It was immediately clear when Martha, my 13-year-old daughter, died of septic shock that serious errors had been made. She died at Great Ormond Street Hospital, where a last-ditch attempt to save her proved futile, but the mistakes were made at King’s College Hospital in South London, where she had been treated over the previous five weeks. Before my wife, Merope, and I left Great Ormond Street early in the morning on Tuesday, 31 August 2021, the consultant in charge of Martha told us he had been alarmed by her condition when she arrived and wasn’t prepared to sign a death certificate. In such situations, the case is reported to a coroner and a postmortem arranged.

Nine hours earlier, Merope and I had been in the ambulance that sped north through the city to GOSH. I held Martha’s head in my hands; her eyes were taped shut, her body was swollen and discoloured. Now we took a taxi back to King’s to pick up possessions from her cubicle on Rays of Sunshine ward – presents she’d been given, her pyjamas, her books. They were already in plastic bags in the office; another child was in the cubicle. The nurses asked us how Martha was and were shaken when we told them she was dead.

A couple of days later we spoke on the phone to one of the consultants at King’s. ‘This was a totally preventable death,’ Merope said. ‘I don’t disagree,’ he replied. On 7 September we received a call from the clinical director of child health at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, a paediatric consultant who hadn’t been involved in Martha’s treatment. He had attended a ‘rapid review’ meeting at which her death was discussed, and told us it warranted a ‘Serious Incident investigation: red level’ – the highest category. The purpose of such an investigation is to establish causes and contributory factors, and to recommend improvements. (NHS England provides a list of ‘serious incidents’; at the top is ‘unexpected or avoidable death’.)

At the end of July, Martha, completely healthy and riding a bike on a family trail near a beach, had skidded on sand, fallen and lacerated her pancreas: she landed with force on the end of the handlebar and her pancreas was pushed against her spine. It is a nasty injury, but far from unknown in children, and is treated in hospital by liver specialists: she was taken to King’s because it has one of the three paediatric liver units in England, and is in London, where we live. Children with pancreatic trauma have been referred there for decades from all over the country; the director of child health told us that no other paediatric patient on record had died of the injury at King’s. We asked him why she was the exception, and he spoke of missed ‘opportunities to intervene … There were signs.’ He acknowledged that Merope and I hadn’t been listened to when we told staff we were concerned that Martha’s condition was deteriorating. ‘I am truly sorry,’ he said. Lessons would be learned. He told us the Serious Incident (SI) investigation would give us answers, but afterwards it was open to us to take the matter further, to the General Medical Council (which considers individual doctors’ fitness to practise) and the Care Quality Commission (which inspects, and occasionally prosecutes, hospitals). There was, he went on, ‘a full set of escalations’ we could make. Welcome to my last four years.

At the time, I paid little attention to what he said about escalations. I was in a stupefied state, and remained so for many weeks. I grasped that an unthinkable injustice had been done to my daughter, but had no thoughts about the possible consequences for the hospital or the doctors involved. What I wanted was a detailed explanation of what had happened to her. The director of child health told us that the SI investigation wouldn’t ‘gloss over anything’. ‘We will share everything with you,’ he said. It didn’t end up that way. Much of the work to get a full explanation would be mine.

During the nearly five weeks Martha spent in hospital, I had never once conceived of the possibility of her death. The doctors assumed she would recover and the question on ward rounds was how many weeks of school she might miss. She was in pain, but was visited by friends, watched TV and played video games. Rays of Sunshine was never hectic or a place of chaos with beds in corridors: the nurses told me it was well-funded and prestigious. We knew that the paediatric liver service at King’s was the largest in Europe and that the trust publicised it as ‘world class’; Martha seemed to be in safe hands. The most serious consequence we had in our minds was that she might become diabetic, but the doctors said her treatment would almost certainly avoid that.

Despite their confidence, we could see that Martha was getting sicker. During the final ten days of her life she had an infection that never went away, and the doctors couldn’t identify the source. On Wednesday, six days before she died, she started to bleed from the PICC line in her arm and the tube in her abdomen: her pyjamas and sheets were soaked in blood and for 48 hours the doctors were unable to stop the bleeding; they eventually filled her with blood-clotting products, dealing with the symptom but not the cause. We didn’t realise and weren’t told that the bleeding was a serious complication associated with sepsis, the over-reaction of the immune system to infection; we were pacified by a consultant’s comment that it was ‘a normal side-effect’.

Merope and I alternated 24-hour shifts by Martha’s bedside. On Friday the fever that had set in the previous weekend was still raging; she was in tears that afternoon, shaking, shivering and feeling desperate just when, as the trust later admitted, the care for her became more relaxed. ‘I can’t afford for them to make a mistake,’ she said. The ward was always eerily quiet at weekends, with the senior doctors leaving for home at lunchtime to be on call. ‘I’m worried it’s the bank holiday weekend, she’s going to go into septic shock, and none of you will be here,’ Merope said to the duty consultant at lunchtime on Friday. She said it in part superstitiously, summoning the worst to dispel its power. The consultant replied that she wasn’t worried about sepsis. We believed what we were told: that the broad-spectrum antibiotics would work and Martha would ‘turn a corner’. But on Saturday, my day with her, she became dizzy and could hardly stand.

On Sunday morning she said she felt ‘under attack’ and was dreading the day ahead. ‘What if the antibiotics don’t work?’ she asked. Her medical notes say she was ‘rigoring, pale, clammy and vomiting’, with tachycardia, fever and hypotension (that’s what made her dizzy). After I left that day, the low blood pressure became a cause of real concern. On the mid-morning ward round, we were later told, the doctors thought Martha was ‘clearly septic’, but nothing was said to Merope. Martha was given a small infusion of IV fluids – to improve cardiac output – but this had only a transient positive effect before her blood pressure dropped again. No new antibiotics were tried. Then at lunchtime she developed a rash, which soon spread all over her body. The nurse who knew Martha best recognised this as another clear sign of deterioration. Anxious about the rash, Merope again raised the subject of sepsis. The registrar made observations, concluded the rash was caused by a drug reaction and contacted his colleagues in dermatology, but too late – he left it until after 5 p.m. – for her to be seen that day. (The next morning there was no doubt that she had a sepsis rash.) Another small infusion of IV fluids in the late afternoon again failed to raise Martha’s blood pressure for any length of time. In the evening, at 10 p.m. and 11 p.m., she still had fever, tachycardia and hypotension as well as the rash. Overnight, Merope told the nurses Martha was drinking lots of water, but always wanted more.

Then, in the early hours of Monday, Martha collapsed when trying to get up. I later learned this was the result of cerebral hypoperfusion, a signal of septic shock. Knowing only rough details, sent in a text from Merope, I assumed it was a simple fainting spell. I arrived at the hospital in the morning expecting it merely to be another very difficult day for Martha on the ward, but she had just been intubated and put into a coma in the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU). We were told a couple of hours later she was very likely to die. I was so taken aback that I inanely replied: ‘You’re joking.’ Of course, what I meant was: ‘No, that’s not right. It’s not possible. You can’t have let that happen.’

When I spoke to the director of child health, the question I should have asked was: why hadn’t Martha been moved to PICU in the middle of the week, when she started bleeding? (He had just told us that the bleeding was a crucial development.) But I didn’t ask that question because I still didn’t realise that keeping her on the ward was the most significant error in her treatment. I had never spoken to the doctors about Martha being moved to PICU, and they never mentioned it as a possibility. Trying to work out what had gone wrong, I focused on whether Martha should have had major surgery rather than the conservative treatment advocated by King’s, and on her death coming right after a bank holiday. I wanted to know why a different consultant had seen her every day and why there hadn’t been someone with overall responsibility for her care, a person we could have talked to when everything was getting worse.

I recalled that on the Saturday morning ward round the duty consultant, who that day was the director of the paediatric liver team, had seemed unconcerned, despite Martha’s recent bleeding and continuing fever. ‘Infections come and go,’ he told me. At the front of my mind was the disappearance of the duty consultant on Sunday, who didn’t see Martha after midday, despite her further deterioration. I wanted to know why no resident doctor (until a year ago they were known as junior doctors in the UK) had reviewed Martha after 5 p.m. on Sunday, despite her rash and worrying observations, or overnight, when she was so thirsty, was being sick and had flashes in her vision. No doctor set eyes on her for more than twelve hours, until 5.45 a.m., when she lost consciousness and Merope shouted for help. I had no idea why Martha had simply been left to enter a state of refractory shock. Acting on a friend’s advice, in mid-September I sent the director of child health an email asking to see Martha’s medical notes and the minutes of multidisciplinary team meetings at which her treatment had been discussed. It turned out that no minutes had been taken.

Before the SI investigation got underway, Merope and I were invited, early in October, to a meeting with a number of consultants at King’s, including the head of PICU and the consultant who’d been on call on Sunday. This sort of meeting isn’t unusual, though it’s not always offered. It was the first time I fully grasped that there was a split within the team involved in Martha’s treatment, between the surgeons and the medical consultants on the ward. Conservative treatment of the injury Martha had involves a stent inserted endoscopically in an attempt to bridge the lacerated pancreas. Hers was a Grade IV transection, more serious than most, and in some circumstances treated with more invasive surgery, though no one told us it was an option.

One of the consultants at the meeting was a very experienced paediatric surgeon, a professor who I had been reassured to learn during our early days at King’s was the author of a paper on pancreatic trauma. I’m not sure how many days a month he worked at the hospital, but he had seen Martha during the bleeding. When asked to give an overview, he immediately made it clear he hadn’t been in charge of her treatment. I asked him what he would have done differently. He interpreted the question narrowly and said he would have done exactly the same. Martha’s sepsis and systemic inflammation wasn’t a problem for him, a surgeon, but for the medical team. When I tried to draw him out, he quickly grew irritable. The Sunday consultant raised the possible benefits of surgical intervention, and the two began to disagree. Martha had been dead for just over a month, and I couldn’t believe that the surgeon was fulfilling so zealously the stereotype of a grandee, showing no empathy for us as bereaved parents and bristling at a professional challenge. On the ward, he had happily told Merope about a research paper he was about to deliver in Athens: it was his first conference after lockdown and he was pleased to be back on the circuit. Having seen Martha in such a serious condition midweek, he hadn’t checked on her on Friday or over the weekend. I know senior academics who enjoy research but, as they get older, begin to resent having to teach students, and I wondered whether the equivalent happens in medicine. King’s later apologised for the manner in which the meeting had been conducted.

An SI investigation is carried out by the hospital where the incident took place: even in the case of a probably avoidable death, a trust is, at least initially, in charge of its own response, though the Care Quality Commission (CQC) is informed. A senior clinician at the hospital is asked to conduct interviews, gather statements, study the notes and write a report. Since 2014, the ‘duty of candour’ has legally obliged trusts to be ‘open and transparent’ with patients and their families when something goes wrong, but everyone agrees this is only patchily observed. Patients and families were for a long time excluded from the SI process, but trusts are now encouraged to involve them (to some degree) in investigations. The aim is to avoid the perception that everything is moving behind closed doors. Merope and I were asked to provide a timeline, and we met several times with the King’s intensive care consultant who was appointed to carry out the investigation.

When the SI report was being written, and we were arranging Martha’s memorial service, I began to read about other deaths in hospitals, and the ways in which trusts had responded. I noticed news stories that would have made me glaze over before Martha’s death: the world was now a very different place. I learned about what has been called the cover-up culture in the NHS, documented over decades by patient safety activists, the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman and (sometimes) the press. Until the end of the 20th century, there was an ingrained culture of silence, acceptance and defensiveness around preventable patient harm. There are still traces of that world: in 2023 the ombudsman’s office detailed 22 cases of avoidable deaths in hospitals over the previous three years that had not been adequately acknowledged or investigated, and it has issued warnings about attempts by hospital managers and doctors to bury evidence of poor care. (The national inquiry into maternity and neonatal services due to report by December is likely to reveal more evidence of such cover-ups.) I realised with relief that King’s seemed to be following the guidelines: sometimes trusts close ranks and no apologies are forthcoming.

I read about several incidents where medical notes had mysteriously gone missing. I followed the story of the response to the death of eight-week-old Ben Condon in 2015 after what the ombudsman called a ‘catalogue of failings’ at Bristol Children’s Hospital. Ben’s parents met with the trust, and recorded the meeting. When they were out of the room, staff admitted they had a case, and weren’t simply ‘misinformed’, ‘bolshy’ parents, but then realised such an admission might get the trust into trouble and talked about how to delete that part of the recording. In a report in October 2021, the ombudsman described the trust’s behaviour as a ‘deliberate attempt to deceive’. I had an intimation of how often such things happen when I learned from our SI meetings that the handover notes between the resident doctors on Sunday evening had disappeared. Who had removed them, and why? But we were still luckier than many other families: at least Martha’s death had prompted an investigation.

I was aware that my perspective on hospitals was becoming distorted. Fixated as I was on the catastrophe of Martha’s death, I lost sight of the countless examples of successful treatment in the NHS, the grateful patients full of admiration for the quality of care provided in difficult circumstances by hard-working doctors and nurses. I was now out of sync with almost everyone I knew. Friends later admitted they didn’t believe me when I said Martha’s death was preventable: it was just the grief talking, they thought, an inability to accept an unimaginable misfortune.

Healthcare professionals have a different frame of reference; they take it for granted that mistakes and failings are widespread in medicine. According to the PRISM studies carried out by researchers at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, there are between ten and twelve thousand preventable deaths a year in NHS hospitals in England (around one in twenty deaths), and more than three million recorded ‘patient safety events’ (a huge number go unrecorded, as doctors concede). The clinicians I have spoken to since Martha’s death are all too aware of the potential dangers; some of them have spent years working on reforms. The public has a sense of safety being eroded in the NHS by underfunding, short-staffing and crumbling infrastructure, but the (related) number of errors is not common knowledge. Medics are familiar with other problems that lead to failures in treatment: silo working and poor communication; toxic cultures in hospitals; gaps in training; resident doctors having to take too much responsibility; colleagues not being up to scratch; lulls in concentration. Meanwhile, the ombudsman claimed last year that some trust CEOs have encouraged him not to publicise the shocking examples of what can go wrong in hospitals on the grounds that it helps no one if the public loses faith in the NHS.

The SI report was completed at the beginning of 2022. It identified at least five occasions when moving Martha from the liver ward to intensive care, or getting a bedside review from a PICU doctor, would have been appropriate. One of these was the bleeding on Wednesday, a result, we discovered, of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), which indicated – contrary to what the consultant had told us – that her ‘treatment pathway’ was very far from usual: ‘Overt spontaneous bleeding from a coagulopathy thought to result from systemic sepsis is a very rare occurrence and a major cause for concern,’ the report stated. Martha also had ‘an unexplained pericardial effusion’ (a build-up of fluid around the heart), another sign of sepsis, but again Merope and I hadn’t been told, and an ECG was postponed until after the bank holiday. (There was enough fluid at the time of Martha’s eventual admission to PICU that it required emergency drainage.)

In a meeting the author of the report made clear to us the ways in which levels of observation and the nature of treatment – drugs, procedures, approach – would have been different had Martha been moved to PICU. There is one nurse to every patient in intensive care; readings are taken more frequently; consultants are present at weekends. In terms of treatment, there would have been more scanning, different and stronger drugs to stabilise Martha’s blood pressure or modulate her immune response, and so on. Of her rash on Sunday the SI investigator said to us: ‘This is about a rash in a young woman who was profoundly unwell, had sepsis that was unexplained, high fever, low blood pressure, racing heart – in context, those things by themselves are enough for admission to a high dependency facility. The rash on top of that … just goes to reinforce that this is the place she should have been.’ The report referred to the hospital’s use of a Bedside Paediatric Early Warning System (BPEWS) intended to help identify children at risk of deterioration. At King’s, a sustained BPEWS score of four triggered some form of escalation. Martha’s BPEWS score at 5 p.m. on Sunday was eight. She stayed on the ward. Her low blood pressure readings alone should, according to the hospital guidelines, have led to a review. They didn’t.

Two features of the set-up at King’s provide an explanation for the resistance to moving Martha to PICU. The first is the power of the liver team within the trust. The paediatric liver service brings in money from foreign patients, including children needing transplants. Its prominent consultants, many of them professors, attract research money. The status and international renown from which I had taken comfort when Martha arrived on Rays of Sunshine turned out to be problematic. The director of child health told me in a meeting that the liver team is ‘very hierarchical … they feel they know more than they do … they’ve been doing this their way for a long time.’ Although the registrar on duty on Sunday could have insisted that Martha be moved to intensive care, the ward’s strict escalation protocol meant that he was always going to defer to the consultant on call, whom he phoned twice at home and who formed the opinion that Martha shouldn’t even be reviewed by the PICU team. Accustomed to treating post-transplant patients and others with complex needs, the liver team thought of their ward as itself a kind of high dependency unit (HDU). A senior nurse who had worked on Rays of Sunshine for decades had thoroughly absorbed the prevailing culture and underlined in her SI interview that staff on the ward were considered ‘able to deal with HDU type of patients’. (This nurse, even after Martha’s death, was resentful of Merope and me for looking things up on the internet and not trusting ‘their expertise’. She said: ‘They were always … asking “what if?”’)

The second feature follows from this: the SI report found that relations between the liver team on Rays of Sunshine and the doctors in PICU were poor. The high-status liver consultants had long questioned the value of PICU patient review, especially if the doctor carrying it out was even slightly less senior than they were. It became clear that they didn’t like relinquishing control and thought of referral as a failure. I had no idea that the status of a team within a hospital could affect care to such a degree. It seemed to me a situation that was always likely to result in a serious incident, even a fatality: Martha was unlucky enough to be the patient affected. The lack of co-operation dated back years: even the reporting of Martha’s death as an SI was delayed because each team left it to the other.

SI reports are not published or widely available, even within the NHS. No doubt this is in part because so many are produced: more than twenty thousand serious incidents are investigated every year. But it appears also to be a vestige of 150 years of professional self-regulation, which came to an end as recently as the 1990s. There is still an assumption that difficulties should be dealt with quietly and privately by a trusted caste of physicians: after an incident, even an avoidable death, hospitals and doctors are usually relied on to correct themselves. The report identified the need for improvements at King’s, including a new emphasis on the importance of parental concern. It also recommended exploring the introduction of a ‘critical care outreach team’ for paediatrics: specially trained nurses and doctors who would monitor patients and act as a link between the children’s wards and PICU. These are common in large hospitals and such a team was in place for adult patients at King’s. Its absence in paediatrics seems to have had some connection with the influence of the liver team, and the perception that it had sufficient expertise never to need co-ordinated PICU back-up.

The SI report confirmed that no clinician had overall responsibility for Martha’s care, so no doctor was alert enough to the trends in her observation figures; instead, a different consultant every day regarded her condition as a new normal. (All the medical consultants I encountered, with one exception, were men, which is unusual in paediatrics.) That no one felt responsible for her proved to be disastrous. A key recommendation arising from the report of the Francis Inquiry into the Mid-Staffs scandal, published in 2013, was that every patient be assigned a ‘responsible consultant/clinician’ and ‘named nurse’, with the names visible at the patient’s bedside; the government sent a directive to every trust. But it wasn’t in place on Rays of Sunshine; presumably it didn’t suit the way the liver consultants wanted to work. I realised what patient safety campaigners have wearily reiterated for years: hospital scandals lead to inquiries, which lead to reports that produce a set of recommendations, which are ignored or not implemented, with no consequences.

Two fundamental principles underlying the way SI investigations are conducted have their origin in the work of the British psychologist James Reason. Within a few weeks of Martha’s death I had been told numerous times by doctors about the ‘Swiss cheese model’, developed by Reason in his book Human Error (1990) to explain how accidents occur. It is used in aviation and engineering as well as healthcare. Slices of Swiss cheese represent a system’s barriers or safeguards against accidents – such as policies and training. Each slice will have a hole or holes, representing weaknesses; a serious accident happens when the holes in different slices are aligned. Because they tend to be in different places in each slice, safety is usually maintained, but with Martha the holes lined up. This model has become a cliché in medical schools and at patient safety presentations; it was mentioned to me as a reminder that hospital systems are complex and explanations of deaths such as Martha’s are – to use a word heard oppressively often in such contexts – ‘multifactorial’.

The second principle is ‘just culture’ (a more sophisticated version of ‘no-blame culture’), which was fully developed in a later book by Reason, Managing the Risks of Organisational Accidents (1997). There’s a huge literature on just culture, which has become a kind of dogma in discussions of patient safety and medical mistakes. It centres on the idea that untoward incidents are almost always the result of faulty systems, cultures or training rather than attributable to individuals. To blame clinicians therefore isn’t fair, and it’s also unsafe, because it discourages doctors and nurses from speaking up when things go wrong, which is the first step towards making improvements. The notion of individual culpability is dismissed with condescension as the ‘old view’ of human error. If a doctor didn’t act with malice or wilfully take risks, the idea of blame or responsibility should be set aside. The Berwick review, commissioned in the wake of the Francis report and published in 2013, emphasised the need for cultural change in the NHS. Don Berwick, an American paediatrician and health administrator, argued that except in the rarest cases, there was a need to ‘abandon blame as a tool and trust the goodwill and good intentions of the staff’. Writing in the British Medical Journal in 2018 the NHS consultant David Oliver argued that public (as opposed to expert) debate ‘is obsessed with the notion that, when things go wrong in healthcare, this must indicate failures by individuals. In such a narrative, systemic factors … are seen as convenient excuses for individual error.’ He objected to ‘the clamour for accountability’.

SI reports deliberately don’t focus on identifying individual mistakes, because this is felt to lead to a ‘culture of fear’ rather than learning. The reports are anonymised, in part to protect the staff concerned. In The Golden Thread: Stitching Patient Safety into the NHS (2023), Philip Berry, another hepatology consultant, describes the usual approach of clinical investigators as ‘supportive’ of the medical staff, ‘forward-looking’, ‘soft’. All of this was true of the SI report into Martha’s death, though occasionally the importance of individual agency was hinted at. On Sunday evening the consultant, who had gone home in the early afternoon, spoke to the head of PICU about her, at the request of the registrar. According to the report’s summary, the consultant told him that ‘Martha was stable, with a normal lactate [and] blood pressure … no bedside review was necessary or should be undertaken.’ The head of PICU was clear that he had been told the call was ‘for information only’; Martha ‘categorically’ did not require a review.

In his interview for the SI investigation, the head of PICU’s recollection of the conversation was even starker, but his wording was left out of the report (I saw it after making a Freedom of Information request). He said the Sunday consultant’s message had been: ‘The last thing I would want is for the ICU team to go to the ward to see [Martha], as the parents will get more stressed.’ (Hospital guidelines in fact suggest that increased parental anxiety should be a factor when considering escalation.) The head of PICU noted that ‘this was the only time in my career as a consultant at King’s that I had been actively told not to see a potentially unwell child.’ He happens to be the hospital’s leading expert on sepsis and he works just down the corridor from Rays of Sunshine, but the liver doctors never sought his advice.

Iunderstood that SI reports avoid holding individuals to account, but I wanted to know more. Why had we never been told Martha had sepsis? Considering that she was being treated for a worsening of the condition, and not responding as hoped, why did the Sunday registrar (who referred to Martha as ‘Millie’ in his notes) not see any spreading rash as a red flag? And given the duty consultant had been told by the registrar over two phone calls that Martha was febrile, hypotensive, had a new rash and an increase in her lactate level (a further sign of worsening sepsis), why had he not come into the hospital? The risk was obvious. (‘If you don’t look at a patient,’ one doctor told me, ‘you’re not going to know what’s happening’; another said that ‘harm is usually thought of as an act, but can also be an omission.’) Having been asked by the registrar to contact PICU, why did the consultant wait an hour and ten minutes before making the call, only to say very definitely that no review was necessary? The SI report, however thorough, provided an internal, system-oriented version of events, which raised as many questions as it answered. The nurses had identified the PICC line in Martha’s arm as a potential source of infection, but it hadn’t been taken out: why not? (The report saw this as a ‘missed opportunity’, but put no name to the decision; its removal was one of the first things that happened when she finally made it to PICU.) The observation numbers taken by a nurse at 10 p.m. and 11 p.m. should by themselves have triggered a PICU review: why then did neither of the doctors on the ward, the registrar or the senior house officer – a less experienced resident – do anything in response? Why did the SHO who was on duty that evening and overnight not go to see Martha at all before her collapse the next morning?

When we asked these questions in meetings, the SI investigator led us towards some partial answers. Sepsis training wasn’t mandatory at King’s, none of the liver team did it, and none of the residents looking after Martha that weekend had seen a sepsis rash before. (The hospital also didn’t have a paediatric sepsis lead, a designated clinician whose job is to improve sepsis care.) Looking at the rash, the Sunday registrar was reminded of something he’d seen in a previous patient and thought Martha might have an extreme (and rare) drug reaction called DRESS syndrome. Despite this diagnosis, her physiological disarray and the increase in her lactate level at 5 p.m., he somehow didn’t register her condition as an emergency and didn’t review her again. In his second call to the consultant, mid-evening, he focused on Martha’s ongoing fever and raised the possibility of a move to intensive care. Perhaps he then felt he had done his duty: PICU would turn up if his superior felt it necessary. (The registrar left the ward to go to the on-call room just after midnight.)

The SI investigator said that the decision of the SHO not to check on Martha overnight was ‘inexplicable’ given that she had been told at handover that Martha was ‘the sickest patient on the ward’. She wasn’t over-stretched (the ward wasn’t full). Her explanation was that she had been told at handover that Martha was ‘stable’ and neither the day team nor the nurses had requested that she review her. A basic part of her job was to monitor the nurses’ observation readings, but despite the obvious worsening of Martha’s condition during the evening, she did nothing. No doubt she also thought that any escalation was the decision of the consultant on call.

As for that consultant, those present at the SI meetings felt that he shouldn’t have resisted a critical care review for any reason, and certainly not on the basis that it might increase parental anxiety. The director of child health said ‘we can’t understand his logic’ and was in no doubt that the consultant had ‘made a clear and obvious mistake’. He also told us that the consultant himself believed ‘he made a mistake.’ But not long afterwards the SI administrator sent me emails that changed this picture. I was told, twice, that the consultant insisted he had said no such thing.

After the SI report was produced, Merope and I were invited by King’s to another meeting with consultants so we could ask them face-to-face about anything we still didn’t understand. I also wanted to meet the Sunday registrar and the overnight SHO, but this request was denied: ‘We are not going to enable that,’ the director of child health told me, ‘they’re in training.’ The protection of resident doctors is customary: after a serious incident, even a preventable death, they are expected only to make a statement, discuss the SI report with their educational supervisor and reflect on what happened. Meetings with families are usually left to consultants, and I could understand the reasons for this protocol, but the registrar was about to become a consultant – not really ‘in training’ any more – and no one else could explain exactly what had happened. The two residents were thought experienced enough to be left on the ward to look after a critically ill, deteriorating child; I hoped they might give their version of events in person.

The SHO was an ST3 – she was in her third year of specialty training (her fifth year out of medical school). The registrar was an ST8; it must have been his tenth year out of medical school (his specialty wasn’t hepatology, but gastroenterology more generally: he was towards the end of a six-month rotation on a liver ward, his last as a resident). There is a UK doctors’ community on Reddit, and in one thread a post offered reassurance to resident doctors involved in an SI process: the investigation is ‘not to place blame … This is not going to be on any permanent record, you may have to … reflect on it but that’s all. It won’t affect your career going forward.’ In any case, both the registrar and the SHO were now working at another trust so King’s couldn’t tell them to attend a meeting, or do anything. Recalling his time as a resident, moving between placements, one non-King’s consultant told me: ‘If I had made an error in my previous hospital, no one would have known.’

At the meeting with the consultants, the doctor on duty during the DIC bleeding (the only one who made any notes on the patient record) said: ‘I was treating Martha as having presumed sepsis from the beginning … I should have made that clear to you.’ She had never seen bleeding from both a PICC line and an abdominal site before, and acknowledged it was highly unusual in a pancreatic patient. It was a sombre, intense meeting, but the Sunday consultant, one of the many professors at King’s, again tried to avoid admitting he had made a mistake. I asked him whether, in the light of all of Martha’s symptoms and the two calls from the registrar, he had considered coming into the hospital. ‘No,’ he replied. He said he was under the mistaken impression Martha was improving (having focused on the transitory positive response to the second infusion of fluids). He said he didn’t remember the two calls in detail, but was adamant that the registrar’s reason for phoning him the second time was not to express increased concern. (He had no alternative explanation and it’s unclear why he said this.) Pressed on his decision not to involve critical care, he said: ‘You could escalate all sorts of things.’ King’s told me later that Martha’s death would be discussed by the trust’s Responsible Officer Advisory Group – these groups look into ‘the conduct and performance’ of doctors, according to NHS England – and that this consultant, who did not have a record of mistakes, would meet the trust’s chief medical officer to talk through what had happened. No more action would be taken internally. No one from any external medical body would talk to him about Martha’s case.

The inquest took place towards the end of February 2022 at St Pancras Coroner’s Court. It was scheduled to last only one day, which seemed insufficient, but there was a post-Covid backlog. Knowing an inquest was on the horizon, Merope and I had appointed a solicitor and, through him, a barrister: their legal costs would be covered as part of a claim we’d make against King’s. The solicitor also arranged the payment to us of the fixed statutory bereavement award. He told us that since children aren’t recognised in law as economic agents, their ‘value’ is very low. (The NHS can pay out millions in compensation for negligence involving stillborn babies, because the mother is regarded as the ‘primary victim’.) King’s sent a letter admitting to a breach of duty of care the night before the inquest began. Our solicitor rolled his eyes: he had seen this many times before, though the trust denied that the timing of the letter was an attempt to evade responsibility for our lawyers’ costs, which are no longer payable once the admission of a breach has been made.

An inquest sets out to determine the cause of death; the coroner doesn’t apportion blame. The clinicians had been asked, as is usual, to produce written statements explaining their involvement in Martha’s death. Giving evidence at an inquest is presumably a dismal experience for a doctor, however respectful the questioning; that they must do so represents a kind of accountability. The coroner decided not to call the SHO who hadn’t visited Martha overnight to give evidence, but I noticed that in her statement, which was read into the record, she had changed the explanation of her failure to see Martha from no nurse having asked her to do so to her receiving an instruction at handover to stay away. Our barrister asked the registrar in court whether he recalled any such instruction being given. ‘No, Ma’am, I don’t remember that.’

The director of the liver team, who had taken no action after the ward round on Saturday morning, now said Martha should have been in a high dependency bed weeks before her death. The Sunday consultant, despite the SI report, and despite the registrar recognising at the inquest that PICU should have become involved at 5 p.m., again refused to admit that keeping her on the ward was a mistake. (‘There wasn’t an indication to move her … and I haven’t changed my opinion really on that.’) He claimed that the decision not to arrange a review had been taken jointly with the head of PICU, and said, too, that parental anxiety had not featured at all in ‘the decision-making process’ (both claims contradicted the head of PICU’s SI interview). ‘Do you think that if you had had a referral presented in a more systematic way, if you had sent a registrar to go to review Martha, she would have been admitted to paediatric intensive care?’ the coroner asked the head of PICU. ‘Without a doubt, 100 per cent,’ he replied.

At the end of the proceedings, the coroner said that Martha had been ‘incredibly unlucky’: ‘How many children have fallen off their bikes with no significant consequences?’ Her conclusion, which echoed the testimony given in court by the SI investigator, was that ‘the likelihood is if she had been transferred to intensive care [earlier] she would have survived.’ This was a relief: it was legal recognition that it was an avoidable death. King’s gave a brief statement, which ended: ‘We are committed to delivering further improvements to the care we provide.’ The coroner was concerned enough to write a Prevention of Future Deaths report – these reports are issued after only 1 per cent of inquests – saying that there was a need to improve the relationship between the children’s liver team and PICU at King’s. Recipients of a PFD statement must respond in writing within 56 days, but, to the consternation of patient safety campaigners, are not compelled to take steps to address the problems. Hospitals are, as usual, trusted to take the necessary action.

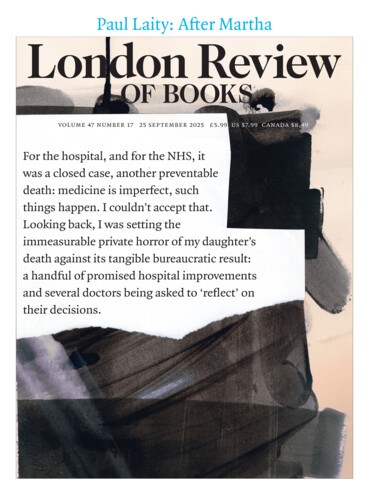

Following the inquest, Merope and I realised that the only way the actions of the doctors who’d been involved in Martha’s case that Sunday might be investigated was if we referred them to the GMC. The NHS had no mechanism to hold them accountable. I understood the principles of just culture, but found it dismaying that there was no other way to get answers to questions about glaring errors in patient care that would help us to understand how Martha died. For the hospital, and for the NHS, it was a closed case, another preventable death: medicine is imperfect, such things happen. I couldn’t accept that. Looking back, I was setting the immeasurable private horror of my daughter’s death against its tangible bureaucratic result: a handful of promised hospital improvements and several doctors being asked to ‘reflect’ on their decisions. Rightly or wrongly, I felt that the death of one’s child was an experience that almost certainly went beyond anything in the lives of these clinicians. It seemed unlikely to me they would have allowed their own children to be left on the ward as Martha had been. I realised I didn’t fully appreciate the messy realities and frustrations of working on an NHS ward, and knew too that there was a widespread feeling within the profession that raising concerns with the GMC would be inappropriate because the doctors didn’t set out to do harm. But the issue seemed to me less straightforward, involving questions of competence, complacency and consequence.

In The Golden Thread, Berry considers the difference in perspective between a grieving family member and a healthcare professional after an avoidable hospital death. Whereas the family member sees ‘neglect’, Berry assumes that ‘nobody came to work to do a bad job, but … the system in which they worked was inherently unhelpful.’ Although ‘intellectually, depersonalising culpability is clearly the only constructive way to proceed,’ he writes, ‘emotionally it may push grieving families away.’ I didn’t think my position was based wholly on emotion. It seemed obvious to me that individual errors could exist alongside system failings; both needed to be explored. I wasn’t thinking in terms of blame, but I was thinking about responsibility and the potential risk to future patients.

When patients or families insist on attention being paid to individual error, they risk accusations that they are irrational and unscientific, and that they hold a grudge against the medical profession. In a 2020 article in the Journal of Medical Ethics on no-blame culture, Elizabeth Duthie and her co-authors wrote about a ‘real-life example’ of a nurse who met a patient’s family after she had made a mistake. The nurse was ‘remorseful, traumatised’, though the error had led to ‘no harm’; the patient’s wife was aggressive and unreasonable, and had made threats. The choice of scenario is telling in a way the authors didn’t intend. They slip into generalising about the ‘values that patients and families bring’ to discussions of error, and imply that unqualified people rarely understand what it means for a medical professional to work as part of a team and within a system.

Just culture is supposed to prompt the question: would averagely competent doctors have acted similarly in the same circumstances? (This is known as ‘the substitution test’.) I didn’t know the answer to that question in Martha’s case, but I hoped not. More important, no one within the NHS, certainly not King’s, had conducted or even considered conducting such a test or assessment of the doctors’ actions in relation to Martha’s death. The accepted approach is that no individual should feel implicated: the lens is always trained on the clinicians’ future, the fate of the patient all but forgotten. So in March 2022 Merope and I decided to send a letter to the GMC raising concerns about the Sunday consultant, the registrar and the SHO. There are legions of aggrieved patients and family members or friends who don’t have the resources, whether of time or emotion, to do this; in such cases, the possibility that individual responsibility will be considered disappears.

The GMC registers and regulates all UK doctors, who pay the fees that fund it. In my dealings with GMC officials I was constantly reminded that its role isn’t to punish a doctor for errors, but to assess whether they are currently fit to practise; in making this decision, its purpose is to uphold standards and maintain public confidence in the profession. Sanctions will of course be imposed on doctors who are ‘deliberately malicious or wilfully negligent’. Some are referred because of a recognised pattern of poor performance. If a single incident is in question, the GMC, as its former head Niall Dickson has emphasised, takes a ‘softer line’. Every complaint is assessed, and if it meets the criteria for a fitness to practise issue, the GMC will conduct a provisional inquiry to establish whether a full investigation should be carried out. Over the past couple of years, under 10 per cent of complaints have led to an investigation. At the end of April 2022, I received an email letting me know that the GMC was making provisional inquiries into the three doctors.

All doctors get things wrong. What matters hugely to families in our position is that they have the courage and humility to admit to these mistakes. If they do, it transforms the way you feel about a clinician: any idea of restorative justice depends on an acceptance of responsibility. Merope and I know a couple whose two-year-old daughter died of sepsis after serious errors were made; the doctor most involved in her care was brave enough to meet them to say he had personally failed and would never forget it. The GMC, too, is supposed to set great store by the way a doctor responds to their own failings. A finding of ‘impairment’ is less likely if a doctor can show that they have admitted error, ‘reflected’ (that word again) and learned from it. So why had the Sunday consultant asked for emails to be sent denying he had ever used the word ‘mistake’?

One reason might be that before the duty of candour was introduced clinicians were often advised never to own up to mistakes, or even to say sorry, because it was important not to admit liability. Such pressure came partly from management: individual hospital doctors don’t get sued, trusts do (sensibly enough, NHS healthcare workers themselves suffer no financial risk whatever happens to their patients, so long as they are not criminally negligent). There’s no doubt that trusts’ legal teams continue to have great influence, since compensation claims can be substantial in cases of serious harm or the death of an adult. An older generation of clinicians might hold to the traditional set of assumptions in this supposedly new era of transparency, but it’s not a simple generational divide: on social media plenty of advice posted anonymously by resident doctors says ‘do not admit to anything.’

Perhaps the Sunday consultant had another fear about the consequences of admitting error. When I met King’s doctors after Martha’s death, they referred several times to the case of Dr Hadiza Bawa-Garba, a paediatric registrar at Leicester Royal Infirmary who in 2015 was given a two-year suspended sentence for gross negligence manslaughter following the death from septic shock of six-year-old Jack Adcock in 2011.* (She was struck off the medical register, a decision that was later overturned on appeal.) Her conviction – she was led out of the court wearing handcuffs – sent shockwaves through the medical profession, which were clearly still being felt around the time of Martha’s death. There is no doubt that Bawa-Garba made serious mistakes: she missed obvious symptoms of sepsis and stopped the crash team from resuscitating Jack, having mistaken him for another patient. But as other doctors pointed out, system failures, not least understaffing, received insufficient attention at the trial; Bawa-Garba was doing the work of two residents. (The consultant under whom she was working escaped official censure.) During the trial, the prosecution barrister appeared to use her recognition of what she had got wrong against her. Did the Sunday consultant become concerned that, however improbable it seems, the police might come knocking on his door? Cases of gross negligence manslaughter involving medics have always been extremely rare and became even more so after the backlash from this case. But I could see why manifestly inappropriate criminal sanctions for a clinician who had no malicious intent might have caused a frisson for the doctors at King’s and contributed to their fears of being held to account.

The Bawa-Garba case is an outlier, but it’s easily cited by those opposed to pursuing individual responsibility, as if prosecution were always a likely outcome. Jeremy Hunt, the former health secretary, wrote a book called Zero (2022) about unnecessary deaths in the health service, which repeats the usual line that the best way to prevent another case like Bawa-Garba’s is to end blame. On the Today programme last December, Hunt reprised his view that there was a need for ‘an open culture … where people feel they are able to say’ if they got something wrong. ‘One of the reasons there are so many cover-ups in the NHS’, he continued, is that doctors worry that if they admit to an error ‘they’ll get fired.’ When he was asked about accountability he responded: ‘If someone turns up to work and does an operation when they’re drunk, no quarter should be given. But … if you create a culture where admitting to the tiniest of mistakes means you get punished from an almighty height, then people don’t want to admit to them,’ improvements aren’t made ‘and patients die’.

What struck me about this interview were the examples Hunt chose. No one disputes that a surgeon who is habitually drunk in the operating theatre should be sanctioned. And no one would ever suggest that a doctor who admits to the ‘tiniest’ of mistakes should be punished from ‘an almighty height’ (which never happens in any case). But what about the more difficult territory in between? What if a senior doctor’s poor decisions are not wholly attributable to system failings, might arise from complacency and contribute to a preventable death? And even if a robust ‘culture of learning’ is in place, is it likely that all errors will be enthusiastically owned? As the philosophers Joshua Parker and Ben Davies point out in a blog on blame and responsibility, there ‘will always be disincentives to owning up when you have risked a patient’s health. A no-blame culture cannot negate a doctor or nurse’s embarrassment or guilt at having risked a patient’s safety; in some cases, this will provide a motivation not to admit culpability.’ When I raised this issue with the CEO of King’s, he responded: ‘It is almost certainly true that some individuals may be concerned about the consequences for them if they do [admit mistakes]; this will be based on a number of factors … among which will, I am sure, be the impact on their career.’ He mentioned ‘the need for honesty and humility’. In the aftermath of Martha’s death, it would become clear that not only the Sunday consultant but the SHO too were reluctant to admit they had done anything wrong. As part of a discussion of mistakes in Zero, Hunt himself refers to the ‘instinct for self-preservation’.

In April 2022, Merope and I wrote to King’s enumerating the questions unresolved by the SI report. We pointed out that because everything had been dealt with in-house some issues hadn’t been addressed. The next month I met the chief medical officer, who told me the trust had decided to commission an external investigation into Martha’s death, to be conducted by two consultants from Birmingham Women’s and Children’s Hospital, which has the biggest paediatric liver department in the country after King’s. We hadn’t explicitly argued for this, and it was welcome as another form of accountability. The chief medical officer told me, as if to explain my motivation, that ‘bereaved parents [typically need] longer processes than usual SIs’: ‘losing a child is one of the hardest things to go through, but losing a child through a medical accident is even harder.’ She also admitted, contradicting a claim made to me by a King’s consultant, that, for inpatients, ‘we do not have the same care at weekends and bank holidays.’ While NHS clinicians often concede this in private, they tend not to do so in public.

When I asked her who was responsible for Martha not being seen by a doctor after 5 p.m. on Sunday, she replied: ‘I can’t possibly give you that.’ She did, however, say that the Sunday consultant had finally admitted what she called his ‘terrible error in not escalating Martha to critical care’: he had sat with her and said, ‘I know I made a grave mistake.’ He had also regretted having been ‘obstructive’ about admitting it. The chief medical officer later confirmed that ‘he has now genuinely realised that if he had acted differently, Martha would have been admitted to PICU earlier … and that on the balance of probabilities she would not have died.’ But he would later change his position again.

That September, a year after Martha’s death, Merope wrote about what happened in an article in the Guardian, which drew on what she had learned from the SI process and the inquest. According to Berry, ‘tens of thousands of NHS employees read it and thought about it.’ This was a different kind of accountability, unavailable to almost everybody, but possible in this case partly because Merope is a Guardian journalist. She received dozens of supportive responses from doctors and nurses, many of whom said they were not surprised at what had happened. ‘After decades in the NHS,’ a surgeon wrote, ‘I have observed that teaching hospitals … often attract “high fliers” for whom career progression may appear more important than team working and basic medical care … In some units, consultants are still gods.’ An intensive care director of many years’ standing wrote that ‘it beggars belief that doctors let [Martha] progress to severe sepsis, altered coagulation, a seizure and septic shock before taking her to PICU … Doctors are not heroes and have variable ability.’ Merope’s piece attracted attention in part because the failings it outlined couldn’t easily be attributed to a lack of funding or resources; it embraced but also moved beyond the usual, reliable (and important) systemic explanations. Merope made pointed criticisms of the (unidentified) clinicians involved, including the two Sunday residents, and this unsurprisingly proved controversial within the profession. The UK doctors’ Reddit threads included sympathetic and informative posts, but also revealed a lot of anger: ‘absolutely insulting and unacceptable … should never have been allowed’; ‘There is nothing to learn from this’; ‘vindictive’; ‘had to skip almost every other paragraph just to put together a semi-consistent discharge summary’; ‘frankly disgraceful’; ‘there is nothing to blame here apart from the fates.’

Before finishing their external review, the Birmingham consultants were sufficiently troubled to send an interim alert to King’s raising safety concerns, among which was that relations between the paediatric liver team and PICU had now completely broken down. They delivered their report in November and asked the trust for the findings to be disseminated throughout the NHS, which of course didn’t happen. They spoke at length with Merope and me at two online meetings. Afterwards, I felt reassured that raising concerns about individual doctors with the GMC had been justified: we had recently been informed that all three were to be the subject of investigations.

The external review also gave a sharper outline to the systemic and cultural failings at King’s. On the issue of documentation, one of the Birmingham reviewers said to us: ‘Where do I start? Where is it?’ No records existed of the consultants’ conversations about Martha. There was ‘no plan’ laying out what to do when her pathway diverged from the normal, they told us, and ‘complete disagreement between hepatology and surgery’ as to ‘who was the primary team responsible’ for her care. Nobody ‘managed the patient’. These issues cast into relief the need for a single ‘responsible clinician’, and I asked the reviewers whether named consultants with tangible responsibility existed at their hospital. ‘Yes,’ they replied, adding that they had believed ‘foolishly’ the practice had been introduced everywhere.

The second, and related, issue was hierarchy. Nurses on Rays of Sunshine had marked Martha as being ‘at risk’ on their system during her DIC, but no doctor was aware of this. (One nurse recalled in her SI interview she had been saying for days that Martha was not ‘supposed to be on this ward’.) According to one of the Birmingham consultants, some of the nurses ‘could see she was getting lethargic even on Thursday. You saw it on Saturday. Nurses who saw her day in, day out could see the trend.’ There was, she continued, ‘high-handedness’ on the part of the liver team and no recognition that the hierarchy was ‘not ok’. The psychologist Michael West describes medicine as more hierarchical than the military, and, at its most insidious, a steep hierarchy can erode any sense of agency or responsibility on the part of even experienced nurses and resident doctors. The days of hospital canteens with a section reserved for senior consultants, like an Oxbridge high table, are supposed to have gone for ever. But change is slow.

The Birmingham consultants talked about the liver team’s resistance to a critical care review; they told us it ‘was ingrained in the culture there that asking for help was somehow a sign of weakness’. The dismissive attitude of the liver consultants to their less senior colleagues in PICU had, they discovered, ‘been raised frequently and repeatedly before Martha died’. Keeping the equivalent of high dependency patients on Rays of Sunshine wasn’t safe because the ward was ‘not staffed or trained to do that’.

The final issue was diagnosis. The reviewers said during our meetings that both parts of Martha’s pancreas remained healthy: it would have healed. But the King’s consultants hadn’t paid the right kind of attention midweek to Martha’s dysfunctional inflammatory system. They thought they could manage a ‘child/infection in the same way that they managed it with acute liver failure or post-transplant’. This was to me the most revealing and significant perception about the King’s liver consultants: they were very confident of their ability to treat complex patients on the ward but failed in their response to Martha’s particular condition and trajectory, with no doctor taking enough care or paying enough attention to pause, think about whether the usual treatment was appropriate and take responsibility for making a change. Martha gradually deteriorated over at least a week and every consultant who saw her merely hoped for the best, despite the warning signs, and passed the buck to the next day’s doctor. In the Birmingham reviewers’ opinion, Martha should have been moved to PICU during the DIC and treated with immunomodulatory therapies: ‘It is gut-wrenching that she didn’t even get those first or second-line treatments.’ There had been ‘a litany of heartbreaking failures’, they told us. ‘We have been asked to do case reviews before and have never been as categorical.’ Their report identified ‘serious systemic issues’ and ‘a departmental and trust responsibility for the care failings’. We decided to contact the CQC.

Early in 2023, Merope and I attended a final meeting at King’s, which involved the CEO and two other senior managers, one of them a liver consultant who had seen Martha during the DIC and was the new director of child health. We wanted to discuss causation, culture, ‘trust responsibility’ and issues such as silo working and hierarchy that had been raised in the external review. Very few bereaved relatives get to talk about these issues with hospital executives: we appreciated the opportunity, and were benefiting no doubt from the attention paid to Merope’s piece in the Guardian.

The CEO was uncomfortable answering questions he hadn’t been able to prepare for in advance. He expressed sympathy, but also became a little annoyed: King’s had admitted responsibility and initiated improvements – what more did we want? It was acknowledged again that the Sunday consultant had made a serious error (‘there’s no way [he] can redeem himself’; in his call to the head of PICU he was ‘grossly incorrect’), and it occurred to me that these managers would rather matters were deflected to the GMC than pursued by the CQC, which would investigate the hospital rather than the doctors. When asked to explain why we were never told Martha was being treated for sepsis, the consultant said that sepsis is ‘a big political word’, and conceded that doctors try to ‘manage the atmosphere’ on a ward.

To my mind this meeting marked a sharp turn for the worse in the trust’s response to Martha’s death. However solicitous they were, the executives refused to accept some of the findings of the external review they had commissioned. The CEO dismissed its conclusions as merely ‘an opinion’. The trust would later adopt the position, contrary to the Birmingham reviewers’ findings, that Martha shouldn’t have been referred to PICU at the time of the DIC bleeding. I had hoped for a more open and less self-protective approach. The trust’s argument ignored not only what some of their own clinicians had said but the admitted relaxation in Martha’s care during the bank holiday weekend. I believe its executives must themselves have realised that Martha’s chances of survival would have hugely increased had she been in PICU from midweek. The trust’s intransigence was therefore hard to face; it seemed petty, in fact deplorable. Despite having made some changes since her death, it appeared that King’s had learned almost nothing. As the ombudsman’s office has noted of the NHS as a whole, ‘senior managers and boards are more interested in preserving the reputation of their organisation than dealing with patient safety issues.’

I asked about the power of the liver unit within the trust. In the year 2022-23, according to King’s, the paediatric liver team brought in more than £3 million from private work, including transplants (it carries out more than sixty transplants on children – NHS and private patients – every year). In the five-year period between 2018 and 2023, liver consultants at King’s themselves earned £2.4 million from private patients, despite Covid. (Research is a separate revenue stream; some of the professors have links with pharma and biotech companies.) The rheumatologist Matthew Hutchinson has described the way that ‘pampered professors carve out fiefdoms’ at some prestigious hospitals. I had heard the term ‘special colleagues’ used – it refers to cliques of senior doctors so influential in a hospital that they are given unusual autonomy – and pointed out at the meeting that the head of the paediatric liver team is also the medical director of King’s Commercial Services Ltd; he has played a role in facilitating King’s College Hospital units overseas, in Abu Dhabi, Jeddah and Dubai. The executives denied that he was particularly influential within the trust, but said the liver team is seen as a ‘flagship service’.

The patient safety expert (and airline pilot) Martin Bromiley believes there is a lack of oversight of influential consultants within hospitals: ‘You have people in charge with no process for reviewing or observing them. They are allowed to just go off and practise, to have a lot of autonomy and responsibility with no check on what they’re doing … British doctors undergo something called “revalidation” every five years but it’s essentially a paperwork exercise, based on self-reporting.’ Consultants are annually appraised by a colleague in their own department; these appraisals are intended to be supportive, not to raise concerns about poor clinical standards or errors. Part of revalidation involves ensuring that all these appraisals have taken place (there is also a feedback exercise). Revalidation was introduced in 2012 after severe shortcomings were revealed in the oversight of doctors’ fitness to practise, but the BMA, the doctors’ trade union, predicted that it would ‘do very little to weed out underperforming doctors’.

The CQC, I learned later, had been in touch with King’s about Martha’s case in spring 2022. The trust was asked a series of standard questions about its procedures and policies, and that was it. Between October and December that year, the CQC carried out a routine inspection of children and young people’s services at King’s. It’s an open secret in hospitals that when the CQC visits – as with Ofsted in schools – everyone’s on their best behaviour. Some trusts pay for their staff to have training in how to respond to the inspectors’ questions. (‘We all saw what they missed but had to stay quiet,’ one doctor wrote of an inspection on social media.) When I read the resulting report in February 2023, I got the impression that the CQC had just ticked boxes. The report did not take the external review into account: King’s hadn’t shared it with the inspectors in time. The conclusions of the two assessments were strikingly different. The CQC found that poor relations between the liver team and PICU weren’t an obvious problem and that King’s had the issue in hand; its report also concluded that the trust kept detailed documentation of paediatric treatment.

I noticed that, a few weeks before its report on King’s came out, the CQC had prosecuted Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust over the death of Wynter Andrews, who died shortly after birth, and who, along with her mother, Sarah Andrews, had not received ‘safe care and treatment’; the trust pleaded guilty. I asked the CQC what criteria had to be met for criminal prosecution. The answer was evidence not only of ‘provider failure’, as opposed to individual failings, but of a breach of specific regulations. Regarding King’s, I was told that although errors had been made by several clinicians (the CQC seems to accept the idea of individual responsibility), ‘we have not been able to demonstrate a breach of regulation on the part of the provider.’ I reiterated the findings of the external review to the inspection manager and pressed for a fuller explanation of this decision. Progress was painfully slow; I didn’t hear much until the end of July 2023, when I was told that meetings were being held to decide whether to raise the matter with the CQC’s Criminal Cases Assessment Progression Panel.

In September Merope was interviewed on Radio 4’s Today programme, on what would have been Martha’s sixteenth birthday, calling for the introduction of Martha’s Rule. This enables patients, families and staff members to call for a critical care review if they believe a patient’s deterioration isn’t being responded to. (It’s also intended as a cultural intervention, an attempt at flattening hierarchies and giving patients and families more agency.) The idea was quickly taken up by politicians and the press, and thus by an initially reluctant NHS England. (People told us that NHS England, which is about to be dissolved, is often nervous of doctors’ resistance to being told what to do.) Over the next couple of months, executives at the CQC took a closer look at Martha’s case. Their thinking went one way then the other. Finally, in December, I was told that the regulator had decided to open a criminal investigation into the hospital’s failure to provide safe care for Martha. Merope and I gave detailed witness statements, which took several days. After months of delays and havering, there was now some urgency because the Health and Social Care Act 2008 stipulates a three-year cut-off for prosecution from the date an offence is committed.

Accountability at ‘provider level’ began to seem possible. The investigation was to focus on regulations at King’s covering sepsis policy, escalation and the referral pathway to ICU. We were told that some clinicians had refused to co-operate: surprisingly, the CQC does not have the power to compel staff to make a statement. There were further delays when the trust dragged its heels in providing information, but King’s was eventually given legal questions to answer, and the CQC appointed its own clinical expert witness. In May 2024 the expert produced a report a hundred pages long. The trust read and responded to a summary, and details of the investigation were sent to an independent counsel and then a KC for legal review. Nothing was guaranteed, but it looked like the CQC would proceed towards prosecution.

But then the story took a bizarre turn. In mid-August, just before the three-year cut-off, Merope and I were told that the expert witness had decided to withdraw. After many CQC hours and much expenditure, the case was in tatters (the going rate for a clinical expert’s services, the CQC told me, is £500 an hour). In a rush, and knowing that other eligible experts would be reluctant to take on a ‘high-profile’ case, the regulator turned to a less experienced candidate, who produced a report only six pages long. I asked why the main expert withdrew but was told I couldn’t be given that information. My request to see the reports was turned down. I was stonewalled and told nothing, even after an internal review.

So I wrote to the Information Commissioner’s Office, which allows members of the public to ‘request recorded information held by public authorities’, and it ruled in April this year that the CQC was obliged to send me the reports. I turned first to the substantial report, by the first expert; I thought that I couldn’t be affected by reading one more account of Martha’s treatment, but I was wrong. Its conclusions were forthright. King’s escalation policy was not adequate or in line with national standards: ‘It has a glaring failure in that it does not allow the opinion of the ward consultant to be overridden.’ Martha’s ‘deterioration on 29 August was not escalated to PICU because the consultant in charge did not want PICU involvement’. ‘This was an eminently survivable injury and the failings in care’ from midweek ‘led to avoidable harm’. It was ‘not apparent that the staff’ were up to date in the use of various ‘guidelines and tools’, including antimicrobial guidelines. ‘The guidelines that were in place were inappropriate’, and even those ‘were not followed’ on Rays of Sunshine. The substandard treatment began on the Wednesday, when Martha had the DIC. The report highlighted many faults, including the decision not to remove the PICC line. If the correct action had been taken, ‘it is more likely than not that Martha would not have developed refractory septic shock.’ The expert was clear that Martha’s observation numbers (specifically the increase in lactate) showed that she was already in shock at 5 p.m. on Sunday, more than fourteen hours before she was referred to PICU. There were individual and institutional failings, the expert stated: whether the latter were ‘of such a severe degree as to be criminal’ would be a matter for the court. We’ll never know what the verdict would have been (King’s had already denied breaching the regulations), but when the expert withdrew, the trust’s executives were let off the hook. I imagine they were very pleased.

I found out that the expert had withdrawn after seeking, for the second time, legal advice about a potential conflict of interest (in 2022 he had produced a short report about Martha’s treatment ‘on behalf of NHS Resolution’, a body that helps trusts resolve disputes after incidents). His initial legal advice found, as the CQC had, that his authorship of the earlier report did not preclude him from acting as the expert witness. I discovered that King’s, faced with his damning CQC report, had raised the possibility of a conflict of interest. Its intervention paid off. The rushed account produced by the second expert, a consultant and fellow of the Royal College of Anaesthetists, was of astoundingly poor quality. According to the CQC, he also broke procedural rules in compiling it and they did not consider him a ‘credible or reliable’ witness.

I thought back to the CQC’s months of stalling, its flip-flops about whether to go ahead, its initial confidence that King’s didn’t have a case to answer, and wondered how many other hospital failings are ignored. Why had the CQC been so ineffectual and self-protective? The answer seems to be that in 2023 and 2024 it was an institution suffering a nervous breakdown. An independent report found that the regulator’s severe problems included a failure to carry out enough inspections, a lack of clinical expertise among inspectors and inconsistent assessments. The health secretary, Wes Streeting, said it wasn’t ‘fit for purpose’. Its CEO had resigned in June 2024, followed by several of its senior staff. This wasn’t, it turned out, a good moment to pursue accountability at ‘provider level’. The collapse of the investigation was our greatest disappointment in the four-year quest to achieve full recognition of the failings and poor practice at King’s. Having considered its handling of Martha’s case, the CQC drew up the familiar list of ‘learnings’ and improvements.

In February this year Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust was fined £1.67 million after the CQC charged it with six counts of failing to provide safe care to three babies and their mothers in 2021. (It became the first trust to be fined more than once; it had already been fined in connection with the Wynter Andrews case.) One of the babies, Quinn Parker, died a month before Martha. The trust denied making mistakes and refused to share documents with the court; the record of a phone call went missing. Quinn’s parents first complained to the CQC in March 2022, and waited eight months before getting the same response I did: ‘Upon review of evidence we have determined failings at individual level rather than … provider level.’ Nearly a year after first making contact with the CQC, they persuaded it to proceed with a prosecution; in this case, the clinical expert came through. But Quinn’s parents accused the regulator of bungling a separate investigation into the hospital’s failure to follow the duty of candour: the trust can no longer be prosecuted on these grounds because of the three-year statute of limitations. The CQC’s new boss, Julian Hartley, has talked to bereaved families failed by the regulator, and says he wants Streeting to lift the time limit: it takes years for hospital failings to be exposed, particularly when trusts don’t co-operate, and other prosecutors and regulators, such as the police and the Health and Safety Executive, are not subject to the same rule. The reform is badly needed.

Ihad asked the GMC several times for updates into their investigations of the three doctors and provided it with more information. By now I had a new set of questions regarding each doctor’s actions and their reaction to Martha’s death. Why did the Sunday consultant seem so preoccupied with Merope’s anxiety? What led the registrar, before he left the ward, to think that Martha had ‘improved’? And why did the SHO change her explanation for her failure to visit Martha? The Birmingham reviewers, who spoke to her, told us in our meetings that they had found her ‘incredibly defensive. We gave her every opportunity to change her statements to us because they were contradicted by others.’ But the SHO continued to deny that ‘there was anything wrong in the way that, as a doctor, she behaved that night. We thought she’d be in pieces. We are both a little stunned.’ The SHO also told them that she saw her job that night as primarily clerical: it was not her responsibility to ‘review the sick patients’. It’s true that she was the most junior doctor involved, but none of the other resident doctors of a similar grade on the ward shared her perception of their role: ST3 doctors have considerable responsibilities.

Why had the SHO said in her SI statement that ‘no concerns were raised to me through the night shift until approximately 5.50 a.m.’ although the nurse in charge made clear in her SI interview that the SHO had been notified overnight about Martha’s fluid intake, flashes in her vision and tachycardia? (This discrepancy was not mentioned in the SI report.) The nurse in charge was clear that ‘everyone was thinking that Martha was septic.’ Early on Monday morning, when Martha had the cerebral hypoperfusion, why did the SHO wait 75 minutes after her collapse to contact the registrar, doing so only after the results of the usual morning blood gas test came back? Why did she think that Martha had merely fainted, reassuring Merope along these lines, when Martha’s observation chart showed her to be in a critical condition? It was hours after her collapse before Martha was transferred to ICU. During this time she said to Merope in desperation: ‘It feels like it’s unfixable.’