In 1345, Ambrogio Lorenzetti painted a monumental mappa mundi for the wall of the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena. At the axis of its rotating concentric wheels was the little city. For painters, Siena was the centre of the world. Dozens and dozens of them lived elbow-to-elbow in a couple of tiny parishes in the commune. They rendered tempera landscapes with pigments cooked from Sienese dirt. The particulars of Sienese daily life are everywhere in the painters’ representations of biblical stories: here are the figured silks worn by Sienese bishops in processions; there are the fashionable tablecloths laid out by the wives of Sienese bankers. When Duccio di Buoninsegna painted the Devil tempting Christ with the kingdoms of the world, he depicted the Devil offering up a miniature model of Siena. Who could have wanted more?

Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-50 (until 22 June) is the first major exhibition of medieval Sienese painting to be held at the National Gallery, having travelled to London from the Metropolitan Museum in New York. It brings together the work of Siena’s four most important painters: Duccio, Simone Martini and the brothers Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Siena was long thought to have been an artistic backwater: ‘It was certainly mean-spirited of the Sienese to persist in being purely medieval right through the Renaissance,’ one critic wrote in 1898. Sienese painters adopted forms so distinct from those of their better-known Florentine neighbours that their work was not always appreciated for its idiosyncratic qualities. There is no single-point perspective, no study of human anatomy, little movement. Instead there is silk, gold and suspended emotion – an embrace of mystery that feels archaic and alien.

The story of European painting hinges on what came before Duccio’s Maestà and what came after. Siena’s governing Council of Nine commissioned the enormous, complex altarpiece for the town’s cathedral; it went from Duccio’s workshop to the Duomo on 9 June 1311 in a great procession, accompanied by the bishop, clergy and the people of the city, along with musicians playing trumpets and kettledrums. It was about five metres high and comprised more than eighty individual painted panels mounted into an architectural frame. Its complexity, its narrative sophistication and its multiple scales and perspectives were unprecedented in the history of altar painting. The front showed the Madonna and Child in a heavenly court of saints and angels; the reverse told the Life of the Virgin and the Life of Christ in 43 distinct panels. The Maestà was sawn apart at the end of the 18th century and the panels dispersed into different collections; this exhibition reunites the surviving eight panels from the back predella of the altarpiece for the first time in 250 years. To see them reassembled is to get a glimpse of what it must have been like to experience the world of Duccio’s imagination in all its intricate drama.

Duccio signed the Maestà with a conspicuous inscription beneath the feet of the Virgin: ‘Holy Mother of God, be thou the cause of peace for Siena and of life for Duccio because he painted thee thus.’ The sheer force of his ambition and vision tormented and provoked Simone, Lippo and Tederigo Memmi, and the Lorenzetti brothers. Duccio challenged them to deepen the emotional intelligence of a face, or to refine the courtliness of a gesture; to reach for new forms of architectural complexity; to emulate gold and marble and silk and clouds and air in tempera.

The painters of 14th-century Siena knew that the virtuosity of their work was a kind of proximity to the divine: they revelled in it just as they worried about its implicit heresy. When Pietro painted a monumental altarpiece for Santa Maria della Pieve in Arezzo in 1320 (recently restored, and on loan for this show), he also signed his work conspicuously: petrus laurentii hanc pinxit dextra senensis. He painted it with his right hand, but ‘dextra’ also called to mind the dextera Dei, God’s hand in creation. At the very top of the altarpiece, floating in the gold space above the head of the Angel Gabriel as he issues the Annunciation, the hand of God emerges from a blue cloud, sending forth the Holy Spirit. Pietro insists – brazenly, but not wrongly – that to paint with his level of skill was nearly divine.

It was a dangerous idea. One revealing and beautiful object in the exhibition is Lando di Pietro’s mostly destroyed sculpted wooden crucifix, made in 1338. Only a few fragments survived the bombing of the Basilica dell’Osservanza in 1944 (Allied aircraft had been aiming for the train station). One is the sorrowful head of Christ: eyes closed in death, cheeks sunken, flesh and curls of hair modelled with incredible care. After the bombing, two scraps of parchment were found inside the sculpture. They contain a prayer by Lando that tells us much about his fraught relationship with God. He carved the cross ‘to recall for people Christ’s Passion’, he wrote. ‘This figure was completed in the likeness of Jesus Christ Crucified, true and living son of God. And one should venerate him and not this wood.’

On his triptych of 1312-15 Duccio inscribed Jacob’s scroll with the words ‘domus dei et porta celi’ – ‘this is the house of God and the gate of Heaven.’ And it was: the proof was in the painting. When Simone travelled from Siena to work at the papal court in Avignon in the 1330s, he met Petrarch, who asked him to paint a portrait of his beloved Laura. Petrarch was so pleased with the painting, which doesn’t survive, that he wrote a sonnet for Simone: ‘But Simone must have been in Paradise … saw her there, and portrayed her in paint/to give us proof here of such loveliness.’ Such work, Petrarch went on, must be ‘conceived in Heaven’, not here on earth, ‘where we have bodies that conceal the soul’.

The Sienese painters experimented with that too – with the problem of what bodies can conceal and reveal. Their way with shaded and mottled gold might suggest an incorporeal Paradise, all diaphanous wings and glinting celestial bodies. But they were serious about the weight and texture of real flesh. There is a lovely fullness to St Anne’s postpartum body as she reclines on a bed in Pietro’s Nativity of the Virgin (1335-42), her rounded thighs and belly gesturing to the physicality of childbearing. In Simone’s tiny Crucifixion of 1340, Christ’s skin has a sickly, unearthly luminosity. And there is all that silk. Draped and folded cloth was a visual idiom the painters used to explore the limits of imitation. The robes and gowns and tunics in the paintings simulate the precious figured silks that would have draped the priestly bodies of the city and the wealthiest women (fragments of these textiles, too, are on display). The silk clings to skin, and gapes from it. The Sienese painters were not ethereal mystics. When they looked into Paradise, they saw the flesh and flash of their own commune.

In 1893 London’s New Gallery mounted the exhibition Early Italian Painting: 1300-50, which included several works of Sienese art. A reviewer for the Standard luxuriated in the high medieval glamour of these paintings and recommended enjoying them ‘sensuously, like a fine day … carelessly sunning yourself in old gold’. But the drama of the National Gallery show – the darkness of the galleries, the arrangement of so many small-scale devotional paintings, the reassembling of long-separated works – makes basking unthinkable. The gold is dense. It’s an energetic presence that thickens the empty dome of Paradise and makes the space between Madonna and Child ripple and quiver. Think of all that textured gilding by candlelight. The distinctiveness of these paintings has been variously explained: the influence of Byzantine icon painting; the force of collective spiritual life in the city; Siena’s communal politics and patronage; its floods of banking money. But the true originality of Sienese painters lay in their ability to make uncertainty material, rendering Christianity’s deepest mysteries in stippled, stamped, glazed and punched gold.

The eccentricities of Sienese life sometimes determined the forms of its painting, and communal political culture created material and artistic challenges for the artists. Simone painted an altarpiece that was designed to be easily disassembled and reassembled, so that it could be moved between the different buildings associated with the governing council of the city, which was re-elected every two months. In Ambrogio’s final work, his Annunciation of 1344, an elegant column spirals from the sculpted arches to the tiled floor, the column not painted but tooled. The words of the Archangel Gabriel are inscribed on the gold, erupting from his mouth in an energetic shot to the Virgin’s breast. The drama of this scene of recognition is not represented on the austere faces of Gabriel and Mary, but in the vibrating space between them. The panel was made not for a church but for the city tax office.

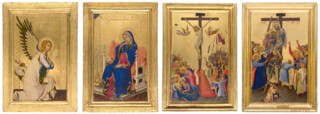

The exhibition closes with Simone’s Orsini Polyptych (c.1326-34), its four painted panels – now held in three different European collections – brought together for the first time in centuries. It is most likely to have been commissioned by Cardinal Napoleone Orsini during Simone’s time in Avignon, and the panels formed a small-scale, private and portable devotional altarpiece. When folded, it would have appeared as a small block of gold and painted marble, the size of a large book. When partially opened, one side depicts the Annunciation, the Virgin reluctant and afraid. And the story does literally unfold: when the polyptych is opened fully, the reverse shows four scenes of Christ’s Passion.

Across the four panels, Simone depicts Mary’s emotional transformation. First, she is collapsed beneath the cross, her body vanished under drapery. Then she stands to receive Christ from the cross, and then she embraces her son’s dead body, supporting his entire weight in her arms. She moves from consuming grief to acceptance, from disembodiment to unnatural strength. Simone’s genius was not just to represent Mary’s awareness of what would happen to her son, but to make his patron, Orsini, an accomplice in that knowledge. The Virgin presses her mouth, her nose, to Christ’s wounded hand, her face in his blood. (Orsini owned a relic of the holy nails that had driven Christ’s flesh into the cross.)

Duccio died in 1318 or 1319, and Simone in 1344. When the Black Death came to Europe in 1348, the Lorenzetti brothers were among its victims. Painting in Siena had been a family business: Duccio had six sons, at least three of whom were painters; Simone had a brother and two brothers-in-law who painted. But there were no more followers after the epidemic. The conversation that Duccio began at the close of the 13th century was silenced by the plague just decades later. Much of the pathos of Sienese painting is due to its intimacy and compression, and also to this fragile sense of historical contingency. Duccio’s tiny Virgin and Child (c.1290-1300) is about the same size as this paper folded in half, and that includes its original frame, with two holes charred by devotional candles. How easily it might have burned entirely. In Sienese painting, the medieval city walls seem to close in. The Virgin and Child are separated from the viewer by a parapet, but Duccio painted it so it seems as though we are looking up at them from beneath the crenellations, almost forcing us to our knees. In his polyptych, Simone makes us part of Mary’s terrible drama. This is what the Sienese painters understood better than anyone. Art isn’t a spectator sport. The Tartar silks that rustle in the paintings stand on the same red-brown patch of dirt that was mixed into tempera. We do not so much look at the paintings as enter into the small but visionary world of their makers.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.