Until March 2022, I’d never seen an episode of RuPaul’s Drag Race, the biggest queer cultural phenomenon in TV history. Even straight friends considered me a pariah. But then I went to stay with a friend who was determined that I lose my Drag Race virginity. Season 14 was midway through; over the course of two evenings, he took me through the first seven episodes, each an hour long.

Back on my own sofa, I returned to Season 1, first broadcast in 2009. I cantered through to the Season 5 finale. Over the next twelve months, I watched all fifteen seasons of US Drag Race, then all fourteen of Untucked, its behind-the-scenes companion show, as well as the seven seasons of All Stars, in which queens who failed to win the series in which they first appeared compete for a second (or even third) shot at the crown. Then I started on the international editions: every episode of Drag Race UK, Canada, Down Under, France, Spain, Italy, Holland, Belgium, Sweden, the Philippines and Thailand – as well as the relevant spin-offs. I dedicated lunch breaks to a couple of seasons of Drag U, the unloved offshoot series in which an everyday cis women is paired with an early Drag Race queen for a makeover. I spent hours watching Drag Race analyses from YouTube creators such as Bussy Queen, Drag Detective, JackFed, GreenGay and the Season 9 contestant Nina Bo’nina Brown. I was supposed to be writing a novel, but as Gia Gunn once said on All Stars: ‘What you wanna do, isn’t necessarily what you’re gonna do.’

If Season 1 had arrived in 2000 I might have watched it from the beginning, alongside Big Brother and Channel 4’s radical queer shows from that period: Eurotrash, Queer as Folk and Metrosexuality (all of which could be relied on for the equal thrills of flaccid dicks and gender non-conforming characters). But in 2009, when that first season aired, I wasn’t watching telly. I had started going out in East London and was encountering the drag scene first-hand. What I witnessed could be glamorously feminine, fashion-forward, scatologically sleazy or inanely poppy (in the form of drunken lip-syncs to Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera songs, where the aim wasn’t to deliver a perfect piece of synchronisation but to make the audience laugh).

It was entertaining, and challenging, but I didn’t understand it. I couldn’t escape the comparison to blackface. The drag scene seemed to me to be dominated by cis white gay men performing stereotypically feminine acts in spaces often devoid of women. Wouldn’t women find drag offensive? Back then the reclamation and redefinition of the term ‘queer’ was in its infancy. Until a friend of mine began transitioning in 2014, I didn’t understand the difference between drag and trans expression.

Part of my delayed engagement with Drag Race may have been down to residual shame, having grown up with Section 28 and as a Jehovah’s Witness. It might also have had something to do with a misguided notion that the show was lowbrow and had nothing to teach me. But I came to see Drag Race as amounting to an archive of evolving social attitudes, even within the queer community itself. Trans contestants were once unwelcome, but now are front and centre (Kylie Sonique Love became the first trans winner on All Stars Season 6). The show has enabled the Polari of drag culture – which itself appropriates the language of Black and Latinx queer communities – to enter the mainstream. It introduced phrases such as ‘it’s giving …’, ‘tea’, ‘she ate that’, ‘sickening’, ‘slay’ and ‘gagging’, which are now ubiquitous among young people, queer or not. ‘RuGirls’ are increasingly in demand in commercial markets. Naomi Smalls, Shea Couleé, Violet Chachki, Gottmik, Symone, Gigi Goode and others walk womenswear runways and are fixtures at the Met Gala and the Oscars. Shangela led the Drag Race ‘Werq the World’ tour. Bianca Del Rio and Bob the Drag Queen sell out solo comedy tours worldwide. Trixie Mattel and Kim Chi have both founded cosmetics brands that rake in millions. Queer people have never been more visible, or more marketable.

Drag Race is a lot of fun. The format is straightforward: between twelve and sixteen queens compete over fourteen weeks; one contestant is eliminated each week until there are three or four left for the ‘live’ finale. We first encounter the queens in the Werk Room – where they dress and do their make-up. One by one, they introduce themselves with a soundbite to the camera before we cut to a ‘confessional’ in which the queen is shown out of drag. Then the presenter, RuPaul, enters the room through the mezzanine door, descends the stairs and welcomes the contestants to the competition, reminding them of the stakes: the queen with the broadest charisma, uniqueness, nerve and talent (or, for acronym lovers, C.U.N.T.) will be awarded a six-figure cash prize and a ‘sickening supply of Anastasia Beverly Hills cosmetics’.

There’s no pretence that drag isn’t painful, time-consuming and expensive. Think Dolly Parton: ‘It costs a lotta money to look this cheap.’ The queens’ bodies are tortured into cartoonishly feminine shapes. Everything is exaggerated: layers of padding around the hips and thighs, tucked genitalia, asphyxiating corsetry, towering heels and large silicone breastplates – not to mention heavy wigs, which affirm the Southern Baptist adage that ‘the higher the hair, the closer you are to God.’ The queens glue down their natural eyebrows or shave them off. They block out any hint of stubble and smooth the foam padding with four or five pairs of tights. Naomi Smalls’s seventy-step make-up routine, distilled into a 33-minute video for Vogue’s YouTube channel, must be at least a three-hour job (fitting her wig, she admits that ‘the goal is to give yourself a headache’). The Season 1 contestant Shannel, a Vegas showgirl, claimed she brought ‘about $25,000 worth of costuming’ to Drag Race, at a time when the prize money was exactly that (for Season 15 it was £200,000).

The structure of each episode is the same: the contestants compete in a mini challenge, a maxi challenge, then take to the runway and are subjected to the judges’ comments. In the season premiere, the mini challenge often takes the form of an absurd photoshoot that tests the queens’ modelling skills – but also their ability to handle fear, discomfort and indignity. It’s essential to be up for anything, to throw yourself in at the deep end. The producers made this literal in Season 5, the first episode of which required the queens to pose for underwater shots in full drag – assisted by a member or two of the Pit Crew, an oiled-up team of perma-grinning gym rats dressed in briefs provided by the show’s underwear sponsor.

A staple mini challenge is ‘Reading Is Fundamental’: to ‘read’ someone is to openly critique them – with maximum wit and minimal cruelty. ‘Reading’ is considered one of the most important skills in drag, along with ‘voguing’, a form of stylised dance originating in Harlem ballroom culture that involves fluently arranging one’s body in a series of poses, as though imitating the models in Vogue. The aim is to impress the audience with the most daring movements – in particular the dip, in which a queen lifts one leg and then arches backwards, dropping to the ground with the other leg bent under her.

The ballroom system, in which queer ‘houses’ – chosen ‘family’ groups, with a nod to high fashion – compete against one another, was established in the late 1960s by Crystal LaBeija, who had tired of the majority-white scene and its discriminatory practices. The first House of LaBeija ball, in 1972, was exclusively for Black queens; the system took off and within a decade there were scores of houses (for a 101 on voguing and the minority ballroom culture Drag Race has commercialised, see the 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning).

The first maxi challenge of a Drag Race season is usually a talent show, which introduces us to the queens, their personalities and skill sets (as well as appearance, queens can be judged on their singing, dancing, posing, lip-syncing, repartee and so on). Backstage, RuPaul asks each of them what they’ll be performing and we learn a little about their backgrounds. In the Season 14 premiere, Willow Pill, a Denver queen born with cystinosis – a genetic disorder that ‘blocks your kidneys and your eyeballs and your fingers … it grows little crystals in your eyes’ – tells RuPaul that she’ll combine a lip-sync with a ‘self-care tutorial’. Her drag, she explains, pits comedy against the difficulty of living with a chronic illness. The walk-through is often an emotional segment – before the lighter mood of the maxi challenge and runway show – and allows the queens to discuss issues such as addiction, their drag and origin families, their careers in and before drag, their experiences of abuse and violence.

Recurring maxi challenges include ‘The Ball’, in which queens model three runway looks, one of which they make from scratch in the Werk Room; ‘Snatch Game’, which involves mimicking queer icons (Cher, Adele, Joan Rivers, but also Melania Trump and ‘Sophia’, the humanoid robot); and ‘The Makeover’, in which the queens give the full drag treatment to a stranger, usually a straight cis man with his own hitherto unasked questions about sexuality and gender identity. There’s also ‘The Rusical’, a musical production that tests the queens’ singing and acting skills. Season 15’s ‘Wigloose’ (based on Footloose) imagined a small town where drag performances have been banned. It was filmed in 2022; earlier this year, such a law was passed in Tennessee.

The show’s mainstay has always been the runway walk. The queens model for the judges and, in a voiceover, describe their drag look and the way they feel wearing it. A queen’s strength lies in her polish, sense of style, taste and charisma. After each contestant has taken a turn on the runway, they assemble on stage and RuPaul announces the first group to go through to the next round – these are neither the strongest nor the weakest performers, but those in the middle. The safe contestants are invited to retire backstage and ‘untuck’ (the inference is that when you’re in drag, your balls are tucked up in their evolutionary cavities and your dick is taped between your arse cheeks). But of course no one loosens their tuck backstage; ‘untuck’ here means to debrief and assess the challenges and the judges’ decisions.

The remaining queens are divided into ‘Tops’ and ‘Bottoms’: the contestants who performed best and worst on the runway. They take their place at the front of the stage. RuPaul calls out one name, then another. These queens have done well and are asked to join the other safe queens. Then she announces the challenge winner – Condragulations! – before the music switches to something more percussive, and RuPaul reads each of the Bottoms in the politest, most deadpan way possible, before almost disdainfully announcing that one of them is safe.

The remaining two Bottoms face off in ‘Lip-sync for Your Life’, the weekly finale, after which one of them will be asked to leave. ‘Good luck,’ RuPaul tells them. ‘And don’t fuck it up.’ There are three kinds of lip-sync track: power ballads, dance numbers (which will have the queens flipping and twirling all over the stage) and the much rarer spoken-word monologue from a camp TV or movie classic. The queens are meant to deliver word-perfect renditions while embodying the soul of the song. To the winner, RuPaul will say: ‘Shantay, you stay.’ To the loser: ‘Sashay, away.’

One of the greatest episodes in Drag Race ‘herstory’ is US Season 5, Episode 7, in which Roxxxy Andrews, a queen who has revealed that her mother abandoned her at a bus stop when she was three, lip-syncs against Alyssa Edwards to Willow Smith’s ‘Whip My Hair’. As the song begins, Roxxxy (who hasn’t done well in performance challenges up until this point) steps out of her skirt to reveal a lace bodysuit. Her wig is (intentionally) brassy and wavy, and one of the judges criticises it for not being big enough. But Roxxxy’s next move is to tuck her thumbs under the wig and remove it to reveal an immaculate, bone-straight blonde wig, which she proceeds to whip back and forth for the rest of the song to everybody’s delight. This might not seem much, but Drag Race queens had been removing their wigs on the main stage for years, revealing nothing but a taped-down cap or their ‘boy hair’, to RuPaul’s distaste (and usually the queen’s elimination). Before RuPaul can make her decision, however, Roxxxy bursts into tears. She explains that the full extent of her mother’s rejection has just hit her in this moment of professional jeopardy. RuPaul launches into a rousing ‘as gay people, we get to choose our families’ speech, then announces an unprecedented tie: ‘Shantay, you both stay.’

Drag Race is a sisterhood, and a masterpiece of queer capitalism. RuPaul, a preppy businessman by day, is a figure of superlative glamour in drag – a Black woman comparable in beauty to Naomi Campbell, Tyra Banks or Iman, strutting down the runway in a gown by Zaldy and a blonde or auburn wig, almost seven feet tall in heels, exuding confidence. She first emerged in the New Wave/genderfuck scenes of early 1980s Manhattan, and has made fifteen studio albums, many of them released to coincide with the start of Drag Race seasons. She is said to earn $50,000 an episode.

I first encountered RuPaul in the early 1990s on America’s Top Ten, a countdown of music videos that aired after the Saturday morning kids’ shows on ITV. One week, the video for ‘Supermodel (You Better Work)’ came on. I was terrified. RuPaul towered head and shoulders above her male dancers and gave off such an obnoxious, condescending energy, while cavorting in a tangerine silk corset and ruffled magenta skirt, that she all but reached in and tickled my ten-year-old Christian gaydom. Watching with my mother and sisters, I felt shame and embarrassment, though it couldn’t have occurred to me, at that age and in my sheltered corner, that RuPaul was a man.

Gender roles have never made much sense to me. The more Drag Race I watched, the more I felt able to break free of them. (I experienced something similar in my twenties, when I became a sex worker as part of an attempt to undo my Jehovah’s Witness mindset.) In bingeing on Drag Race, I was figuring out what it was about myself I wanted to change. Section 28 was repealed in the UK in 2003, the same year I came out as gay. Twenty years later, I have come out again as non-binary. I was named after Pope John Paul II – who was visiting England the week I was born – though my parents switched things round and called me Paul John: the anti-pope. The name never suited me. I’ve decided to drop it, to leave Paul behind. As Michelle Visage, one of the Drag Race judges, might say: ‘Pariah? I hardly know her.’

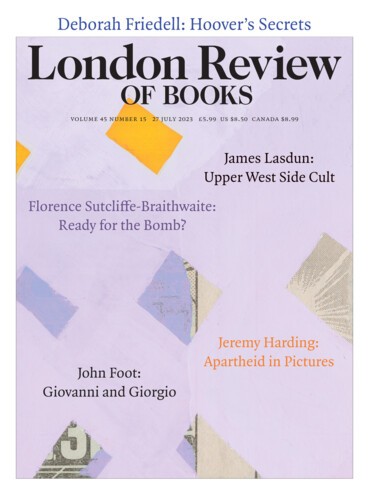

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.