – fighting and feeding on his colour, the scale and shape of his Cubist body parts, his bad faith fascination with Marilyn Monroe gorgeousness (bad faith because his irony is so obviously an alibi for gloating) – is her way of discovering what ‘woman’, that terrifying abstraction, meant for her. Out of the engagement comes the originality. Dripping paint, for example, was already a tired Ab Ex trademark by 1956, by no means De Kooning’s exclusive property. But no one had made dripped paint so unlovely, so impatient and passionless, as Krasner did the pinks and whites in Birth. (The tone of the title is undecidable.) For the fight with De Kooning to end in victory, other painters’ weaponry had to be taken out of the closet, some of it distinctly old-fashioned. Krasner was never up to date. Three in Two, for example, evokes explicitly, and not just in its title, the savage Jungian splitting and swapping of genders that Pollock had gone in for a decade earlier, during the time of Two and Male and Female. Behind those paintings lay Picasso, specifically Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Krasner was monstrously confident that she could mobilise this big machinery without in the least repeating its moves – or rather, that she could use the moves to deliver an entirely new, and dreadful, sense of closeness and inhumanity. Embrace, for example, is Les Demoiselles churned into viscera.

The room with the 1956 paintings is not typical of the Barbican show as a whole. Krasner’s mood is wonderfully variable, and her revelling in the power of her own pictorial intelligence very often a joy, or at least a consolation. It is crucially wrong to paint her as victim, but callous to brush aside what must have been constant unhappiness: living with Pollock was enduring genius and lunacy day in day out. I’m sure she would have snorted at my ‘lunacy’ diagnosis, and said – as she did say more than once – that experiencing the genius almost made up for the booze, the self-harm, the harm to others. What she seemed to care about most in life was painting. She knew what hers gained from looking at Pollock’s and resisting.

The space at the Barbican is curious, and can be deadening, but on this occasion it has been put to use in just the right way. The gallery is arranged on two levels. On the ground floor, where one enters, there is a cluster of open galleries in a kind of atrium lit from above, where the large abstract paintings Krasner did in the early 1960s are hung. They are magnificent. I found it hard to drag myself away from them and get a sense of what was happening in the smaller side rooms, and then to go upstairs, through a sequence of spaces showing mainly paintings and drawings from the 1940s and 1950s. But eventually I did, and the shape of Krasner’s career began to emerge. The two-floor arrangement round the atrium means that a viewer can come out from any one of the rooms upstairs and look straight down at the big abstractions, with the kinds of earlier artistic discipline that fed this final freedom freshly in mind. The discipline had centrally to do with Cubism: it was because she was just as far inside the skin of Picasso and late Braque and early Gorky as De Kooning was that she could turn his means against him. Just before the terrible year of Embrace and Prophecy she is at her coolest and most delicately balanced: Cubist shards floating in blue or pale green ether; titles like Milkweed and Blue Level speaking to the mood – the naturalism. There is no lack of anguish in 1955 – the off-key crimsons and oranges of Desert Moon and Bird Talk are bloodthirsty (profoundly original), and the pinks already sneering at De Kooning’s Woman V or VI – but even in Bird Talk, where the coloured pieces look ready to cut anyone daring to touch, the final Cubist precision of placement turns cacophony into call and response.

There is an enormous amount to look at in the Barbican show. The loans are generous – great things from America, but also from Melbourne, Valencia, Bern – the choice of works unerring, the wall texts and catalogue helpful throughout. Recently I heard someone who had written intensely about Krasner some years ago say that the show had helped her finally untie a difficult knot: the way anger for Krasner – and who cannot feel it? – had kept company, unconsciously, with anger at her. Why had she borne it – the pain, the ‘wife of the artist’ label, the condescension – so long? Because painting was worth almost anything, she felt; because a good painting was pure delight; and because she believed her painting was on its way to greatness. Neither the first nor the last of these opinions is likely to endear her to a contemporary art audience, but they were her essence.

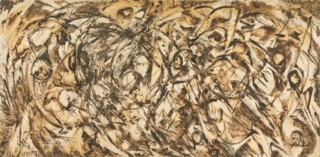

There seems to have been a lull for four years following 1956. It’s not hard to imagine why. Then paintings came with a rush: large paintings – The Eye Is the First Circle measures around eight by sixteen feet – and beautifully judged mid-scale accompaniments. Triple Goddess, for example, is roughly seven feet high and five feet wide. Truly large scale in abstraction is a trap. Bombast threatens. Kinds of handling or pictorial rhythm that Krasner had made her own in paintings the size of Milkweed, say, which has essentially the same measurements as Triple Goddess, could easily start to look like mannerisms when magnified by two. They might not register as issuing from a specific kind of whole-body movement that came into being, and dictated its own speed, as the work went on. The painting could look constructed, not made.

None of this happens in 1960. Krasner did not paint large, or preserve the large paintings she did (she was always a ruthless destroyer of work she thought second-rate), until she knew she had in her a movement with the brush that needed vast emptiness as a starting point. Immediately in 1960 there is a consistency of mark in her abstractions wholly unlike any other painter’s. The shape of each touch is distinctive, as well as its implied pace and the strangely gentle pressure of the brush – gentle to the point of weakness, but a weakness entirely controlled, deliberate. Even when the marks on canvas are relatively sparse – not as sparse as Franz Kline’s, it’s true, but much less emphatic, less locally bold, with primed canvas predominating – what is characteristic about the space Krasner creates is that it is stuffed full, close to us, full of feathers, kapok, soft flurries and pillows of light-coloured stuff. It is entirely unlike the space she had seen Pollock invent for modern painting, his tangled, ethereal Sea Change infinities, criss-crossed by Comet and Shooting Star. No wonder she struggled to find titles for the proximity she’d discovered. I’m not sure about Polar Stampede. Assault on the Solar Plexus ditto. Happy Lady, by contrast, is exquisite pictorial comedy with title to match.

I was dreading finding the big 1960s paintings overblown – ‘big statements’. Bad reproductions and worse recollections of canvases like Polar Stampede littered my mind. The real things are entirely different. At the Barbican the light, and the consideration given to the spacing and grouping in each half-open room, helps immensely. It’s the unexpected softness that goes with the showmanship which escapes reproduction: the softness of so many of the marks and the way they cradle and cosset the overall whites and pale brown washes of the canvas, pressing the whole fabric of paint gently forwards. The softness isn’t the kind that calls up the word ‘feminine’. Part of Krasner’s point (forgive me for making her paintings seem like arguments when they are pure discovery, whatever answering-back they contain emerging from the task at hand) is to have softness and hardness coexist in abstract art, and to prize away vehemence of touch from assertion or confession or any sort of reach-me-down heroics. Maybe she hoped that demonstrating her own way of having gentleness and decisiveness float free of each other would encourage people to look again at Pollock’s version of unassertiveness, which she went on thinking painting must come to terms with. No such luck.

There are many other great things in the Barbican show, and inevitably some failures. Ab Ex was a hit or miss business. Krasner’s advantage was her certainty about her strength and her allegiance to Cubism – her persistence in thinking it the true modern style. The big 1960s abstractions are Cubism reinvented. Polar Stampede would be better called Sorgues in the Snow.

A room near the beginning of the show is hung with six astonishing life drawings Krasner did in 1940, aged 32, while at Hans Hofmann’s School of Fine Arts in New York. The two most abstract drawings in the sequence are ferociously sure of their Cubist means. The nude body in each concedes to (or maybe divulges) an up-front geometry, done in thick bold line. The claim seems to be that the diagram registers the pose’s internal stresses. I for one am convinced. Hofmann rightly gets hammered these days for the form of his praise of these drawings – he said something like ‘they’re so good they don’t look to have been done by a woman’ – but at least he knew this was Cubism fully fledged. Krasner got her own back on her teacher (whom she revered) and on her own true-believer young self when, much later, she came across some old Hofmann School drawings in her studio and cut them up to make big cantankerous collages, half-laughing at the old ‘push and pull’ religion. These canvases too are at the Barbican. They may not be Krasner at her best, but they are deeply touching; and their mixture of ferocity and nostalgia, homage to Cubism and impatience at any attempt to turn the style into a ‘method’, led throughout her life to the beauty she treasured.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.