Albrecht Dürer arrived in Antwerp in August 1520. The journey from his home in Nuremberg had taken just under a month and he had recorded it in his journal. His main concern was to itemise his expenses. No expenditure was too small to note: ‘Ten pence for a roast chicken … I paid one stuiver for a pair of short socks.’ The meticulousness we associate with Dürer’s art also extended to his personal recordkeeping.

In Antwerp he mixed with a cosmopolitan crowd. An early entry records a dinner with ‘the Portuguese’: João Brandão, the king of Portugal’s factor in Antwerp, and his principal secretary, Rodrigo Fernandes de Almada. They became regular dining companions; gifts followed. Within a month of their meeting, de Almada sent Dürer ‘a cask of preserved sweets … barley sugar, marzipan … and quite a lot of sugar canes, just as they were harvested’. There were further tokens, including feathers imported from Kozhikode in Kerala, unseasonal peaches, silk, ‘six Indian nuts’ (coconuts) and ‘a little green parakeet’ for Dürer’s wife, Agnes. These were the tastes and trappings of global trade – the sugar probably came from slave plantations in Madeira.

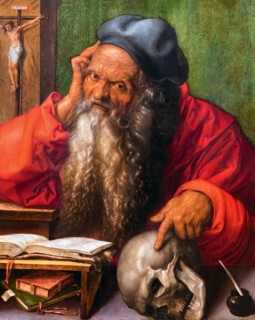

In return, Dürer gave de Almada books of his woodcuts and some of his most famous engravings, including Adam and Eve, Melencolia I and St Jerome in His Study. It was an effective strategy: de Almada commissioned Dürer to paint his portrait. At some point in March or April 1521, as he prepared to return home, Dürer presented de Almada with his most generous gift: ‘I painted a Jerome in oils, taking care over it, and gave it to Rodrigo the Portuguese.’ The painting usually hangs at the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga in Lisbon, but is currently on display in Dürer’s Journeys: Travels of a Renaissance Artist at the National Gallery (until 27 February). Dürer depicted Jerome repeatedly throughout his career, and across different media, but his painting for de Almada was a departure. The earlier images show Jerome at work in his study, or as a penitent in the wilderness, beating his breast with a rock. In a panel from around 1495, held by the National and included in the show, Jerome is a small figure in a rocky, forested landscape. In the foreground a pair of finches appear amid carefully individuated plants. The famous engraving of St Jerome in His Study from 1514 (also on display) shows Dürer at the height of his powers, performing a kind of alchemy on the copper plate: he coaxes it into producing golden light, streaming through a mullioned window; grainy wood; fluffy lion fur. Jerome is – again – a small figure, his head bent over his work. His study is a delight for anyone with a stationery fetish. Neatly folded letters and a pair of scissors are tucked into a holder pinned to the wall behind him. This is a portrait of Jerome’s study as much as a portrait of Jerome.

In the Lisbon image, however, we are brought up close. In his preparatory sketch, for which Dürer used a 93-year-old model, Jerome was again shown looking down. But in the painting, he gazes out towards the viewer with an expression somewhere between fatigue and suspicion. The open book on the reading stand has a soft cloth cover, which has been tucked into the pages to mark a place. Jerome’s index finger points to a skull, turned on its side. There is dirt under the nail. Dürer is the master of the minute: fingernail dirt has rarely looked so compelling. I wonder if it’s the ink-dirt of scholarly labour or dirt from the wilderness. Or maybe dirt from stroking the lion’s fur? This is a fleshier and more human portrait of Jerome: wrinkled, bearded and grubby-fingered. Jerome was an icon and exemplar for Renaissance humanists, and elements in the painting nod to humanist ideas (the skull, for instance, might symbolise Erasmus’ concept of self-knowledge). The painting was a gift to a Roman Catholic, though, and may be, as the catalogue suggests, ‘a painted argument in their intellectual exchange of ideas’.

The volume of Dürer’s journals that describes his trip to Antwerp in 1520 is the only one that survives (in two 17th-century copies). We don’t know if there were other volumes. But in any case, it’s more of a ledger and Dürer rarely records his feelings, except in clipped terms: ‘I saw on the bridge where criminals are executed the two memorial figures set up to mark where a son chopped off his father’s head. Ghent is an attractive and remarkable city. Four great rivers flow through it.’ His feelings about the things he saw and the people he met can only be guessed at. We can’t know if he thought of de Almada as a friend or just business contact. And we don’t know if they corresponded after Dürer left Antwerp. De Almada’s last appearance in the journal records the ‘gift of one of the parrots they bring from Malacca’.

Dürer’s painting stayed in Antwerp until 1548, where it was fêted and much imitated. In the National Gallery’s show, it appears alongside several paintings produced in its image. It’s easy to see why it was popular – Dürer asks us to look into the eyes of the Church Father, close to death, contemplating his life and its labours. But behind it are the remains of a relationship, one measured out in the exchange of peaches, feathers, engravings, sugar, silk and ideas.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.