What I most wanted was a SodaStream. A person with a SodaStream was in charge of his destiny to a pretty awesome degree. Same with the Breville sandwich toaster. Instead of a slice of Scottish Pride smeared in beef paste, you could go your own way, killing it softly, taking over the kitchen and incinerating a few squares of plastic cheese and a bit of ham in a sarcophagus before hitting the street like the god of modernity. Guys like that had lava lamps. They had a Casio calculator with trig functions in their schoolbag. These items remain, but with other things, the sense of lost desire can be strong. The future is always behind us, or at least it seemed that way in the days of the space shuttle and the BBC Micro: they could memorably explode or freeze in the middle of the day, reminding us of the relation between obsolescence and novelty.

Growing up, I worried I didn’t have the requisite gear with which to launch myself as a leader of tomorrow’s people. I set great store by the small things I did have – a tape recorder, a digital watch – though I worried that Kafka probably didn’t have a gonk pencil-topper with crazy hands jiggling under his chin when he was writing The Castle. Then, about 1980, things took a definite turn towards the sun, and some saviour presented me with both a Sony Walkman and an Atari home video unit, made for people who were winning so big that the rest of the world would surely spend eternity catching up.

My mum died recently, and I realised, in the middle of it all, that a special world of technophobia had gone with her. She didn’t know what the internet was. She had never sent or received an email. Her phone, devious and self-involved, was an instrument of torture to her: making promises it couldn’t keep; showing caring messages covered in love hearts that instantly disappeared, never to be found again; lighting up, at all times of day and night, with graphics and noises only her grandchildren could decipher. Every day was a digital Golgotha. She felt scourged by technological advances and nostalgic for simple things that didn’t work. The big cupboard in her hall was like outer space, a cosmos indoors, full of junk and old gadgetry floating through time, dead appliances that still hinted at their powers of improvement. I felt she was keeping them for a happier domestic life in the next world, or for the past to return in this one, shaking us out of our need for better radios.

She called one day to ask me to stop sending nice pictures of my holidays to her friend Mary who lived up the road.

‘Eh? But I didn’t.’

‘Yes, you did. Mary knows all about your time in Mexico –’

‘New Mexico.’

‘Wherever. She has photos of you all in a hotel. Or in a pool. How do you think that makes me feel, that you send her pictures and not me?’

‘It’s called Instagram, mum.’

‘I don’t know what it is, but they should ban it.’

Another time, she complained that the woman next door had more TV channels than her. ‘That’s because she’s got a Smart TV, mum,’ my brother said. ‘We could get you one and you’d have all the channels you want.’ The following week it was all set up and Gerry was showing her how to use the remote control. He told her that she could pause the TV while watching Coronation Street to go and make a cup of tea. ‘Oh, I wouldn’t do that,’ she said.

‘Why not?’

‘Because what about all the other people?’

She thought she would be pausing Coronation Street for the whole nation. And the funny thing was that none of it was affectation; she genuinely felt the 21st century was a leisurely joke at her expense. She accepted that items existed – hair tongs, for example, or kettles that turned themselves off – which made life a bit better than it used to be, but these things were unusual. Most things were expensive and drove you mad. Existence, for our mum, wasn’t about change, it was about everything staying the same, and people too. She loved paying for things with cash, and, when she got a bank card, insisted on keeping it in the purse with her pin number.

She believed, with justification, that young people use material things to fool themselves into thinking they’re living their best life. (‘You can’t take it with you!’ was one of her favourite phrases.) If you’re eighteen now, obsolescence just tells you how much you’ve grown. Nobody with an iPhone13 secretly craves an iPhone6, not even for reasons of nostalgia or perversity. Consumers can enjoy things looking old – take the Roberts radio craze – as long as the item has digital capability. But there is a limbo zone of deleted desires, of superseded dreams, that operates a bit like Proust’s writing on our sentimental credulity.

Extinct takes the long and often absurdist view. There are mad things we don’t miss – arsenic wallpaper (vivid but deadly) – and things we miss every twenty minutes: ashtrays (deadly but vivid). ‘In extinction,’ Thomas McQuillan writes about Concorde, ‘it’s not the objects that fail. It’s the world that supported them that has gone.’ That is certainly true about supersonic flight. I suppose some people in the UK would still like to get to New York in three hours, but when the means of fulfilling that desire becomes defunct, where are you stranded? Concorde was a gas-guzzler, and too expensive. Most of the people who used it are flying around the world on private jets. But, even as an ordinary punter, you can regret Concorde’s failure: it was so beautiful, and its forced ending (after a crash) made it the Hindenburg of my generation. To judge from a rash of recent novels, young people believe that, in the past, we were all just waiting for the internet: we weren’t, and life was quite nice without it, partly because it was calming to know certain things were unavailable, and sane-making to know that the journey towards what you fancied might be quite long, and you might meet people along the way, and you might never even get there. I love the internet, perhaps more than anyone, but my innocence died with its success.

For Lydia Kallipoliti, self-mirroring was there all along in the new things we chose to invest in and build. ‘Rather than operating autonomously’, she writes in Extinct, Cybernetic Anthropomorphic Machines were ‘mechanical replicas of the “master” human operator, echoing their movements in an act of orchestrated puppeteering’. History is littered with defunct machines that were meant to better us, in more senses than one. The American engineer Ralph Mosher, we learn, ‘introduced additional features to make [robots] more lifelike and to give them a capacity for error, typical of human actions’. To this end, he worked on machines that were tied to the human nervous system, to replicate the logic of hesitation. Mosher envisioned the human-machine union – our neurons ‘translating desire into kinesis’. This reminded me of my one-time friends in WikiLeaks, lashed all night to their laptops, their nervous systems wired into these machines that they believed contained their conscience.

The future wants to look like a Stanley Kubrick set, but ends up happening next to an Aga. The ambience of futurity never becomes extinct, though, even when its talismanic objects disappear. As Guang Yu Ren and Edward Denison put it, ‘there are some things for which extinction is a mere blip in a broader existential experience that long outlives the subject’s original function.’ I can still recall the strange, shifting sound of the fax machine in the old LRB office, the way it would suddenly begin scrolling out possible futures. ‘Yes, why not?’ from Susan Sontag. A blast of rage from Harold Pinter. A request from Hitchens and a poem by Heaney. They’ve now got Seamus’s fax machine behind glass in his hometown museum in Bellaghy, and, when I saw it the other day, I recalled the squeal and purr it would cause in Tavistock Square, setting off our grey machine linked to the stars.

As a boy photographer, I had a special love affair with the Kodak Flashcube. I still see it in dreams, the button on the camera depressed by a sticky finger on Christmas morning and ‘pop!’ – instant history delivered in a tiny miasma of burning plastic and knackered filament, a shock but an upgrade on available light. ‘Its fragility disguised its ferocity,’ Harriet Harriss writes in one of the best essays here. ‘Partnered with Kodak’s Instamatic camera, the Flashcube’s adaptability, portability and ease of use made interior photography possible for the masses … The impact on interior behaviour as well as interior spaces was substantial … In the Flashcube’s dazzling light, families staged domestic tableaux in an effort to display their nuclear family credentials.’

Nuclear is right: the bulbs could cause first degree burns. And the light couldn’t be controlled, not quite, so a radiation red would often fill startled eyes in the snaps. ‘If they ever looked at the used Flashcube before discarding it,’ Harriss writes, ‘subjects would have noticed the scorch marks inside, resembling the remnants of a chip-pan fire in a doll’s house.’ Which brings us to Ibsen, the poet laureate of the never-quite-extinct. Everyone knows that feeling at four o’clock in the morning when you’re suddenly unsure what any of the family’s belongings have to do with you. It can add to the grief. ‘It’s not only what we have inherited from our father and mother that walks in us,’ Ibsen wrote. ‘It’s all sorts of dead ideas, and lifeless old beliefs, and so forth. They have no vitality, but they cling to us all the same, and we can’t get rid of them.’

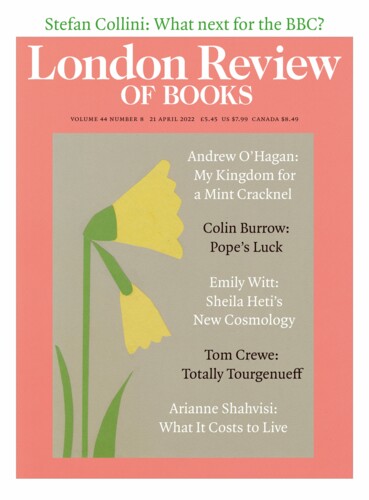

Consider the snail. ‘Snails are on the front line of extinction these days,’ Richard Taws writes, and it’s not just their stuff or their parents, but their existence as a species. Achatinella apexfulva, the Hawaiian tree snail, gave up the ghost on 1 January 2019. Maybe the loss of a few Fisher Price toys from the marketplace isn’t so bad. But humans can long for things they never wanted very badly in the first place. I yearn every other day for Mint Cracknel, a chocolate bar from the 1970s that was criminally discontinued. I miss Player’s Number 6. I mourn flappy airline tickets with your name printed in purple ink. On busy, productive days, I can still hear the compressed suck and thunk of the pneumatic postal system that sent mail from floor to floor in the office job I had when I was sixteen. I miss memos. I crave the Polaroid SX-70 – ‘seeing the image take shape produced an overwhelming urge to see and hear the magic repeated,’ Deyan Sudjic writes – and I wish I had a serving hatch in my sitting room because then I’d feel properly middle class. Only yesterday, I debated with myself whether to buy a telephone table and set it up in the hall with a red telephone, like the one we had in 1977, the one that never rang until one day it did. My mother had got it connected while we were all at school, and I can hear it ringing still.

So many of the deleted objects were to do with voice. You spoke into them, or they spoke back, or you rolled paper into them and clacked, finding something to say. A suitcase was found at my mother’s house. It was full of my college essays, and, sandwiched between the folders, home cassettes of my favourite albums. I had pressed stop, some time in 1990, on each of those tapes, and here they were, frozen mid-song, 32 years after I’d gone, and the bands had gone, and the machines that played the tapes had gone too. Yet nothing seemed more alive to me that week than the contents of the cupboard where the suitcase had been found. I hoped that maybe there would be an old ITT cassette-player at the back, dusty and perfect. If you pressed the green button it would light up with the words ‘Batt OK’.

Listen to Andrew O'Hagan discuss this piece with Thomas Jones on the LRB Podcast.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.