Swami Vivekananda might never have become a guru to the world if he hadn’t met a stranger on a train. In the summer of 1893, he travelled from India to represent Hinduism at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago, only to discover that he had arrived several months early. Not having budgeted for such a long stay, and bereft of other ideas, he remembered Kate Sanborn, an intellectual Yankee he had met on the train ride from Vancouver. He looked Sanborn up in Massachusetts, and soon became friendly with other Boston Brahmins who had long associated the East with enlightenment. By the time he wowed Chicago with the tolerance and intellectual suppleness of Hinduism, he had already begun to establish the mainly female network that would fund his missionary work back home. Today, he is remembered by Indians as a manly pioneer of Hindu nationalism, who advised his followers to eat meat and bulk up their biceps. In the West, he is known, if at all, in equally essentialist terms, as the Oriental mystic who taught Americans to do yoga. Ruth Harris, who confesses that she has never taken to yoga, argues that both representations miss the point. Vivekananda might have styled himself as an avatar of timeless Eastern wisdom, but he was a creature of steam trains and ocean liners. In the years between his appearance in Chicago and his early death in 1902, he became the face of a quintessentially modern – because newly global – form of religiosity.

Harris’s sprawling biography lucidly explores the moment when religious figures became conscious of themselves as global actors. In books on the history of Lourdes and the Dreyfus Affair, she revealed the spiritual dynamism of fin-de-siècle Europe. Her focus here isn’t the strange new articulations of Christianity arising from contests between French ultramontanes and their enemies, but an inchoate and infinitely more expansive form of spiritual modernisation. Vivekananda appealed to a loose coalition of Anglophone Protestants who were looking for a successor religion to Christianity, a universal faith that might be capable of inaugurating an ‘age of global idealism’. This new faith would offer intellectual reassurance to homeless Christians, as well as contradicting the racist and materialistic ontologies of empire. Yet in mediating between India and the West, Vivekananda and his friends were often misunderstood in both spheres.

Vivekananda was born Narendranath Datta in 1863 in Calcutta. The city was an excellent place to train as a global guru. Its indigenous elites had long struggled to reconcile local spiritualities with the cultural and commercial possibilities created by Calcutta’s status as the administrative capital of the Raj. Harris combs the hagiographical literature on Datta’s early years for clues about the progress of his inner life. His family, which belonged to the courtly Kayastha caste, had hoped to insert him into imperial power structures. They sent him to a Presbyterian school, whose Scottish teachers helped him become fluent in English and familiar with the Bible. Afterwards, like many ambitious young men, he joined the Brahmo Samaj movement. Its leaders followed the example of the revered Ram Mohun Roy in seeking to free the Brahmin elite from the trammels of caste observance. They claimed to have found in the Vedas an ancient monotheism that fused the human spirit with the creator Brahma, and imagined India as the seat of a great civilisation and a tolerant, universal religion that combined Hindu and Muslim features. They also supported demands for greater Indian self-government.

Brahmoism was a fractious movement, but it agreed on viewing Bengal’s traditional form of religion as priestly fussiness. Brahmos equated what was becoming known in the 19th century as Hinduism with an idealised upper-caste family life, which caught the fancy of domestically minded British Protestants. Roy was staying with some Bristol Unitarians when he died of meningitis in 1833 (he was buried at Arnos Vale Cemetery). Keshub Chunder Sen, his most prominent successor, flirted at length with Unitarianism. He was also a sentimental monarchist who treasured his audience with Queen Victoria during a tour of England in 1870. Although Brahmoism was meant to provide a platform for Indian self-government, it seemed instead to be training a tame clerisy, who worked for rather than with the British.

Datta’s British education seems to have generated its own spiritual antidote. One of his teachers, trying to explain what Wordsworth meant when he spoke of ‘trances’, is said to have referred him to Ramakrishna, a yogi at a nearby temple. In fact, curiosity about Ramakrishna was already widespread by the time of their first encounter in 1881. Even if the story is untrue, it captures Ramakrishna’s allure as a romantic rebel. A distinctively unworldly Brahmin, he had followed his brother to Dakshineswar, a complex of temples devoted to Kali and Krishna. His brother then died, triggering a crisis in Ramakrishna, which he resolved by behaving in ways that deliberately violated his caste position. He cleaned latrines, touched excrement with his tongue and urinated from a tree while impersonating the monkey god Hanuman. These gestures were demonstrations of his absorption in Vaishnavism, a form of ecstatic piety practised in Bengal. He brooded on the gods until his pores sweated blood. He masqueraded as Krishna’s consort Radha, putting on a wig and visualising himself on their wedding night. His worried family sought to settle him by marrying him off – to Sarada Devi, then five years old – but he ensured that she grew up to emulate his celibacy.

Whatever the psychological wellsprings of this behaviour, its effect was to rehabilitate bhakti, an avid and essentially feminine devotion to the gods, which rather embarrassed the bourgeois Brahmos. It fascinated Datta, who prided himself on being a jnani, a reasoner. He recognised that Ramakrishna’s apparent childishness concealed an intellectual justification for his experiential surrender to the gods, perceived as tangible presences who were also manifestations of a single reality. In his prolonged trances, Ramakrishna sought advaita, a merger of selfhood with the world. Datta learned from him that the Upanishads – which, as the chronologically latest part of the Sanskrit Vedas, were known as Vedanta – contained a powerful vision of the unity of reality. Advaita Vedanta pierced the veil of illusion that separated the human and the divine, the individual and the whole, making differences of caste or creed fall away. Ramakrishna imagined Vedantists in their meditations as dolls made of salt who dissolved as they waded into the ocean of being.

These spiritual gymnastics led Datta to a discovery of India. He shaved his head and forswore the life of an Anglicised Bengali, embracing a sannyasin’s life of celibacy and mendicancy. The fireside mantras and stirring addresses he wrote to initiate his growing numbers of guru brothers severed them from the world and from their homes – Ramakrishna said these places were ‘infested with tigers’. But – like the late antique holy men studied by the historian Peter Brown – these gurus remained involved with the societies they had fled. In the years before his trip to Chicago, Datta went far beyond Bengal, visiting Hinduism’s holiest places. Like the Buddhist lama in Kipling’s Kim, whose ‘search’ for a holy river begins when he gets on a train in Lahore, Datta’s was a steam-powered pilgrimage. He viewed the British Empire and its railways as the ‘greatest machine that ever existed for the dissemination of ideas’. Having learned from Ramakrishna to prioritise the emotional aspect of popular devotions, he was able to dwell in sacred spaces, and to admire the extreme austerity endured by some holy men, without becoming captive to them. Though he moved among the poor, he lodged with the rulers of India’s princely states. They funded his Chicago journey, kitting him out with a watch and the orange jacket and turban that Americans took to be quintessentially eastern. He also received a final gift from the princes: the name Vivekananda (viveka is Sanskrit for ‘discernment’).

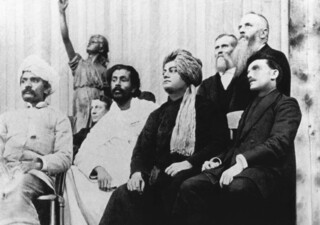

The World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago was not truly comprehensive. The only Anglican present had been forced out of King’s College London for heresy; Muslims were not welcome. The list of attendees was nonetheless extensive, including Jews, Japanese Buddhists and the Roman Catholic archbishop of Chicago. But what were their speeches meant to achieve? The parliament dovetailed with the Columbian Exposition, a celebration of Europe’s discovery of America and therefore of the supremacy of Western civilisation. For liberal Protestants, the point of dialogue with Jews or Hindus was to understand how Christianity could supersede their efforts at monotheism. But the Swedenborgians and Theosophists were keen for the parliament to formulate a new and truly universal faith. Theosophists were particularly sympathetic to the religion of modern Asia, where many of them had spent time: their attacks on missionaries won them many Asian recruits. But although Vivekananda benefited from the open mood they helped establish in Chicago, he disliked their magpie efforts to pick out what was valuable in other people’s faiths.

Vivekananda’s speeches in and around the parliament were much celebrated. He seized the contested heights of universalism for Hinduism, positioning it as superior to Christianity but also as a scientific alternative to Theosophy and the healing pretensions of Christian Science. He skilfully, even disingenuously, drew out from the Vedas a faith unblemished by the moral and intellectual shortcomings of Christianity. It didn’t burden individuals with guilt or scare them with the anger of a distant god. It released them from their ‘prison-individuality’ by locating the divine in all humanity. The Vedas didn’t teach an unscientific doctrine of creation, but had anticipated the idea of biological evolution by centuries: karma, which envisaged life’s continuous return in higher forms, was a version of the scientific plotting of organisms on a rising curve.

Karma, however, is supposed to be a circle, not a curve. Vivekananda made Hinduism sound more socially and intellectually progressive than the religion he knew at home. He didn’t mention the magical powers sannyasins like himself enjoyed; he celebrated the holiness of Hindu women, while glossing over the plight of child brides. For Harris, these things matter mainly because they suggest that Vivekananda didn’t aim at the systematic consistency that intellectual historians approve of. His teaching flourished in intimate settings far from the grandstanding of Chicago. The most important of them was Green Acre, a residential retreat in Maine set up by Sarah Farmer and Sara Bull to advance the parliament’s spiritual agenda; Vivekananda also joined homely ashrams in New York State and California. The book’s best sections are an emotional history of his work in these places. They evoke Vivekananda’s protean personality by mapping its impact on the people he attracted, showing how friendship and even love became vectors for ideas.

Who loved Vivekananda? Women, mostly. Historians often associate the 19th-century feminisation of religion with the defensive consolidation of Christianity and its missions abroad. But Harris shows that women like Bull and Farmer were vital to the search for a universal faith. Vivekananda’s hold over them was close to erotic, connected to his bulging eyes, exotic garb and outsized aura, which encouraged his admirers to think he was six foot two (not, as he really was, five foot eight). The turn-of-the-century cult of the guru was only possible because it had become so much easier to meet them in the flesh. The many Americans – including Farmer – who steamed to Haifa to stay with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá similarly concentrated less on his Baha’i creed than on the touch of his hand, the flash of his eye, the joy of being under his roof. Men fell for Vivekananda too, but his playful claim to be an ‘honorary woman’ who saw ‘no distinction of sex in the soul’ strengthened his magnetism for women. Though he treated them as spiritual sisters, he also aroused maternal instincts. Vivekananda admired the holy Indian women who imagined themselves mothers to the baby Krishna. He encouraged his followers to think of themselves as babies and to baby him too. The childless women who were among his keenest Anglo-American supporters readily spoiled this gifted child, whose health was brittle and moods were skittish.

This childishness was an attempt to crack Western complacency. Emerson and Thoreau had encouraged Americans to seek Indian wisdom on how to live, but their Transcendentalist Orientalism too often generated a pale, Protestant simulacrum of the original. Vivekananda emphasised the racial gap that separated him from his devotees. He blew cigarette smoke in women’s faces and demanded chocolate ice cream because he ‘too was chocolate’. These were daring provocations in a country whose hotels routinely turned him away as a Black man (they would also have been unthinkable in British India). But they titillated staunchly anti-colonialist women, some of whom were recent immigrants themselves, unsure of their position in America. Vivekananda also resisted the assimilation of Vedantism to Yankee Protestantism by refusing to tell his devotees exactly how to be good. Though he coached them in meditation, put them through initiation rituals and promised them work in India, the instruction stopped there. American women were already tightly corseted by notions of duty and self-denial – the last thing they needed was a monkish map to salvation. Vivekananda deliberately upset Bay Area vegetarians by complaining that he needed meat to work, not endless asparagus. When staying in their ashrams, he did not share the genteel angst about the division of household labour that had dogged American experiments in collective living since the days of Brook Farm. He preferred hanging out in the kitchen to teaching, spending his time grinding spices for curries or cooking up batches of rock candy.

Leon Landsberg, an intense Russian Jew who roomed with him in Manhattan while they gave classes there, wanted them to live off lentils. He was baffled by a guru who lived to cook and enraged by Vivekananda’s refusal to do the washing up. Too poor and foreign to succeed as a mendicant sannyasin, Landsberg had to moonlight as a bartender and was cold-shouldered by the other (teetotal) disciples. Vivekananda’s charm didn’t work so well in Britain, whose old colonial hands were more sceptical of his exotic mannerisms. His patron Edward Toronto Sturdy, a rich but ascetic Anglo-Canadian who had lived in India with a Brahmin cook, concluded that the eminent scholar Friedrich Max Müller was a sounder Vedantist than this corpulent, tobacco-stained guru who whinged about being forced to live off boiled cabbage. Vivekananda laughed off Sturdy’s charges as bad karma. In fact, he helped Müller, a German idealist who was no less of an oddity in Victorian England, to write a book on Ramakrishna. The two men hoped that a refined statement of Vedanta’s monism might insulate religion from scientific challenge, overcoming the divides – between the self and God, the natural and the supernatural – that bedevilled Christian theology.

Vivekananda did not build intellectual bridges between fixed systems so much as help to make new spiritual worlds with elements from the old. Although he became a famous yoga teacher in America, he did so by altering what yoga meant. At Green Acre, he mixed with seekers who were game for every ‘ism’ going, from New Thought to barefoot walks in dewy meadows. While mocking these enthusiasms, Vivekananda pillaged their vocabulary. Rāja Yoga (1896) was based on texts by the ancient yogi Patanjali, but without their crabbed soteriology. Vivekananda popularised yoga by simplifying it into the skill of breath control, which once mastered could measurably increase a practitioner’s energy levels. The rationale was pragmatic: it was true because it worked for people who tried it. Sara Bull suggested to William James that he write a preface to Rāja Yoga. James, the son of a Swedenborgian, yearned for a more open-ended model of selfhood, which could account for religious experience without resorting to an outmoded supernaturalism. An amateur Sanskritist and habitué of Green Acre, James had been struck by Vivekananda’s lectures there and by Müller’s presentation of Ramakrishna’s teaching. He adopted, or echoed, Vivekananda’s watery metaphors for the fluid mingling of mind and world. But he still refused to write the preface, finding the ‘monist absolutism’ of Advaita Vedanta too glib a solution to the riddles of consciousness. Müller too learned from Vivekananda without agreeing with him. His Ramakrishna book was intended to advance India’s conversion to a version of Christianity, teaching missionaries that its sophisticated inhabitants would not be swayed by crude methods ‘applicable to the races of Central Africa’.

Vivekananda was dogged by ill-health after his return to India in 1897, but the last five years of his life were still ones of intense activity. He needed to ensure that his Western friends didn’t end up inadvertently secularising Vedantism as they applied it to India’s social and political problems. Their cash financed the building of the Ramakrishna Math in Bengal, which remains the monastic headquarters for his mission. From this base, he set out to prove that Hinduism could develop a social service ethic, a ‘practical Vedanta’ or ‘karma yoga’, which strengthened the bodies and minds of Indian men, equipping them to tackle the famines that were devastating the country. Vivekananda was conscious of Ramakrishna’s warnings against entrapment by the world’s concerns and his view that ‘charity’ greased the wheels of imperialism by trying to alleviate the social harms it inflicted. He wanted his monks to do good without becoming Western do-gooders. Activism without renunciation was hollow. In his search for ‘eternal calmness’ in the midst of activism, Vivekananda often withdrew into a dreamy devotionalism that puzzled his Western allies. He also gravitated to the Bhagavad Gita. When the Krishna of the poem exhorted Arjuna to war against his own family, he urged action without care for the consequences. Dharma was central to Vivekananda’s activism; but although the word could be roughly translated as ‘duty’, it did not entail the pettifogging social conscience of Western Protestants, which reduced piety to measurable results. Although Vivekananda bullishly envisaged a new caste of warriors, his relationship with Indian nationalism remained oblique. He couched his anti-colonialism in a religious register and accepted social hierarchies, refusing to challenge caste and complacently idealising the ‘poor, the ignorant, the downtrodden’.

Harris ends and possibly over-extends her book by discussing the career of Margaret Noble, Vivekananda’s most prominent Western disciple in India. Noble’s feelings of ‘inner homelessness’ were typical of the women drawn to him. She inherited the anti-imperialism of her Irish father, a Wesleyan Home Ruler, but rejected his Christianity, before half-heartedly sampling spiritualism and Christian Science. At 24, scratching a living as a progressive schoolteacher in London, she encountered Vivekananda as a speaker in discussion clubs, the kind of intimate setting in which he shone. His elevation of renunciation over activism puzzled but finally attracted her; he claimed to see in her a future ‘world-mover’. After joining him in India and being initiated as a celibate disciple, Noble took the name Sister Nivedita and underwent Indianisation. She lived with Ramakrishna’s widow, Sarada Devi, and studied her winsome passivity. When plague broke out in Calcutta and there was widespread resistance against compulsory vaccination by the British, she joined Vivekananda’s sannyasins in organising clean-ups of the slums. She adopted a peculiar, not very Indian veil, which captured her idiosyncratic, eclectic anti-colonialism. She lectured and published books on ‘Kali the mother’, which vindicated the life-giving primitivism of her cult. During the agitation against Lord Curzon’s partition of Bengal in 1905, she cheered on the revolutionary young men who saw themselves as fighting for Kali.

Harris admires Nivedita’s gumption, but concedes that her determination to defend ‘the web of Indian life’ often involved the inversion of essentialising clichés; what British officialdom thought of as superstitious backwardness became organic holiness. Nivedita’s idealisation of Hindu womanhood ignored the vigorous efforts of Indian feminists to improve their condition. The defensiveness had a darker side, too. Nivedita explained Curzon’s tyranny as viceroy by observing that his wife, Mary Leiter, must be Jewish (she wasn’t). She was far from being the only anti-imperialist who believed that Jewish moneymen lurked behind British rule. Although she followed Vivekananda in calling for a non-sectarian nationalism that acknowledged Islam’s contributions to India’s history, her writings invoked a primordially Hindu nation. Her advocacy of what she called ‘aggressive Hinduism’ helped shape a religious rationale for political violence whose deep impact on modern India the historian Shruti Kapila has described. By the time Nivedita died in 1911, engaged in an ugly battle over money with Vivekananda’s patron Sara Bull, she had lost her grip on Indian politics. She would soon be forgotten in the West.

The internationalisation of Vedantist organisations which began in the last years of Vivekananda’s life secured the global currency of his name. In Vancouver, where he had landed in North America, a nondescript townhouse is the base for the Vivekananda Vedantist Society of British Columbia. It is affiliated to the Ramakrishna Math in Bengal, where the Vivekananda temple stands on the site where he was cremated. Yet a worldwide presence is not the same as being a guru to the world. Vedantism did not become the faith of the globe, nor did it catalyse the creation of such a faith. Despite – or perhaps because of – his eloquent vision of Hinduism’s potential universality, Vivekananda’s memory has fallen captive to Hindutva chauvinism in the land of his birth. Narendra Modi garlands his statues with flowers, a tribute from one world teacher to another. In recovering the dynamism of one historical manifestation of religious globalism, Harris has also explained why it collapsed in on itself.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.