‘Ithink we’ll get five,’ President Trump said, and five was what he got. At his prompting, the Republican-dominated Texas legislature remapped the districts to be used in next year’s elections to the federal House of Representatives. Their map includes five new seats that are likely to be won by the Republicans, who already hold 25 of the state’s 38 seats. Until this year, the Democrat Al Green’s Ninth Congressional District covered Democrat-leaning south and south-western Houston. Now, it ranges east over Republican-leaning Harris County and Liberty County, with most of the former constituency reallocated to other districts. Green has accused Trump and his allies in Texas of infusing ‘racism into Texas redistricting’ by targeting Black representatives like him and diluting the Black vote. ‘I did not take race into consideration when drawing this map,’ Phil King, the state senator responsible for the redistricting legislation, claimed. ‘I drew it based on what would better perform for Republican candidates.’ His colleague Todd Hunter, who introduced the redistricting bill, agreed. ‘The underlying goal of this plan is straightforward: improve Republican political performance.’

King and Hunter can say these things because there is no judicial remedy for designing a redistricting map that sews up the outcome of a congressional election. In 2019, Chief Justice John Roberts declared that although the Supreme Court ‘does not condone excessive partisan gerrymandering’, any court-mandated intervention in district maps would inevitably look partisan and impugn the court’s neutrality. In 2017, during arguments in a different case, Roberts contrasted the ‘sociological gobbledygook’ of political science on gerrymandering with the formal and objective science of American constitutional law.

‘Sociological gobbledygook’ teaches that the drawing of the boundaries of single-member districts can all but determine the outcome of an election. Imagine a state with twenty blue and thirty red voters that must be sliced into five districts. A map that tracked the overall distribution of votes would have two blue and three red districts. But if you can put six red voters and four blue voters in each of the five boxes, you will end up with five relatively safe red districts. This is known as ‘cracking’ the blue electorate. Or you could create two districts with six blues and one with eight blues, making three safe blue districts by ‘packing’ red supporters – concentrating them in a smaller number of districts. The notion that democratic elections are supposed to allow voters to make a real choice between candidates, or even kick out the bums in power, sits uneasily with the combination of untrammelled redistricting power and predictable political preferences that characterise the US today. But if it is so easy for mapmakers to vitiate the democratic purpose of elections in single-member districts, doesn’t neutrality demand some constraint on the ability of incumbents to choose voters, rather than the other way round?

After the Texas redistricting, Roberts’s belief that neutrality requires inaction appears even shakier. By adding five seats to the expected Texan Republican delegation, the Republican Party improves the odds it will retain, or even increase, its six-seat majority in the House in November 2026. Even a slight advantage gained through redistricting may have national implications because the Democrats’ lead in the polls is consistently small (around two points). Congressional maps are usually redrawn once every ten years, after each decennial census (the next one is in 2030). Mid-cycle redistricting does sometimes happen – Texas did the same thing two decades ago – but it is unusual. So is Trump’s open embrace of gerrymanders. In 1891, Benjamin Harrison condemned gerrymandering as ‘political robbery’. Sixty years later, Harry Truman called for federal legislation to end its use; a bill was introduced in the House but died in the Senate. In 1987, Ronald Reagan told a meeting of Republican governors that gerrymanders were ‘corrupt’.

In August, before the Texas map was passed into law, most of the Democratic members of the state legislature left Austin, depriving it of a quorum. For two weeks, they took the waters in Chicago. In the end, they returned, tails between their legs, cowed by a fine of $500 a day for being absent without permission from the special legislative session and by the arrest warrants issued by the Texas governor, Greg Abbott. Other Republican-dominated states are following Texas’s example. Missouri’s Republican governor, Mike Kehoe, signed legislation in September creating a new map that will probably add one seat to his party’s caucus in Washington (Missouri is currently represented by six Republicans and two Democrats). Like Green in Houston, the targeted Democrat is a Black politician. Emanuel Cleaver was the first Black mayor of Kansas City and has spent twenty years in Congress. The new map slices up his district. It places the main hall of the Independence Boulevard Christian Church in Kansas City in one district, its parking lot in a second and the grocery store across the street in a third. It carves up Kansas City along the Troost Divide: Troost Avenue is a long north-south street that for decades marked the de facto border between white and Black areas of the city. Cleaver hopes to collect enough signatures to trigger a state-wide referendum challenging the redistricting.

Democratic states have threatened to retaliate. In California, Governor Gavin Newsom has scheduled a special election on Proposition 50, which would temporarily suspend the state’s independent redistricting commission, making it possible for the Democratic legislature to flip five Republican seats (43 of California’s 52 seats are held by Democrats). Like California, New York has a bipartisan commission, which usually redraws its maps once a decade. The Democrats have brought in legislation allowing mid-decade changes, but new maps won’t be in place until 2028. Democrats who used to be fierce advocates of independent commissions are now asking themselves whether they’ve been too slow to fight back. From a party that has a habit of bringing a knife to a gunfight, the question answers itself.

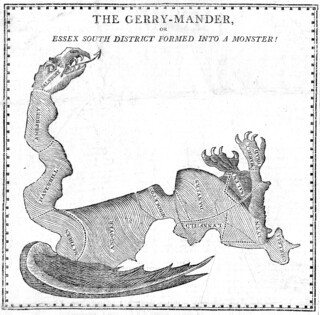

Democrats can’t excuse their political ineptitude by claiming that partisan redistricting is new. The term gerrymandering was coined after just such a scandal. In February 1812, the governor of Massachusetts, Elbridge Gerry, signed into law a map that heavily favoured Jefferson and Madison’s Republican Party. After seeing the strangely shaped new district running up the west and north sides of Essex County, breaking up a Federalist stronghold, the painter Gilbert Stuart is said to have exclaimed: ‘That will do for a salamander!’ ‘Better say a Gerrymander,’ Benjamin Russell, the editor of the Boston Centinel, replied. Another account attributes the neologism to the cartoonist Elkanah Tisdale, who supposedly entertained guests at a dinner party hosted by the Boston merchant Israel Thorndike by adding wings and claws to the new district. A cartoon showing the ‘Gerry-Mander’ was published in the Boston Gazette in March 1812.

In 1878, the House Speaker, Samuel Randall, a Pennsylvania Democrat, wrote to the party leadership in Ohio stressing that it was of the ‘utmost importance to the Democratic Party that the Ohio legislature should redistrict the state’. Between 1878 and 1886, Ohio engaged in five rounds of redistricting, with new maps being used for every congressional election held during those years. Ohio’s ‘dose of gerrymandering’ triggered bitter public recrimination. In 1890 the New York Times complained that there had been ‘more changes in the map of Ohio than have occurred in African geography in recent years’. Ohio wasn’t alone. In every year of the same period at least one state redrew its map. In Alabama, the Democratic majority packed every single ‘Black Belt’ county – where Black majorities were likely to vote Republican – into a single district, the Old Fourth. Congress was unwilling to do anything about such behaviour. The Apportionment Acts that followed every census sometimes required that states maintain equal-population districts, but this was often ignored.

New maps were not the only way of ensuring a particular result on election day. When the 1920 census revealed how decisively the United States had shifted from a rural to a majority-urban population – the fruit of Gilded Age industrialisation, the Great Migration and European immigration – rural representatives tried to argue that its results were misleading. Because the census had been held in January, they said, it had seriously undercounted the farm population. Census workers couldn’t reach many snowed-in farms, and seasonal workers were in the cities. Homer Hoch, a Republican from Kansas, produced a table showing that the number of unnaturalised aliens in the cities had supposedly further skewed the results. As a result of this campaign, Congress failed to alter the allocation of House seats as it usually did in response to the census.

States reacted to demographic change with what one scholar, Alexander Bickel, called ‘an orgy of inactivity’. For the first sixty years of the 20th century, Arkansas, Louisiana, Kansas, North Carolina, Maryland and Iowa made only minimal changes to their electoral maps, although their populations had shifted dramatically from rural to urban. By 1960, the most populous district in Texas had four times the number of inhabitants as the least populous one. In Tennessee, House legislative districts had between 3454 and 36,031 inhabitants. All of this suggests, once again, that when Chief Justice Roberts equated deliberate inaction with neutrality, he was wide of the mark.

In 1964, in Reynolds v. Sims, a Supreme Court stacked with postwar liberals struck down these unevenly populated districts as a violation of constitutional equality. The ‘one person, one vote’ principle protected against malapportionment, but didn’t stop gerrymanders. The most important provision of the Voting Rights Act, wrenched through Congress in 1965, required jurisdictions with a history of anti-Black discrimination to seek permission from a federal body before changing their election laws. Section 2 of the Act prevented states from adopting redistricting that served to dilute the voting strength of racial minorities, including Blacks, Hispanics, Asian Americans, Native Americans and Alaskans.

In the late 20th century, there were only ten seats nationally that repeatedly changed hands as a result of partisan gerrymandering, with control of the House flipping on just one occasion, in 1954. But in 2012, Republicans started to change this. Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Virginia were all sliced up. The increase in gerrymanders was in part a result of Redmap, the Redistricting Majority Project, a Republican initiative set up in 2010 which invested in the races for the state legislatures, such as Texas’s, tasked with drawing district maps. In 1981, Democrats controlled the mapmaking process in 164 seats, while Republicans controlled it in 50. By 2021, the Republicans controlled line-drawing for 187 seats, the Democrats 49. At the same time, computers had made it cheaper and easier to design maps optimising one party’s performance without breaking the legal constraints on redistricting, such as the Voting Rights Act and the prohibition on districts drawn on the basis of race. In the 1980s, it cost $75,000 to buy software to do this; by the early 2000s, programs such as Maptitude for Redistricting cost $3000.

Just as in the late 19th century, urbanisation is now producing new political geography: migration from Democrat-leaning states such as California, New York, Pennsylvania and Illinois means they will lose House seats after the 2030 census. Meanwhile, Texas, Florida, Georgia and North Carolina, all of which lean Republican, are set to gain seats. Texas’s gerrymander, in other words, foreshadows a change in national political power that is coming anyway.

There is also the possibility of more sudden change. In August, the Supreme Court indicated that it would hear a new round of arguments in a case concerning the legality of a majority-Black district in Louisiana ordered by a lower court as a remedy for a violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The congressional map passed by the state legislature in 2022 had included only one Black-majority district although almost a third of the state’s population is Black. The Supreme Court justices flagged an interest in a broader question: did the intentional creation of a majority-Black district violate either the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause or the 15th Amendment’s rule against racial barriers to voting? Depending on the way this question is framed and resolved, it could invalidate Section 2, or render it toothless. Because the pre-clearance provision of the Voting Rights Act (which blocks racially regressive election rules) has already been hobbled by a 2013 decision of the court, that would mean the end of legislated limits to states’ ability to dilute minority voting power. One immediate effect of invalidating Section 2 would be that the dozens of congressional districts long thought to be required by the Voting Rights Act could suddenly be gerrymandered out of existence and the opportunity for partisan gerrymanders would correspondingly expand.

Population change, gerrymandering and the judicial evisceration of protections for minority voters are all in play here, but it is difficult to make projections because these processes are unfolding at different rates. It’s hard to predict whether Californians will vote to redistrict, or whether Section 2 will survive. Still, there is little doubt as to the general direction of travel. Those who believe that the second Trump presidency has worked a sea change in American politics ain’t seen nothing yet.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.