The British Museum was founded in 1753, following the bequest to the nation of Hans Sloane’s remarkable collection, and its development was shaped by the scholarly collectors among its trustees. Of those, perhaps the most significant was Richard Payne Knight (1751-1824), who not only played a role in the museum’s acquisition of Charles Townley’s collection of sculpture and antiquities, but also bequeathed his own collection of Greek coins, ancient bronzes, gems, vases and Old Master and modern drawings to the museum. By doing this, he helped to determine the character of the institution in the early 19th century.

Payne Knight is still somewhat unfairly known as ‘the arrogant connoisseur’, the title of a fine exhibition dedicated to him and his collection held at the Whitworth Art Gallery forty years ago. He was a significant figure in the history of aesthetic theory and criticism, particularly on account of his views on the picturesque and landscape design. He is also known for his interest in the survival and interpretation of the cult of Priapus. Another interest was the origins and development of the Greek alphabet, and he made an important contribution to international debates about the authorship of the Homeric epics.

The Townley and Payne Knight bequests to the British Museum considerably enhanced its collection of Greek and Roman antiquities. Payne Knight’s greatest desire was that the museum would provide the public free access to an unrivalled resource for the study of antiquity and of art. His collection was, first and foremost, a scholarly one, which, in his own words, would serve ‘to gratify taste and curiosity – to please and to instruct’.

The bicentenary of the Payne Knight bequest would have passed unnoticed but for the British Museum’s Department of Prints and Drawings, which has put together an exhibition of drawings from his collection (until 14 September). They display not only Payne Knight’s discernment, but also the range of his collection, which includes light sketches and finished compositional studies, watercolours by his contemporaries, ‘academic’ studies of the nude, and scenes from literature and ancient myth. He also acquired landscape drawings of different periods and schools, from a 16th-century watercolour by Federico Barocci and a 17th-century drawing by the Dutch artist Bartholomeus Breenbergh, to contemporary British artists such as Amelia Long, Paul Sandby and Thomas Gainsborough, a selection of which are on display. His admiration for Claude Lorrain led him to acquire more than 270 of Lorrain’s landscape drawings, seven of which are included in the show.

Of particular interest among the works on display is a drawing of a group of figures dated c.1325-50. Once attributed to Giotto, it is an extremely rare example of early Italian drawing. The chronological scope of Payne Knight’s collection, not to mention the range of genres represented, suggests that it may have been assembled as a comprehensive historical survey. Payne Knight and his fellow collector Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode were among the first in Europe to bequeath their private collections of drawings to a public institution. Both were ahead of their time; subsequent British Museum trustees did not consider drawings a priority until the mid-19th century. That the collection was formed partly with an institutional destination in mind – it was originally intended for the Royal Academy – is made clear by the trouble and expense Payne Knight took to include works by (or supposedly by) Michelangelo. These were not to his taste, but he recognised their importance. The exhibition includes The Holy Family with the Infant St John, the first drawing by Michelangelo to enter the British Museum’s collection.

It is a pity that more is not made of Payne Knight’s other interests and bequests. As the curators of the exhibition point out, the ‘superb quality’ of his collection of drawings ‘transformed the museum’s holdings of works on paper’. The same could also be said of his bequest of Greek coins, and of Greek, Etruscan and Roman bronzes. These parts of his collection are noted only in passing, in a somewhat misleading label which states that ‘Payne Knight’s love of Italy, nurtured over two extended stays there, led to his collecting of Italian art, including ancient Roman bronzes, gems, marbles and coins.’ In fact, Payne Knight was first and foremost a Hellenist, and many of his Roman bronzes and gems were thought to be Greek at the time he acquired them. He specialised in Greek coins (including those from Greek states under Roman occupation, which were known as ‘Greek Imperial’ or ‘Roman Provincial’ coinage), and his collection of them was among the most important formed at the time. Britain lagged behind the Continent in the study of ancient coinage throughout the early modern period, but, in the 19th century, the British Museum became a leading force in numismatics – and by the start of the 20th century was dominant internationally. Payne Knight’s bequest not only helped to establish the museum’s collection of Greek coins, but allowed subsequent curators to access an unrivalled resource for the advancement of numismatics. In addition to providing evidence for the chronological development of the Greek language, coins could also offer valuable insights into the stylistic evolution of ancient Greek art, particularly in its earliest phases where other evidence was lacking.

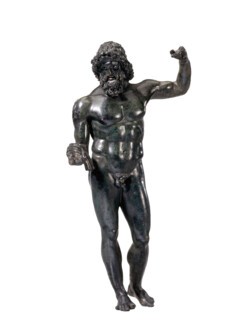

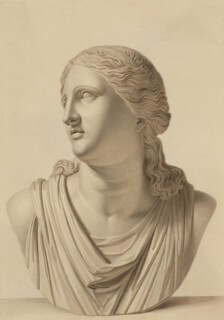

In 1809, Payne Knight published what Nicholas Penny has called ‘the first significant work of art history undertaken in the English language’ in the form of the preliminary essay for the Society of Dilettanti’s Specimens of Antient Sculpture: Aegyptian, Etruscan, Greek and Roman. The exhibition includes a drawing in pen and grey ink by Henry Howard of the marble Head of Niobe, which served as a print study for the illustration in the volume. Payne Knight wrote about the Head of Niobe in the highest terms, but he seems to have had a greater interest in ancient works in bronze. Although such statuettes had been coveted by antiquarians and collectors since at least the Renaissance, they were generally considered to be subordinate to Greco-Roman statues in marble, and Payne Knight’s decision to focus on them was unusual.

The fate of antiquities made of bronze or silver, and found before archaeology became an established discipline, was often the furnace. Great statues were melted down during times of increased demand for weapons and coins and, up until the 18th century, the demand for antiquities by collectors did not prevent many from being recycled for their metal. According to Payne Knight’s records, some of the bronze statuettes from the Paramythia Hoard, discovered in the 1790s, narrowly escaped destruction after being ‘rescued’ by a Greek merchant ‘from the hands of a coppersmith … who had bought them for the value of the metal’. He took them to Russia to be sold to Catherine the Great, who died before the sale was completed. They were instead sold to other collectors. On encountering a stray statuette in the possession of a dragoman working in London for the Turkish ambassador, Payne Knight set out to acquire as many pieces from the hoard as he could. He was eventually able to acquire twelve bronzes, which can now be seen in Room 70 of the British Museum. The whereabouts of the other statuettes mentioned in early accounts of the hoard isn’t known. Room 70 also contains eight Roman silver statuettes found in Mâcon in 1764 and bequeathed to the museum by Payne Knight. These are the only surviving items from the Mâcon Treasure, which was said to have included more than thirty thousand Roman gold and silver coins, as well as jewellery and silverware. The statuettes passed through the hands of several French collectors, antiquarians and dealers, before he reunited them.

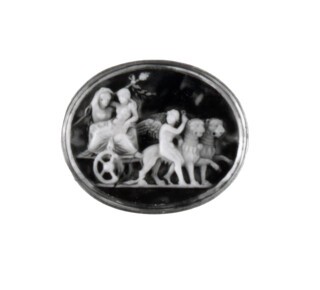

The study of one type of object that Payne Knight avidly collected has been somewhat neglected by the museum: cameos and intaglios (carved and engraved gems). These relics were highly desired by 18th-century collectors, and many scholars, including Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Philipp von Stosch and Pierre-Jean Mariette, considered them fundamental to a greater understanding of the ancient world. Through the work of Mariette, the study of gems was closely associated with the history of connoisseurship. The publications on ancient gems by Stosch in 1724 and Mariette in 1750 were among the best illustrated volumes on art before Payne Knight’s Specimens. With other British Museum trustees, Payne Knight encouraged Taylor Combe to arrange an exhibition of gems in 1814 and gems continued to be an important subject of study well into the late 19th century, not least through the work of Adolf Furtwängler.

Some of the gems that Payne Knight referred to in his writings cannot currently be viewed in the museum, due to the investigations that still continue into the thefts from the collection. Earlier this year, in a piece written by four members of the museum’s Recovery Programme curatorial team, it was revealed that as many as 1200 gems, registered in the early 20th century as having uncertain provenance, have now been identified as belonging to Townley’s collection. Collectors such as Payne Knight were often very careful in the documentation of their own collections and keen to ensure that knowledge of antiquities was widely disseminated. Considerable effort was taken to produce plaster and glass paste impressions of ancient gems and to increase public knowledge of them in the decades before their arrival in the British Museum. Trays of these impressions can be found in the museum’s Enlightenment Gallery, which captures something of the intellectual fervour of these 18th-century inquiries into the origins and development of civilisations.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.