When a man tips his hat on the street, we take it as a friendly greeting. That’s what it means to read visual signs ‘iconographically’, Erwin Panofsky writes in his classic essay ‘Iconography and Iconology: An Introduction to the Study of Renaissance Art’, from 1939 (when men still wore hats and some were friendly). The tipping of the hat, he speculates, began as a chivalric gesture, the removing of the helmet to show that one was unarmed (the handshake might have had a similar long-lost origin). ‘In Panofsky, iconographies are rarely hostile,’ Joseph Leo Koerner notes in Art in a State of Siege, and themes of ‘peaceful accord’ abound in their shared field of Renaissance art, as in the friendship portraits exchanged by humanists such as Erasmus and Thomas More. Panofsky underscored artistic amity for political reasons as well. A German Jew who left for the United States in 1931, he saw art as central to ‘the civilising process’ (to borrow a phrase from Norbert Elias, another German Jew in exile). For Panofsky, Koerner argues, artworks ‘exemplified elective affinities’ and past cultures could be regarded as ‘friends’ too. Moreover, simply ‘by surviving, humanism validated its claim that humanity has a common ground,’ a conviction that ‘faced an enemy’ in Hitler and the Nazis.

Modern aesthetics advanced the cause of amity in other ways as well, by implying that a well-composed artwork encourages a well-composed viewer, that art teaches disinterested contemplation (or ‘sublimation’), and that aesthetic judgment invites us to agree (or at least to agree to disagree) with one another. All this is inscribed in any aesthetic model informed by Kant, and Panofsky was a neo-Kantian, as were influential critics of the postwar period such as Clement Greenberg. For good and bad, these aesthetic assumptions no longer suit our traumatophilic age, and art history has shifted away from Panofsky towards another foundational figure, Aby Warburg, who was drawn to the dark powers of images and to the transmission of passionate expressions over time (he called them Pathosformeln). Warburg often felt besieged – he suffered a nervous breakdown during the First World War, which he saw as the destruction of civilisation – and Koerner feels some of the same pressures in our own time: ‘Today’s greeting gets its iconography from a state of siege.’ Hence one question that animates his brilliant book: ‘What about images that treat their intended viewers as foes, approaching them with bad intent? What happens to meaning in the visual arts when, instead of friendship paintings, we encounter their antithesis: not enemies depicted in painting, not enemies of painting as an art, but enemy paintings as such?’

Koerner first broached this question in Bosch and Bruegel: From Enemy Painting to Everyday Life (2016), and his new book returns to Bosch, whom Panofsky found too alien to appreciate. During his lifetime Bosch was well known as a ‘devil-maker’, a persona he advanced even with his name. ‘Hieronymus’ was a nod to St Jerome, the ascetic translator of the Bible who withdrew ‘from the pleasures of the world only to be besieged by temptations from within’; while ‘Bosch’, which he adopted as his signature, encoded not only his Netherlandish home town, ’s-Hertogenbosch, but also, as Koerner puts it, ‘ideas of sylvan obscurity [bosch means ‘forest’], unruly matter and metaphysical evil’. Bosch painted Jerome a few times. In one image he appears stripped of his cardinal’s robes and prostrate in a gnarly wilderness, with only a crucifix wedged between his arms for cold comfort. As might be expected, Bosch also depicted Jerome severely tested by demons.

In Temptation of Saint Anthony (c.1501), though, the torment isn’t Anthony’s alone; the right panel of the triptych shows a Netherlandish town like ’s-Hertogenbosch stormed by Turkish troops. ‘The demonic siege of the Christian self,’ Koerner comments, ‘thus expands to encompass the entire ecumene.’ It continues in the present, and not only in the perceived Muslim threat to Europe, as Koerner details in a bravura reading of Adoration of the Magi (c.1490-1500). In this ‘decisive scene of amity’, the three kings, Caspar, Melchior and Balthasar, strangers from distant lands and representatives of foreign religions, are welcomed to honour the newborn Christ. Yet the friendly gathering at the stable is crashed by an enigmatic figure, whom Panofsky identified as King Herod but Koerner, citing Lotte Brand Philip, sees as ‘the Jewish Messiah arrived as Antichrist’ already at the Nativity, noting that ‘Christians expected Antichrist to be temporally ubiquitous, circulating through world history.’ That a fiend often lurks behind a friend is a lesson Bosch teaches again and again.

The siege of the Christian self wasn’t only external; it came from within Christendom too. Bosch died in 1516, just a year before Luther is said to have tacked his 95 theses to the church door in Wittenberg. He was working on the cusp of the Reformation, and his devilish depictions of monks, priests and popes could be viewed as anti-clerical. Of course, the Reformation ushered in an age of iconoclasm, with images attacked as idols, indeed as enemies. Bosch ‘therefore played a potentially dangerous game’, Koerner argues in Bosch and Bruegel: not only did he produce paintings of foes but, in a troubling ambiguity, his own pictures could be taken either as idols or as critiques of the same. Most important, he developed a distinctive category of enemy art and weaponised it:

Enemy painting had a purpose beyond simply the depiction of enemies (Satan, devils, heretics, ethnically suspect groups, the alluring world itself), beyond also the perilously playful fashioning of a malignant artistic self. It had a political function as well: that of fostering a wide-ranging but serviceable enmity between a victimised ‘us’ and an aggressively hostile if secretive ‘them’. Nebulous in its identity, but – through Bosch’s pictorial power – visually concrete, this postulated enemy could be conveniently mobilised to arouse enmity toward lesser enemies (e.g. the outsider, the poor, the neighbour), thus befitting viewers of the type documented as Bosch’s chief clientele: powerful overlords seeking to manage forces resisting their rule, often through the imposition in their territories of legal states of exception.

These overlords included Burgundian dukes and Habsburg kings such as Philip the Fair and Philip II, who often laid siege to Netherlandish towns even as they sometimes commissioned Bosch or, later, collected his paintings.

In Bosch and Bruegel Koerner drew on the writings of Carl Schmitt, the Nazi jurist who theorised the state of exception (whereby a sovereign leader suspends the rule of law) and reduced politics to a fundamental opposition between friend and foe. Art in a State of Siege elaborates on this dangerous thought, with the knowledge that Schmitt was obsessed with Bosch, as was Wilhelm Fraenger, an art historian with whom Schmitt corresponded from prison in 1947 as he awaited possible prosecution for war crimes (he was eventually sent home). Fraenger, whose monograph on Bosch is still consulted today, believed he had cracked the code of The Garden of Earthly Delights (c.1500). The triptych shows God with Adam and Eve in Eden on the left panel, and Hell with demonic mutants and devilish doings on the right (where Bosch includes a possible self-portrait). However, interpretation of the central scene – which Koerner calls, oxymoronically yet exactly, a ‘hostile carousel of love’ – is disputed to this day. For Fraenger there was a simple solution: The Garden was not a typical altarpiece but a cult object of a secret sect of Adamites, a group, intermittent since the early Christian period, which held that, since we are made in the image of God, we can regain paradise through our bodies, that is, through sex. Fraenger was wrong – Bosch didn’t know about the sect, which wasn’t active in his time anyway – but, as Koerner admits, this ‘vision of a paradise of lust cannot be unseen’.

Certainly Schmitt couldn’t unsee it, though he turned it on its head. He took Bosch to be a painter of enmity, not love, and understood the prime enemy in The Garden to be ‘the egomaniac’, as figured in the central panel of human commingling: ‘This is nature and natural law, suspension of self-alienation and self-externalisation in a problem-free corporeality: the Adamitic happiness of the garden of earthly delights that Hieronymus Bosch cast in white nakedness upon a panel.’ The idea of paradise on earth was anathema to Catholic conservatives like Schmitt. Such a materialistic understanding of world history overrode the foundational fact of original sin, and such a naive theory of innate virtue was ‘more gruesome than the state of nature in Hobbes’ (reactionary modernists like T.E. Hulme and Wyndham Lewis believed much the same thing). In short, as Koerner ventriloquises Schmitt, ‘the “ridiculous vitality” of carnal desire destroys the principles of matrimony, patriarchy and dominion to which life must be bound.’ As Koerner puts it, what was for Fraenger the ‘Adamic happiness of the garden of earthly delights’ was for Schmitt in 1947 a ‘sinister vision of liberal democracy as an evil machine’. Somehow in his Nuremberg jail Schmitt played the victim.

In Bosch everyone is under siege – a paranoid mentality, pervasive during his time, which he conveyed more vividly than any other artist. ‘On a cosmic level,’ Koerner writes, ‘there was the old foe, Satan, whose rebellion God crushed, seeding the enmity that would bring Eve and Adam low. On a geopolitical level, the enemies could be distant ones, like the Turks or the Hussites, or neighbouring adversaries, like Guelders was to Brabant. Enemies lurked in the hearth and home’ as well. Since Satan and the serpent, then, evil and enmity had been ‘built into the structure’ of things. Even The Hay Wain (c.1512-15), whose central panel is a riotous parade of peasant life, ‘places the world in its everyday unfolding between the beginning in Eden and the end in Hell,’ from which the mighty (a pope, an emperor, a king) are hardly exempt. While Israel is attacked in the Old Testament and Christ is hounded in the New Testament, everybody is threatened by the Last Judgment, and ‘at bottom’, Koerner suggests, ‘the artist’s paintings are all Last Judgments.’ In The Seven Deadly Sins (c.1500), which ‘wraps scenes of vicious humanity around its oculus containing Christ’, the emergency becomes our own. For Koerner this panel, which he deems ‘the most perfect key’ to Bosch, besieges us in the present, too, revealing ‘what, when God turns away in wrath, our end will be’.

Koerner demonstrates how adept Bosch is at the vivid depiction of ‘dangerous moments’, a term that summons yet another Bosch enthusiast and friend of Schmitt: Ernst Jünger. This reactionary militarist-author not only exulted in a modern life given over to technological disruption, but also celebrated the capacity of new media such as high-speed photography and film to capture sudden scenes of disaster and death. This emphasis alerts Koerner to another shift in aesthetic orientation. After the philosopher Gotthold Lessing divided the arts into spatial and temporal categories in Laocoön (1766), it was long thought that, if a static medium like painting were to convey historical or mythological events effectively, it must present the most ‘pregnant’ moment in the narrative. (This imperative continued in abstract painting whenever it was called on to be instantaneous, present to us all at once.) Koerner complicates the neoclassical paradigm of the pregnant moment with Jünger’s notion of the perilous one, pushing it both backwards and forwards in art history: ‘A dangerous Augenblick for dangerous times, Bosch’s art gave form to every viewer’s imagined enemy.’ The Garden of Earthly Delights was designed ‘to act like a time bomb set to detonate in every dangerous here and now’.

Art in a State of Siege is itself a triptych. Along with Bosch, Koerner takes up two other artists attuned to dangerous moments: Max Beckmann, a German painter, damaged psychologically in the First World War, who was a near contemporary of Schmitt and Jünger; and William Kentridge, a white South African shaped by anti-apartheid struggles, and Koerner’s near contemporary. The Bosch chapter, which takes up half the book, comes first; the comparatively brief Beckmann essay serves as a bridge between Bosch, a scholarly subject for Koerner, and Kentridge, to whose work he is personally committed.

The Beckmann chapter examines the Hell portfolio (1919), a series of eleven lithographs that conjures postwar Germany as ‘an infernal city’, replete with maimed veterans, street fighters, prostitutes, politicians, cops and capitalists, all staples of Expressionist and Dadaist art. In his subsequent pictures, where his confrontational style becomes cooler, Beckmann turns to the ‘collective emergency state’ that was the Weimar Republic. This condition wasn’t only psychological; Friedrich Ebert, the Social Democrat who presided over the first six years of the volatile republic, declared no fewer than 136 states of emergency. The Weimar constitution, co-authored by Max Weber, provided for this action through its notorious Article 48, which allowed laws to be suspended ‘if public security and order are seriously endangered’. Hence the definition that Schmitt presented as early as 1922: ‘Sovereign is he who decides on the exception’ – a formula that gave legal cover to the Nazi dictatorship to come.

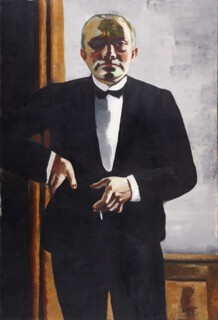

In this tumultuous period, Koerner writes, the belief that ‘the objectified will of one exceptional subjectivity should lead the collective was widespread,’ a claim that permits him to link Beckmann to Schmitt across a great political divide. Here Koerner draws on a manifesto Beckmann wrote in 1927, ‘The Artist and the State’, which treats artistic sovereignty as a model of political sovereignty: ‘The artist, in the new sense of the times, is the conscious shaper of the transcendent idea … It is from him alone that the law of a new culture can emanate.’ As Koerner glosses Beckmann, the Schmittian decider is ‘not a prince, president or dictator, but the artist’. But how sincere is Beckmann here? He painted the artist as a clown as often as a king. At the same time he also specified that ‘the new priest of this new cultural centre must be dressed in dark suits or on state occasions appear in tuxedo,’ and his Self-Portrait in Tuxedo, also from 1927, fits this bill exactly. According to Beckmann, ‘balance’ is the goal in art as well as in government (a notion that Schmitt would scorn), and Koerner argues that Beckmann intended ‘his painted likeness to be the concrete instance of balance achieved’. However, if this is equilibrium it is very fraught, as Koerner demonstrates in one of his many ekphrastic tours de force. The composition hangs on a palette-knife edge between light and shadow, black and white; the opposite of a friendly gentleman tipping his hat on the street, the tuxedoed artist confronts us, glowering, his right hand cocked at his hip, his left nonchalantly holding a burning cigarette. ‘What we have here,’ Beckmann claimed, ‘is a picture of ourselves. Art is the mirror of God embodied by man.’ For Koerner this version of authority challenges us almost as much as the omniscient one presented by Bosch: ‘Like Bosch’s dangerous tableaux that warn, “Beware, God sees,” Beckmann’s Self-Portrait dramatises its sovereign apriority, as it will be looking at you before you glimpse it, and after.’

Yet Koerner also detects a troublesome doubling here: even as Beckmann offered a vision of Germany antipodal to that of the Nazis, he believed, like Goebbels, that ‘a statesman is an artist.’ Might the presumption of sovereignty be the problem, not the solution? The Dadaists thought so; they mocked all authority mercilessly, and their subversive activities made them a target. The Nazis featured the movement prominently in the Degenerate ‘Art’ show in 1937, a chaotic display of avant-garde work staged in Munich (with several subsequent stops) as the despised other of the insipidly neoclassical pieces on view in the Great German Art exhibition across the street. Indeed, for Koerner the Degenerate ‘Art’ show exemplifies the modern use of enemy art, in which ‘the enemy’s own images’ are exposed to enmity. ‘We are going to toss out their old idols on a scale never seen before,’ the curator, Adolf Ziegler, declared, and the Nazis enacted this iconoclasm in full, seizing, selling or stashing (when not simply destroying) avant-garde works of many kinds.

Like Bosch, Beckmann favoured triptychs. Departure (1932-35) was the first of nine that he made; apparently, he liked the way that this once exalted format could only appear degraded, almost weird, in a modern setting. Although, according to Koerner, the painting ‘sustains the myth of artistic sovereignty launched in Self-Portrait in Tuxedo’, the authority depicted in Departure is either out of control or in deep distress, or both. The outer panels present two hellish scenes of torture and murder, with various figures bound, hacked and hung upside down, while the central episode stages the titular departure in the form of a small royal entourage adrift in a boat. The fisher king here is as barren as the one imagined by Eliot a decade before.

Despite the derangement and despair registered in paintings such as Departure and Death (1938), Beckmann appeared to the young Kentridge as ‘a beacon for endangered souls’. Kentridge was born into a Jewish family of anti-apartheid lawyers; his mother was a committed activist, while his father defended Nelson Mandela in his treason trial in 1956-61 and represented Steve Biko’s family at the inquest into his murder in 1977. Eventually, worn down by the regime, the couple went into exile, and Kentridge decided against any direct involvement in law or politics. First he joined a Brechtian theatre group, then studied printmaking. His early prints were process-driven, and he carried over this ‘struggle with materials’ into his drawings in charcoal, which became his signature medium. Kentridge was interested in the way that traces of his images remained on the paper after he erased them, and he exploited this effect when he began to film his drawings; to this day he will make an image, shoot it, alter it, then shoot it again. Koerner takes this obstinacy of traces as a pictorial analogue of the survival of the traumatic past in a South Africa given over first to repression and then to amnesia.

On 12 June 1986 the government of P.W. Botha declared a state of emergency, and a few days later Kentridge gave a talk about ‘art in a state of siege’ that took Beckmann as a model of the artist in such a predicament, who ‘accepts the existence of a compromised society, and yet does not rule out all meaning or value nor pretend these compromises should be ignored’. Just 31 at the time, Kentridge embraced this ambiguous position – in which one is ‘neither active participant nor disinterested observer’, and where ‘optimism is kept in check and nihilism is kept at bay’ – as his own, or rather, the only one available to him. In this brief lecture, which Koerner leans on heavily, Kentridge allows for two other possibilities: art made in a state of ‘grace’ and art produced in a time of ‘hope’. In the former case, art is free to convey ‘immediate pleasure in the sense of well-being in the world’. For Kentridge this aesthetic, which he associates with Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painting, requires a ‘self-confidence’ that he lacks – in his hands such lyricism turns into ‘kitsch or sentiment’. Art made in hope, by contrast, is inspired by times of transformation, if not revolution; his chief example is the Monument to the Third International proposed by the Russian Constructivist Vladimir Tatlin in 1920. In 1986, five years before the repeal of apartheid legislation and the definitive collapse of the Soviet Union, this position was no less ‘inadmissible’ for Kentridge: ‘The failure of those hopes and ideals, their betrayals are too powerful and too numerous. I cannot paint pictures of a future like that and believe in the pictures.’ In his account this left him no alternative but to work out of a siege mentality.

Soon after his talk Kentridge began a silk-screen triptych of three figures representing this ‘three-stage history of art’, as Koerner calls it. A pinstriped tycoon with a ravaged face personifies ‘Siege’; he scowls at us above a cesspool, the image labelled ‘Jhb’ (Johannesburg) and emblazoned with the words ‘100 Years of Easy Living’. A stylish woman in pearls typifies ‘Grace’, apparently undisturbed by the catfish that has somehow landed on top of her head. Finally, ‘Hope’ is signalled by another woman who, her head turned away and further hidden by a mechanical fan, rises above a stadium stand and a large megaphone. Although Kentridge usually presents ‘Siege’ on the left, ‘Grace’ on the right, and ‘Hope’ in the middle, for Koerner each state includes aspects of the others, which suggests that they are less separate stages than dialectically interconnected situations. Clearly, though, ‘siege’ dominated for Kentridge in 1986 as it does for us in 2025. (In another anticipation of the present, the caption to ‘Siege’, which states that ‘cultural activity’, like ‘political activity’, is ‘epistemological struggle’, looks ahead to decolonial thought today.)

‘“Art in a state of siege” is best not pinpointed to a single work, artist or era,’ Koerner submits, and he does move adroitly from Bosch through Beckmann to Kentridge. Art history, he feels, hasn’t done them justice: ‘Beckmann had no place in the advanced art world of the early 1980s – not one of the major modernist art historians ever reflected publicly on his art.’ This is true enough, and it took time for Kentridge to be appreciated too, but Koerner doesn’t reflect on why this was so. In his view, it seems, expressionistic ‘sketches of erotic, violent or morbid subjects’ à la Beckmann and Kentridge are always suited to besieged times. For a historian as exacting as Koerner this is too general an assumption: even in its own period Expressionism became a style of conventional gestures, and by the early 1980s, which saw the rise of Neo-Expressionism, it was little more than a code of recycled clichés. This is one reason Beckmann was overlooked then, and it may have slowed the reception of Kentridge as well. Yet the appreciation did come eventually; if Kentridge began in a state of siege, today he has advanced to a stage of spectacle. Theatrical at root, his talents were eventually tapped for grand productions of The Magic Flute, The Nose and other operas and plays. Siege-become-spectacle: what cultural need does this unlikely mutation serve? What does success of this kind tell us about our moment? Koerner compares Kentridge to Anselm Kiefer, which he means as praise but I take as the opposite: Kiefer doesn’t ‘work through’ history so much as turn it into bombast.

Perhaps Koerner identifies with Kentridge through a shared experience of inherited trauma. (In 2019 Koerner released a moving documentary, The Burning Child, which reflects on the murder of his Viennese grandparents during the Holocaust and the compulsive return of his émigré father to Vienna to paint.) In any case, he is very committed to Kentridge, and while his investment delivers great insight, it also means that he forgoes criticism of the artist and overlooks others who might serve his argument as well or better. Why Beckmann and not, say, Hugo Ball, the Zurich Dadaist who was in close dialogue with Schmitt in the early 1920s, or John Heartfield, the Berlin Dadaist whose photo-text montages directly confronted the Nazis in the early 1930s? Why Kentridge and not, say, Hans Haacke, the Heartfield of our own besieged time, or Thomas Hirschhorn, whose excessive installations mimic emergency as much as Ball’s crazy performances did? Koerner is alert to the question: ‘Countless artworks have been created in extreme states, so why my triptych?’ His answer: ‘Bosch, Beckmann and Kentridge all responded to siege with the “militant irony” particular to satire.’ Yet so do these other artists, if not more so, as some modernist scholars have pointed out, also with emergency in mind.

Koerner makes further provocations: ‘Dates organise this book, not in chronological order, but to capture the synchronicities, ruptures, flashbacks and predictions that – I hope – tell the story of volatile objects that managed to endure. The dates of sieges punctuate history jaggedly.’ Or again: ‘In the extreme state, chronology becomes reversed, collaged and voided. There is Beckmann in Kentridge, Bosch in Beckmann, and Kentridge in Bosch.’ These claims open onto an important debate in recent art history: to what extent is the meaning of an artwork – or a piece of architecture or any made thing – bound up with the circumstances of its creation, its ‘historicity’, and to what extent does its significance develop unevenly over time, ‘anachronically’, in myriad acts of reception? With his jagged punctuation Koerner demonstrates, effectively, that this is not an either/or. We are returned to his initial question: What kind of history might be written about art at times of siege? ‘Histories of art are triumphal,’ he acknowledges, with a nod to Walter Benjamin. ‘Artworks remain with the victors.’ In his view this is far less the case with artists and art historians focused on emergency. ‘Unable to conquer, such art can at most endure’; it suggests ‘a history of the not yet: not yet triumph, not yet lament’.

To his credit Koerner keeps one eye on the present. Certainly, with all the demonic oligarchs and authoritarian leaders strutting the stage today, our world seems both Boschian and Schmittian; we are also inundated with images designed to fuel enmity (immigrants invading ‘our communities’, trans kids invading bathrooms, and so on). Yet though Koerner knows better than anyone how different the eras in his study are, he tends to pull the ancient practice of siege towards the present and push the modern concept of the dangerous moment towards the past, and such historical analogies can conflate as much as illuminate (as the now reflex comparisons of our reactionary moment to the fascisms of the 1920s and 1930s attest). Sometimes, too, he tends to blur the different states of siege, emergency and exception. As Koerner knows, exception is the ‘lawful suspension of the law’, whereas emergency is often illegal; at times, too, the various states are declared by different authorities (sometimes an executive, sometimes a parliament). Per Schmitt, dictatorships diverge too; some are ‘commissarial’ (where the law is suspended only temporarily, at least in principle), while others are ‘sovereign’ (where the law is simply cancelled). Finally, as Koerner notes, the idea of the siege, at least in its modern usage with respect to internal enemies, is ‘the artefact not of absolutist regimes but of revolutionary and democratic ones’. Many admired leaders of the United States, from Lincoln to FDR to Obama, practised the art of exception with relative abandon.

Since the Trojan War ‘sieges have etched themselves into human memory,’ Koerner remarks, but is siege really so hardwired in us? He believes Freud thought so, at least from Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920) onwards, but what follows when siege is treated as a psychological default? Or when emergency is taken as a permanent order? Koerner invokes Benjamin again – ‘the tradition of the oppressed teaches us that “the state of emergency” in which we live is not the exception but the rule’ – but that line was written in 1940, in extremis, and if we repeat it too often, it begins to lose its force: it becomes a general human condition to be suffered rather than a particular political one to be contested. Like ‘siege’ and ‘emergency’, ‘trauma’ can signify too much and too little, connecting different orders of experience, diverse kinds of history, but also, at times, conflating them. ‘Trauma’ is a useful way to mediate the psychological and the social, the personal and the historical, but not if we project the first term in each pair onto the second. In Johannesburg, ‘remembering, repeating and working through past imagery served the dangerous moment, the siege state unfolding then and there,’ Koerner writes of Kentridge, citing Freud’s summary of the task of psychoanalysis. But is the artist an analysand-analyst? For that matter, is the viewer? And are psychological operations truly analogous to pictorial ones? Both are too complicated, too opaque, in their own ways to be readily mapped onto each other.

Obviously, today we live in a schismatic society lacerated with enemy images. In the midst of new battles, though, there are also new alliances, and the reduction of politics to friend versus foe is not only a gift to the right – for this is the way it thinks – but also a misperception of a multipolar world that holds some possibilities along with many perils. In this conjuncture should ‘siege’ continue to rule out ‘hope’? I agree that nihilism must be ‘kept at bay’, but should optimism be ‘kept in check’? Would a little utopianism kill us? The man on the street isn’t always an enemy.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.