Ahouse on the river bank is a bold choice for a hydrophobe, but Pam Waters lived for years next to the tidal River Witham in Boston, Lincolnshire, without it intruding on her life. She wasn’t tall enough to see over the grassy dyke at the bottom of her garden to the river on the other side, but since she hated water that was fine. Sometimes a fishing boat chugged by at high tide and looked down on her red brick terrace.

One evening in early December 2013 Waters was at home, feeling she’d bested the Christmas run-in. The holiday food was bought and she’d steam-cleaned the carpets. There’d been a story about east coast tidal storms on the TV that morning, but she didn’t follow the forecast closely and didn’t think of herself as living on the coast. She was on the phone to her stepdaughter when she heard a ferocious roar coming from the river side of the house. She went through into the tiny hallway that led to the garden door. Several tonnes of cold salt water was entering the house through whatever gap it could find. It was coming up through the floor and lifting the carpet. The door has an oval glass panel in the centre that comes up to Waters’s breastbone. In the glass she could see a line of brown sea, dancing, like water in the window of a half-full kettle at boiling point.

The great North Sea storm of 2013 came sixty years after the great North Sea storm of 1953. In Lincolnshire, nobody was killed, against 41 in 1953. Then, the storm was seen as one of those natural disasters that comes along every century or so, but the 2013 calamity – part of a series of floods that wracked Britain that winter – was portrayed by the government and media as an outrider of man-made climate change. And yet the government response was broadly the same as in 1953: money was rushed into building new flood defences. The best – a cynic would say the only – way for a community to get effective flood defences in Britain is to be badly flooded, to experience a devastating inundation of the sort that fills the news with shaming images of octogenarians in rescue boats and families astride their roofs, waving for help. The sea walls that proved too low to protect Boston in 2013, including the grassy dyke at the bottom of Pam Waters’s garden, had been put up after the floods of 1953. Higher walls and a barrier across the river were also mooted, but funding for flood defences nationwide was cut in the early 2010s as part of the Conservatives’ austerity programme. Only when Boston was actually flooded did the government come up with the money to get them built.

The first time I visited Boston, in late 2021, the finished barrier was less than a year old. A semi-cylindrical steel gate weighing several hundred tonnes now lies on its side on the riverbed, ready to be rotated by hydraulic rams to block the flow of water and seal off the gap in the town’s defences. Adam Robinson, the Environment Agency engineer responsible for building it, told me it would last for a century, and, even allowing for climate change, cut the chance of sea flooding for the 14,000 homes it protected to 0.33 per cent in any given year. Since 95 per cent of the population of Boston, 71,000 people, are at risk of flooding – more than anywhere else in England – this is a good thing. But Robinson said something that intrigued me: the barrier was also supposed to protect 6000 houses that hadn’t yet been built, designed or received planning permission. He’d got straight to the reason I was there, which was to find out why, in an era of melting ice, rising seas and swollen rivers, this low-lying English district, a reclaimed wetland with barely a free plot above the high-water mark on a spring tide, was still building out. Surely the barrier had been built to protect lives and existing property unluckily stranded in a climate change danger zone, not to enable new houses to be built into peril? Robinson laughed. ‘In a very simplistic way, yes, I can see that argument … If you took your scenario to the nth degree, shall we say, and looked at the tidal flood risk for the whole of East Anglia, right? Effectively you wouldn’t have anything on it.’

Mike Gildersleeves, a senior council planner working across south-east Lincolnshire (aka the silty part of the Fens, and, since drained, some of the richest farmland in England), said the powers above him were unable to reconcile their desires for economic growth, on the one hand, and safety from water levels on the other. ‘You’ve got two diametrically opposed planning objectives,’ he told me. ‘You’ve got an objective around growth, housing delivery, employment delivery, those sorts of things, and retention and rejuvenation of places. On the counter to that, you’ve got the approach to flood risk, which should be: “Don’t build there,” bluntly. “Build it somewhere else.” But … I’ve been involved in planning since 2005. I don’t think any government in that period and certainly not before has grappled with the challenge with two hands to actually say: “What do we do about those places that are in those areas that we believe are going to flood?” You could say: “Well, actually, we’re not going to invest in Boston any more. What we need to do is pick it up and move it somewhere else.” But we haven’t got the policy framework or the funding framework or the government drive to do that.’

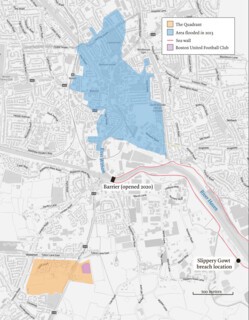

The government compels and incentivises each of England’s more than four hundred planning districts to hit a housebuilding target each year, and there’s no exemption for Boston just because it lies almost wholly on a high flood risk area. ‘It’s this awful thing,’ Hugh Ellis of the Town and Country Planning Association told me. ‘They’ve been completely forced into a corner: you either hit the housing target or you don’t. If the government doesn’t offer any other way of meeting that challenge, what the hell do you do?’ Not that Boston’s local politicians feel trapped. They’re up for growth. Between 2018 and 2021, the government demanded that Boston build – or, to be precise, demanded that Boston allow commercial housebuilders to build – 657 new homes. Boston hugely outperformed, building 1047 houses. The lion’s share was in a single development known as the Quadrant, in a suburb south of town called Wyberton, about three-quarters of a mile from the River Haven, which connects the Witham to the sea. It’s in what the Environment Agency defines as Flood Zone 3a, land with a high probability of flooding, though this doesn’t take sea defences into account. When construction began, the site was, on average, barely two metres above sea level, and four metres below the level the Haven rose to during the 2013 storm.

I have to dwell for a bit on the weirdness of that last sentence. It has ‘sea level’ both as a constant and as a value that goes up and down all the time. Human life and property by the trillion dollarload hang on the millimetre margins of the concept of ‘sea level’, but a closer look makes a seemingly hard-edged measure complex and uncertain. It turns out we’re all flat earthers by instinct. If I think about the concept of sea level hard enough, I experience disorientation, almost motion sickness, as awareness grows that I’m not living on solid ground but on a sinking chunk of planetary crust, on the surface of a not-really-spherical spinning globe, at the mercy of the nearest star, two icecaps and a capricious moon that sloshes the oceans to and fro like a child rocking in an over-filled bath.

Around the island of Great Britain, sea level – the reference point for the height of everything on land, from Pam Waters’s garden to Ben Nevis – is measured relative to the head of a brass bolt screwed to the floor inside a shabby red and white hut on the end of a pier in Newlyn, Cornwall. The bolt head is 4.75 metres above the average level of the sea, as measured every hour over the six-year period between 1915 and 1921. Oceanographers refer to this definition of sea level as ODN, which stands for Ordnance Datum Newlyn; when planners and housebuilders in places like Lincolnshire talk about land height they use the acronym AOD, or Above Ordnance Datum. The century-old bolt is still the reference for sea level, literally ground zero, as far as the UK is concerned, even though heights are measured these days with satellites and lasers (in 2016, they found they’d measured Ben Nevis wrong, and boosted it by a metre).

The bolt sits on a bed of granite, but mean sea level has risen since 1921. One of the reasons, for the southern English landmass – including Lincolnshire – is that we’re still recovering from the last ice age. The pop fact that southern England is sinking, and northern England and Scotland rising, makes it sound like a seesaw, but it’s more like what happens when you get up from a mattress. When the ice sheet and glaciers settled on top of northern Britain tens of thousands of years ago, they weighed on the crust and the viscous mantle below like a body on a yielding, elastic surface, but that weight also made the land around the ice sheet bulge up. When the climate changed and the ice left its bed, the weighed-down land began to spring back, and the bulging land, including what is now Lincolnshire and London, started to relax. This alone is making Boston sink by about the thickness of a pencil every decade.

The main cause of the rising sea level is, of course, higher temperatures caused by human-induced emission of greenhouse gases. Higher temperatures warm the sea, making it expand. They also cause the polar icecaps to melt, increasing the sea’s volume, and thus its height. Between them, the Arctic and Antarctic are discharging 424 billion tonnes of fresh water into the sea each year, as much as flows into the Amazon from one of its big Andean tributaries. But the icecap melt is outside the cycle of evaporation and rainfall; it’s a one-way pour, and the melt rate is accelerating. Since 1921, the sea level around Britain has gone up by about twenty centimetres AOD. For most of the 20th century, it was increasing by 1.3 mm a year. By the early 1970s, that had gone up to 1.9 mm a year. Since 2006, the increase has nearly doubled, to 3.7 mm a year. Everything that gets built now in Lincolnshire, and anywhere in coastal Britain, is supposed to be built with an eye on the climate scientists’ best guess for the next hundred years.

There’s a popular map on the internet showing what the British Isles will look like in 2100, with low-lying land erased by rising sea levels as the Earth heats up. Ireland is a handful of tattered scraps melting into the waves, Dublin and Galway drowned. The Central Belt of Scotland is an open strait. Liverpool and Bristol are deep in Davy Jones’s locker. The remnants of Devon and Cornwall are an island. Leicester is at the mouth of a vast inlet stretching west all the way to the Malvern Hills. Oxford is fathoms down. The west and north of Britain are recognisable, but eastern England has vanished. Watford and Kingston-upon-Thames are coastal towns, straining to see each other across the broad, deep channel covering London. Sussex, Kent and Essex are mostly seabed. Suffolk, Norfolk, Cambridgeshire, Lincolnshire and much of Yorkshire have disappeared. Here and there, we imagine a church spire or the top floors of City skyscrapers breaking the surface. Kelp forests choke the ring roads, barnacles crust the Wembley arch, mutant eels writhe in the turbine halls of abandoned power stations.

The map is terrifying, extraordinary and untrue. It shows the result of the complete melt of all the world’s ice – both polar icecaps, along with all the glaciers – in less than eighty years. Even the most severe scenarios of global warming suggest this apocalyptic disaster would take centuries or millennia, if it ever happens. Maps like this are a thrill for catastrophists, and those high on end-time ambience, but don’t help if we actually want to defend ourselves against the consequences of our long fossil burn. They’re reassurance for do-nothing shoulder-shruggers that there’s no point in acting against man-made climate change, because we’re doomed. And when the Britain-drowned-in-one-lifetime maps are set against the predicted reality, it makes that reality seem deceptively mild. The latest worst case version of a worst case emissions scenario – a scenario many scientists consider too pessimistic – would see an increase of 1.13 metres in the sea level at Boston by 2100; a more likely scenario predicts a rise of 54 centimetres.

‘When we’re talking in terms of millimetres per year there’s a level of complacency among the public and I think government as well, because it just seems negligible,’ the chief scientist at the National Oceanography Centre, Angela Hatton, told me. ‘The 1953 storm was a 1-in-400-year event when it occurred. But we had another event in 2013 that was a similar scale … that was a 1-in-400-year event, and now we’ve had two of them in the space of seventy years.’ Uncertainty over the scale of sea-level rise shouldn’t be mistaken for doubt that the process underlying that rise is real, and speeding up. There is plenty of scope for shocks. ‘There are certain aspects of ice-sheet dynamics that are still very uncertain,’ she said. ‘If you look at the latest IPCC report, they’ve said that if a certain ice melt scenario occurs, it could just blow all the predictions out of the water and we could see a catastrophic sea level rise.’

One of the drawbacks of the fantasy maps of drowned Britain, a drawback shared by many much better and more useful graphics, is that they portray the meeting of sea and land as a fixed line, an absolute boundary, as if there were two sovereign realms, the land and the sea, with a precisely demarcated border. The sea invades, the land is conquered, the land retreats, the sea has won for ever. The land must be defended, the land must be fortified, the line must be held. Or you give in and surrender permanently to the sea. But in nature, there’s no such border. Climate change apart, the line between land and sea moves minute by minute with the tides, the waves, the wind and the multi-year cycles of the moon’s orbit. Invasion and retreat happen twice a day, and the difference between high and low tides on the British coast – 6.38 metres in Boston in 2022 – is many times larger than the anticipated sea-level increase from global warming. The south-east Lincolnshire fenland has seen radical natural changes in its coastline and the course of its rivers over the past thousand years of recorded history, and until relatively recently the people who lived there worked with the tides. They fished and caught eels, hunted wildfowl and grazed cattle and sheep on lush salt marshes that were regularly inundated by the Wash, the estuary between Norfolk and Lincolnshire. Efforts to protect people’s houses and smallholdings from flooding go back to before the Romans, but it was only when large-scale drainage transformed the landscape that the area began to move towards the point it has reached today, a less well-funded and less systematic version of the old Dutch way of defence, where the water is walled away from the land by a line of earth, steel and concrete, a barrier that not only protects lives and property but blocks the sight of the sea. Behind the wall, the sea might be higher than the ground you stand on, but you can still forget it’s there.

Chestnut Homes, the company building the Quadrant, and Boston Borough Council, which provided the planning permission, claim they’re safe behind the new barrier and the sea wall that runs along the banks of the Haven and the edge of the Wash. The barrier was built to defend against sea heights of 7.55 metres AOD, and after the 2013 floods the sea wall was strengthened and raised to 6.5 metres (it will probably be built up further later this century). On the face of it, that’s a big safety margin. In 2022, the highest spring tide at Boston was 3.55 metres AOD. Without the wall, that would be enough to flood most of Boston, including the original Quadrant site; with the wall, that high tide is 2.95 metres from the top. But there are other factors. We’re approaching a low point in an eighteen-year lunar cycle. Its next peaks, in 2034 and 2053, could add thirty centimetres to a high tide. There’s the highly uncertain but accelerating increase in sea level due to global warming and land sink, which could easily mean another thirty centimetres by mid-century. Most perilous of all are storm surges, as happened in 1953 and 2013, where a combination of low atmospheric pressure and strong winds can add as much as two metres of sea height to the existing tides. Put these guesstimates together, and Boston’s margin of safety shrinks to the length of a toddler’s arm.

Chestnut Homes, a private firm based in northern Lincolnshire, formally asked Boston Borough Council for permission to build the Quadrant in 2014. Chestnut wanted to build up to five hundred houses, a supermarket, a petrol station, a restaurant, a pub, a ‘hot food takeaway outlet’ and a sixty-bed hotel on the main road south out of town, the A16. It was a big project for a middling town, with a lot of money riding on it. If the average price of the houses reached £200,000, they alone would be worth £100 million. But consent wasn’t a given. The Environment Agency was bound to be uneasy about the below-high-tide location, regardless of the sea wall. Even though the council was only able to countenance building in Flood Zone 3 because the government insisted it permit the building of hundreds of new houses somewhere, there was still the risk the government might object if the council said yes.

As a package, however, the Quadrant came with extra incentives for Boston. As well as a proportion of affordable housing, Chestnut’s application was bundled with two other elements the council would be hard put to refuse. Both had their origins in what were, for Lincolnshire, a strange few weeks in 2007. In a bloodless localist uprising in May, Boston’s mainstream parties were voted out of office by a single-issue movement demanding a new bypass. The Boston Bypass Independents won 25 out of 32 seats at the local elections, wiping out Labour, which lost 11 seats, and leaving the Conservatives with only five councillors. At the next election, the Bypassers lost most of their seats, without having got their road. But local Conservatives haven’t forgotten the shock of their drubbing, or the notion that a bypass could be a vote magnet. Just as the national party absorbed Ukip’s Brexit project in order to neutralise a threat to its own power, so Boston’s Tories – it has been a Conservative town for the last century – cultivated an obsession with the new road.

Even as the Bypassers were consolidating their hold on power, equally disconcertingly to Bostonians, the town’s football club, Boston United, faced ruin. In 2006, after years of investigations and appeals around claims of secret and illegal payments to players, the team’s former chairman, Pat Malkinson, and its manager, Steve Evans, were given suspended jail sentences for £245,000 worth of tax fraud. Despite this, Evans kept his job. The club limped on through the 2006-7 season, bumping along the bottom of the fourth tier of the football league and bleeding cash. By season’s end, players weren’t being paid, had to travel to away matches by car and were locked out of their own training ground. Boston’s directors knew the club was about to go bust, but wanted to time the announcement so the consequent mandatory deduction of ten points wouldn’t either get them relegated, or doom them to start the new season with a handicap. Relegation wasn’t decided until the last game of the season, when Wrexham applied the 3-1 coup de grâce. A few minutes before the final whistle, the directors put the club into a form of administration. Their attempt to game the system was futile. The football authorities dropped Boston down two divisions, and with the club owing its creditors £3.5 million, fans had reason to think it was the end.

The club’s shirt sponsor that season was Chestnut Homes, and an executive from the firm, Neil Kempster, sat on the board. On 17 June, there was a crisis meeting of the board and supporters to brainstorm ideas to save the club. Kempster was on holiday, so the owner and boss of Chestnut, David Newton, sat in for him. Newton – who was not a Bostonian, or a Boston United supporter – said later that he experienced a sentimental epiphany. ‘I sat there with a lump in my throat,’ Newton told the Boston Standard. ‘I spent the rest of the day pondering what could be done to save the club and trying to get back to my head ruling my heart rather than the other way round.’ A few days later, he bought the club.

Newton saved Boston United, invested in it and ran it properly; Chestnut’s promo material speaks of wanting to ‘put something back into the community’ and ‘the significance of the game to the town’s wider civic aspirations’. At the same time, Newton seems to have been aware of the future Quadrant site when he bought the club. He had been building homes nearby since the early 2000s, and the same year he bought Boston United he commissioned a survey on the site to make sure it wasn’t hiding any archaeological treasures that might get in the way of development. Successful housebuilders think decades ahead. At some point in the next seven years, Chestnut began discreet conversations with the authorities, and when the council received the planning application in 2014, the project included a new 5000-seat stadium for the football club and a very short section of bypass. Without permission to build the houses, it was made clear, the town would get neither. The application, produced for Chestnut by a Harrogate outfit called Signet Planning, listed six other English towns where, in exchange for a big, jobsy boon like a stadium, councils let developers build on sites they’d normally be kept away from. Such sweeteners are commonplace, and legal, but it gives them edge when the sweetener is being offered in the context of flood risk.

It’s hard to be sure how much Chestnut paid for the 28-hectare site, or when; one Land Registry document referring just to the land where the first few streets of houses were built gives a price of £3 million. Land for the stadium was acquired on a long lease from the diocese of Lincoln. The scale of Newton’s endeavour showed in the enormous labour that went into the planning application itself, before a single shovel went into the ground. Eleven different consulting firms produced more than three thousand pages of documents between them.

Consultants from Signet Planning toured rural Lincolnshire to gather inspiration; they wrote of different shades of brick, of swales, of mud and stud, of giving the Quadrant houses a ‘village feel’, although it would be, they acknowledged, a village bordered by two massive roads, a football stadium and a 7000 m2 superstore. ‘At the heart of the site,’ Signet proclaimed, or confessed, ‘there is a roundabout.’ A firm from Doncaster produced a study on whether Quadrant residents would be deafened by traffic noise (they wouldn’t). A company from Sutton-in-Ashfield pored over the plans for the stadium lights and decided people living nearby would experience brightness ‘no more than moonlight’. They came from Louth to look into drains, from Wakefield to look at buses and from Leeds to investigate air pollution, and gave the thumbs up. The archaeologists found Roman remains, but not enough of them to warrant a build-blocking dig. Naturalists rummaged for protected animals. They found pheasants, wood pigeons, collared doves, wrens, blackbirds, blue tits, great tits, carrion crows, starlings and reed buntings; they found four badger setts, without badgers in residence, which they recommended sealing off. No evidence of bat activity, or of great crested newts. Water voles would be translocated. Chestnut said a public consultation it carried out in late 2013 showed that most people backed the project. The front-page splash in the Boston Standard when Newton announced his plan displayed a CGI mock-up of the stadium with the headline ‘Field of dreams for whole town’.

Newton declined to be interviewed in person or remotely for this article. Asked by email whether he already had the Quadrant plan in mind for that site when he bought the club, Newton replied:

The club had no assets; therefore, it was essential that enabling development also took place to help deliver the stadium. The ‘Quadrant’ land was identified, as was a suitable site for the new stadium … [it] was a logical development site, as acknowledged by Boston Borough Council. Although the stadium is not an ‘act of generosity’, we are delighted that it has added pride within the town and is being used extensively.

All the lights were green, except the one marked ‘flood risk’. The Environment Agency was sceptical. In a letter to the council in September 2013, before Newton went public with his plans, an EA official called Rob Millbank warned that no houses built on the site should have living space on the ground floor. He suggested the Quadrant could be ‘an exemplar in flood risk terms’, perhaps by offering ‘an area of community safe refuge’ during a flood. This notion was ingeniously taken up in the planning application. One consultant explained that its potential use as a flood refuge for evacuees from the Quadrant’s houses was an argument in favour of building the stadium.

In the Netherlands, the government is obliged by law to erect almost absurdly robust sea defences – strong enough to reduce the risk of any Dutch citizen dying in a sea flood to 0.001 per cent in any given year, a 1-in-100,000-year event. In Britain, the Environment Agency is under no legal obligation to protect anyone. Technically, it’s down to individual property-owners to protect themselves against drowning and flood damage. In practice, the EA tries to make the best use of a limited budget to protect the most vulnerable areas. The post-1953 sea wall in Boston was supposed to protect against a 1-in-200-year tide, i.e. one with a 0.5 per cent of happening in any given year; the barrier and other improvements since 2013 have increased that to 0.33 per cent, or 1 in 300 years. The current system was designed to hold good until 2115. But these calculations relate to a single question: is the wall high enough to keep the sea out? Will the water, in flood engineer parlance, overtop the defences?

The Environment Agency, however, expects housebuilders to carry out a flood risk assessment that explores a further and somewhat less likely danger than the already unlikely danger of the walls not being high enough. What if they fail? What if the sea breaches them? In either scenario, the EA demands a strategy for ‘mitigating’ the danger – making houses safe from floods – or ‘managing’ it, a lesser, and less expensive, degree of coping. This involves drawing up evacuation plans, or building houses that can be more easily repaired after a flood, so called ‘flood resilient construction’. Chestnut Homes knew they had to mitigate against overtopping, but were unhappy about having to mitigate for a breach. The disagreement resembles the 19th-century argument in Britain about railway brakes. The rail companies argued that their trains were safe because they were equipped with brakes; the government argued that they should be equipped with more expensive, failsafe brakes. The risk of things failing that are, in themselves, designed to cope with an emergency is known as ‘residual risk’, and the EA expects flood planners to prepare for it.

Accordingly, AECOM, the firm Chestnut hired to carry out the flood risk assessment for the Quadrant, modelled the effects of a breach in the wall on the edge of the RSPB wildlife reserve at Frampton Marsh, close to where the Haven and the River Welland discharge into the Wash. The hypothetical breach was more than three miles from the Quadrant site, but the effects were severe. Taking predicted higher sea levels into account, a bad storm surge combined with a breach at that point in 2115 would cover the entire Quadrant site in water to a depth of between one and two metres, putting everyone there in the government’s highest category of jeopardy – ‘Danger for All’.

AECOM reckoned the flood danger to people using the planned stadium, shops and restaurants could be dealt with relatively easily, but the homes would be vulnerable. The site was deemed by the EA to be in Flood Zone 3, the category of highest risk. According to government rules, the council shouldn’t let houses be built there at all unless there were no less risky alternative sites and the benefits to the community outweighed the danger. Even then, Chestnut would have to show that people living there would be safe for a hundred years. The company would also have to persuade the EA that the risk to the people living close to the new development wouldn’t be increased. To the north, south and west, the Quadrant’s houses would neighbour residential streets that had been there for decades. The EA has no power to stop councils giving permission for new buildings. But without its blessing, given the size of the project, the council and Chestnut would face the unpleasant prospect of the eye of government swivelling towards Wyberton to see what was going on.

The EA’s proposal for extra-height houses – three storeys instead of two, with the lowest floor being floodable garage space – was shot down early on. In minutes of a meeting in 2013 that I got hold of through a freedom of information request, Paul Edwards, the council’s point man on the project, described it as ‘a poor design solution’. It’s easy to see that it wouldn’t have pleased Newton either. The houses would have been more expensive, and their unusual appearance would have advertised to buyers the shortcomings of their location. Besides, Chestnut would have had to design them. Despite its embrace of the language of villagey distinctiveness, one of the ways the company keeps costs down is by using the same handful of house designs across its many Lincolnshire developments.

AECOM’s solution was brutally simple. If the land was too low, and raising houses was out of the question, the land itself would have to be raised. The consultancy suggested layering up huge quantities of earth to create a ‘development platform’ five metres above sea level, and building houses on that. On a grand scale, it was a version of the medieval terpen that can still be seen in the Netherlands, where houses and churches were raised on mounds to protect them from storm tides. Other housebuilders in English flood zones had used this idea to get round planning restrictions. The notion was enough to advance the project: the EA lifted its fundamental objection, and in August 2014, at a meeting where a pro-stadium petition from Boston United fans was handed in, the council gave the Quadrant the go-ahead, subject to Chestnut giving more detail about how its mound would work.

The trouble was, neither side really liked the idea. From the EA’s point of view, the mega-terp might protect the new development, but it would displace flood waters, increasing the danger to existing houses. AECOM’s own research suggested that while some of the houses around the Quadrant would be made safer by the creation of an enormous, flat-topped mound, others – up to 274 of them – would be more exposed to flood hazards, without compensation or redress; without even being told of the risk. For Chestnut, the mound was a nightmare. It would be horribly expensive to build up all that soil. It would look odd, since parts of the site would not be raised, and its appearance, he thought, would put buyers off. Roy Lobley, the flood consultant Chestnut hired to turn AECOM’s idea into a practical plan, told me that Newton and his team resented the notion underlying the EA’s approach to risk, that the sea defences might fail – what was the point of building them, then? At one point, Lobley said, Chestnut looked into getting a data consultant to quantify just how unlikely it was for there to be a 1-in-200-year storm the defences were designed to cope with and a breach in exactly the right place on the coast to threaten the Quadrant site. ‘Sometimes,’ Lobley said, ‘I think people in the Environment Agency forget that we’re talking about an extremely unique event here.’ Gildersleeves, for the council, made the same point. ‘They will say we shouldn’t assume that the defence is there because the defence could fail. And my argument on that is, well, you’ve just spent £120 million on a barrier and you’re saying to us we’ve got to assume it fails? That is illogical.’

So Chestnut dumped the mound. Lobley’s suggestion was that the ground be raised slightly, the exact height depending on the type of house. He also argued, on Chestnut’s behalf, that the company didn’t need to mitigate against the possibility of a breach, just come up with a way to manage it. The EA shot the proposal down briskly as Chestnut backing out of its earlier obligations, and as going against the advice they gave, consistently, across the country. ‘Chestnut seem to think they have ensured the development will be safe as there will be an “area of safe refuge” for everyone, a flood evacuation plan, and then finally something along the lines of “The Boston Barrier will soon be here to remove all risk,”’ Millbank wrote sarcastically in an email to colleagues in 2016. Lobley told me: ‘So Chestnut was arguing, well, why do we need to mitigate for a breach depth that may be quite significant on site but may never happen? “We can manage it maybe with flood evacuation.” But the Environment Agency won on that.’

Asked about Chestnut’s initial resistance to designing for a breach, Newton replied: ‘The modelling for the flood risk assessment was carried out on both breach and overtopping scenarios, and the flood mitigation measures were established on that information.’

In the end, the agency accepted a version of Lobley’s scheme. His plan didn’t bring everyone’s living space above the predicted breach flood level, so the houses of those still conceptually underwater would be fitted with flood-proof doors and have their electrics raised. Houses and flats with bedrooms on the ground floor would be raised by four metres, protecting them against a storm tide that would only happen once in a thousand years; others would be raised 3.91 metres, proofing them against a 1-in-200-year event. But some would just have to hope their waterproof doors held fast. As for the increased danger to the Quadrant’s neighbours, the agency no longer mentioned it. By this time Millbank’s name had disappeared from EA correspondence and another civil servant was handling it.

You might assume that in 2017, after the EA accepted the Quadrant plan, the council met to give Chestnut homes the final go-ahead, and work began. In fact, it was the other way round: Chestnut started work, then the council said they could and then the Environment Agency said it had no objection – a reflection, perhaps, of the weakness of the regulators, and of the keenness of councillors to see their town win a stadium, and a sliver (about a third of a mile) of bypass, and a hundred affordable houses, and to be able to feel that Boston was booming.

In retrospect , it seems odd that people ever thought there was a chance the Conservative government would nip the Quadrant in the bud. It would have been plausible a decade earlier, under Labour. In 2008, when Boston’s Tory MP managed to get Parliament to debate the bypass, a Labour minister, Jim Fitzpatrick, said that, ‘in considering the case for new development in or around Boston, one critical factor … is the risk of flooding, whether that be from rising sea levels or extreme weather resulting from global warming.’ Two years later, Boston council officials were briefing the media that the worst-case scenario the EA demanded Chestnut make provision for – a 1-in-200-year storm tide and a breach in flood defences – meant the town would be able to build a few score new houses a year at most. David Seymour, a Boston Standard reporter who was at the meeting, told me how surprised he’d been when officials drew journalists aside to tell them that Boston’s big housebuilding days were over, and the future of the town, commercially speaking, was packaging up its history for tourists.

A few weeks later, Gordon Brown’s Labour government was voted out. David Cameron’s Conservative-dominated coalition moved rapidly to dismantle Labour’s system of regional planning. In came district-scale housing targets and subsidies for first-time buyers; the idea of flood-related restrictions on Boston housebuilding – which the town’s mix of Conservative and independent councillors had never liked – was set aside. Far from being sceptical about the Quadrant, the government subsidised it massively. Newton presented himself as a businessman eating into his company’s profits to give Boston a stadium, a bit of bypass, a hundred affordable houses and some cash (£866,000) to help with the health, education and public transport needs of the residents. Maybe. But this supposedly commercial project was promised £4.75 million from the government’s Growth Deal before the EA had even signed off on it, and another £3.5 million from its Housing Infrastructure Fund. Later, when the Conservatives set up Town Deals to channel funds to poorer towns – 87 per cent of the towns chosen had Conservative MPs – they insisted the plan for spending the money be drawn up by an unelected board, which had to be headed by a businessperson. The man chosen to head the board in Boston was Neil Kempster, Newton’s right-hand man at Chestnut Homes.

‘The Quadrant is a commercial development,’ Newton wrote to me, ‘but due to high costs of delivering such large projects it is not unusual to receive some public funding.’ Kempster did not respond to my emails, but Newton pointed out to me that the Quadrant project preceded the setting up of the Town Deal. ‘To have Neil’s development expertise on that board must be helpful to the members. Chestnut Homes have no interest in any of the projects being championed under the Town Deal. We are proud that Neil is prepared to give a lot of his personal time to the board.’

I suggested to Paul Skinner, the Conservative leader of Boston council, that it had been quite cold-blooded for councillors to agree to building the Quadrant knowing that it increased the hazard for existing properties. ‘The number of properties that are flooded because of it – I can’t think of any, to be quite honest,’ he said, as if I was talking about the past, rather than the future. The road was what it was all about, he said. Chestnut is in talks with the council about Quadrant 2, which will involve more houses and another bit of road; where Quadrant 1 had a stadium, Quadrant 2 will have a marina. And so, according to Skinner, it will go on. ‘Quadrants 1, 2, 3, 4 as they go around the town will actually provide an envelope for development,’ he said. Skinner sits with Kempster on the Town Deal board.

Quadrant 1’s road and stadium have been built, and many of the houses are occupied. There’s no sign of the superstore, but the promised food outlets are open: Papa John’s Pizza, Burger King and Greggs. One evening I drove down a dark country lane on the edge of Wyberton to the home of Richard Austin, who led the Bypass Independents to victory in 2007. He’s in his eighties now. His wife, Alison, is also involved in local politics as an independent. She would have chaired the 2017 meeting that rubber-stamped the start of housebuilding on the Quadrant, but recused herself under pressure from other councillors who thought she lived too close to the site.

We drank tea in their large, plain kitchen. Both Austins were in favour of Newton’s project. When I talked about the site being prone to flooding, Alison Austin pursed her lips. ‘Prone to flooding,’ she said, ‘is not what I think would be the right word for it. That assumes every conceivable defence fails simultaneously.’ Richard Austin said Wyberton hadn’t flooded since 1810. I said this made me think of all the news footage I’d seen over the years of people in floods. They never say: ‘This happens all the time.’ They always say: ‘This has never happened before.’

‘The chance of being flooded is 0.05 per cent,’ Alison Austin said, accidentally diminishing the risk by a factor of ten. ‘That is a very small figure.’ Her husband said that when they had a breach in 2013, half a mile down the road, ‘it was pretty well contained by the medieval bank.’ He was referring to a low, derelict, overgrown sea wall from the Middle Ages, set back from the modern levee. ‘You can be sure that all those weak points have been dealt with,’ Alison Austin said. I asked the Austins the same question I’d asked Paul Skinner, about the increased flood hazard for the older houses around the Quadrant. If a breach occurred, ‘the whole of the centre of Boston has been obliterated,’ Alison Austin said. ‘So I think at that stage it is somewhat academic. Half of London will have gone. It really really will. And every place along the east coast, if it is like that.’

There seemed a cognitive dissonance between the insistence that there was virtually no chance of the defences being breached, and the acknowledgment that the defences had been breached as recently as 2013. Despite the construction of the barrier since then, and the concurrent toughening and raising of the sea walls, it isn’t a fantastical notion. It’s eerie, reading the minutes of a 2013 meeting in Lincoln of the developers, bureaucrats, politicians and regulators, when the Quadrant project was gathering momentum, to realise it was happening when the people of Boston were still clearing up after the worst storm and flooding for eighty years. Newton, sceptical of breaches, was telling the meeting that his new stadium would deliver the first part of the new road they wanted so much; the EA representatives were saying that a few days earlier an actual storm had actually breached the sea defences at Wyberton, although flooding didn’t get as far as the Quadrant site. Was it reassurance, or warning? Not long ago the EA tried to stop using expressions like ‘a 1-in-200-year storm’ in favour of the formula ‘a 0.5 per cent chance each year’, to make it clear that living through such a storm doesn’t mean you’re safe for the next two hundred years. Especially when our small planet is heating up.

On 4 December 2013 a low pressure system, a cyclone, formed between Greenland and Iceland, deepened as it merged with another system off Norway, and moved south, accompanied by furious winds. Next day, as it passed northern Scotland and entered the North Sea, pressure fell precipitously, the phenomenon known as a ‘weather bomb’. The North Sea is shallower than the Atlantic, and from north to south narrows like a funnel. The cyclone sucked at the water, the wind drove and squeezed it into a tighter and tighter space between the coasts and the seabed, and the moon dragged it up to tides that were set to be unusually high. It was an extremely powerful storm surge, and the land was in its way. Flooding struck the North Sea coast in step with the high tide, moving anti-clockwise, starting in Wick at lunchtime, hitting Lowestoft at 10.30 p.m., moving on to Kent, reaching Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark in the early hours of the morning.

There was flooding in Newcastle, Whitby, Scarborough and the villages of the Humber. The tide gauge at Lowestoft, which was partly flooded, recorded a surge of two metres above astronomical high tide, higher than in 1953. The railway in eastern Suffolk shut down. Sixty centimetres of water, the shallow end of a kids’ swimming pool, becomes an enormous force when it’s part of the living sea; ordinary brick walls won’t always hold it. In Walcott in Norfolk, ten houses were so badly damaged that they had to be demolished. Fifty more were temporarily uninhabitable. In Hemsby, villagers were at a fundraiser for new sea defences when the storm hit. Homes fell into the sea or were left hanging over the scarp of the backshore. ‘We stood by the patio doors and we could actually see the kitchen fold,’ said one man whose house largely disappeared. The lifeboat crew in Wells-next-the-Sea filmed themselves being driven back up the stairs of their boathouse by a rush of foaming water. In Burnham Overy Staithe, my partner’s father walked down the lane seaward from his house, usually separated from the sea by an expanse of marsh, until his torch beam met the black writhe of water. It sounded, he said later, like something boiling.

The land itself was reshaped. Hugh Drake, a farmer at Friskney on the coast north of Boston, lost 25 acres when the sea breached his private dyke. He had to build a new sea wall further back. The flooded land he managed to keep had such a strong dose of brine he couldn’t plant on it for two years.

It could have been worse. Nobody drowned. Forecasters had a much better idea of what to expect than in 1953, the authorities were much better at getting the message out, and an army of responders were ready. Thousands of people were evacuated. In some places, the sea rose higher than it had in 1953, but the wind was blowing down the coast, instead of against, and waves weren’t so high, putting less pressure on sea defences, which were anyway an order of magnitude superior. And yet the sea found ways through. The Thames Barrier closed in good time to protect London, the best defended of England’s vulnerable coastal habitations, but Boston didn’t yet have a barrier.

The Haven was straightened by navvies and horsepower in the 18th century. Removing its meanders had the side effect of making it easier for storm surges to rise straight into town. On the early evening of 5 December 2013 the storm propelled the high tide down the Haven and into the centre of Boston. The water rose steadily until, in an orderly, roaring curtain, like a great weir, it began to stream over the top of the defensive walls and into the streets. The Bizzarro restaurant on Wormgate was hosting a Taste of Venice night. Soon the street was filled with water deep enough for gondolas. The offices of the Boston Standard were flooded. A pumping station meant to prevent flooding was itself flooded and three pumps ruined. The floodlights illuminating the great medieval tower of St Botolph’s Church, known as the Stump, shone through a salt waterfall. Some sixty centimetres of water rushed into the church, where John Cotton, patriarch of New England, had made his reputation; it caused a million pounds’ worth of damage. A stone outside showing two and a half centuries of high-water marks has now been engraved with 2013’s level: the highest yet, by a good third of a metre. Fifty streets had some standing flood water. Of the 2800 properties flooded in the 2013 storm, 800 were in Boston. Half of the flooded households didn’t have contents insurance; some people were still living in temporary accommodation a year later. Mounds of ruined furniture, sodden carpets and trashed white goods piled up outside the flooded houses. Tonnes of damaged plaster had to be stripped from walls so the brick could dry.

I went to some of the areas that had flooded. Two streets of Victorian houses stand at right angles opposite a park not far from the Witham. They looked similar, and on the same level, but flooding reveals small margins. One street, where the houses were larger, was slightly higher, and hadn’t flooded. The other, a terrace of smaller properties, had been inundated to above ankle level. Most of the residents seemed to have come originally from one of the ten Eastern and Central European countries that joined the EU between 2004 and 2007. It was the second time I’d noticed that a high proportion of people from the so-called ‘accession’ countries were renting living space in Victorian artisanal housing in flood-vulnerable streets. At the time of the 2011 census, they made up 10 per cent of Boston’s population. The most recent census results show this has risen to 18 per cent. The arrival of so many Lithuanians, Poles and Romanians in a short time was seen by many observers as a reason why Boston became, in 2016, the most pro-Brexit town in Britain: 75.6 per cent of voters opted to leave the EU. Supporters of the Quadrant say foreign-born workers are essential to the area’s vegetable farms and food processing businesses, and new houses are needed to reduce overcrowding in old properties in town. I was sceptical that anyone doing field work would be able to afford a mortgage, but in Tawney Street I met a Lithuanian-born woman called Asta, who works harvesting vegetables and owns one of the terraced houses that flooded. She bought it with her former husband when houses were cheaper. She’s been in Boston for eleven years, but still struggles with the language, so we conversed in Russian, which she learned in her Soviet schooldays. She said the flood had been frightening and had done a lot of damage; when the water receded, their wooden floors had seemed fine at first, then began to warp and rise. I asked if she’d fled the house. ‘Where could you run to when the water was everywhere?’ she said.

Asta told me her cousin in the London Road area had had it worse. Fridges had been afloat. That’s the area where I met Pam Waters, watching a Gordon Ramsay show in her dressing gown before she headed out for her evening shift in the kitchen of a nearby bar. She made me a cup of tea and we sat in her little backyard, on the side of the house away from the river. The 2013 storm was a diffuse event, without even a name in Britain (different European weather services called it Xaver, Bodil, Sven, Cameron and the Santa Claus Storm), and there were many different flood and wind disasters that winter. Waters had never talked about it to a journalist before. She’d switched off the electricity, put the cat in a travelling cage, borrowed some candles from her neighbour – who later jumped off her stairs into the metre-high flood water on her ground floor and swam to a rescue boat – and took refuge with her husband in the upstairs bathroom. From the window they could see the dark water reflect the flicker of shorting lights. They heard the noise of bins bumping against one another and eventually the water pouring out with the ebbing tide, making the same roar as when it came in. Then the stink began. Even with the doors shut, seaweed somehow got into the house. Everything on the ground floor was ruined, except the microwave the family used to cook their Christmas dinner. The insurance company offered to pay their claim in Argos vouchers. ‘For a few years after that, I never settled,’ Waters said. ‘I just couldn’t. It scared me so much. I didn’t like looking out the windows at the back. I don’t think about it now. The barrier’s made me feel safer. Plus the fact that the wall’s been made higher.’

Waters experienced the effects of a storm tide overtopping defences. Down the Haven, closer to the sea, something more ominous happened. Inland from the sea defences of the Lincolnshire Fens is a whole other aqueous circulatory system, old, fragile and complex, that keeps farmland from reverting to its marshy state. Rivers are banked in, as are river-sized drainage channels, and pumps placed strategically in a precise filigree of farmers’ ditches. One of the arcane public bodies that runs these systems, the Black Sluice Internal Drainage Board, manages the fresh water levels inland of the west side of the Haven. On the night of the storm, all was quiet as far as the Black Sluice control room was concerned: the problems its pumps are set up to deal with, bloated rivers and land drenched with rain, were absent. Unexpectedly, one of three pumps in Wyberton Marsh, near the sea wall, started pumping water, then the second, then the third. Calls came in from people telling them that water in small brooks was flowing the wrong way. ‘We’re scratching our heads because we look out the windows – and this is our normal, simplistic approach – “It’s not raining, what on earth’s happening?”’ Ian Warsap, Black Sluice’s boss, told me. ‘And then the penny drops: there may be a big hole in the sea bank somewhere. And indeed there was.’

An eighty-metre section of the sea wall had crumbled at a place called Slippery Gowt, allowing the tide to rush in. RAF Chinook helicopters dropped aggregates into the gap, and a column of earth-moving equipment rushed to repair the damage. Nobody is sure exactly what caused the breach, apart from the surge tide, but one explanation gives a startling insight into the vulnerability of the English coastal defence system: animals, either badgers or rabbits. In Italy, flood engineers have a similar problem with porcupines. ‘There’s certain mammals of certain size that can dig themselves through banks, predominantly the banks that may have been constructed from the silt that’s within the river, so … it doesn’t have a lot of strength to it,’ Warsap said. ‘One will never actually know in that instance and I think people are very cautious about pointing a finger.’ He clearly didn’t want to be accused of slandering badgers. (Richard Austin, who went to Slippery Gowt the morning after the breach, said he’d seen rabbit holes, and added that they have a ‘badger problem’.) Warsap mentioned another possible trigger for the breach: the wake of a ship that came up the Haven on the storm tide, against the instructions of the Boston port master. The more you talk to flood experts, the more you realise the distinction between ‘overtopping’ and ‘breaching’ is not clear-cut. Adam Robinson, of the Boston barrier, said that in some places in 2013, the water had entered the town from underneath its defences, rather than over the top. Any flood bank made of earth, even in part, is vulnerable to animals burrowing or the dead root systems of old trees.

Angela Hatton, the oceanographer, had one optimistic forecast: scientists haven’t found reason to think that storm surges – unlike tropical storms – will become stronger or more frequent in the coming century. But there is consensus that, along with sea-level rise, rainstorms will become more intense and river flows could increase by a third. The greatest peril for Boston, and for London – with a correspondingly tiny chance of it happening – is for a river flood and a storm surge to hit simultaneously, in which case a barrier will avail us nothing. ‘The Boston barrier is not offering a guarantee you will not be flooded any more,’ Warsap said. ‘When somebody says there’s a one in a million chance of something happening you go “Pwah, it’s never going to happen.” But while there’s that one in one million, the risk is still there.’

The fields where the Quadrant was built didn’t flood in 2013, and they haven’t flooded since. Newton has remained true to his plans. Boston United is in its third season in the new stadium, the new road is open, and many of the houses have been built, including low-rent homes purchased by a local housing association. Houses built after 2009 aren’t eligible for the national scheme that pools insurance risk for houses in flood-prone areas, but insurance doesn’t seem to be a problem for houses that have never experienced a flood; I got quotes for two identical Chestnut houses on the market, one on the Quadrant and one on a development away from Flood Zone 3. The Quadrant quote came out slightly cheaper.

Like so much new private housing, the two-storey Chestnut houses are small and tightly packed, with small gardens. The quite ordinary late 20th-century houses neighbouring the Quadrant to the north occupy plots that would fit three or four of their new neighbours – house, garden, parking space and all. But the houses aren’t bad-looking, with their little flying porticos. The swales – deep scoops of ground intended to hold and gradually release rainwater into the drainage system – are pleasing, and a new house deserves a chance to weather and have trees grow up around it before it gets judged too harshly.

I walked along Wells Place, where Chestnut built a row of two-storey houses whose ground floors would be partly below water level in the baseline breach scenario the flood consultants worked from. The ground had been raised in such a way that a gentle ramp or steps rose from the road to a flood-proof door. If you were standing at the door, the water would probably come up to your knees. If you were on the road, you’d be in worse trouble. I talked to a few residents. One was angry about his house, but his anger didn’t really seem to be about the house; another, a pale Lithuanian woman with a faraway expression, said climate change and flooding was something I should talk to her son about when he came home from school. Another, the bracingly confident Karen, said the Chestnut sales rep had been quite upfront about anti-flood measures. Who didn’t know about flooding these days? It was just one of those things. She didn’t keep anything irreplaceable on the ground floor.

Companies and governments can plan a hundred years ahead, but it’s hard for individuals. I asked Roy Lobley, the avuncular flood consultant who designed the flood mitigation plan for the Quadrant and seems to know everyone in Lincolnshire, about the flood-proof doors. What would happen to them in fifty years, if there’d been no flood? Wouldn’t people just replace them with ordinary doors? ‘Well, here’s a good question,’ he said. ‘Who’s gone out to make sure that Chestnut Homes have actually put the floor in at that level or not?’ There’s no reason to think Chestnut didn’t; Newton wrote to me: ‘The floor levels HAVE been constructed to the levels established within the flood risk assessment and agreed with Boston borough council.’ But Lobley was making the point that nobody checks. Gildersleeves explained that the council doesn’t have the resources to make sure planning conditions are fulfilled; it only checks retrospectively, if something goes wrong.

Julie Foley, the EA’s director of flood risk strategy and national adaptation, told me that more than half England’s local planning authorities say they don’t check whether developers fulfil their promises when they build their projects. In the post-Grenfell era, this might have been shocking, but we’re now in the post-post-Grenfell era, where British public services are assumed to lack the resources to enforce anything. I asked Foley if the Boston barrier made it more reasonable to pursue new development in the area. Her response made me think of what the risk expert John Adams calls ‘risk compensation’, the idea that in an environment that’s been made safer for us, we naturally increase our risk-taking up to the point where we restore our level of riskiness to what we were comfortable with before the safety measures were put in place. ‘The public purse, and investments like the Boston barrier, will have been focused on protecting existing properties at flood risk, of which there’ll be a phenomenally high number, given it’s all in Flood Zone 3,’ she said. ‘If we start diverting lots of flood defence monies for new development, we’re providing a rather perverse incentive for people to ignore planning policy. To state the obvious, we’d basically be saying that government will come in and just build a flood defence to sort it out. And there isn’t always a flood defence solution. Our primary goal is to not have development in areas that are unsafe to flooding in the first place, rather than have the community think: “Well, it’s all right, because we’ll get government investment and the Environment Agency to build us a magical flood defence, to sort the problem out.”’

Given how grateful Boston was for the barrier, the level of exasperation towards the EA there, and in the neighbouring council of East Lindsey, is striking. Partly this comes down to a long-running battle between the councils and the EA over the vast fleet of static caravans on flood-prone land in and around Skegness. East Lindsey, which has responsibility for Skegness, wants people to be allowed to stay in their caravans well into winter; the EA deems this an unacceptable threat to human life. Partly it’s a feeling that the EA is only interested in houses, and doesn’t care about protecting Lincolnshire’s rich fields. ‘We’ve got the best and most fertile agricultural land in the country. To the Environment Agency that’s worthless, but to us, it’s billions of pounds,’ Gildersleeves said. ‘They obviously do a lot of calculations, how many houses there are, and they have so many points,’ Richard Austin said. ‘But an acre of prime farmland has very little weight in that calculation, which is wrong.’

The deeper resentment lies in the feeling that the EA, and other nannying metropolitan fusspots, want to kill growth in Boston. ‘It’s about my kids and their kids that might want to live here and grow up here,’ Gildersleeves said. ‘We’re about meeting the needs of that existing population plus the people that want to move here.’ Foley points out that councils, not the EA, decide what gets built where. ‘We’ll never know what happens afterwards when the development’s put in place. We’re not there if that development floods in the future. Somebody waves a piece of paper saying: “Well, the Environment Agency said it was OK.” That’s not really helpful to those communities, because we have no role to ensure it’s OK. That’s the role of the democratically elected local authority.’ As Roy Lobley pointed out, the EA made clear to the council that lifting its objection to the Quadrant didn’t mean it was happy with it. He and Chestnut ‘came up with [a way to make] the development safe. And I suppose we left it to the council to decide. The only way we could not increase the flood risk to other properties was not to raise the Quadrant. So, Mr Council, do you want this to happen here or not?’

Without development, Newton wrote to me, the communities of the Lincolnshire coast ‘will not thrive and prosper. It is possible, as with the development at the Quadrant … that development can take place whilst mitigating against future flood risk.’

I heard a lot of grumbling in Boston about new houses ‘sticking out like a sore thumb’ after being built on artificially raised ground. There are stories of plots in the middle of a row of houses where a new house ended up one or two metres higher than its neighbours. I never managed to find one, or I may have seen one without realising it, interpreting it not as a sore thumb but as a more interesting streetscape. The thing that sticks out in Boston is the Stump, its main landmark and tourist attraction. Perhaps what Boston needs is more sore thumbs.

Nationally, the way the government’s planning policy has played out is that the pretty downlands of the rich south-east have managed to use aesthetics to obstruct housebuilding, leaving the flood-prone lowlands of the east to take up the slack, often enthusiastically, but to the detriment of their long-term security. Before I went to Boston, it didn’t make sense to me that large housing developments were being built on land below high-tide level. As Hugh Ellis said, beyond the scrutiny of developments in zones of high flood risk lay a more troubling question: ‘What is the future of a city like Hull? Or what is the future of Skegness? Or Great Yarmouth? Or Boston?’

Having spent time in Lincolnshire, I see things a little differently. The risk is real and scary, but it is also clearer, and more manageable, than I thought. The danger for the foreseeable future is not of rivers and seas swamping Lincolnshire towns and villages and taking possession of them for ever. It’s that while the waters have inalienable visitation rights to the settlements of the Fens, land-dwellers have come to treat them as rude strangers to whom every door must be barred, rather than expected guests who must, every so often, be accommodated. Boston treats flooding as a threat to its growth plans, rather than an integral part of them; as a menace to be held at bay, rather than as a factor that could, by its assimilation into the architecture of a growing town, make it a more distinctive and remarkable place.

To be fair, Boston’s planners know this. I found that complaints over enforced sore-thumbism were often combined with doubts that developers would ever have the imagination, or take enough chance with their short-term profits, to design attractive, well-engineered, reasonably priced houses that would stand clear of the highest possible storm tide – houses on stilts, for instance, which, although they might not be right for Boston conditions, echo the stilts that Fenlanders once used to wade through the marshes. Someone who knows the Lincolnshire housing market well countered my impression that Chestnut Homes was taking Boston over by saying that the town was lucky to have found a developer with the will and resources to build a stadium and five hundred houses, when the big national housebuilders were much more likely to have their sights set on the considerable rewards that would come from winning a planning battle in Surrey or Hertfordshire.

I asked David Newton why Chestnut didn’t design houses with no ground floor living space, houses on stilts, houses with floating bases. He wrote back: ‘Selling prices are comparatively low in Boston and Lincolnshire compared to other parts of the UK, and build costs are high due to the piled foundations. Therefore, it is not viable to incorporate the measures suggested economically, and there is no need to do so as the risk has been mitigated.’ And yet there’s nothing to stop the councils of fenland Lincolnshire setting aside an area of land for architects, engineers and builders to create and market elegantly raised, flood-resistant houses, even setting national standards for this sort of building, in the way Orkney made itself a laboratory for wave power. Nor is there anything to stop them planning holistically, rather than development by development. ‘We’ll need some quite transformational approaches to development,’ Foley said. ‘If you want to build in certain areas, the floor levels are going to have to be much, much higher. And yes, you can’t just be thinking about that one specific development, you’ll have to think about all communities doing that and having a high standard.’

The Netherlands’ fortress mentality in respect of the sea is combined with its cities’ distinctive embrace of waterways and the country’s constant experimentation with water-related technology, from floating houses to flood control (the business end of the Boston barrier is Dutch-made). Without wanting to minimise the real dangers from climate change faced by the people of Venice, the tenor of reporting about the city over the past decades has emphasised flooding and de-emphasised the way the city manages the state of permanent flood that lends it such splendour and mystery.

It would be easy to caricature Richard Austin as a fortress builder – a bypass to keep out the traffic, a barrier to keep out the water, Brexit to keep out the Eastern Europeans – except that he didn’t vote for Brexit. He sees the arrival of immigrants as a part of a historical cycle. ‘I think the majority of people that voted just didn’t like the huge change that occurred in the town and sort of being swamped with, you know, half the population foreign nationals, they couldn’t hear English in the street any more and just felt strangers in their own town,’ he said. ‘It’ll need a generation for us to settle in together … Historically, this has happened time and time again in Boston.’ Historically, it has also happened that Boston lived with and by the water, rather than attempting to shut it out. And as staunchly as Alison Austin defended the Quadrant, she spoke wistfully of other possibilities. ‘It would be marvellous to have houses on stilts, yes,’ she said. ‘But I really don’t think the average builder has got the capacity.’

In The Draining of the Fens (2017), Eric Ash points out that neither the inland flood plains nor the coast have ever been static. Rivers have silted up and changed their course, barrier islands have vanished and storms have torn up the shoreline: a ‘line’ that has always been defined by a belt of mudflats, creeks and scoured-out hummocks of salt-tolerant plants, covered by water at the highest tide but usually above it. People have always found a niche in this landscape, and living there meant building dykes, mounds, ditches and causeways, trying to keep the sea at bay here, draining a bit of marsh there, finding a drier spot for houses and barns. ‘If “natural” is meant to imply the state of things before or without human involvement,’ Ash writes, ‘then for all intents and purposes there has never been a “natural” fenland, and indeed such a term is virtually meaningless.’

In the Middle Ages, the mud belt of the Wash was much further inland; Boston, which prospered from the wool trade, was close to the sea, and the eastern edge of the Quadrant site, where the stadium stands, was often under it. The farming and fishing villages, where malaria was endemic, depended on floods and tides, and suffered from them at their most extreme. In summer, livestock would graze on fresh grass, and in winter they would eat hay, while floods watered the rich soil. There were always fish, eels and wildfowl on the mudflats and in the reeds. An easily damaged tracery of skills, rights and mutual obligations was supposed to keep the water under control; often, it didn’t. From the beginning of the 17th century, sporadic efforts at drainage became more urgent and systematic. Bigger drains were dug and windmill-powered pumps brought in to create new arable fields. The old fenland way of life began to disappear, not without resistance. The name Black Sluice supposedly comes from the colour of one sluice gate after anti-drainage insurgents set fire to it. Now, the land is one great flat kitchen garden, as if the wetlands had never been.

One morning in November I got up in the early hours in a Travelodge in Wyberton, the hotel that was promised for the Quadrant site. I grabbed my coat and the cheap neoprene waders I’d bought online and after a short drive and a meet-up in a dark car park found myself tramping along behind DeWayne Cross, of the South Lincs Wildfowlers Club, on a path through Frampton Marsh. The stars glared; Orion hung fierce over the mouth of the Haven to our left. On the far side a cluster of white lights marked North Sea Camp, where Jeffrey Archer served his sentence for perjury.

Cross is fifty, a big, gently spoken man with a young dog. He loves the marsh. ‘I’ve not come so much this year, because my mum, as you know, my mum passed away. She’s had cancer and that, so she just passed away recently … Normally, if I’m in full swing, I’m down here three or four times a week, if not more. We have a bag limit of ten birds. But I would say out through the season, you’d probably get your bag limit three times, if that.’

The wildfowlers are on good terms with the RSPB. Cross shoots legal birds: wigeon, teal, mallard, shoveller, greylags, pink-footed goose, Canada goose. He’s been going to the marsh since he was eighteen, when Chris, the local gunsmith, first took him out. In those days he wore fireman’s boots, cut-off leggings and a longshoreman’s jacket. He got stuck in every creek he crossed. He lost a boot in the mud. An east wind was blowing, it was snowing and he couldn’t feel his hands. ‘That morning Chris picked off five different species of duck. He looked at me and said: “What do you reckon?” And I said: “Yeah, this is for me.”’

Something high and dense loomed up ahead of us in the darkness. It was the sea wall. We were very close to the point where AECOM had modelled the effects of a breach. We were in a nature reserve, but it was still tamed human land. On the far side was the wilderness. ‘There will be a lot of cow holes, where the cows have been, ’cause they do graze the marsh,’ Cross said. He warned me to step on the tussocks. ‘If you go in, you’ll probably go up over your knee.’

We climbed up the sea wall and down the other side. I tried to walk on the tussocks; in the beginning it was dry enough, but it soon became squelchy. The sea had covered the whole area up to the sea wall a few days earlier. There’d been a mild storm surge, and the Boston barrier had been closed for the first time. Cross led us out through an increasingly muddy marshscape. I shone a torch ahead to try to see the mudholes before I went into them. A couple of times he led us across small creeks: a scramble into the mud at the bottom and up the other side. I thought about climate refugees tens of thousands of years ago, trying to keep dry as Doggerland gradually slumped into what would become the North Sea. They wouldn’t have lacked food. As the darkness greyed, the marsh around us began to pipe and warble, each sound precise and distinct.

Teal or mallard is best to eat, Cross says. ‘What I shoot, I live off. I have done since I started. When I say I live off the Wash, I literally live off the Wash. We make everything. We have a lot of geese meat, we do burgers, sausages, spaghetti Bolognese, chilli. Nothing goes to waste.’

‘What do you do with the feathers?’

‘I take them to the local abattoir.’

‘And what do they do with them?’

‘They go to a rendering plant.’

Cross and his wife have four children of their own and the guardianship of two others. His eight-year-old female ward is keener on shooting than his 11-year-old male ward; he takes her out on the marsh with him. They’re all used to eating game. ‘I find if you make everything into burgers and sausages they will eat it.’

We reached the place Cross had chosen to shoot from. We lay down on a dry, raised area of wiry grass, looking down on a broad creek with a few puddles along the bottom. The sun wasn’t far below the horizon. I could hear curlews. A few birds were in flight, outlined against the orange band and narrow grey clouds at the edge of the world. ‘I can tell by the wingbeats and the silhouettes what they are. For a beginner it can be very difficult because your mallard and your shelduck fly the same. But the wingbeats are different. Over the years I’ve learned that. I like birdwatching as well. Some people don’t understand that shooting and conservation goes together.’

Watch a short film of James Meek going wildfowling with DeWayne Cross in 2021, when he was researching this piece.

Some redshanks flew over shrilly. There were shots in the distance. One of Cross’s friends was working another part of the marsh. Cross raised his shotgun and, with three shots, dropped three widgeons. It was his only bag of the day. He found one bird and spent a long time trying to get his dog to climb the steep far bank of the creek to look for the others. His best dog had died not long before; it had been a bad year. In the end, Cross and the new dog found all three widgeons, their black eyes still bright and open, their chocolate heads turned to the side. The mud of the marsh dries black.

‘It’s about seeing the sunrise, it’s about seeing the marsh coming to life. You don’t see these sights laid in bed, do you? Those people that lay in bed till dinnertime. They don’t see nothing like this.’ The sun was up and the creek was filling fast, gurgling as it rose. Cross talked about the cryptic, changing geography of the salt marsh: the shifting course of the creeks, Duck Island, which silted up and isn’t an island any more, and another island where all the feathers gather in the reeds on an easterly wind. ‘Each year the tides are getting larger. Never, never underestimate the tide. It’ll always fill in behind you. A northerly wind’ll always push it up this side of the Wash. Years ago, we had a northerly wind, and we was right out the front, wildfowling. I’ll never forget, there was an eighteen-inch wall of water just coming off the top of the flood wall, just rolling over the top. We had to get our gear and quickly run for it. Once you start walking in tidal water out there, you struggle to stand up, because of the current and the force of the water.’

I asked him about the 2013 storm. His house is close to the marsh; he’d seen the sea come level with the top of the bank. ‘I’d seen them come hard before but never that hard.’ I also asked him about the Quadrant. He told me one of his grown-up daughters had tried to buy several houses on new developments, but they’d all been snapped up before they were built. ‘You can’t stop the growth of the population, can you? The only thing I disagree with is taking land that’s producing food for the country out of production and building houses on it.’

Cross remembered his childhood on the wild side of the sea wall, sliding on the mud of the creek banks, dodging dive-bombing birds protecting their nests. He went eeling with his friends. ‘Chris’s grandad used to love eels. “Do you want some, boy?” It wa’n’t for me.’ I asked if he could introduce me to Chris, but it wasn’t possible. Chris was in Lithuania. ‘He’s bought some property out there. And a bit of land.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.