In 1981, in the wake of a budget that slashed government spending amid a steep economic downturn, 364 academic economists signed a letter to the Times. ‘The time has come,’ it said, ‘to reject monetarist policies,’ since ‘there is no basis in economic theory or supporting evidence for the government’s belief that by deflating demand they will bring inflation permanently under control and thereby induce an automatic recovery in output and employment.’ Monetarism held that increases in the money supply cause inflation, and the government argued that cuts to government borrowing were needed to undo that growth. The letter-writers claimed that persisting with deflationary policy would merely ‘deepen the depression’ and ‘erode the industrial base of our economy’. Margaret Thatcher had come to power in 1979 pledging to cut inflation, then at 10 per cent. In 1980 it rose to 18 per cent, with unemployment at 6.8 per cent and manufacturing output contracting by 8.6 per cent. Following the budget announced by the chancellor, Geoffrey Howe, in March 1981, things got worse, not better. The following year, the unemployment rate rose above 10 per cent, where it remained for several years. Nevertheless, Thatcher went on to win elections in 1983 and 1987. Her the-lady’s-not-for-turning episode was an inspiration for Liz Truss during her short and calamitous stay in 10 Downing Street. Truss, unfortunately, wasn’t aware that on the issue of monetarism, the lady was for turning.

It’s not as if nobody noticed at the time. In March 1982, the New York Times wrote that Howe’s subsequent budget – in which the money supply was to be tracked, but not targeted – had ‘in effect buried’ monetarism. But as the Observer journalist William Keegan recognised, Thatcher had ‘invested so much political capital in monetarism’ that she could ‘never admit publicly that it had been wrong’. Tim Lankester, Thatcher’s private secretary for economic affairs for the first two and a half years of her tenure, describes the monetarist experiment as ‘one of the most unsatisfactory episodes of economic policy-making of modern times’. This is civil servant for ‘it was a shitshow.’ His book is mostly a history of policy-making, based on now declassified documents and his own recollections, but also an ‘attempt to achieve some kind of personal resolution’: to ‘come to terms’ with the role he played in the whole sorry saga. He had a ringside view of the decisions Thatcher took, but also a direct connection to their ultimate effects: the small textiles firm run by his wife’s family was one of the many manufacturers, small and large, that didn’t make it out of the 1980s.

Lankester got on well with Thatcher, who generally liked and respected the civil servants working directly under her, despite her suspicion of the public sector and the senior civil service. It was his job to implement the policies of the government of the day, and it ‘did not cross my mind as a middle-ranking civil servant that I could seriously question it’. Not everyone agreed with him. As he briefed journalists on Thatcher’s monetarist policy over dinner in 1981, one of them announced that ‘Tim Lankester is Thatcher’s Albert Speer,’ a phrase that seems to be seared on his memory.

Despite the fact that he was merely a ‘middle-ranking’ civil servant, Lankester was, until January 1981, the only trained economist at Number Ten. He had studied at Cambridge, long a bastion of Keynesianism. The great problem of Keynes’s time was unemployment, at devastating levels in Britain for much of the 1920s and 1930s. For Keynes, this was proof that the economy was not a self-correcting machine: when unemployment was high, governments must use fiscal and monetary policy to increase aggregate demand, kickstarting the deployment of resources lying idle. But Keynes also saw the effects of hyperinflation in Weimar Germany. Far from dismissing inflation, he said there was ‘no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency’. He thought that avoiding excessive inflation had to be a priority for any government; but in a choice between a bit of inflation and a bit of unemployment, he thought it worse ‘to provoke unemployment than to disappoint the rentier’.

In the textbook Lankester used as an undergraduate, the old ‘quantity theory of money’ was described as a ‘blind alley or possibly a red herring’. It was resurrected, however, by Milton Friedman and renamed ‘monetarism’. Inflation, Friedman argued in 1963, was ‘always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon’. If the money supply (M) expanded then each unit of currency would be devalued, and prices (P) would go up. Such were the problems with this theory that the economist Joan Robinson claimed that there was an ‘unearthly, mystical element in Friedman’s thought’. In practice, there were two difficulties, but they were big ones: how to define M, and how to control it. Money is infinitely fungible in theory, but in practice some of it is more high-powered than the rest. ‘High-powered money’, also known as the ‘monetary base’ or ‘M0’, is the narrowest measure of the money supply, encompassing all the cash circulating among the public, plus all the banks’ reserves. There are lots of other measures, too, and the one that was most important in the UK was £M3: this is M0 plus current account deposits plus savings deposits, excluding foreign currency deposits. £M3 is a better indicator than M0 of the actual capacity for spending in the economy. But the government can control M0 by printing more money, whereas it can only influence £M3 via interest rates and government borrowing levels, which nudge people to spend more or save more. As Ian Gilmour, Lord Privy Seal between 1979 and 1981, said, monetarism was ‘the uncontrollable in pursuit of the indefinable’.

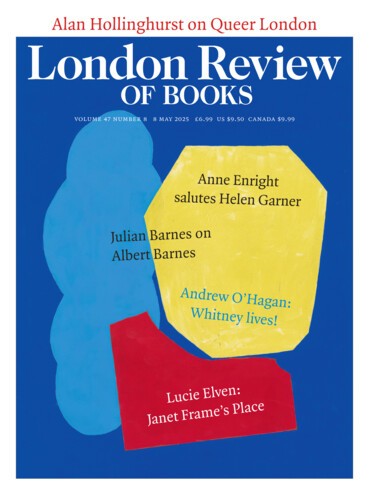

The ‘wets’ within Thatcher’s own party, of whom Gilmour was one, often described her as an ideologue. Gilmour called his book about her Dancing with Dogma (there is a picture of him doing just that on the cover of the LRB of 9 July 1992). For a long time most commentators followed this lead, painting her as the apostle of neoliberalism. More recently, historians have placed less emphasis on her ideological credentials, and have instead seen the Thatcher project as motivated by the drive to power, the day-to-day demands of government and her own home-grown beliefs, rooted in interwar Grantham, where she absorbed the politics of her liberal, Methodist, small-business-owning father long before she ever read Friedman. In this reading, Thatcherism was ad hoc and flexible, not the pure expression of neoliberal theory cooked up in Austria or Chicago. The economic historian Jim Tomlinson argues that Thatcher’s first few years in power represented an episode in ‘adventurism’ rather than the rigorous application of monetarist theory to the British economy. Thatcher and her closest collaborators were simply determined to do something – anything – to upend the economic status quo.

Lankester doesn’t entirely overturn the picture of this early period as ‘adventurist’, but he insists that Thatcher really did believe in monetarist theory. She hated inflation, which she saw as immoral and demoralising: savers must be rewarded for prudence, and governments shouldn’t be able to dodge the consequences of running up large amounts of debt by allowing the real value of that debt to be eroded. She was also convinced by Friedman’s claim that monetarism was a ‘scientific doctrine’ that offered a fail-safe way to curtail inflation – assuming there was the requisite ‘political will’. Thatcher wasn’t dissimulating when in 1980 she ridiculed the idea that she was following ‘some obscure economic religion which demands this unemployment as part of its ritual’: she believed Friedman’s hypothesis that controlling the money supply would bring down inflation with only a very small, temporary impact on unemployment. Unfortunately for her (and especially for the unemployed), this hypothesis proved not to be true.

Thatcher entered government with no clear view on which monetary aggregate should be controlled, or how it could be done. She initially favoured controlling M0, but the Bank of England was opposed, and this route would also have had the unpalatable side effect of taking control of interest rates away from the government. Several years earlier, Labour had begun measuring and then publishing targets for £M3, and there were strong arguments in favour of continuing with this approach, not least the fact that Thatcher and Howe had to introduce a budget within a month of coming to power. So £M3 it was. Labour’s target had been 8-12 per cent annual monetary growth; Howe’s new target was 7-11 per cent. He wanted to send a message to the markets – which are strongly influenced by vibes – but the target was also plainly dictated by political considerations. He could hardly announce a target that was more generous than Labour’s.

The target was totally unmoored from the rest of government policy. To fulfil election pledges to cut government borrowing as well as income tax, the Tories had to increase VAT from 8 to 15 per cent. Thatcher had also promised to accept the proposals of the independent commission on public sector pay, which recommended generous increases. Added into the mix was the increase in oil prices caused by the Iranian revolution. All these factors pushed up prices. High interest rates – required to squeeze the expansion of credit – meant that sterling gained in value against other currencies, boosted by the fact that Britain was now an oil producer; manufacturers producing for export markets found their products were becoming less and less affordable. The government then shot itself in the foot by abolishing exchange controls at the end of 1979, rendering the mechanism for controlling bank lending (and thus M) entirely ineffective. It was now impossible to stop banks from moving into the mortgage market, from which they had previously been excluded. Howe held a meeting in 11 Downing Street at which he implored the banks to hold back. They ignored him – creating the conditions for yet more growth in M and P.

Despite all this, Thatcher doubled down on monetarism in early 1980, announcing a new Medium Term Financial Strategy (MTFS) that set targets for £M3 over the next few years – a bold move, given that the previous year’s target had been missed by a large margin. She began styling herself as a nurse administering nasty but necessary medicine to a mollycoddled patient. Denis Healey, the shadow chancellor, called the MTFS ‘Mrs Thatcher’s Final Solution’. Tidying up the room after a presentation on the strategy by the Treasury’s chief economic adviser to the cabinet in 1980, Lankester found a note from Gilmour to the foreign secretary, Lord Carrington, which read: ‘This is all mad, isn’t it?’ Indeed, it proved impossible to keep £M3 within the range set out in the MTFS (the target for monetary growth was missed in six of the eight years when monetary targets were set). Inflation was not under control. Thatcher convened a series of ‘monetary seminars’ in which, Lankester recalls, she was frustrated by her inability to convince ‘the serried ranks of men’ that her approach was right; tempers ‘frayed’ all round. She blew up at her subordinates: during one outburst, Howe took out his red box and started signing papers while he waited for her to finish. Gordon Richardson, governor of the Bank of England, phoned Lankester to ‘express his despair’ after a particularly bad meeting and – though Lankester was his junior – asked for advice.

Doubters and outright dissenters within the cabinet were growing more vocal and, at a meeting in July 1981, hostility erupted. Everyone present spoke, most of them against the government’s strategy. The minutes record some pretty strong criticisms – for example, that ‘following the recent rioting in a number of cities, the tolerance of society was now stretched near to its limit’ – but Lankester says they ‘fail to capture fully the strength of the opposition’. The lord chancellor, Quintin Hogg, evoked ‘President Hoover’s failure to stop the US economy from being engulfed by the Great Depression’. Howe was unconvincing, Thatcher furious. They were saved by William Whitelaw, Thatcher’s de facto deputy, of whom she reportedly once said: ‘Every prime minister needs a Willie.’ Whitelaw had been a strong contender to succeed Edward Heath as Tory leader, but lost in 1975 to Thatcher. After that, he saw it as his duty to support her. Though Lankester knew from briefing sessions that Whitelaw was a sceptic, he used his political capital to urge patience and unity.

Thatcher admits in her memoirs that she was ‘extremely angry’ during the meeting. Lankester judges that she was ‘badly shaken’, and that her conviction finally began to falter. She did, however, continue to use the rhetoric of monetarism, and Lankester believes she ‘never really lost her obsession with … controlling the money supply’. By the end of 1982 inflation had fallen to 5.4 per cent. This was good news, but also final proof that monetarism didn’t work. Eighteen months earlier, £M3 had been growing at close to 20 per cent; according to monetary theory, inflation in late 1982 should have been 15 percentage points higher than it was. Thatcher’s government, and later John Major’s, experimented with various other methods for containing inflation. In 1988, Thatcher’s second chancellor, Nigel Lawson, proposed making the Bank of England independent and tasking it with keeping down inflation, the path New Labour took when it came to power in 1997.

In the proxy-war-by-memoir that took place between Thatcher and her chancellors in the 1990s, Thatcher described the early monetarist period as a ‘second Battle of Britain’, which she had won. She and her supporters point out that between 1981 and 1989, real GDP growth averaged 3.2 per cent a year. But, as the financial historian Duncan Needham writes, it’s ‘sharp practice’ to look only at growth during the upward bit of the economic cycle. If you look at the whole cycle from 1979 to 1989, you get growth of 2.2 per cent – lower than in the 1970s. In his memoir, Lawson contested his old boss’s account, arguing that the idea of a ‘golden monetarist age’ was a ‘myth’. He was right. The monetarist episode was ignominious – Needham likens it to the Charge of the Light Brigade – but thankfully brief. In 2003, two decades late, Friedman admitted to the Financial Times that ‘the use of quantity of money as a target has not been a success.’

Over Thatcher’s first four years in power, the total economic output was £200 billion less than it would have been if the pre-1979 trend had continued. Thatcher hadn’t intended to destroy Britain’s manufacturing base, but to revitalise it. She wrote in her memoir of her horror that ‘private industry was faltering when we had been saying for years that only successful free enterprise could make a country wealthy.’ But the extremely high dose of deflation she and Howe administered knocked out large numbers of firms – particularly in manufacturing. Once the ‘workshop of the world’, Britain now lags way behind countries like Germany in the proportion of GDP deriving from manufacturing. Deindustrialisation began before Thatcher, and would have happened without her, but its trajectory could have been less harsh. One reason this matters is that industrial jobs tend to have decent pay and conditions, partly because they are easier to unionise; service jobs, by contrast, tend to polarise – they are ‘lousy’ or ‘lovely’ – and promote inequality. Of course, Thatcherites didn’t care all that much about inequality. One of Thatcher’s closest advisers, Alfred Sherman, founding director of the Centre for Policy Studies, wrote in 1977 that inequality created ‘prizes for the aspiring’ and delivered ‘efficiency and justice’. In recent years, however, even researchers connected to such bastions of the Washington consensus as the IMF have started to wonder whether extreme inequality might be creating the conditions for political populism.

Having accidentally destroyed Britain’s manufacturing base, Thatcher pivoted to unleashing the entrepreneurial spirit of the City of London. Luckily for her, the financialisation of the British economy was already well underway: the City had been leading the charge to ‘re-globalise’ finance since the 1960s and, as the historian Aled Davies has shown, was waging a PR campaign to designate its services as vital ‘invisible exports’. This was complemented by another unintended consequence of Thatcher’s monetarist experiment: the end of the system of mortgage lending by a cartel of building societies, which Howe had tried and failed to protect at that meeting in 1979. This system had led to recurrent ‘mortgage famines’ but kept lending costs and house price inflation low, and Thatcher – ideologically committed to home ownership above practically all else – feared the consequences of its demise. She discovered, to her surprise, that the rapid expansion of mortgage credit, and house price inflation, was a solution and not a problem. Those who were able to get on the housing ladder felt rich, and unlocked the equity they had in their homes to fuel a growth in spending. The government was no longer borrowing in order to boost demand in the economy: homeowners were doing it for them. Keynesianism had been privatised.

Thatcher didn’t plan to financialise the British economy; nor did she think she could survive unemployment of more than 10 per cent or rapid house price inflation. By 1990, she’d shown you could do all these things and still win elections. This was the Thatcher transformation. I wouldn’t call it a miracle, though.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.