Time has a way of turning radicals into authorities. Thomas Aquinas was provocative during his lifetime because he sought to ground Christian theology in Aristotelian philosophy. Marx was exiled, Socrates poisoned. Moses Maimonides, known in the Jewish tradition by the honorific ‘Rambam’ (for Rabbi Moses ben Maimon, his real name), was celebrated centuries after his death as a towering figure in both philosophy and law, but in his own day was a controversial figure. The Provençal rabbi Abraham ben David (‘Rabad’) criticised him for, among other things, his insistence that God is not embodied. After his death in 1204, Jews living in Montpellier helped persuade the Christian authorities to burn copies of his greatest philosophical work, The Guide to the Perplexed. Rabbis at Acre condemned him in 1288.

The tension that gave rise to these misgivings is at the heart of The Guide to the Perplexed. The work is addressed to Maimonides’s student Joseph Ibn Shimon, and by extension to anyone troubled by the same issue as Joseph – that is, the apparent conflict between Aristotelian science and Jewish religion. Aristotle’s God is an immaterial intellect, which gives rise to eternal celestial motion simply by thinking about itself. The God of the Torah, by contrast, is an emotional and wilful being, who created the world in a known span of time. This God seems to have a body, because he ‘sits’ and ‘stands’. He apparently has spatial location, since he is said to dwell ‘high in the heavens’ and then to ‘come near’. He is even compared to such tangible earthly phenomena as fire and rock.

Jewish intellectual traditions had sometimes embraced this kind of language. The Shiur Qomah, or Measure of the Body, a collection of sayings supposedly revealed to Rabbi Ishmael, claimed to calculate the enormous size of God’s body parts (‘between the sole of his foot and his ankle is a thousand myriads and five hundred parasangs’). Maimonides dismissed it as a forgery. For him, indulging in any corporeal description of God was unacceptable, because it could be proven through the laws of eternal motion that God has no body. This created a problem for those who wished to read scripture literally. How could the word of God conflict with what had been proved to be true?

Maimonides and Joseph weren’t the only scholars asking that question. In an Islamic context, the relationship between revelation and reason was being interrogated by another Andalusian philosopher, Ibn Rushd, known as Averroes. Maimonides and Ibn Rushd had a good deal in common. Both were experts on the legal traditions of their respective religions. Both were steeped in Aristotelian philosophy and took inspiration from earlier scholars who wrote about philosophy in Arabic, especially al-Fārābī, whose works Maimonides called ‘finer than fine flour’. They even came from the same town: Córdoba, in Islamic Spain, though Maimonides left when he was young, after the persecution of the Jewish population by the Almohads. He eventually settled in Cairo, where he wrote The Guide to the Perplexed and the Mishneh Torah, a systematisation of Jewish law that was responsible for his reputation as a religious scholar among subsequent generations of Jews (it was known as ‘the mighty hand’, an allusion to the end of the Book of Deuteronomy, which refers to the great deeds of Moses).

Ibn Rushd had adopted a rationalist position when considering the potential clash between reason and revelation. He argued in a legal ruling that philosophers alone can determine which interpretations of the Quran are viable: after all, the Quran is true and, as Aristotle said, ‘truth cannot contradict truth.’ Starting from first principles, the philosopher can establish further conclusions that borrow their certainty from those principles. As an Aristotelian, Ibn Rushd assumed that the Quran’s meaning must align with Aristotle’s teachings. This is far from evident at first glance, but only because, he argued, Muhammad’s revelation was intended for ordinary people, who cannot appreciate or follow demonstrative arguments.

For Maimonides, the problem was more complicated. He, too, thought that scripture was aimed at a wide audience of believers and required careful interpretation. He would also have agreed that these interpretations cannot contradict proven philosophical truth – hence his insistence on God’s incorporeality and transcendence. But he was less optimistic than Ibn Rushd about the prospect of settling matters by means of rational argument. A particularly contentious example was the creation of the universe. Three ideas had been proposed as to how God had accomplished it. According to Aristotle and his followers (including Ibn Rushd), the universe is eternal. It has always existed and will always exist. For Plato, the universe is not eternal, but was created at a fixed point in time. As God made it out of something, however, there must have been pre-existing matter, like wood waiting to be turned into tables and chairs. Then there was the position adopted by most Jews, that God created the universe in time and from nothing.

In The Guide to the Perplexed, Maimonides claims that there is no way to determine which of these three positions is correct. This might seem to cast doubt on Aristotle, but Maimonides points to a passing comment in a treatise on argument theory in which Aristotle says that eternity is a difficult matter and open to disputation. Seizing on that remark, Maimonides argues that Aristotle, too, must have realised that the issue cannot be settled by reason. In this, he was followed by Aquinas, whose Summa Theologiae cites the same Aristotelian passage to the same effect. Aquinas also adopted Maimonides’s overall solution to the problem of eternity (if we can call it a solution). Maimonides seems to find the Platonic idea of eternally pre-existing matter unattractive, but declares the contest between Aristotelian eternalism and biblical creationism a draw as far as rational argument goes. Jews can believe in creationism, he thinks, because it seems the more straightforward way to understand scripture. And in addition, a temporal creation goes well with the idea that God freely chose to make the universe, instead of producing it through some sort of automatic process.

It’s a nuanced and perhaps unstable position, which advises belief as the consequence of agnosticism. Maimonides seems to be saying that if you would like to believe something you may do so, so long as you first verify that there is no compelling, rational argument to the contrary. And creationism was something Maimonides wished to believe. He calls it the ‘indispensable basis of the whole religious Law’, presumably because a God who chooses to create might also choose a people as his own and issue commandments that apply only to them. Some philosophers of religion recommend a similar policy today. We might not be able to prove the existence of God, but it is still rational to accept it by faith if we have removed all ‘defeaters’ to theism. For example, the theist has to rebut the argument that the presence of evil in the world is inconsistent with the existence of a benevolent and omnipotent deity. It can be rational to believe without absolute proof, but it can never be rational simply to ignore arguments showing that your beliefs are false.

If this approach is Maimonidean in spirit, it’s not one that he adopted on this question. God’s existence could be proved, he thought, regardless of what we conclude about the eternity of the universe. If the universe isn’t eternal, then God must exist, because God is the cause of its coming into being. If the universe is eternal, things are a bit more complicated. A large part of The Guide to the Perplexed is devoted to showing how an Aristotelian eternalist would demonstrate God’s existence, along with 25 other principles needed to make the argument coherent.

Though this even-handed procedure is most commonly associated with Maimonides, a Muslim contemporary, Ibn Ṭufayl, was making the same argument: that God’s existence can be proven whether we assume eternalism or creationism. Ibn Ṭufayl was an associate of Ibn Rushd and the author of a remarkable narrative called Ḥayy Ibn Yaqẓān, whose eponymous hero grows up on a remote island and works out the fundamentals of philosophy through independent reflection. Ḥayy realises that he can prove the universe has a creator even if it did not begin at a fixed moment in time:

Since matter in every body demands a form, as it exists through its form and can have no reality apart from it, and since forms can be brought into being only by this Creator, all being, Ḥayy saw, is plainly dependent on him for existence itself … Thus he is the Cause of all things, and all are his effects, whether they came to be out of nothing or had no beginning in time and were in no way successors to non-being.

For philosophers devoted to the authority of Aristotle but nervous about the clash between his cosmology and the creationism of the Abrahamic faiths, it was reassuring to think that God’s existence could be established either way. A modest rationalism was a natural response in the face of criticism aimed at the pretensions of Aristotelian science. Religious philosophers insisted on the limits of reason while demanding that it stay in its proper lane. Thus Maimonides is confident about the claims of natural philosophy when it comes to things on earth, but far more tentative when it comes to the heavens. The motions and make-up of the stars have never been explained scientifically, he says, and on this topic Aristotle himself was indulging in ‘intuition and conjecture’. ‘With matters beyond human ken,’ he argues, ‘to tax one’s mind with thoughts beyond us, things we have no way of knowing, is senseless, even delusional.’

This ‘epistemic humility’, as the historian Daniel Frank calls it, is also on show in The Guide to the Perplexed’s discussion of divine attributes. At first this section may seem bold in its embrace of the deliverances of philosophy; Maimonides explicitly rejects the apparent meaning of many scriptural passages that describe God as embodied, something reason deems inadmissible. In fact, though, his negative approach to theological discourse is a corrective to our tendency to suppose we understand the transcendent. Any comparison, however implicit, between God and created things must be rejected. This means that we can’t talk about God in himself at all. There are two caveats to the rule, both inspired by ideas that reached Maimonides from the Islamic theological tradition. First, we can talk about what God does, the acts he performs in the world. This is permitted because what we are really talking about is effects in the world, rather than God. Second, Maimonides allows us to speak of God in negative terms, for instance by saying that he is not a body, not in place, not sitting, not standing and so on.

Why, then, does the Torah contain positive descriptions of God? To answer this question, Maimonides deploys his formidable interpretative skills, using scripture to undermine superficial readings of scripture. Both Isaiah 40:18 (‘To whom wilt thou liken God?’) and Jeremiah 10:6 (‘None is like thee, Lord’) serve as guidelines against the kinds of remark he rejects. He also offers many examples of scriptural passages where language is used figuratively. A reference to a time ‘before the hills were born’ (Psalms 90:2) doesn’t mean that the hills had parents. Similarly, there is scope to say that God’s having a ‘place’ refers to his transcendent rank or degree, and that his ‘sitting on a throne’ refers to his majesty and sublimity, not an actual chair.

An obvious problem with this approach is that it seems to preclude any knowledge of God, or indeed, any possibility of saying things about him that are true. This could be a first step along the path of the mystics, who revelled in an experience of God that transcended language and rational thought. Maimonides did have some influence on the Jewish tradition of Kabbalah, but he was no mystic. Instead, he argued that we can learn a lot about something by issuing denials about it. His example was a ship. You can be told that it is not a mineral, animal or plant; not an accidental property of another thing; not flat, but not spherical or solid either. Maimonides claims that by the end of this process one would have a concept of a ship not unlike that of someone with a positive understanding. More plausibly, he says that it is at least some advance to learn that God is not a body, not a soul, not affected by any cause and so on: ‘The more you can prove inapplicable to God, the better; and the more you affirm of him, the more you anthropomorphise and the further you stray from real knowledge of him.’

I take this wording and some of the translations above from the new translation of The Guide to the Perplexed by Lenn Goodman, a historian of philosophy, and Phillip Lieberman, a historian of law; this is the right combination of expertise for tackling Maimonides. Another specialist in philosophy, Shlomo Pines, published an edition in 1963 prefaced by an influential, and to some notorious, essay by Leo Strauss, which argued (to oversimplify) that what The Guide to the Perplexed doesn’t say is more important than what it does say.* There is also a translation by Michael Friedländer from 1881. What distinguishes the new version is its attempt to capture what Goodman and Lieberman call Maimonides’s ‘intimate, conversational tone’, which they privilege above literal accuracy. Cross-checking their version against the Arabic, one routinely finds that some words are rendered paraphrastically or not at all. (Like most Jewish medieval philosophical works, The Guide to the Perplexed is written in Judeo-Arabic, that is, Arabic in Hebrew script.) The more technical side of Maimonides’s writing often vanishes in the English, though the ample footnotes make up for this to some extent. In literal translation, the sentence I quoted in the previous paragraph ends ‘the more you distance yourself from an understanding of his true nature’ (ʿan maʿrifa ḥaqīqatihi), ‘true nature’ (ḥaqīqa) being a piece of Arabic philosophical terminology equivalent to ‘essence’.

But what this version lacks in fidelity to the Arabic it makes up for in readability. The tone is not just conversational, but entertainingly abrupt and at times even sarcastic. I suspect the translators used a thesaurus to come up with the wide range of terms of abuse their Maimonides applies to his opponents, which include ‘numbskull’, ‘ignoramus’ and ‘slackers’. His transitional remarks are well served by Goodman and Lieberman’s colloquial English, as here: ‘My own approach, in a nutshell: I say that either the world is eternal or it began.’ Here ‘in a nutshell’ stands for a long phrase in the Arabic that would slow things down. Having several very different options in English is no bad thing, and is perhaps fitting for a philosopher who was not afraid, on occasion, to tell his reader: ‘Choose the view you please.’

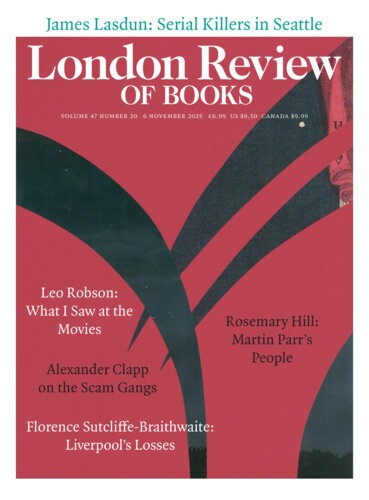

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.