On 16 March 1944, Joseph Beuys’s dive-bomber crash-landed somewhere in the northern steppeland of Crimea. The pilot, Hans Laurinck, was killed immediately. Beuys, then aged 23, was trapped in the wreckage for some time, before being rescued, so he later claimed, by Turco-Muslim Tatars, nomadic herders living in the area between the German and Russian fronts. The Tatars, Beuys said, kept him alive in their yurt by covering him in fat and wrapping him in felt, until he was found by the German army. (Two months after the crash, the Soviet Union began deporting the Tatars across Eurasia to Uzbekistan – retribution for their alleged collaboration with the Germans.)

Beuys had most likely fought alongside Tatars recruited from German prisoner of war camps for the Crimean Tatar Legion; he had also visited Tatar families, perhaps those of fighting comrades, in their yurts, and become familiar with their way of life. But it’s doubtful that his story was true. Official records show that he was admitted to a military hospital the day after the crash, and spent three weeks recovering from his wounds, including facial lacerations, concussion, and probably hypothermia.

Perhaps the story of fat and felt was hallucinated, or a screen memory, alleviating the trauma of the crash. But Beuys seems to have been indifferent to the horrors of war, treating active service, as he once put it, as Bildungserlebnis – an educational experience. He had gone into the war as an enthusiastic young natural scientist who had set up his first experimental laboratory at the age of fifteen; the same year that he took part in the Hitler Youth Sternmarsch to the Nuremberg Rally. Three years earlier he had rescued a copy of Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae from a Nazi book-burning in the grounds of his school in Kleve. During the war he attended lectures at the Reichsuniversität Posen, and found a mentor in Heinz Sielmann, a scientist and aviation instructor at the Luftwaffe school. But Beuys developed a dislike of scientific specialism – a revelation he ascribed to attending a lecture in Poznan by a professor who had devoted his entire career to amoebas. Beuys turned, instead, to the unspecialised realm of art. ‘Science,’ he said, ‘didn’t look to me as if it would have given me the chance to create something stimulating, something that would lead to change.’

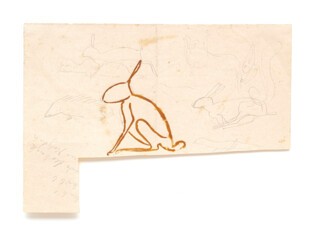

Images of animals appear at the centre of his imaginative life in the postwar years. The sketches of stags and elks he made in 1948 in a small spiral-bound notebook – included in the survey of Beuys’s drawings at the Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery in London (until 22 March) – are made with a typically fine, organic line. One shows two dead stags lying on the ground. Perhaps they had been hunted in the Reichswald in his native Kleve, which in 1948 meant they would probably have been shot by American soldiers, and were therefore symbols of defeat, and perhaps martyrdom. In a series of pencil drawings from the 1950s, Beuys returned to the subject, creating what he called his ‘Stag Monuments’, a motif that occupied him until the end of his life, when it was expressed in one of his last great sculptures, Lightning with Stag in Its Glare (now at Tate Modern).

Drawing was never just drawing: Beuys was already thinking, it seems, in terms of an expanded notion of what art might be; a drawing might show nature, but also itself appear as a fragment of the natural world. To contribute to art, Beuys held, you had to go beyond art. Consider the desiccated leaf of Corylus Avellena (hazel) on which, sometime around 1950, he made a tiny drawing of a bear, the wrinkled veins and serrated margin forming a landscape, as if by synecdoche. Meerengel die Seegurke is a sepia slither isolated on a white sheet, which seems less an attempt to capture the appearance of sea cucumber than to evoke its presence. ‘There’s something about the shape of this animal,’ Beuys said of one of his deer drawings, ‘something different from the surroundings which, in the case of the animal now, is an attempt to describe its inner life and all the forces that are continually at work within it.’

There is an elegance to these early drawings, but also something strange, as if Beuys was creating his own conventions of form and line. They can appear archaic – the work of an eccentric 18th-century zoologist, steeped in a tradition of magical thinking about animals; one that is unashamedly anthropocentric. During the 1960s, Beuys formed a political party for animals, nominating himself supreme leader. For his 1964 performance piece The Chief – Fluxus Chant, he spent nine hours wrapped in a roll of felt, communing with two dead hares: a preparation of sorts for covering his head in honey and gold leaf the following year in How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, a performance at a private art gallery in Düsseldorf, in which he was surrounded by his drawings, many of animals. The instinct and energy of animals could be harnessed for consciousness-raising performances, but the beneficiaries were always humans.

The special status of the human, for Beuys, lay in the capacity to achieve freedom through creativity – thus his famous dictum: ‘Every man is an artist.’ As his drawings show, this was not a matter of technique – he quickly abandoned his natural facility – but rather of making imaginative connections, of forging a symbolic world. The small drawing Ice Age, from 1951, shows the rudimentary forms of four polar bears in a landscape, surrounded by sledges, or what appear to be sledges, carrying beehive-like forms. Other drawings seem closer to Palaeolithic art – his small sketches of stags recall the etched images of deer and other animals found on flattened pebbles at Montastruc. His silhouette images of women, often made with a brown iron-compound based paint known as Beize (German for ‘stain’) bring to mind the reddish-brown Gwion Gwion rock paintings made by Indigenous people in Australia.

Drawings of women were his other recurrent subject at the time (there are virtually no drawings of human males), another echo of the Ice Age image world. These figures are drawn with a nervous, spindly line, isolated on the blank page. They are a sculptor’s drawings: there is little sense of witnessing a scene in space, but rather an intent to identify and characterise form. The 1959 drawing Engländerin (‘English Woman’) echoes the work of Wilhelm Lehmbruck, the only sculptor Beuys recalled being aware of before and during the war. His drawing of a female diver holding a basket-net in one hand and a small snake-like form in the other, could be a Minoan goddess; or a cailleach, a Celtic deer priestess; a sibyl; or a participant in some shamanic ritual. All his drawings of women suggest an affinity with the natural world, and access to a spiritual realm, however vaguely defined. Stranger still are his images of mothers and children, drawn with a sort of mystical tenderness that slides into Beuysian weirdness. Pot Game shows a mother’s legs and arms holding a baby emerging from an impossibly small urn, whose forms echoes the swelling beehives and other vessels that often appear in his drawings.

During this early period, he gathered source material that he would use for his later sculptural work, culminating in the cycle of 350 drawings, made in six notebooks around 1957-60, with the title Joseph Beuys Extends ‘Ulysses’ by Six Further Chapters on Behalf of James Joyce. The notebooks are kept at the Hessisches Landesmuseum in Darmstadt, and have never been published, so it’s difficult to say how exactly Beuys went about his task of augmentation. The obscurity of Joyce’s language must have been part of the attraction. The elliptical and withdrawn nature of the individual drawings – both here and elsewhere – was shored up by their presentation in groups, as a Werkkomplex. A similar idea led him, in the early 1970s, to assemble four hundred of his early drawings to form the single large work called The Secret Block for a Secret Person in Ireland. (It’s difficult not to imagine the secret person being Joyce himself.) Such groupings of work were, he said, ‘like an environment in a drawing character’. He was constantly curating his own work, driven not only by the desire for overview, but also by the care with which fragile things such as drawings, particularly those made on thin onion-skin paper, should be kept: held in place with photocorners, pinned together, glued to a backing, or inscribed and retrospectively dated – not always, perhaps, with the greatest of accuracy.

The drawings he made from the early 1960s, when he became a professor at the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf, have a different character. They are not just imaginative explorations of nature, but often take on a secondary role as plans for sculptural installations and ‘scores’ for his performances and actions. ‘Drawing’ comes to include the blackboards that he made in public lectures and discussions, which alongside the fat and felt became part of the Beuysian aesthetic.

The drawings themselves grew more sculptural, the earthy brown paint Beuys called Braunkreuze brushed thickly on shaped pieces of cardboard, transforming supports into objects with an obdurate, protective quality, much like the grey felt that he used in his sculpture. Rather than some formal exercise in monochrome painting, or an invitation into the infinite à la Yves Klein, the drawings made with Braunkreuze carry allusions to Nazism – to Braunhemd (brown shirts) and the Hakenkreuz (swastika) – though there’s no clear sense of what such associations might mean.

The blackboard drawings are impressive, but lack the introspective quality of Beuys’s drawings on paper. They were not necessarily intended as works of art, and it was only after they were sprayed with fixative by art dealers, sometimes immediately after the lecture or performance had finished, that they were hauled into the realm of (sellable) ‘art’. Looking at them now, without Beuys’s animating presence, one might wonder why there is a horse with three heads inscribed with the word ‘soul’ next to the backwards letters ‘R’ and ‘E’, or a figure holding an apple over his genitals. Pay attention! Beuys’s explanation would probably have been an appeal to the idealistic concepts that dominated his work: his aversion to materialism and scientific positivism, as well as to the Marxist and Freudian interpretations of historical change, neither of which captured what he saw as the role of individual creativity in shaping human history and countering its tragic aspects, particularly environmental degradation.

Two drawings at Thaddaeus Ropac relate to Beuys’s project 7000 Eichen (7000 Oaks), one of the most prophetic public art projects of the 20th century. Invited to participate in the Documenta exhibition at Kassel, Beuys refused to show sculpture inside the museum and proposed instead to plant seven thousand trees in and around the city, each accompanied by a column of basalt, a project that lasted from 1982 to 1987. The drawings relating to 7000 Eichen appear like relics of the action, giving little clue as to what was involved: one carries a list (not in Beuys’s hand) of obscure names; another has sketches of cars inscribed with ‘FIU’ (for the Free International University, which Beuys founded with Heinrich Böll and others), two dried plants and the words ‘thirteen shovels’. It’s debatable whether these are drawings at all; they are certainly of a different order of obscurity to the earlier drawings of animals and women. But the same might be said of his ‘drawings’ of leaves, the earliest of which dates from the late 1940s, and which consist of nothing more than a leaf attached to a piece of paper or card. What are we looking at? Here he seems like a Ruskinian incarnation of Duchamp, transforming fragments of nature into ready-mades.

Two years after Beuys’s death in 1988, the art historian Lynne Cooke wrote of the ‘decisive playing down of his radical thinking about social change’ as the price of his work began to increase. And yet it doesn’t seem strange to be looking at Beuys’s drawings in the elegant galleries and corridors of Ely House, where the Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery is based. Not because Beuys failed in his project, but because his vision of art and the shaping power of individual creativity have lost none of their urgency.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.