In 1935, in southern Libya, the German painter Katharina Marr put on desert sandals and a sombrero and climbed a rope ladder hanging off the side of a 15-foot rock. She slipped a thin sheet of paper behind the ropes, held it in place with two of the ladder’s rungs and began to trace a petroglyph. Suspended a few feet to her right, her colleague Elisabeth Pauli did the same. The two women worked as ‘copyists’ for the Research Institute for Culture Morphology, founded by Leo Frobenius, an idiosyncratic German anthropologist and as much of a specialist in African art as anyone was at that time. The rock paintings and etchings they copied during this and other expeditions made their way into the institute’s ethnographic collection. Some were monumental works, thirty feet wide. Others were tiny details, discovered beneath protruding sediment.

Frobenius exhibited works from the expeditions at MoMA in 1937, all done in watercolour, rich in burgundy and black. They showed aurochs and bison, most standing alone; stick-figure humans with horned masks; jumbled hunting scenes including zebras and antelopes; silhouettes of hands alongside the moon; and abstract images constructed with swirls and lines. The public was ecstatic, and Frobenius was all but canonised. But there was barely a mention of Pauli and Marr, or of any of the other copyist-artists – Agnes Schulz, Maria Weyersberg, Elisabeth Mannsfeld – who had prepared a substantial proportion of the rock and cave relevés in the collection. Some of those works are now on view, along with copies and etchings from expeditions led by French scholars between 1920 and 1970, at Prehistomania at the Musée de l’Homme (until 20 May).

Paris has seen a lot of ‘prehistomania’ in recent years. In 2018, the Musée de l’Homme put on a popular Neanderthal exhibition. The following year, at the Centre Pompidou, Prehistory: A Modern Enigma considered 19th and 20th-century artistic responses to the earliest human societies. The Origins of the World, at the Musée d’Orsay in 2021, looked at representations of prehistoric man and his environment between 1700 and the early 1900s.

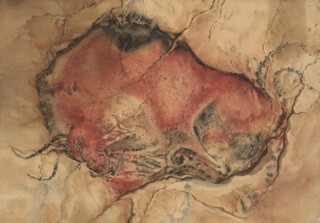

Prehistomania is f0cused on four men, all famous for their ‘discoveries’ and examinations of neolithic sites: Frobenius, and the archae0logists and ethnographers Henri Breuil, Henri Lhote and Gérard Bailloud. But the curators have also posed interesting questions. Since 1963, when it was realised that the respiration of visitors to the cave at Lascaux was causing mould to grow on the paintings, the famous European sites have shut one by one. The non-European sites that remain open are often remote and some have been damaged by attempts to preserve them. We depend now on the photographs and representations that survive in archives and museums. While the best-known petrographs come from a handful of caves on either side of the Pyrenees (Altamira, Lascaux, Chauvet), we learn from the exhibition that at least 45 million prehistoric paintings have been found in more than 160 countries. In Europe, most cave paintings foreground large animals, especially horses, aurochs and bulls, in lush reds and browns. African rock and cave paintings tend to involve congregations of animal and human figures, often traced in contour or painted in stark monochrome red, white or black, almost always in motion. Two particularly beautiful scenes at the Musée de l’Homme capture a semi-human figure towering in size over the others around him; one of these, by Agnes Schulz, features a reclining brown-skinned giant with a horned animal visage and dark clothing in mid-orgasm.

Lhote, the first Westerner to document rock art in the Tassili n’Ajjer plateau in Algeria, emerges as the villain of the show. Among other dodgy practices, he and his crew would repeatedly dampen the rock to make colours stand out, spoiling the paintings. The adventurers featured in the exhibit – Breuil especially – all crafted a prestige for prehistoric art and lived off that prestige themselves. The wall text hints that expedition funding was often politically motivated but, timidly, goes no further. The most contentious issues – the damaging (and in some cases pillaging) of historical artefacts and artworks, and the role played by ethnographers and archaeologists in furthering colonial and capitalist agendas – are left to one side. The curators don’t discuss the fact that Lhote carried out his research with the support of the French government in a remote area of Algeria at a time when France’s repression of the FLN was at its height, or that his reproductions of the cave paintings were used in magazines promoting development and oil extraction, and France’s importance for Algeria. Nor do they tell us that Frobenius served the German Empire in West Africa while amassing his own large personal collection. Still, his work helped inspire two generations of anticolonial intellectuals, from Léopold Sédar Senghor (‘Frobenius has given us back our dignity!’) to Frantz Fanon and Kwame Nkrumah, who saw him as a champion of the originality of African culture.

Breuil, who confirmed the authenticity of the Altamira and Lascaux caves, spent six decades making them famous, and became extremely famous himself. The exhibition pays some credit to his collaborator, Mary Boyle (she is usually dismissed as an ‘assistant’), and notes that Breuil secured funding from the prince of Monaco and, in later years, from diamond mining companies. He wasn’t only an archaeologist but a committed Catholic priest, and he promoted the idea that cave paintings were evidence of a universal religious longing that was to find full expression in Christianity. Some of his interpretations verged on delirium. Confronted with a rock painting at Daureb, in present-day Namibia, he claimed it depicted a Minoan or Egyptian ‘white lady’, painted by a visiting Mediterranean artist, and that the local Khoisan people had later ‘blackened’ other figures at the site. He simply couldn’t conceive that work of such extraordinary quality could have been made by hunter-gatherers in sub-Saharan Africa. Scholars rejected his findings, but Breuil’s patron, Jan Smuts, was delighted.

What are we seeing when we look at representations of cave paintings, rock paintings, petroglyphs, or any parietal art? Are we thinking about anonymous painters from the distant past, or about a monument to them built by 20th-century Europeans? The images were made during a span of roughly 32,000 years and can be found all over the world. It is impossible to know whether they are nearer to art or religion, or whether those terms even make sense in this context. Many seem to encompass the animal, human and divine. In Transfixed by Prehistory (Zone, £30), Maria Stavrinaki writes that the significant role played by prehistoric paintings in fashioning Western notions of modernity – captivating everyone from Picasso to Robert Smithson – means that we can no longer see them clearly. Their sites may have been chosen with care, but we have no sense of their meaning to those early inhabitants.

The earliest interpreters of cave art presented it as shamanic. A caption in the exhibition tells us that Frobenius linked an ‘enigmatic’ scene from the caves at Daureb to contemporary Khoisan beliefs about shamanic journeys. In 1929, when he was writing, it was common to treat Indigenous cultures as static across the centuries. As scholars soon showed, that could not be more wrong. We have no idea what bearing the painting had on the descendants of its creators, if any at all.

Prehistomania encourages viewers to celebrate the variety and mystery of parietal art. But it still can’t separate our aesthetic appreciation of the images from the role they have played in modernity, and very few of us will ever see the originals: the decisions of photographers and copyists, of archaeologists who brightened paintings with water and removed impurities from the cave wall, have all played a part in shaping our perception. To prepare his relevés, Breuil would put a sheet over the originals and copy them in outline, then abstract the copies across several drafts, removing evidence of the wall’s texture and cracks, accentuating stylistic elements. In one of the bison pictures at Altamira, the cave painters had used a bulge in the rock to convey the creature’s massive shoulder. The shape of the wall gave it heft. Breuil’s two-dimensional, abstracted bison does away with this, leaving us to speculate about a symbol rather than a composition. Katharina Marr, who copied the same bison, took pains instead to show the way the original painters had used the surface. In her relevé we can see that the bison’s back and head have been modelled precisely along a jagged wall crack: the shape of the wall is now part of the animal. Marr’s meticulous reconstruction makes the bison feel as though it’s not only breathing with the rock but actively trapped by it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.