Almost twenty years have passed since Amanda Knox, an American exchange student in Perugia, was arrested for the murder of her British housemate, Meredith Kercher, and it is nearly impossible, at this far remove, to convey the chaos that engulfed her. The lead prosecutor, Giuliano Mignini, pursued a case based on circumstantial evidence, gut instinct and his fantasies of female depravity, painting the 20-year-old Knox as a sex-crazed psychopath. His team leaked information about the investigation to the press, which published wild theories as fact (sample headlines: ‘ORGY OF DEATH’; ‘KNOX WAS A DRUGGED-UP TART’). Knox became a tabloid fixture, ‘Foxy Knoxy’. She and her boyfriend of one week, an Italian student called Raffaele Sollecito, were both found guilty in 2009; she was sentenced to 26 years in prison. (Knox and Sollecito were found to have acted with Rudy Guede, who in 2008 had been convicted of sexually assaulting Kercher and conspiracy to murder; he completed his sentence in 2021.) When, in 2011, DNA evidence exonerated Knox and Sollecito and they were acquitted on appeal, it was just as much of a shock to her as her initial conviction had been. Her new memoir chronicles her attempt to adjust to life after prison – or, as she puts it, ‘how I failed to reclaim my old life’, and what she gained instead.

But first Free takes us inside Capanne, the women’s prison near Perugia where Knox was incarcerated for almost four years. Her cell had a ‘steel bed frame painted pumpkin orange, a green foam mattress and a coarse wool blanket’. The doors were ‘unlike any I had ever seen: they were solid sheets of metal with no handles, just a hole where the handle should be.’ When prisoners were sent books the covers and spines had to be torn off, ‘leaving a wiggly bundle of pages swimming inside its dust jacket’. The rules were nonsensical: ‘Though we were allowed to have a camp stove that produced an open flame, we couldn’t have nutmeg – presumably because a woman on the cellblock had tried to snort it. We could clean with bleach, but we were forced to wear socks on our hands when it got cold, because we weren’t allowed to wear gloves.’ The ‘occasional rehabilitation programmes’ on offer included ‘theoretical beekeeping’. ‘Seriously, beekeeping without the bees?’

Knox was banned from common areas for the duration of the investigation. The only outdoor space she could access was a small courtyard next to the prison chapel. ‘Even when it was pouring rain, I circled that courtyard like a dog at a fence line, feeling the blood pump through my body, calming me.’ She improved her Italian by reading a translation of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire; Viktor Frankl’s memoir of his confinement in Nazi concentration camps, Man’s Search for Meaning, served as her ‘How to Survive Prison’ manual. She sang, at the top of her lungs, every song she knew by heart: the Beatles, Christmas carols, ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’.

Once she was moved to ‘general population’, Knox met Alessia, ‘who worked in the commissary’ and was ‘the black-market FedEx’ for notes, cigarettes and CDs, and Wilma, ‘who worked in the kitchen and had access to coveted garlic cloves, and who, if you were lucky, would clip you a sprig from the rosemary bush’. The Nigerian inmates nicknamed Knox ‘America’ and set up a table for her in the evenings: ‘One by one, I’d translate their court documents and letters from their boyfriends, and write out their innuendo-filled responses, translating the pidgin English … into proper Italian.’ From her fellow inmates, Knox learned Italian rap lyrics and how to make a prison cappuccino by shaking boiling milk in an empty two-litre water bottle until it foamed.

It wasn’t all dance parties and rolling pizza dough with a broom handle. She was sexually harassed by the prison comandante, cornered and grabbed by a guard. A paranoid cellmate ripped her journal to shreds. After her conviction, she was put on suicide watch:

We all knew the methods. One inmate in my cellblock had broken a plastic pen into shards and tried to swallow them. I heard about a guy in the men’s wing who had used his cooking stove and a plastic bag to asphyxiate himself. You could hang yourself with a bedsheet. I even thought that if I threw myself at the bed frame in just the right way, I could hit my head hard enough to bludgeon myself to death.

Knox’s divorced parents remortgaged their homes to pay for her legal defence; her mother, Edda, was on a plane to Italy even as Knox was being interrogated by the police. Knox’s friend Madison moved to Perugia in 2010 and visited her twice a week. Madison studied the research on false confessions, got a job as a photographer for the local paper and ‘in her spare time, she and an interpreter friend talked to journalists, lawyers and people on the street about my case.’ The Italian professor who had taught Knox at the University of Washington arranged for her ‘to keep earning credit through independent study’. A local politician and his colleague ‘brought me as many books as I could devour by my favourite Italian authors’. An expatriate couple from Seattle opened up their house near Perugia; Knox’s stepfather moved in for the final year of her imprisonment.

Her ‘best friend’ in prison was Don Saulo Scarabattoli, the Catholic chaplain. His gentle manner – knocking before entering her cell, crying during Kung Fu Panda – endeared him to her, as did his rumpled appearance: ‘Compared to the crisp lines and perfectly plucked eyebrows of so many of the cops and prison officials, his relaxed style felt almost … Pacific Northwest.’ Although Knox was an atheist, he invited her to play guitar during mass. The chapel had wooden pews and natural light, a view (through bars) of a small garden: the inmates ‘would sing along, happy to be there. The atmosphere was even festive at times. It was a warm, inviting and contemplative oasis.’ After her conviction, the conversations with Scarabattoli became more ‘philosophical’. They debated ‘gay marriage, adoption, the role of women in religious doctrine, vegetarianism, life after death. We disagreed, amicably, about many things.’ On what turned out to be her last day at Capanne, Scarabattoli gave Knox ‘a small, silver flying dove on a thin chain’ to represent the Holy Spirit and freedom. He told her he loved her ‘like a grandfather’ and recorded her singing a song by Cat Power.

After her release, a sympathetic ex-FBI agent helped Knox and her family get out of Perugia, ‘paparazzi ramming my stepdad’s car from behind’. At a safe house in Rome, she stayed up until dawn, afraid to go to sleep in case she woke up back in her cell. Arriving home in Seattle, Knox found her ‘childhood bedroom strewn with petals’: her friends had bought everything in the flower shop. ‘It was a beautiful gesture, like a scene out of a rom-com, but it also served to highlight how unfamiliar that room had become.’ Her mother’s house was besieged by news crews; she ‘drew every curtain in the house, and she hasn’t opened them since.’ Knox was claustrophobic, overwhelmed by the sheer amount of ‘stuff’ she owned. She filled bin bags with her old toy animals, Pokémon cards and manga.

She found relief in the landscape. Foraging for chanterelles with her Italian professor, ‘the spongy bed of pine needles on the forest floor, after years of standing on nothing but concrete, felt like it might spring me into the air. I was an astronaut bounding on the moon.’ Her senses were heightened, her curiosity ‘blazing’. When she and Madison moved into a cheap apartment, the keys ‘felt weighty and huge in my hand, like they could open the gates of a city’. She purged her wardrobe, replacing her ‘court and prison outfits’ with colourful clothes. At Arundel, her favourite second-hand bookshop, ‘I put my nose in the books, I caressed their spines, I bought as many as I could carry at a time.’ Hypervigilant, insomniac, she walked and cycled alone for hours, wandering ‘aimlessly’: ‘I was taking in the sights, both large and small, as if everything – a skyscraper, a ladybug on a rhododendron leaf – carried the same cosmic weight. I felt like a drifting ghost, unattached and insignificant.’ Visits to a trauma specialist and a silent meditation retreat triggered panic attacks. Knox was painfully aware of the sacrifices her family had made in their ‘one, all-consuming mission: save Amanda.’ To pay them back, at least financially, she wrote a memoir, Waiting to Be Heard. In March 2013, a month before publication, Italy’s Court of Cassation overturned her acquittal and ordered a retrial.

The TV interviews Knox gave while promoting her first memoir are difficult to watch. At that point, her innocence could still be questioned in public. Diane Sawyer of ABC interrogated her for seven ‘gruelling’ hours to produce a ten-minute segment. CNN’s Chris Cuomo, who clearly wanted to have it both ways, to ask gotcha questions and also be the good guy, warned her ahead of time that he was going to be ‘tough’, then asked: ‘Were you into deviant sex?’ ‘To this day,’ Knox writes, ‘I regret not choosing Oprah.’

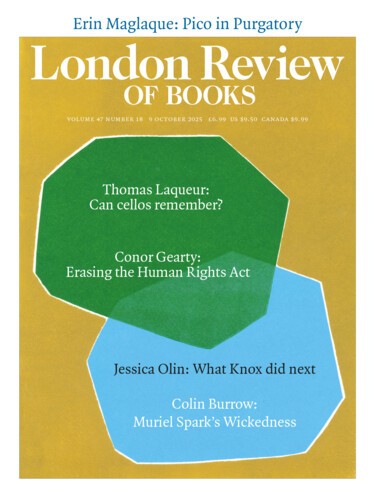

Waiting to Be Heard covers Knox’s first weeks in Perugia; her brief friendship with Kercher and her romance with Sollecito; the days leading up to Kercher’s murder; her brutal interrogation; her confession, in which she implicated Patrick Lumumba, the Black owner of the bar where she worked; the two years she spent in prison before trial; her conviction, appeal and eventual acquittal. Before the book’s publication, the press questioned the value of Knox writing about her own experience. In the New Yorker, Mark Singer dutifully explained why she had been acquitted but warned that ‘if she now elects to exploit and cash in on her celebrity, it will prove that she hasn’t learned much worth emulating.’ On the LRB blog, Lidija Haas predicted that ‘few will want to read’ the book.

Writers employed arch language – the killing was described as the result of a ‘sex escapade’ and ‘high jinks’ – and framed events as though they were fictional. The playwright John Guare, who called Knox ‘my kind of murderess’, wondered whether she was a heroine in the mould of ‘Daisy Miller, an innocent young girl who goes to Europe for experience? Or is she Louise Brooks, the woman who takes what she wants and destroys everything? Or is she Nancy Drew caught up in Kafka?’ Nathaniel Rich wrote in Rolling Stone: ‘One might expect that the lead role in this blockbuster would be assigned to the victim,’ but ‘the show was stolen by an accidental ingénue.’ Later, reviewing Waiting to Be Heard in the New York Review of Books, Rich admitted that he was ‘disappointed’: it turned out that ‘the story of two college students imprisoned for a crime they didn’t commit was far more complicated, and less dramatic, than the prosecution’s theory.’ (Two out of five stars.) Tom Dibblee’s review in the Los Angeles Review of Books picked at the scab of Knox’s ‘slight offness’, which ‘cuts through logic and taps a more primal lobe of the brain’. Of the book’s cover, he wrote:

I can barely make eye contact with Knox’s photo on the cover of her memoir. Her expression comes across as a transparent plea for sympathy, one that looks like feigned pain to mask indignation, feigned girlhood to mask sexuality, even feigned pain to mask true pain. After four years of prison and international pillory, I have no doubt that Knox has suffered. But the photo feels somehow unbearably false.

In the New York Times, Sam Tanenhaus was dismissive of Knox’s ‘well-orchestrated round of TV appearances’ and pointed out that her ghostwriter had previously collaborated with Socks, ‘the Clintons’ “first cat”’. Then he got on to what really bothered him: Knox’s sexual agency. Here Tanenhaus’s outrage dovetailed with the prosecution’s lurid fantasies: ‘Her candid summaries of flings and one-night stands exude triumphalism.’ (Wrong. In Waiting to Be Heard, Knox is ambivalent about each of her three – count ’em – hook-ups in Italy before she met Sollecito). Knox was ‘the aggressor in more than one instance’, he claimed, and ‘her conquest of the inexperienced Sollecito’ was ‘hasty’. Tanenhaus even had a go at Kercher, who ‘at the time she was killed was steamily involved with a rock guitarist’ – he was a student – ‘who lived in the apartment downstairs’.

Waiting to Be Heard was a bestseller. It caught the attention of an editor at the West Seattle Herald, who asked Knox if she’d like to write about the arts. She was initially suspicious of his motives, but agreed when he suggested she use a pseudonym. She got a second job behind the till at Arundel. But in January 2014 the Court of Cassation found Knox and Sollecito guilty for a second time. Faced with the threat of extradition and a 28-year prison sentence, Knox once again considered suicide. Meanwhile, her family plotted to smuggle her to safety. ‘At dinner, someone would drop a hint. “We know someone who knows someone. They have a basement … It’s well stocked. Enough for a short-term stay. From there, you would cross into Canada on a boat.”’

In April that year, Knox’s mother was contacted by the forensic DNA expert Greg Hampikian, director of the Idaho Innocence Project, who had called for Knox’s release. He invited them both to a conference in Portland, Oregon. Knox was ‘frankly terrified’ at the prospect: outside the main ballroom, ‘I stared down at the gaudy carpet. I was sweating through my shirt and shaking so badly I had to clench my teeth.’ (One of Knox’s strengths as a writer is the way she conveys the physical manifestations of trauma.) She was instantly embraced by her ‘new family’ of exonerees, mostly Black and brown men, older than her, who had been in prison far longer than she had, and who told her that ‘if a tame little white girl from the suburbs’ could be wrongly convicted, ‘maybe people would finally start paying attention.’ She began speaking publicly about her experience, criss-crossing the country ‘to tell my story, raise awareness, and help fundraise’ for local innocence projects. She had a new purpose. Then, in March 2015, she and Sollecito were definitively acquitted by the Court of Cassation.

Knox’s writing for the West Seattle Herald expanded from arts coverage to no longer pseudonymous essays under the headline ‘Amanda’s View’. She wrote about the damaging effects of celebrity culture and social media, her family, her PTSD, Don Saulo Scarabattoli. In ‘Mourning Meredith’, which is reproduced almost verbatim in Free, she remembered the ‘beautiful, banal moments we shared in the weeks we lived side-by-side … sunbathing on the terrace, her reading a mystery novel while I practised “Hey Ya” on the guitar’, the vintage clothing shop where Kercher found a sparkly silver dress to wear on New Year’s Eve. Most of the comments from readers were supportive, but Knox could still provoke violent reactions: ‘What a load of crap … You are alive and Meredith is dead … You are a vile person obsessed with you and only you. You are clearly a sociopath. You got away with murder so just shut up and go away.’

Knox wrote for other publications about legal cases that had become cultural flashpoints: ‘Michelle Carter Deserves Sympathy and Help, Not Prison’ (LA Times); ‘America Asked the Wrong Questions about Brittney Griner’ (Time); ‘Ghislaine Maxwell, Elizabeth Holmes and Me’ (Free Press). She sympathised with both Johnny Depp and Amber Heard over the way they were being tried in the court of public opinion. She also wrote well-researched and convincing pieces about defendants most people hadn’t heard of, including Melissa Lucio and Melissa Calusinski, both of whom admitted to killing young children after long police interrogations using tactics that have been shown to produce false confessions. (More recently, she wrote an article for the Atlantic, entitled ‘What Is Evil?’, about Bryan Kohberger, who killed four students at the University of Idaho in 2022.) Knox developed a series with Vice and Facebook Watch, The Scarlet Letter Reports, in which she interviewed other members of what she calls ‘the Sisterhood of Ill Repute’. She hosted a podcast, The Truth about True Crime, in which she tackled the genre’s exploitation of people’s ‘worst moments’ for entertainment. Monica Lewinsky, a fellow survivor of the crucible, became a ‘big sister’ to her. She was finding her feet.

A Netflix documentary released in 2016 did much to shift public opinion. The filmmakers interviewed not just Knox but also Sollecito, Mignini and Nick Pisa, a jaunty scandal-hound who had written many of the most scurrilous stories about the case and sold them to the Daily Mail. (Far from being remorseful, Pisa seemed delighted to recall those heady days.) The film was deliberately unsensational, and carefully went through the DNA evidence that ruled out Knox and Sollecito’s involvement in Kercher’s murder. It also gave Knox a new perspective on Mignini: hearing him speak, she understood that he had genuinely believed he was doing the right thing in prosecuting her.

She had fallen in love. Christopher Robinson was the first person she met after prison who saw her as ‘just Amanda’. He cooked her elaborate meals; she introduced him to her favourite books. They made co-ordinated costumes for Halloween parties and the historical re-enactment Renaissance Faire. (‘Don’t invite me to your Victorian era murder mystery party,’ she wrote on Instagram, ‘because I WILL show up dressed to … you know.’) ‘From the very beginning of our relationship, Chris and I played. For his birthday, I put together a cyberpunk live-action role-play scavenger hunt. For my birthday, Chris constructed an American Gladiator-style obstacle course at our local park.’ She was ‘rediscovering a part of my life that I was told, both explicitly and implicitly, was forbidden: joy’. They got married on ‘leap day’, 29 February 2020, just before the world shut down. Guests received a copy of The Cardio Tesseract, a book of the love poems Knox and Robinson had written for each other during their courtship. In one of them, Knox paid tribute to a rapper persona Robinson had jokily crafted:

Had I the dopest Cuban link chains,

iced out with diamonds and lemonade gold,

not some hollowed-out dookie rope chains,

I’m talking five solid kilos of gold,

I would hang those chains round your neck.

But being rich in not much else but love,

let me wrap my arms around your neck,

and I will be the pendant of your love.

The wedding was ‘a one-night interactive theatre piece for two hundred people, a romantic live-action episode of Doctor Who’. Knox gave birth to a daughter, Eureka Muse, the following year, and a son, Echo, two years later.

In 2019 the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Knox’s rights had been violated when she was first detained in 2007. Her statement following her interrogation ‘had been taken in a context of heightened psychological pressure’ and she hadn’t been given access to a lawyer. The Italian state was ordered to pay €18,400 in damages, costs and expenses. A few months later, the Italy Innocence Project invited Knox to come to its first ever justice conference and speak about ‘trial by media’. It is here that Free comes into its own. As a child, Knox had written letters to her mother whenever she needed to apologise or fix a situation. While at Capanne, she wrote an apology to Lumumba. (In 2024 she was given a three-year sentence for slandering him, but avoided jail since she had already served almost four years.) She wrote to the Kerchers, expressing her condolences and her own sorrow at Meredith’s death, and wrote to them again after her release. Now, before her return to Italy, Knox decided to write to the man ‘whose actions had derailed my life, irrevocably warped my image in the world’s eye, and invited the demon of despair into my life’, Giuliano Mignini.

After hearing her speech at the justice conference, Mignini responded to Knox’s letter, using the informal ‘tu’, as she had. He found ‘common ground with me over our shared trauma from the media. His character and actions had been distorted by the press, too.’ They corresponded throughout the Covid pandemic, their letters full of ‘the low-stakes and banal yet very real stuff of actual friendships’. Knox repeatedly pressed Mignini on whether he now recognised that she was innocent, and told him she wanted to meet face to face. He blamed the police for her ordeal, claiming that ‘had he been present during my initial interrogation, perhaps things would not have turned out as they did.’ He was adamant that ‘he had done nothing wrong, had never acted with hostility towards me and was merely doing his job.’ And yet ‘he told me that he often looked at photos from the trial, and a few in particular where the two of us were in the same frame. He noted my pained expressions.’ This once ‘nightmarish figure’ may have ‘taken on the role of some kindly, distant uncle’, but his letters unsettled her. After she had a miscarriage (unbeknownst to him), he ‘said something that made my skin prickle’: ‘Excuse me if I say so, but I know I can speak openly with you. Have you ever thought about becoming a mother? It would be wonderful to know that there is a little “Amanda” in the world besides the one so dear to me.’

The book’s most fascinating chapter recounts Knox’s experience of watching Una vita in gioco (A Life on the Line), an Italian TV adaptation of a Simenon novel. Mignini had suggested she watch it to ‘find the torment of the investigator after the end of a trial, a torment that he felt about me’. Inspector Maigret becomes convinced that despite his ‘meticulous’ investigation, he has arrested and convicted the wrong man, Heurtin, for a double homicide. He is plagued with doubt and even conspires with a judge to let the condemned man escape, until he discovers the true killer and Heurtin can be freed. Knox was ‘shocked’: ‘Was this Mignini’s indirect and veiled attempt at acknowledging his mistakes?’

Knox learned from another letter that Mignini had grown up across the street from a women’s prison: ‘As a child, he could see from his living room into the courtyard where the female inmates were allowed yard time.’ His father, who worked ‘on behalf of prisoners’, died when Mignini was four, and his mother became so friendly with the female prisoners that Mignini ‘grew up celebrating his birthday with the inmates’ children’. The ever logical Knox struggled to make sense of this new information: ‘I had not expected him to have such a deep connection with the humanity of the incarcerated,’ she writes. ‘I could only conclude that this meant that, however wrong he was, he really, truly believed, as he was prosecuting me, that I was a dangerous person who belongs in prison.’

Their faccia a faccia meeting finally took place in 2022. Scarabattoli mediated while Robinson and Eureka waited in the next room and Edda hyperventilated outside on a bench, convinced that it was all a trap and Knox would be arrested again on trumped-up charges. Mignini was ‘as tall as I remembered, but less imposing’. Once again, Knox declared her innocence. ‘I had nothing to do with Meredith’s murder,’ she told him. ‘You were wrong about me.’ And again, Mignini defended his actions, shifting the blame to others: ‘By the time I arrived, all I could do as a prosecutor was pursue the case against you.’ There were moments of ‘sharp disagreement’, and Knox never got her apology, but she still ‘felt triumphant’: Mignini was ‘so clearly moved by my presence and by this shared experience I had created for the two of us’. There are closing scenes in Perugia: Sollecito makes a wistful cameo; Knox stands outside Capanne and Via della Pergola 7, the house where it all went wrong.

In the absence of a religious framework like Mignini’s Catholicism, Knox, a ‘committed sceptic who held rationality as a prime virtue’, has sought wisdom from various sources: Jung, Marcus Aurelius, Seneca, a Werner Erhard-influenced life coach, Japanese and Indian religious and cultural traditions. She told Interview magazine that Zen Buddhism was ‘my jam’; in Free she tries to make sense of her experience by drawing on the concepts of kintsugi and ikigai. This white-girl cobbling together isn’t as cringeworthy as it first seems. Knox’s fascination with Japan goes back to her adolescence: she applied off her own back to Seattle Prep because it was the only local school where she could study Japanese.

Similarly, when she quips, as she often does in interviews, that ‘I was one of the few prisoners who had all my teeth,’ or repeats her story about men of colour calling her ‘little sister’, it’s helpful to read the statements in the context of her writing, where Knox comes across as thoughtful and well informed about the systemic factors affecting incarcerated people. Context upends many of the judgments the world has made about Knox. When Time tried to account for her ‘unusual social behaviour’ by asking ‘Could Amanda Knox Have an Autism Spectrum Disorder?’, there was no consideration of the fact that she was raised by Edda, who, at her first Innocence Network Conference, encountered ‘a man named Johnnie Savory who’d been in prison for thirty years, and when he told her that he’d never seen the ocean, she said, “Well then, let’s go! Right now! Why not?” She … drove him out to the Oregon coast, and they ran barefoot into the Pacific together.’

A proud sci-fi and fantasy nerd, Knox inhabits the multiverse. She ‘fantasises about moving to a remote village in Germany and becoming a seamstress’; ‘If all else fails,’ she jokes, ‘I can make cuckoo clocks for a living.’ Elsewhere she seriously considers ‘alternative realities’. She returns again and again to the night of Kercher’s murder: ‘What happened to her could so easily have happened to me. If she’d been away that night, and I’d been home, would she have discovered the crime scene, would she have been wrongly convicted and would she be reflecting all these years later, happily married, feeling … both incredibly lucky and tremendously sad?’ When she met up with Sollecito in 2022, she wondered if he was imagining a parallel world in which ‘Meredith was never killed and we were never arrested … and perhaps these many years later, we were returning with our baby to revisit a place from our early courtship. I was certainly imagining that myself.’

Free is well paced, clear and focused, with chapter endings that are just shy of cliffhangers. Its early pages seem to reflect a younger self – words such as ‘castigated’ put me in mind of a bright middle school student – and the adverbs pile up: ‘Slowly, dejectedly’, ‘painfully and begrudgingly’. There are some unfortunate flourishes: ‘My sexual spark had been crushed like a cigarette beneath a polished Italian leather boot’; ‘His kindness rolled off me like rain off a stone statue in a deserted piazza.’ Knox settles down over the course of the book, as she gets further from the 20-year-old who might have written such sentences.

Free has received a warmer reception than her first memoir. This time everyone wants to be seen to be on her side. Some of the reviews and profiles have been written by journalists who have long-standing relationships with Knox and her family: in the Guardian Simon Hattenstone, who interviewed Edda while her daughter was still in prison and who has corresponded with Knox for years, announced, like a proud parent, that ‘she is married to Christopher Robinson … whom she adores, and they have two gorgeous toddlers.’ Joe Rogan, who first interviewed Knox during the pandemic (they bonded over their dismay at Kamala Harris’s history of suppressing exonerating evidence when she was a prosecutor), fell over himself during Knox’s most recent appearance on his podcast: ‘What all Christians aspire to is what you’re doing.’

There is an aspirational aspect to much of this coverage. For an article in the American magazine Mother Tongue, Hillary Kelly was invited into Knox’s Vashon Island home, which has a view of Mount Rainier and ‘a 1970s wood and laminate kitchen packed with hand-thrown ceramics; vivid Afghan blankets are tossed over log cabin furniture.’ The piece is accompanied by photographs of lush forest; the children’s lunch tray, artfully strewn with toys and a tiara; one of Knox’s ginger cats; and a painting of Knox with a gold halo by the one-time Jane’s Addiction guitarist Dave Navarro.

Free arrives at a moment of reckoning, as writers like Sophie Gilbert in Girl on Girl: How Pop Culture Turned a Generation of Women against Themselves reappraise the sleazy wreckage of the 2000s. (So much has changed for women in the public eye since Knox’s arrest in 2007, and so much hasn’t.) Knox is finally being written about by women her own age: ‘I’m a product of “Thong Song” and Girls Gone Wild, of Lindsay Lohan’s tabloid evisceration and giggling Monica Lewinsky sketches on Saturday Night Live,’ Hillary Kelly wrote. ‘I don’t know how to tell you Knox’s story without reverting to that moment, because somehow it became a moment about all of us women of a particular age.’

Not everyone is on board. In a piece for UnHerd called ‘The Creepiness of Amanda Knox’, Valerie Stivers described Free as ‘well written, persuasive and genuinely insightful’, but added: ‘It’s also occasionally tone-deaf in a way that seems to expose the reasons the story gripped us so in the first place.’ Stivers went to see Knox speak in Brooklyn ‘without lingering doubts about her innocence’,

and yet a strange thing happened: the longer she talked, the more it seemed possible that this small, cute, physically unimposing, nerdy-chic Seattle mom in platform boots could have done it. To be clear, I don’t believe she really did it. More important, there has never been any evidence that she did. But there is something about her affect and demeanour that gives off the eerie vibe that if any totally unlikely young woman could secretly be a crazed killer, it’s this one. The more she laughed and said how absurd it was, the more I could see why the police were suspicious. She mentioned some photographs [that] made her look like ‘a flippant psycho’, cackling at the ridiculousness to a crowd of fans, but that was exactly what she looked like in that moment.

The latest addition to the Knox media-industrial complex, The Twisted Tale of Amanda Knox, returns once more to Perugia in 2007. Grace Van Patten plays Knox as puppyish and earnest. Sharon Horgan maintains an appropriately stunned expression as Edda and Francesco Acquaroli captures Mignini’s bearish, dominating presence. Knox and Kercher are depicted as inseparable, which isn’t the way Knox herself (or anyone else) described them. The show itself is an oddly light confection – directly lifting whimsical elements from Knox’s favourite film, Amélie, and playing the initial miscommunications and petty grievances between different branches of the Italian police for laughs. The symbolism is often thunkingly obvious: at one point Van Patten lopes around Perugia in a red hoodie, just waiting to meet the big bad wolf. But the fairy-tale aspects of the show sit uneasily with its subject matter: murder, persecution, grief and suffering.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.