Many of the works in The Making of Rodin, currently on show at Tate Modern (until 21 November), are displayed on what look like the packing cases in which they arrived. A notice on the wall tells us that these supports, and the Perspex boxes containing the sculptures, will be reused in future exhibitions and in construction projects at the gallery. Exposing the hardware is a way of acknowledging the environmental cost of transporting and displaying art. It also catches the provisional mood of the past eighteen months. As a curatorial gambit, it’s in line with the objects these rough plinths support: Rodin swings between the ephemeral and the monumental, and many of the sculptures here were first displayed on little more than bare boards. Almost all of them are made of plaster, their fragility contrasting with the heavyweight bronze or marble forms into which some of them were later developed. The packing boxes show that these are objects on their way to somewhere else, or to becoming something else.

In 1900, as his celebrity boomed, Rodin organised a display of his work at the Place de l’Alma to coincide with the Exposition Universelle. A specially constructed pavilion with high arched windows, a glass ceiling and adjustable blinds showed the sculptures to great effect, allowing the play of natural light on their surfaces. Visitors were confronted with an all-encompassing whiteness, the fine dust of the studio filling the air. This was Rodin’s first one-man show in France, but he had posterity in mind: he called it his ‘museum’. The pavilion came down in 1901, but Rodin soon reprised the show at his home in Meudon, just outside Paris, where he had kept a studio since 1893. It is now the Musée Rodin, from which almost every work at the Tate has been loaned. Rodin bequeathed it all to the French state in 1916, the year before he died. The bequest established material genealogies for each of his ‘finished’ sculptures; it also helped to produce a shift in taste towards the more provisional objects Rodin made in advance, which gradually came to be seen as artworks in their own right.

Plaster, with its preparatory or partial quality, had a particular appeal in the decades after the First World War. And it’s this that makes Rodin seem so modern, almost one of our contemporaries. Lighter, more playful, and alert to accidents of making, the plaster sculptures are closer to present-day aesthetics than the works in bronze. These are part-objects, remodelled, transformed, transitioning. The artist Phyllida Barlow compares plaster’s paradoxical combination of substance and transience to that of snow. Yet in the 1900 show, from which the Tate exhibition takes its cue, Rodin exercised an unusual degree of control over the work’s display. He chose each piece and its socle, and by crowding them together to suggest the artist’s studio – or an aestheticised and tidied-up version of it – he appeared to offer real access to his process. Rodin would have approved of the current exhibition. Blinded by whiteness, we approach the assembled limbs and contorted faces ready to relearn old lessons about transcendent material transformation.

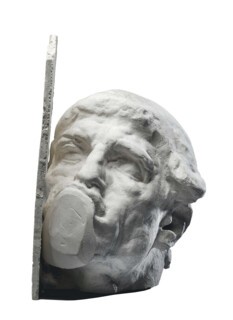

One of the first works in the show is both familiar and very strange. The head of The Thinker, detached and upright, has its right side pressed to a plaster surface, into which a hole has been cut to reveal the ear. The fist on which the chin will later rest is here just a rude plaster plug, blocking and silencing the mouth. It’s a remarkable object, radiating violence. There are echoes of Duchamp’s With My Tongue in My Cheek, but the shock comes from something far more direct: a severed head, the stuffed mouth a final humiliation. One of Rodin’s talents was to let you see the brutality of making sculpture.

Later in the exhibition, a series of sculptural masks of Hanako, a Japanese actor and dancer known for her depictions of male suicide rituals, become harder to look at with every iteration. Rodin met Hanako at the Exposition coloniale de Marseille in 1906, and there are more images of her in the Musée Rodin than of any other sitter. He set out to capture her look of anguish, and in the process recorded the effort of holding her expression for the time it took to make the masks. Rodin’s empathic fascination with the body in crisis – combined with a conspicuous sadism – runs through the Tate show. It’s especially apparent in The Burghers of Calais: six figures, huddled and all too human, nooses around their necks.

‘Preparatory’ isn’t the best way to describe Rodin’s plaster works. He modelled mainly in clay and terracotta, before casting in plaster to make the object more durable. Some pieces were later cast in bronze or chiselled in marble. The plaster models were collaborative, the work shared between artist, caster and founder – with Rodin’s name inevitably taking precedence. Displaying plaster sculpture wasn’t unusual, but for Rodin it was more than a placeholder for a permanent sculpture to follow. He was registering the idiosyncrasies of the hand, forming a signature of sorts. He liked to save all the stages that led to a completed work, the accidents and contingencies of the materials and the studio. Photography played a part in this process, as a means of fixing each chance combination, and of making new combinations too. Some of the photographs – Eugène Druet’s Clenched Hand series, for instance – now seem inseparable from the sculptures themselves.

There are hands everywhere. Rodin made thousands of them, lined up in drawers, ready to find their way into one work or another, or maybe not. Resisting any attempt to connect them to a ‘finished’ work, they belong to no particular sculpture. Rodin called his loose hands, heads, arms and legs abattis (‘giblets’). An interesting choice of word: insides as outsides, objects for thinking as well as doing. Critics noticed the similarity between the abattis and the anatomical bits and pieces of the dissection room (as Natasha Ruiz-Gómez points out in the catalogue, Rodin made drawings at pathological anatomy museums when he was a student).

Elsewhere, bodies come into and out of focus, appearing at different scales and with differing intensities. Balzac turns up as the brooding monolith familiar from the finished bronze, but also as a corpulent power-posing nude whose genitals morph into a torrent of brown-coated plaster. Sometimes we just get his legs, sometimes the head, the marks of the mould still visible. In one version Rodin evacuated Balzac’s body entirely: a ghostly dressing gown, rigid with plaster, contains nothing more than the empty space where the man should be. Only the toes of a broken left foot poke out from under the hem of the gown. Rodin never lets us forget that fabrication is a matter of will – especially when it comes to his female subjects. The plaster slip that forms a spooky veil over the face of Hélène de Nostitz softens the marks of its making, leaving just a few lines of the mould around her chin. Air bubbles in the slip bring a note of chance to an otherwise highly controlled experimental object. The pencil sketches and notes on the surface of the plaster imply contingency but were in fact meticulously managed.

These visible traces of making also mark time. This is perhaps most overt where Rodin combined, rotated and repurposed body parts in surprising and anachronistic configurations. The left hand of Pierre de Wissant, from The Burghers of Calais, creeps from the side of Camille Claudel’s scarred and spattered head. Scale is blown wildly out of joint, as miniature figures cower beneath colossal body parts, articulated in ways that make no sense. In some assemblages, nude plaster figures – contorted and distorted – emerge from the Merovingian and Etruscan vases that Rodin collected. Rilke called the revenant inhabitants of these adapted found objects ‘small floral souls’. They seem to want to say something about the historical quality of plaster’s transitory nature, its ability to change the things around it and sometimes, too, its capacity to survive.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.