The Abolitionists in the Park (2020-21), a large oil painting by the American artist Nicole Eisenman, shows a group of figures sitting in City Hall Park in New York. They are part of the 2020 protest to defund the New York Police Department in the wake of the murder of George Floyd. Eisenman herself appears twice in the scene – as a sleeping form on the left of the picture and on the right with her son and daughter. This is a crowded urban fête champêtre, but also a commemoration of a recent event. Like much of Eisenman’s work, it takes as its subject social and political injustice, and the artist’s response to it. Different levels of finish and detail show Eisenman’s compositional skill – this might be the corner of a fresco by Signorelli, or an academic grande machine in the 19th-century Paris Salon. Eisenman says she was thinking of Pieter Bruegel’s Hunters in the Snow (1565), and there are echoes of Bruegel’s macchia, or ‘stains’, in the patches of colour and tone. Bruegel used these macchia to unify his compositions, so that they could be appreciated in one glance. Here the surface patchwork focuses attention on group, rather than individual, identity.

At Eisenman’s Whitechapel show, What Happened (until 14 January), The Abolitionists in the Park (represented by an exhibition copy, or photographic facsimile, as the original was too expensive to ship) hangs opposite the noisy mechanised sculpture Maker’s Muck (2022), in which an ungainly plaster figure is endlessly forming clay on a potter’s wheel to the tinny sound of a transistor radio. The potter is surrounded by studio detritus and small sculptures, from Picassoesque heads to trash assemblages. Tubes of Maker’s Muck, a fake oil paint, are strewn and squeezed across the scene. If the protesters in City Hall Park are doing something significant by sitting still, what of the self-absorbed artist, churning out endless images? As elsewhere in her work, Eisenman figures the work of the artist as shameful – a burdensome and embarrassing narcissism. What is society supposed to do with the sheer accumulation of art, most of it bad? A pack of dynamite wired to a mobile phone in Maker’s Muck suggests one answer, recalling Eisenman’s Self-Portrait with Exploded Whitney, a wall painting made for the Whitney Biennial in 1995. At the centre of a tremendous pile of rubble, from which other (mostly male) artists are trying to escape, Eisenman sits cross-legged, like the potter, calmly painting her bit of wall.

Self-Portrait with Exploded Whitney is one of a number of wall paintings Eisenman made during the 1990s; they recall the Mexican muralists of the early 20th century, and the American artists of the Federal Art Project who took inspiration from them. Paloma’s Minotaure, a temporary wall painting made at the ICA in 1993, showed a grisaille frieze of Amazonian women dispatching male minotaurs. The image was surrounded by painted marble cartouches (Eisenman had previously done trompe l’oeil decoration in Manhattan hotels) with scenes from Picasso. Paloma Picasso’s perfume Minotaure had come out the previous year.

At the same time, Eisenman was making sketches, cartoons and drawings filled with lesbian imagery and characterised by humour and anger towards phallocentric patriarchalism. These are the works that greet visitors to the Whitechapel, standing in for the murals and setting the tone for the exhibition as a whole. ‘Try it. You’ll Like it’ exhorts a sepia ink drawing from 1992, showing a ‘Lesbian Recruitment Booth’ in a retro cartoon style. ‘What to do?’ asks the title of another ink drawing in which an artist sits at an easel, surrounded by a crowd of male figures who stare blankly at her work.

The story of Eisenman’s career as told in the Whitechapel show is one of early success followed by a period of neglect, as the curatorial wheel turned. A painting from 2004 shows a tough-skinned, reptilian figure looking at a letter addressed ‘Dear Obscurity’. Another painting depicts the green-skinned, bowler-hatted figure of ‘commerce’ (based on Eisenman’s art dealer at the time, Leo Koenig) force-feeding the bound and ailing figure of ‘creativity’. This familiar tale was transformed, as for many artists, by a succession of disasters: the war on terror, the financial crisis, Trump’s presidency and the growth of the far right, the climate crisis, the Covid pandemic.

The worse things become, however, the better Eisenman’s paintings get. Coping (2008) shows figures walking silently in a desolate town, up to their waists in a brownish effluent that seems to rain down from clouds of excrement. A mother holds her child (another self-portrait, perhaps) next to an overturned car, half submerged in the flood. But as if to offer absurdity – even hope – a parrot perches on the back of a swimming cat, people continue to drink outside a bar, and, at the centre of the painting, a man in red braces and a bowler hat smokes a cigarette.

Eisenman produces weird imagery with technical expertise, but she doesn’t trade in the off-kilter strangeness, say, of Neo Rauch, and steers clear of Surrealism or the more extreme apocalyptic atmospherics of Daniel Richter. Her concerns are historical, even when she is painting a genre scene. The Drawing Class (2011) shows a dank studio. The model is a smear of pink paint, her features incised in the surface, Art Brut style. Each of the students seems lost in their own imaginings, including a wolfman who holds a stick of charcoal in his painterly paws. Perhaps consciously, Eisenman suggests Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon here – the Catalan brothel becoming a studio in Manhattan. There are even tribal masks on the wall, as if to confirm the comparison. For Eisenman, however, there are no naturalist taboos left to break; instead, her competing styles signal the breakdown of communication in an alien world. And she leaves us in no doubt that even this perspective is localised: the foreground of the picture is taken up with a pair of Guston-like hands holding a sketchbook.

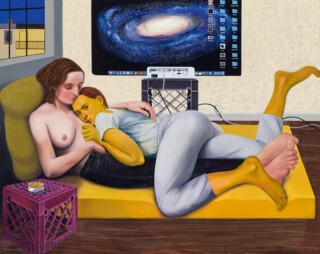

The suggestion of Guston is intriguing. He also began by painting murals, and was in later years fully open to the strangeness and perversion of life. Guston is the direct model for Eisenman’s painting Selfie (2014), in which a large rounded face stares up at a phone screen, reflecting back the protagonist’s single eye. Her 2011 painting Breakup shows a face lost in a screen that once gave pleasure but now is a source of pain. Eisenman captures the anti-aesthetic of screened images, the black hole of gruesomeness they figure in our daily lives. Morning Studio (2016) shows a semi-naked artist lying with her lover on a mattress, the place where an easel would stand occupied by an iMac projecting the Andromeda galaxy screen saver. We scan the desktop for some clue to the artist’s personal life – the top-right folder is labelled ‘Secret Journal’ – but this remains a private realm. Outside the studio window disasters continue to accumulate. Only painting, Eisenman seems to say, can stop the inexorable descent of things: where else can we encounter both rotten life and its utopian counterpoint?

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.