Ilove Balmoral . Not the castle, though it’s fine if you like a bit of crenellated cream puffery. But I love the hills and woods of the Balmoral estate, the restrained charisma of the River Dee as it winds through the farmland of Crathie. The ‘scenery became prettier & prettier’, Queen Victoria wrote on her first trip to Balmoral, ‘& there is much agriculture & cultivation which gives a flourishing look to the country.’ Upper Deeside looks pastoral at first glance, but the bare boulders on the riverbanks speak of flood and force and the episodic violence of meltwater. This is a valley where sudden change is not just possible but inevitable.

I love the Caledonian forest of Ballochbuie, the open invitation of its understorey, the play of light and shadow on the carpet of blaeberry and heather. Some of these Scots pines are older than the House of Windsor, older than the Acts of Union, older even than the House of Hanover. Still, it takes an effort to see beyond the royal presence. There are reminders everywhere, from the well-ordered tracks and ironwork bridges to the luncheon huts and memorial cairns. And there are things unseen. When I was sixteen and conducting research for my Higher geography project on soil acidity, I had to take some samples not far from the ‘widow’s house’, Glas Allt Shiel, on the shores of Loch Muick, which Queen Victoria had built after Prince Albert’s premature death. I was so absorbed with winding the soil augur into the ground, I didn’t at first notice the vegetation moving in front of me. Then I did, and the shock was like stepping on an adder. A clump of heather rose up and stood full height, revealing the figure of a grinning, camouflaged soldier. A platoon of Gurkhas emerged from veils of blaeberry and moss, rifles downwards, to share in the joke. For me, it was an education in the proximate power of the sovereign.

Balmoral seems to transcend its own locality in these moments. Politicians who would not otherwise be interested in a pilgrimage to rural Scotland revere it as a mark of having arrived in other places that matter. The newly elected leader of the Conservative Party, Liz Truss, travelled to Balmoral on 6 September 2022 to be officially appointed prime minister, the 15th that the 96-year-old queen had appointed in her 70-year reign.

Truss packed a lot into her 44-day premiership: the catastrophic budget, the tanking markets, the ministerial resignations and the unwilting lettuce. But it’s the moment of formal installation that sticks in my memory. Photos by Jane Barlow of the Press Association show a frail but smiling queen extending a hand to the prime minister. Another image shows the queen awaiting Truss’s arrival. She stands beside a log fire – supported by her walking stick, handbag over her arm – the focal point in a room of careful symmetry. Everything in the Balmoral drawing room has a corresponding object: a pair of sofas, a pair of lamps, a pair of lamp tables, a pair of vases on the mantlepiece and another on the side tables, pairs of candelabra, cushions and paintings. The notable singularities are the queen and the ormolu clock. Two days later, she was dead.

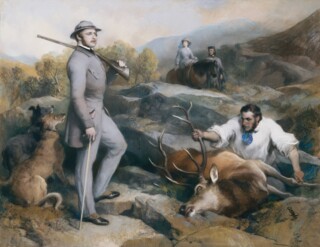

I was captivated by these last photos. At first I thought they were of a 20th and 21st-century figure marooned in a 19th-century setting. Then I realised I had things back to front: it was the aesthetics and social arrangements of the 19th century that were presented as contemporary. The photos were portraits not of the last days of a historical figure but of a continuing and consequential privilege. The paintings on either side of the fireplace, sometimes known as Sunshine and Shadow, were commissioned by Victoria from Edwin Landseer to represent her feelings before and after Albert’s death: happy hunting with him at Balmoral and, ‘as I am now, sad & lonely, seated on my pony’ at Osborne House. In Balmoral in 1860 or Death of the Royal Stag with the Queen Riding up to Congratulate His Royal Highness, Albert is the hero, standing tall after killing a ‘royal’ stag (one with twelve points on its antlers), his rifle slung over his shoulder. From an elevated and distant position the queen looks down approvingly, her loyal ghillie John Brown, leader of the queen’s pony, at her side. John Grant, the head keeper at Balmoral, is on his knees in shirtsleeves, one hand on the stag’s antlers, while the other reaches for his sgian-dubh, with which he will gralloch the beast. The painting on the other side of the fireplace is Queen Victoria at Osborne, a copy of Landseer by Gilbert Sprague (the original is in Osborne House) and, if anything, even gloomier than the original. Here again is John Brown – the faithful Highland ghillie – holding the reins for Victoria, who is sitting side-saddle on a pony, reading a letter (more are scattered on the ground) and dressed in deep mourning.

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes dissected a photograph of a similar scene at Balmoral and decided that Brown represented the punctum of the image: the small detail that ‘pierces the viewer’. Barthes seems not to have known who Brown was, but notes that his symbolic role is to protect her majesty as well as Her Majesty, to protect her voluminous skirts and ‘Victorian nature’. ‘What if the horse suddenly began to rear?’ he asks. We could speculate about the closeness between Brown and Queen Victoria, the stories of the deathbed repentance of the queen’s chaplain Norman Macleod for having secretly married them, or of the queen being buried holding Brown’s photograph, with a lock of his hair, and wearing his mother’s wedding ring. There is no way of knowing the truth of any of this, but the more brazen use of Brown is as a metonym of the loyal Highlander in the wild Highlands. This is the primary work of Landseer’s commissions and it’s hard to overstate their impact in establishing a lasting cultural imaginary of the region.

Another of Landseer’s works makes a similar point, though with less subtlety. Royal Sports on Hill and Loch, his largest royal work, was twenty years in the making, but thought so dreadful that Victoria’s grandson George V had it destroyed (it lives on in various copies and mezzotints). She had laid out her vision for the picture in her journal: ‘the solitude, the sport, and the Highlanders in the water &c. will be, as Landseer says, a beautiful historical exemplification of peaceful times, & of the independent life we lead in the dear Highlands.’ Four servants in kilts hold the boat steady on the shores of Loch Muick, looking up through thick-set brows as the queen disembarks to admire the deer that Albert has again dispatched. Like many Landseers, the painting presents a fixed hierarchy. These pictures show what the Highlands should look like, whom they should belong to, who should do the work, which species are thought to matter and for whose benefit the land should be managed.

It isn’t only the paintings. In the candelabra on the mantlepiece, again the work of Landseer (in collaboration with others), kilted Highlanders hold aloft a clutch of hunting trophies on pikes – stags’ heads, antlers, hunting horns. The Royal Collection Trust says that they ‘exemplify Queen Victoria’s love of all things Scottish’. Victoria and Albert’s thistle wallpaper seems to have gone, but the thistle detail on the fireplace is accompanied by the Latin motto of the vanquished Stuart dynasty, ‘Nemo me impune lacessit,’ translated as ‘No one attacks me with impunity,’ or ‘Wha daur meddle wi’ me?’ ‘I am a Jacobite myself,’ Victoria reportedly told the Windsor Castle librarian. The original tartan carpets have not survived – in Barlow’s picture the carpet is sea green – but the queen wears a Balmoral tartan skirt. Only the royal family and their personal piper are allowed to be clad in Prince Albert’s design (which was intended to resemble Deeside’s rough-hewn granite and not a midprice hotel lobby).

At one level, nothing in the drawing-room scene is surprising. Balmoral has always been a byword for biscuit-tin tartanry. The novelist George Scott-Moncrieff, hardly a radical, described ‘the deadening slime of Balmorality’ as ‘a glutinous compound of hypocrisy, false sentiment, industrialism, ugliness and clammy pseudo-Calvinism’. I admire these descriptors, but I’m not sure that the ‘slime’ scrubs off so easily.

Balmoral is a black hole in the debate over land reform in Scotland. Conversations and policy positions are bent around it. Getting too close to the problem is seen to jeopardise proposals that command widespread support, such as public interest tests for large land sales. Apart from anything else, to talk about Balmoral feels pointed – even rude. Only occasionally has there been a murmur of dissent. In 2007, at the launch of the Scottish political website Bella Caledonia, the land reform campaigner Andy Wightman published an essay called ‘Balmoral Buyout’. His argument was politically a non-starter, but it is entirely correct: ‘any serious attempt at dismantling the concentrated pattern of private landownership in Scotland will get nowhere,’ he wrote, ‘if it does not face up to the fact that the queen’s ownership of Balmoral is a central part of the problem. It remains an obstacle to radical land reform since its continued existence legitimises large-scale private landownership.’

Contrary to popular belief, Balmoral wasn’t owned by the queen. It was originally bought by Albert rather than Victoria to ensure that it did not become part of the Crown Estate, with its revenues surrendered to Parliament. Then Albert inconveniently died. The Crown Private Estates Act 1862 had to be passed to allow Victoria to inherit the estate as part of her personal property, but it stipulated that ownership had to be vested in trustees with the monarch as the beneficiary. A new company, Canup Ltd, was set up in 2005 to act as trustee, with directorships given to two royal family officials (Alan Reid and Michael Stevens) and, most recently, the duke of Buccleuch, Scotland’s second largest private landowner. The Balmoral estate has been valued at £80 million – assets include the 167-room castle, 81 residential properties, commercial forestry plantations, a hydroelectric dam, sporting rights and the tenancies of an A-listed Georgian townhouse in Edinburgh – but Canup doesn’t publish detailed accounts.

This exceptionalism is the essence of Balmorality. There is no need to break the rules because they have been written in such a way that the private interests of the royal family are secured. Such arrangements are indefensible, unfitting and completely normal. When the Scottish Parliament was debating what became the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003– which enshrined a right of responsible access – the bill included an exemption: the legislation shouldn’t apply to the Balmoral estate. An amendment from the independent MSP and former Labour MP Dennis Canavan successfully removed the exemption but not the process that had introduced it: crown consent (in Westminster it’s called king’s consent, not to be confused with royal assent, which is the formal approval of a legislative act). This vetting of the democratic process is intended to ensure that no new legislation affects the crown’s ‘prerogatives’ or its hereditary revenues. Although ministers decide whether such consent is required, it isn’t just a constitutional formality, since the advance notice of forthcoming bills provides an opportunity for lobbying without consent being formally invoked.

An investigation by the Guardian in 2021 found that at least 67 Scottish Parliament bills have been vetted by the monarch over the twenty years since devolution, in order to protect the crown’s ‘private property or personal interests’ (during the reign of the queen, more than a thousand laws were vetted in the UK). This prompted the Scottish Parliament to demand that the government inform it if the monarch has seen a bill before it goes before Parliament. It was reported in October last year that King Charles had been allowed to vet emergency legislation to freeze rents in Scotland as a result of the cost of living crisis. Why? It might affect tenancies at Balmoral.

The ownership and organisation of the Balmoral estate is not the cause of rural Scotland’s problems but it does provide a good example of them: the estate system of landholding and its concentration of ownership; the lack of transparency about who owns what and the use of trusts to thwart public scrutiny; the housing crisis in the Highlands and the unwillingness of any government to tackle second-home ownership; the characterisation of the region as a place of picturesque wildness, a holiday destination, which implicitly classes infrastructure as an anomaly; and the continuing waste and environmental damage from field sports (inhibited woodland regeneration as a result of excessive deer numbers, peatland damage from trampling, the effects of muirburn and so on).

At 18,590 hectares, Balmoral is large, though the Windsors have never found it quite large enough. They added a few more hills and glens in 1947, and again in 1978 and in 1997. Even with these extensions, Balmoral doesn’t make it into the top ten private landholdings in Scotland. It is, however, the country’s best-known estate, an exemplar of the contemporary system of landholding that sprouted, as Marx put it, from the ruins of feudal society: clan chiefs became lairds; clan lands became property; lairds sold to other lairds (or to offshore trusts or institutional investors). Scotland has among the most unequal land distribution in Europe. Wightman calculated in 2013 that half of the country’s privately owned rural land was held by 432 owners. Yet the land problem induces the kind of resignation that’s occasioned by a wet Scottish summer.

This is a bit unfair. The recent struggle for the right to camp on Dartmoor is a reminder that Scots should be glad of the 2003 Act, which, among other things, formalised the traditional right to roam and established a community right to buy. But change in the distribution of ownership has been painfully slow. A report for the Jimmy Reid Foundation by the land reform campaigner Calum MacLeod showed that before devolution and land reform, only 0.7 per cent of Scotland’s rural land was in community ownership. By 2021, the figure had risen to 2.9 per cent – which is hardly the ‘Mugabe-style land grab’ the Daily Mail anticipated in 2003. In Who Owns England? – a nod to Wightman’s 1996 Who Owns Scotland? – Guy Shrubsole found that half of England is owned by less than 1 per cent of its population, around 25,000 people. Around a third, he estimated, is still owned by the aristocracy and the gentry. There are small signs of progress: Labour plans to allow local authorities to share in the so-called ‘planning gain’, the increase in value when permission is granted to develop agricultural land. The Dartmoor National Park Authority and the Open Spaces Society won their appeal against the hedge fund manager and landowner Alexander Darwall for the right to wild camp there.

Most significant is the emergence of the Right to Roam campaign in England that aims to replicate a Scottish-style right of responsible access. In summer 2022, they organised a mass trespass of the Berkshire estate of the rural affairs minister Lord Benyon (he also owns the Glenmazeran estate near Inverness and a substantial part of Hackney), who shelved the Agnew review into opening up countryside access. The Right to Roam is also being refigured as a right to swim. In August, campaigners focused on the River Dart where the Spitchwick estate is trying to prohibit access to waterways in order, it says, ‘to protect the fragile moorland landscape’. And in September the activists Nadia Shaikh and Shafag Elnour joined Shrubsole and Wightman at Scots Dyke on the Anglo-Scottish border to highlight the contradiction that they could have one foot legally placed in Scotland while the foot in England was trespassing. Responsible access is a modest demand, but the forces of landed resistance are formidable. In May, the shadow environment minister, Alex Sobel, pledged to introduce a right to roam in England, only to U-turn in October after pressure from rural landowners. It isn’t easy to redefine the terms of private property in the country that pioneered enclosure. But the fight for access is some way from the fight over redistribution, even if the former carries the unspoken weight of the latter.

Taymouth Castle in Perthshire is a case in point. It was reported in July that Discovery Land Company (DLC), an American real estate corporation, plans to build a 320-hectare gated community for the ultra-rich with Taymouth Castle as its clubhouse. The vast neo-Gothic granite palace was built in the early 19th century by the Campbells of Breadalbane on the site of a 16th-century castle. It was sold in 1921 after the incumbent Campbell incurred large gambling debts, and subsequently used as a hotel, a hospital, a military training centre and a boarding school; when DLC bought it, it had been lying empty since 1982.

DLC don’t just build houses (though 145 are planned for Taymouth), they build ‘worlds’. Everything is laid on. If you can find between $3 million and $50 million for the property in addition to a membership fee, you can arrive by helicopter to enjoy the fine dining, the outdoor pursuits, the wellness and educational facilities – without having to deal with the world the rest of us inhabit. How a gated community might be reconciled with the statutory right to roam isn’t clear, as DLC appears to be finding out. It is still wooing prospective buyers with the idea of ‘private and exclusive sanctuaries’, though a spokesperson recently told MSPs that Taymouth Estate would not, in fact, be a ‘gated community’. Residents of the village of Kenmore, who have seen the closure of their DLC-owned hotel, shop and post office, divide between those concerned about the erosion of access rights and those unwilling to ignore the economic promises such a development might bring.

As ever in these situations, everything orbits around the castle: the hope for new life, the desperation for economic activity, the anxiety that if the development doesn’t go ahead the castle might fall into further disrepair. And then where will we be? The moral jeopardy of ruination is always lurking in the background (though rarely in discussions of social housing). But it is impossible to restore these sorts of building without restoring traces of the social order that produced them. A castle materialises hierarchies. It anchors capital into the landscape and demands economic fealty from its hinterland. The very existence of the castle and the appearance of its power become the justification for maintenance and repair. On the one hand, this returns a familiar order to the landscape; on the other, it’s a reminder that the values of public access and community empowerment were hard-won incursions against precisely this ancien régime. No one buys a castle out of public-spiritedness. A private buyer wants the opportunity to live like a lord. Or a king. That’s the point.

Taymouth has proved particularly controversial, with 150,000 people signing a petition calling for a halt to development. Land is being bought up by different corporate fronts for DLC; there are scores of separate planning applications to Perth and Kinross Council, but no master plan; and, until recently, there was apparent indifference to public access. None of this is ideal. But at least the prospective residents of Taymouth won’t expect British soldiers to act as beaters for their driven grouse shooting, as Prince William did at Balmoral in 2016. Even so, Taymouth shows again that the fundamentals of land ownership and control have been only minimally affected by land reform.

Taymouth Castle is a proto-Balmoral that foreshadowed in taste and sensibility the version of 19th-century landed autocracy that Victoria and Albert propelled to economic dominance, and in which they invested great cultural authority. It was a key stop on Queen Victoria’s ‘little trip’ of 1842 – only the second visit to Scotland by a reigning monarch since the 17th century. To welcome the queen, the marquess of Breadalbane had the place and the people decked out in tartan. This wasn’t an innovation – Walter Scott had stage-managed the pageantry for George IV’s visit to Scotland twenty years earlier – but it had a different flavour here. ‘It seemed as if a great chieftain in olden feudal times was receiving his sovereign,’ Victoria wrote. ‘All was one vast representation of a fairy scene.’ Echoes of this fairy scene are present today in the annual spectacle of kilted Windsors at the Braemar Gathering. Or when the piper to the sovereign wakes King Charles up every morning, continuing the custom of his predecessors all the way back to Victoria, who created the position (Breadalbane had a personal piper and Victoria felt that as queen she jolly well should have one too).

She arrived at Taymouth in the midst of the 1842 general strike, when Chartist demonstrations were at their height. Victoria and Albert’s escape north to acquire Balmoral in 1848 was in some sense exactly that: an escape. Riots in Britain and revolution in France must have made Deeside feel secure by comparison. It’s easy to see why, a few years later, Victoria felt that ‘Scotch air, Scotch people, Scotch hills, Scotch rivers, Scotch woods are all far preferable to those of any other nation.’ ‘My heart is bien gros at going from here,’ she wrote to her uncle, Leopold I of Belgium. ‘I love my peaceful, wild Highlands, the glorious scenery, the dear good people who are much attached to us, and who feel their Einsamkeit [loneliness] sadly very much.’ Landseer, with his ability to paint submissive Highlanders and dead game, was the instrument to turn this private sentiment into a public good.

In September, The Monarch of the Glen took centre stage at the opening of the newly renovated National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh. Since its purchase from the drinks giant Diageo in 2017, it has been trotted around the nation as an ambassador of brand Scotland. A trail of merchandise falls from its haunches: cufflinks, fridge magnets, ties, coasters, lens cloths, greeting cards, silk scarves, tote bags and canvas prints. Curators and critics offer ‘more nuanced’ perspectives on Landseer. The partial rehabilitation of his artistic reputation returns the insignia of Balmorality to the mainstream with symbols of nature and nation that are invariably conservative (The Monarch of the Glen was originally commissioned to hang in the House of Lords refreshment room). By all means marvel at the majesty but, as with Landseer’s lions in Trafalgar Square, the thrill is derived from the spectacle of sovereign violence.

There is still a reluctance to spell out the ecological devastation that two centuries of devotion to red deer have wrought on Scotland. There is minimal recognition that our ecological problems are in some sense art history problems, caught up with what we think Scotland used to look and feel like, and what it should look and feel like. There’s no more prominent symbol of a damaging system of land use and of monopolistic land ownership than The Monarch of the Glen. Yes, the painting is popular in the sense that it has been endlessly reproduced and this makes it a gallery draw. It’s also the antithesis of popular: it marks an expropriation, an estrangement of ordinary people from nature. Deer are to be admired as property, but they are otherwise of no concern to the likes of us.

The imposition of modern property relations on deer outlawed and replaced an older version of hunting as a communal activity. The traditions celebrated by Balmorality are those it legally prohibited for everyone else. The earl of Fife, whose descendants sold the Balmoral estate to Albert, used to seize guns from locals, warning them that they’d be evicted if they gave hospitality to poachers, far less tried it themselves. The Windsors were never this aggressive; they didn’t need to be. They built their fairy-tale castle a few miles east of Tom na h-Eilrig, the hillock of the deer trap, and mimicked the imagined rituals of the old communal order. Prince Harry wrote in Spare of being ‘blooded’ after his first stag kill. A ‘proper old school’ ghillie, Sandy, slit open the animal and ‘pushed my head inside the carcass’:

My breakfast jumped up from my stomach. Oh please oh please do not let me vomit inside a stag carcass … As my face dried, as my stomach settled, I felt swelling pride. I’d been good to that stag, as I’d been taught. One shot, clean through the heart … I’d also been good to Nature. Managing their numbers meant saving the deer population as a whole.

Deer are now more numerous in Scotland than at any time in recorded history. They are everywhere. On postcards. In galleries. In hills and woods and commonly grazing the in-bye of crofts. They’re in gardens, fraying antlers against fruit trees. Or they’re coming through your windscreen (one estimate put deer traffic collisions in Scotland at nine thousand per year). Or hosting tick-borne illnesses such as Lyme disease. Last year, I was one of two thousand or so new cases. I eventually recovered, but not everyone does. There are many reasons for the proliferation of red deer, but it doesn’t help that sporting estates set their own voluntary cull targets in a system that gives every economic incentive to maximise deer abundance yet delivers no sanction if the cull target isn’t met.

Even so, Scotland is now taking a few Bambi steps. October this year saw the legislative removal of the close season on stags, meaning they can now be hunted at any time of the year, something that has upset the British Association for Shooting and Conservation (patron: Princess Anne). An elite field sport may turn into an ordinary form of pest control. And where is the majesty in that? The threat here is to the meaning of deer as well as to their density. In 2009, Douglas MacMillan, a deer expert at the University of Kent, suggested that one solution to the population problem might be to open up deerstalking to a wider range of people, perhaps taking inspiration from Norway, where hunting is commonly undertaken by working-class men. ‘There are a lot of reasons why this would not be practical,’ Charles Fford, laird of the Arran estate, told the Scotsman. ‘You can’t have Rab [C.] Nesbitt types wandering off into the hills to shoot a deer. How would he get it home for a start?’

Conversations about deer management, access rights, natural capital speculation, housing affordability, neglected transport infrastructure, seasonal underemployment, the biodiversity crisis, or any of the challenges that face rural life and livelihoods, always come back to land reform. Politicians from most parties in Scotland may support the idea but achieving decisive change always seems just over the horizon. A steeliness is needed, a recognition that the public interest can only be served by the state intervening in the market. This makes people twitchy. Before the end of the year, the Scottish government intends to introduce a new Land Reform Bill, with public interest tests for large land sales. According to their present proposals, a public interest trigger would be activated in estates over 3000 ha. This would mean an estate like Taymouth could still be sold. The Labour MSP Mercedes Villalba has proposed a Members’ Bill to reduce the threshold to 500 ha. There are plenty of other measures that could be considered: land value taxes, compulsory sale orders for derelict land, or public good tests for landowners who get state subsidies (Balmoral has received £1 million in the last twenty years). The Scottish Land Fund, which has supported the community purchase of 12,000 ha of land since 2016, could also be increased.

If land reform is to unsettle the structures of landholding, it will have to be a cultural movement as well as a legislative endeavour. The question of who owns the land is connected to questions of the way places are characterised, and whose interests these characterisations serve. There is clearly work to do in understanding the rural landscape as a populated space when the opening line on the VisitScotland website is: ‘Scotland is a place of quiet escapes and energising cities.’ Or when ScotRail held a competition in 2021 to name a new fleet of carriages on the West Highland Line and gave the public a choice of Highland Adventurer, Great Escape or (the winner) Highland Explorer. A new spirit of land reform might question why visitors to a place have an assumed primacy over those who live there.

Unpicking the economic order of the estate system will mean unravelling the cultural order of the Victorian Highland myth, with Balmoral as its paradigmatic expression. This sounds like the blast of an old tune, another tilt at the kailyard, or what Tom Nairn called the ‘vast tartan monster’. I’m not sure it has to be. Forty years after Hugh Trevor-Roper’s attack on tartan in a flawed, spiky essay on the invention of Highland tradition, I think we’ve learned to wear it more lightly. Tartanry isn’t the issue here. Land is: who owns it, who benefits from its use and whose histories count.

In 2020, a pair of white-tailed eagles bred for the first time in two hundred years on ‘Royal’ Deeside. The chicks were named Victoria and Albert. It didn’t matter that Queen Victoria was so keen on dead eagles that she commissioned Landseer to paint one, proudly held by the ghillie who shot it, as a present for her husband, or that the eagle chicks were the culmination of a reintroduction effort to combat raptor persecution by gamekeepers on Deeside’s grouse moors. It’s the same old story. The problem is hidden in a tribute to its cause – just another day in the wild Highlands.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.