Deep beneath the headquarters of the Linnean Society, in Burlington House on Piccadilly, is a bomb-proof room built at the height of the Cold War to protect the collections of the Swedish naturalist Carl von Linné, more commonly known by his Latinised name, Linnaeus. Along with Linnaeus’s books and manuscripts, and his collections of insects and shells, the strongroom houses his herbarium of some fourteen thousand plant specimens, the basis for the Species plantarum of 1753. This is the book that told botanists how to name plants. In his own collection, Linnaeus identified more than four thousand type specimens, each one a distinct physical object to which a specific botanical name was attached. No matter how many revolutions biological classification systems may undergo – and they have undergone several since Linnaeus’s time, from a basis in morphology to phylogeny to cladistics to DNA – the type specimen and the plant name remain bound. The dried plants, each carefully flattened onto a sheet of paper, are botany’s bulwark against a potential Babel of names: different names for the same plant or the same name for different plants, words coming unstuck from things. This is what the Linnean Society strongroom aimed to save from a prospective Third World War: not just the history of botany but its modern foundations in Linnaeus’s legacy.

Gunnar Broberg’s biography of Linnaeus, originally published in Swedish in 2019, is a portrait of the man who, more than any other, has come to epitomise Enlightenment science and even, under the influence of Michel Foucault’s Les Mots et les choses (1966), Enlightenment thinking altogether. Broberg begins with contemporary descriptions of Linnaeus’s person, including Linnaeus’s own itemisation of his most prominent traits: short but muscular build, excellent eyesight, bad teeth, careless about clothes, warts on nose and cheek. The book documents Linnaeus’s life and work, from his youthful travels in Lapland and Western Europe to his voluminous exchanges with some six hundred correspondents and his dealings with his publisher, his university colleagues and students, and his exasperated wife. The wealth of detail is staggering and sometimes suffocating. Do we really need to be told that a casual acquaintance tried to pick up a girl called Doris at a party, or that one of Linnaeus’s students fathered 32 children by three wives? But we should be grateful to Broberg for the decades of research distilled into this volume, the closest thing to a comprehensive and contextualised account of Linnaeus as we are likely to get for at least a generation.

Despite his unflattering self-portrait, Linnaeus wasn’t modest. As a young man he drew up lists of the books he intended to publish, and much later in life, anxious to manage his posthumous reputation, he prepared several vitae of himself that he hoped would serve as material for obituaries. Just in case readers should turn out to be insufficiently appreciative, he wrote reviews and endorsements of his own books. He doesn’t seem to have been a particularly gifted student, graduating eleventh out of seventeen at school and not bothering to sign up for anatomy lessons as a medical student at the University of Uppsala. Yet his self-confidence bordered on the brazen. His particular talent, his one passion, was for natural history, especially insects and plants. He impressed potential patrons, who might otherwise have dismissed him as a brash young nobody, with his prodigious botanical knowledge: in Uppsala, Olof Celsius (uncle of the physicist Anders Celsius); in the Netherlands, George Clifford, a director of the Dutch East India Company and plant fancier; in Paris, the brothers and naturalists Antoine and Bernard de Jussieu. In his journals and letters, he often referred to himself in the third person as ‘the archiater’ (royal physician), an honorary title granted him in 1747 by one of his aristocratic admirers. But the title he really coveted – and wanted engraved on his tombstone – was princeps botanicorum, ‘prince of botanists’.

It was characteristic of Linnaeus to reach for a regal title. Although he wasn’t knighted until 1752 (allowing him the ennobling ‘von’ before his surname), he began issuing taxonomic edicts with the Systema naturae of 1735, which covered the three ‘kingdoms’ of animals, vegetables and minerals. Still more imperious were the Fundamenta botanica (1736), Critica botanica (1737) and Philosophia botanica (1751). As a young man from the scientific periphery, qualified by little more than a quickie medical degree from the Guelders Academy in the Dutch town of Harderwijk, Linnaeus was already fulminating at his fellow botanists. He railed against those who used the notoriously variable trait of colour as a basis for naming plants and who sold sumptuously illustrated books of flowers to wealthy patrons: ‘How many volumes have you written of specific names taken from colour? What tons of copper have you destroyed in making unnecessary plates? What vast sums of money have you fraudulently extracted from other men’s pockets, on the strength of colour alone?’ He rejected plant names derived from resemblances that only an anatomist could recognise. ‘Penis’, yes; ‘Fallopian tubes’, no. As for names that showed off the botanist’s wit and fine style, Linnaeus was scathing. Plant names should be short, simple and transparent; the species name in particular should succinctly capture those features that differentiate the plant from all others in the same genus.

The ideal botanical name was a binomial, composed of the plant’s genus, followed by its species: for example, Acanthus spinosus L., a species of the genus Acanthus differentiated by its spiny leaves. The ‘L.’ is for Linnaeus and signifies that he was the first to publish the plant’s name. Binomial nomenclature was Linnaeus’s innovation and, from the standpoint of contemporary botany, his most lasting contribution. In one of his autobiographical notes for future obituarists, Linnaeus described himself as ‘the greatest reformer of botany’. Louis XV sent him plant specimens he himself had gathered in the royal gardens; Rousseau wrote him a fan letter; Goethe said that Linnaeus’s influence on him was comparable to that of Shakespeare and Spinoza (though probably more as foil than as model). Lady Anne Monson, the British botanist of Indian plants, toasted Linnaeus as ‘king of all the realms of nature’ before raising her glass to George III, who was king merely of Britain and Ireland.

Until his eyesight failed him in old age, he prided himself on being able to recognise hundreds if not thousands of plant species at a glance and on rarely needing a magnifying glass, much less a microscope, to anatomise a plant’s hidden parts. The Systema naturae set out a hierarchical classification system for all naturalia, organic and inorganic. The first edition ran to just twelve pages; the multi-volume twelfth edition of 1766-68 ballooned to 2300 pages. In the tenth edition, from 1758, the ‘Empire of Nature’ is divided into the three kingdoms, and each kingdom is in turn divided into classes, each class into orders, each order into genera, each genus into species, and each species given its unique binomial. Each division into a subordinate category is based on a description of distinguishing traits. In this system of nested categories, human beings, for example, are found in the class of mammals (from the Latin mamma, breasts), the order primates (along with monkeys and lemurs), the genus Homo, and assigned the binomial Homo sapiens. In principle, every species could be assigned a singular place within the Linnaean hierarchy and its own binomial.

As new specimens and observations arrived in Uppsala from correspondents around the world, Linnaeus scrambled to keep his classification scheme from buckling under the weight of all this biodiversity (at some point minerals seem to have fallen by the wayside). To some of his admirers, the Systema naturae seemed to be almost a second creation, and Linnaeus a second Adam: ‘Deus creavit, Linnaeus disposuit’ (‘God created, Linnaeus disposed’). The task of keeping up with nature’s bounty had to be squeezed into the gaps between teaching, administrative duties and replying to letters. ‘All this has crushed my spirit,’ he complained in middle age. ‘Hereafter, I shall sleep until 8 o’clock.’

By the end of his life, Linnaeus had catalogued some twelve thousand species; today there are at least 1.8 million named species, and many more unknown. But what is a species? Since Darwin, biologists have caricatured Linnaeus as the arch-defender of the fixity of species. It is true that in his earlier works Linnaeus stated that God had created a fixed number of species; seeming novelties, such as the striped tulips that had fetched such eye-watering prices on the Dutch market, were varieties bred by cunning gardeners. For Linnaeus, horticulture was one of the dark arts, which fooled less discerning botanists into multiplying species: ‘[Joseph Pitton de] Tournefort enumerates 93 [species of] tulips (where there is only one).’ Yet as he examined more and more species, his conviction apparently wavered. When one of his students found a specimen of ordinary toadflax with an unusual flower, Linnaeus posited that perhaps new species could come about through natural hybridisation. By the 1760s, he had shifted his emphasis from the species to the genus as the stable point in creation and therefore classification. In his revised view, speciation was ongoing: God had combined the orders to create new genera, but thereafter nature mingled the genera to generate new species, at least in the plant kingdom. The immense number of species represented in Linnaeus’s own herbarium must have persuaded him that inventive nature was still hard at work.

The explosion of species previously unknown to Europeans began with voyages of exploration to the Far West and the Far East in the 16th century and accelerated with the commercial and imperial expansion of European powers in the 18th century. The same colonial and commercial outposts in the Americas, Asia and Africa that made possible the first international collaboration in astronomy, with expeditions sent out to observe the transits of Venus in 1761 and 1769, also profited natural history, especially botany (plants were easier to preserve and transport than animals). ‘Profit’ wasn’t just a metaphor in this context. Botany was making the most exciting discoveries, and offered the most lucrative opportunities. New species held out the promise of new medicines, such as the Peruvian bark that cured fevers; new foodstuffs, such as the potato that fed the poor; and new dyes, such as indigo (in an age when textiles still drove global trade). Naturalists made their name through journeys expedited by imperial and mercantile networks: from Carolus Clusius (1526-1609), whose botanising expeditions in Spain and Austria laid the foundations for his botanical garden at the University of Leiden, nursery of the Dutch tulip trade, to Tournefort (1656-1708), who botanised in Greece and the Levant, to the South Seas voyages of Joseph Banks (1743-1820), which enriched Kew Gardens with some thirty thousand new plant species, to Charles Darwin’s round-the-world tour on HMS Beagle.

At the behest of the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala, which was keen on enlarging Swedish territory as well as its collections, Linnaeus had travelled to Lapland as a young man in 1732. But aside from his stay in the Netherlands and visits to Paris and London in the 1730s, that was the end of his foreign travel. He had a terror of sea voyages and took note when a naturalist sent to Suriname in his place died in the field. Instead, Linnaeus sent his students on collecting expeditions to faraway places, carefully instructing them on what and what not to observe: local names for flora and fauna, of course, but also local monuments, wedding and funeral customs, cuisine. Above all, take notes; don’t go to bed until the day’s observations have been written down in proper order. He arranged destinations and found financial backing for his student explorers. By Broberg’s count, as many as a third of them never returned, martyrs to botany and their teacher’s insatiable appetite for new specimens.

In his mature years, Linnaeus explored his native Sweden as if it were an exotic destination, potentially as rich in useful new species as Japan or Peru. This was a decision born of ideology as well as preference. As Broberg reminds us, the Sweden of Linnaeus’s youth had been ravaged by wars lost to an alliance of its neighbours, shorn of its 17th-century Baltic conquests and divided by political factions. Everywhere he went, he found hunger and misery. His domestic botanical surveys were also patriotic projects: to find new food for the starving, new medicines for the suffering, new cash crops for the poor. It would be an understatement to call him a protectionist: he denounced foreign imports (especially French ones) as frivolous luxuries and drains on Sweden’s stores of gold and silver. Rather than enriching itself by global trade, as Britain, the Netherlands, Spain and France were doing at the time, Linnaeus believed that Sweden should strive to make itself an autarchy, growing and manufacturing everything it needed at home. That’s where botany came in. Linnaeus was convinced that by gradually lowering the temperature at which exotic plants such as tea were cultivated in Uppsala’s botanical gardens, he could eventually acclimatise them to Scandinavian conditions. Swedes would one day sip their own homegrown tea and swish about in silk spun from the cocoons of their own silkworms instead of spending their money on expensive foreign goods. When the first tea bushes arrived in Uppsala in 1763, Linnaeus said that he was about to ‘close the gate through which leaves all silver in Europe’.

This was fantasy. Tea didn’t flourish in Uppsala, any more than cultured pearls did in the local river (another of Linnaeus’s projects). Even in his own day and his own country, Linnaeus’s fame rested on his natural history, not his economics. Most famous – and most controversial – was his system for classifying plants based on their reproductive organs, stamens (male) and pistils (female). The Linnaean scheme was branded ‘artificial’ by its critics because, in contrast to ‘natural’ classification systems, it disregarded the morphology of the plant as a whole. The genus Petiveria, for example, which has small white flowers and smells like garlic, belongs to the class Hexandria (plants with six stamens) and the order Tetragynia (four pistils). In principle, all one had to do in order to classify a flowering plant was to count.

The Linnaean system won the hearts of amateur botanists everywhere. Erasmus Darwin exploited the almost pornographic associations in his Loves of Plants (1789), a popularisation of the Linnaean system in anthropomorphised heroic couplets, with the science in the footnotes: ‘Sopha’d on silk, amid her charm-built towers,/Her meads of asphodel, and amaranth bowers,/Where Sleep and Silence guard the soft abodes,/ In sullen apathy PAPAVER [poppy] nods.’ Darwin wasn’t inventing the innuendos; Linnaeus himself saw sex everywhere in nature. Female fireflies were ‘aglow with love’; male and female ants frolicked in ‘leisure and lust’; the snake in the Garden of Eden was ‘treacherous – penis’; Venus reigned ‘over all living things on earth’. To the dismay of more prudish colleagues who disapproved of public displays of female nudity, he went to considerable trouble and expense to have a replica statue of the Venus de’ Medici erected in the garden of the Royal Academy in Uppsala. Amor unit plantas.

Metaphors of family weave through Linnaeus’s career, and not just in the taxonomies of plants and animals. Scholars in many disciplines have long imagined themselves as members of ersatz lineages, recasting teacher-student relationships as bonds between parent and child (and relationships within a student cohort as a form of sibling rivalry). The Mathematics Genealogy Project constructs family trees of academic progeny going back at least as far as the 15th century. In the late Middle Ages, students who achieved the degree of Master of Arts took to calling their professor both ‘mother’ and ‘father’. The terms ‘alma mater’ and ‘Doktor-Vater’ (or, more recently, ‘Doktor-Mutter’) speak for themselves. For early modern botanists, whose project to collect and classify all of the world’s plant species was necessarily trans-generational, professional lineages were particularly meaningful. Since the 16th century, they had constructed genealogies of their predecessors reaching back to Aristotle and Theophrastus.

Linnaeus seems to have invested these substitute family ties with an emotional intensity that went well beyond figures of speech. Broberg estimates that Linnaeus’s household consisted of about twenty people, including his wife, Sara Lisa, their six children and a host of servants, from nanny to milkmaid, not to mention the pet racoon, guinea pig, monkeys and birds. Then there were the many students who visited the house at all hours, ate at the family table, and with whom Linnaeus seems to have enjoyed a warmer relationship than with his eldest son, Carl Junior. Linnaeus covered the walls of his house with portraits of fellow naturalists and named species after them. As in all families, real and ideal, there were tensions: the portrait of Linnaeus’s Swiss rival, Albrecht von Haller, was hung upside down and the name of one of his critics was given to a particularly stinky plant.

One of the effects of Broberg’s panoramic biography is to unsettle earlier interpretations: Linnaeus, the champion of the fixity of species; Linnaeus, the great Swedish scientist and patriot; Linnaeus, the racist and sexist; Linnaeus, the embodiment of the Enlightenment at its best and worst. There is evidence for all of these versions, and Broberg presents it. But his account is too thorough for any single Linnaeus to dominate.

Take the case for Linnaeus, the Enlightenment incarnate. For those who follow Foucault in seeing the Enlightenment as a dream of order achieved by classifying all things on the basis of their visible characters, Linnaeus’s natural history is Exhibit A: at best, order out of chaos; at worst, obsessive compulsion crossed with megalomania. For those who follow the Enlightenment’s own view of itself as a campaign against superstition and error, Linnaeus is also a star witness: he took such satisfaction in having debunked a fake hydra on display in Hamburg that he included it in the elaborate frontispiece to his Hortus Cliffortianus (1737), depicting himself as Apollo trampling the poor beast underfoot. In brisk Euhemerist fashion, he explained away ancient tales of unicorns as narwhals and satyrs as a kind of ape. Was this the triumph of reason, or the disenchantment of the world?

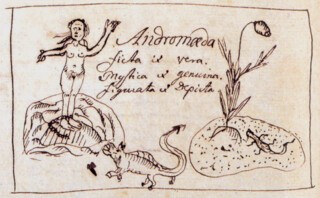

Broberg’s Linnaeus is as capacious as the man himself, who made room for organisms that smeared the boundaries, not only among species and genera but even between kingdoms – the zoophytes, for example, which straddled the line separating plants from animals. He accepted the evidence of the astonishing specimens sent to him from far and wide as well as what the microscope revealed of the life teeming in a drop of water. The same Linnaeus who made short work of hydras and unicorns embroidered his own field notes with fanciful mythological references. To his eyes, bog rosemary (Andromeda polifolia L.) was the very picture of the princess waiting to be rescued by Perseus: ‘The more I thought of her [Andromeda] the more the princess seemed to agree with this herb.’ Next to his drawing of the plant (under attack from a little lizard), he sketched a naked maiden menaced by a dragon. He discounted the barnacle geese of legend but did believe that swallows wintered underwater.

Intellectual historians often settle for describing such apparently contradictory figures as ‘hybrid’ or ‘transitional’, and Broberg does at times suggest that Linnaeus belonged to both the Baroque and the Enlightenment. He certainly had his contradictions. Despite his diatribes against colour, he had the walls of his country house papered with hand-coloured illustrations from Christoph Jacob Trew’s Plantae selectae (1750-73). And he often contravened his own austere instructions on the naming of plants by using a new binomial to make a joke at the expense of an enemy or insert a reference to a story from Ovid. Linnaeus’s personal contradictions do not make him a historical chimera, however. If the man who emerges from this biography sounds odd to those who hold a view of Enlightenment science as rational and orderly, perhaps that’s because real Enlightenment science was a great deal weirder than that.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.