Jane Eyre, a series of large-scale lithographs made by Paula Rego in 2001, begins with two images based on the novel’s first scene. Girl Reading at Window is a more or less direct illustration of events, sequential moments laid out on a single page like a storyboard or graphic novel. Loving Bewick, the second image, is different. Its subject is what happens at that point in Jane’s mind, and what was happening in Rego’s mind. In the novel, Jane retreats behind a curtain to read Bewick’s History of British Birds. Her imagination, we understand, has grown to equal the brutality of her everyday life. As she reads of ‘bleak shores’ and ‘death-white realms’, the illustrated birds take flight. She forms of these places ‘an idea of my own: shadowy, like all the half-comprehended notions that float dim through children’s brains, but strangely impressive’.

In Rego’s hands this communion with Bewick becomes a Leda story: a pelican comes to life in Jane’s lap, its enormous beak hovering at the edge of her open mouth. She is older than the Jane of the novel, and the bird is gigantic. Her knees, covered by a dress of criss-crossed taffeta, are shaped like the ‘solitary rocks’ that Bewick says are ‘the haunts of sea-fowl’. The symbolism is of sacrifice or nurture – the pelican (not the first in Rego’s work) pierces its breast to feed its young – but the dynamic is sexual. The girl and bird are posed at an angle. Jane’s eyes are closed and her mouth stretched wide; she is needy, greedy, pained or ecstatic, the embrace a nightmare of assault or a dream of sustenance, perhaps salvation. Jane is fed by a fiction and so, in turn, is Rego.

By the time Rego came to make this lithograph, the ideas informing it had already found precedents in her work. In 1996 she experimented with a girl swallowing a stork, a print too spiky and direct to be suggestive. The etching Baa, Baa, Black Sheep from 1989 was an early flirtation with a feral lover, and in 1990 she depicted Andromeda dismissing a tiny Perseus and reaching up to caress the sea monster instead; in both of these images the woman’s face is hidden. Loving Bewick is in some sense the resolution of these earlier encounters between woman and creature: a more delicate balance, a more erotic proximity, a more drastic confidence. The lineaments, and the presence of monstrous fowl, recall an etching by Goya in the Caprichos, Is There No One to Untie Us?, which shows a human couple bound together with rope, the woman struggling as she is attacked by an owl her own size. Rego saw the sex in this and transferred it to the raptor. (Unlike the other images, Loving Bewick was made on a piece of transfer paper that her collaborator, the printmaker Stanley Jones, had kept in a drawer for three decades. ‘We haven’t had such a good transfer in years,’ he said later.)

The current retrospective at Tate Britain (until 24 October) shows – in its scale, its curatorial arc and its popularity – what should never have been in doubt: Rego’s unending ideas, her technical gifts, the fierceness of her intentions, her significance as an artist. She has often said she is not a ‘proper artist’ because proper artists paint in oils. Having grown up in Portugal, the daughter of liberal anglophiles living under Salazar, she was sent to finishing school in the UK and then to the Slade, where she met a number of ‘proper artists’ – one of whom, Victor Willing, she later married. The director of the Slade was William Coldstream, whose work was associated with the anaemic realism of the Euston Road School, and Willing’s paintings – which included wan female nudes in oils – weren’t out of place. Willing would become the star, and the critical voice, of their generation. Rego sat at the back of the class and painted from her imagination. ‘Of course one becomes very self-conscious at art school,’ she told her son hesitantly during an interview in 2016, ‘being a day-girl, not being an intellectual, the restricted way of teaching in those days – the Euston Road method, which I could not do. You lose your – it’s not so much your confidence you lose, you lose your – you hide more.’

The first two rooms at Tate show a painter with lots to say who is suspicious of the available means to say them. The opening work, Interrogation, was painted in Portugal when Rego was fifteen. A woman is flanked by two men in white, her head in her hand and her legs twisting around each other as she sits and submits. From this early figuration Rego drifted into abstracts and antic collages, her political rage apparently undimmed, her vehemence exerted with colour and scissors, but none of that work formulated a full response to the work of her heroes – Picasso, Dubuffet, Max Ernst, Arthur Rackham, Gustave Doré. The work most indicative of things to come is a painting for which she received a prize at the Slade, Under Milk Wood (1954), which transposes to a Portuguese kitchen Dylan Thomas’s (then new) radio play. Creatures dead and alive; expressive female figures; the heft of muscle and flesh; the invitation to interpret the scene as a psychosocial drama; homecoming as a crucible for storytelling: Rego would develop these and allied elements, but not for many years.

Rego and Willing met at a house party, sometime around the coronation of Elizabeth II. He was behind her on the stairs, and guided her into a bedroom. ‘Take down your knickers,’ he said. It didn’t occur to Rego to refuse. ‘I was a virgin, so you can imagine the mess,’ she told their son. ‘He could at least have hailed me a taxi.’ After a number of backstreet abortions, she decided to keep her next baby, then kept two more. She moved back to Portugal. Willing eventually left his wife and joined her.

Rego found motherhood false. ‘It was brush or baby,’ she explained. ‘When you were doing a picture you were much more yourself.’ Willing, meanwhile, became the arbiter of these pictures. He guided her and wrote about her, at times positioning himself as an art-critical bystander to her life. ‘It happened that when the picture had reached an impasse, the security of the family was threatened by a girl,’ he wrote in an essay about Rego’s work in 1971. ‘The artist introduced this girl in the dark, heavy, reclining form pressing into the top of the picture. An angry hour’s work … forced the picture to a conclusion.’ The act he describes is his own infidelity.

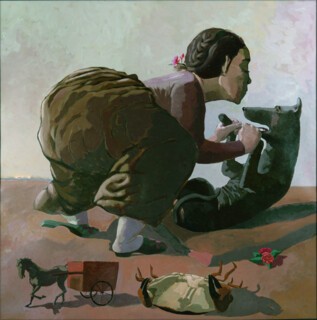

Willing was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1966. For the rest of that decade and all of the next, Rego felt she was ‘treading water’. In the early 1980s she experimented with large, unbridled paintings of almost comic-book violence, featuring a recurring character, Red Monkey. A few years later, after she’d seen the work of the so-called outsider artist Henry Darger, she riffed on his schoolgirl characters, the ‘Vivian girls’, in frantically populated acrylics. As Willing’s health deteriorated, she acquired focus: the cartoon figures crystallised into a series of paintings of an oversized young girl looking after a large dog. The girl is caring, taunting, playful and dangerous by turns, the balance of power firmly in her favour. She feeds the dog, lifts her skirt for him, adjusts his collar, shaves him with a lethal-looking razorblade. This girl and her doubles would recur in works to come. The dog, Rego never hesitated to say, was Willing.

The girl and dog paintings were exhibited at the Edward Totah Gallery in London, and met with critical success. Willing wrote the catalogue essay. In the eighteen months that followed, Rego worked on a sequence of large acrylics that became the culmination of a solo show at the Serpentine Gallery and which changed her career. Willing was bedbound. In Secrets and Stories, the documentary about Rego made by their son, Nick Willing, she describes bringing each painting-in-progress to the room where Willing lay, and asking him what she should do with it. His edicts were, in her account, unwavering. ‘Paint it all out,’ he’d say of something she’d just painted in. ‘You’ve got some beautifully painted figures there, and you’ve got rubbish furniture behind – it’s killing the picture.’ ‘He could see and I couldn’t,’ she said later.

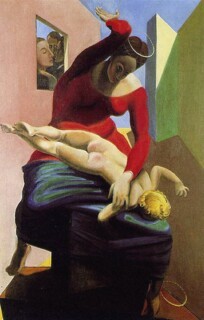

Many of these pictures, first shown in October 1988, are brought together at the Tate in a single room, the largest by far in the exhibition, reflecting their impact at the time. Everything before seems to lead up to this moment. The Policeman’s Daughter, Snare, The Little Murderess, The Cadet and His Sister and The Family all owe a debt to Max Ernst’s The Virgin Spanking the Christ Child (1926). Rego later told Fiona Bradley, the author of an excellent monograph on her, that Ernst’s painting was her favourite artwork. If you conceive of art history as a series of archetypes rather than precedents, Rego had begun to find a way to exploit them for her own purposes, just as the oral tradition of fairy tales invites retellings. The rounded faces of Picasso circa 1906, the spooky architecture of a de Chirico set, digressions on Las Meninas: Rego took all of this and turned it into a story about (in Willing’s words) ‘rebellion and domination; or freedom and repression; suffocation and escape’. The paintings are flat and spare: missives from a child’s world, perhaps, and all the more perverse for importing these games into the world of adults. There were ominous girls: wrestling with a dog, polishing a man’s boot, plucking a dead goose, approaching someone offstage with a ribbon, ready to strangle. And there were girls in groups – undressing a father, combing an older woman’s hair, tying a brother’s shoelace – the agency always theirs, each scene arranged theatrically for manipulation or harm. By the time the show opened, Rego was 53 and Willing had been dead five months. On the morning of his death, their three grown-up children, asleep on the floor in other rooms of the flat, were woken by a howl of fury from their mother. ‘Who is going to help me with my work now?’

In 1799, Goya published an announcement in a Madrid newspaper about the Caprichos, his first major series of etchings. He was 53. The eighty prints were works of the imagination, he wrote, and as such deserved more esteem than images drawn from nature, since the artist ‘has to put before the eyes of the public forms and poses which have existed previously in the darkness and confusion of an irrational mind, or one which is beset by uncontrolled passion’. Goya had survived an illness that had nearly killed him and had left him deaf. The etchings he made in the years after his recovery were as far as darkness could take him from his work as painter to the Spanish court. In the process, he transformed the medium of etching itself.

An etching is made by drawing on a coated metal plate using a needle. When exposed to acid, these uncoated lines are ‘bitten’ away, leaving grooves which hold the ink. The subsequent process of shading the drawing is called aquatint. The artist works from the most pale tones to the most dark in a series of layers, each of which is fixed with resin dust. In Goya’s time aquatint had been used in England and France, but solely for the purposes of reproduction: it was a way to make prints look like watercolours, preparing the drawing for hand-tinting. Goya saw the potential for aquatint to be an end in itself, a means of making nightmares: witches sitting in the penumbra; monsters erupting from the night; the Inquisition gathered under an intractable veil of grey.

Rego had worked with the printmaker Paul Coldwell in 1987 but it was not until two years later, after Willing’s death, that they began a major collaboration lasting for many years. (Her other significant collaboration, with her model, Lila Nunes, also began around the time of Willing’s death: Nunes was his nurse.) The first full series Rego made in Coldwell’s studio, Nursery Rhymes, was a direct descendant of Goya’s Caprichos, and established her graphic capabilities. Like Goya, she relied on her imagination, informed by years of drawing the human figure. Giant dolls dance with soldiers in Polly, Put the Kettle On. Faint courtiers emerge from mist in Sing a Song of Sixpence, as blackbirds gather at the king’s feet, ready to swarm. A giant humanoid spider holds Little Miss Muffet in a many-legged embrace. Here, the sly humour already evident in Rego’s work found expression in technical wit: the line drawings loose and free-associative, the aquatint masterfully calculated. The Nursery Rhymes are smart in the way a chess move might be, or a football trick, and just as stylish.

Coldwell had set up a press in a small room next to his kitchen in Hackney so that he and his wife, Charlotte Hodes (a former student of Rego), could make their own prints. He didn’t have all the right equipment to begin with but this suited Rego just fine: it became, in Coldwell’s words, an informal, secret location where she could experiment without interruption. She would arrive in the morning with croissants and the copper plates she had drawn on in the night, and they would begin. Over a period of four or five months, Rego worked feverishly, juggling several etching plates at a time, each at a different stage of development. ‘Everything that had been squashed in … came pouring out,’ she said. Coldwell had to keep track of timings and acid strength and where Rego was up to in her tonal gradation. He likened the print room to a pizza parlour and later wrote that this outpouring ‘was at times almost terrifying’.

While some artists make prints as commercial vehicles for their primary work, Rego has always treated the medium as the work’s full expression. Excepting her abortion series, where she made smaller prints of the large pastel drawings in order to disseminate them more widely (in the hope of encouraging Portuguese voters to turn up to a second referendum on the legalisation of abortion), Rego has never made prints as versions of or sketches towards something else. They are independent works. This doesn’t mean they are necessarily predetermined: their purpose has often been to set her free. ‘Whenever I got stuck or didn’t know what to do, I would make a print,’ she told the curator Sophie Lindo. ‘The process would free up my mind and let me just work without making art. Often that’s when you do your best things.’ The prints are not only a major component of her output as a whole – T.G. Rosenthal’s catalogue raisonné of her Complete Graphic Work contains almost three hundred – but sidelong views onto her habits of thought. They whisper something to the viewer; something like, as Marina Warner has put it, ‘This is what I know; this is what you – we – choose not to see.’

This summer a small exhibition of Rego’s prints was held at the Cristea Roberts gallery to coincide with the Tate show. It contained a few prints that were proofed by Rego and Coldwell years ago but never editioned. The commercial drive to treat them as finished works is obvious, but some are interesting precisely because they are unfinished – the first or last etchings of different sequences, either warming up or figuring out how to end. Procession to the Sea was made in 1996, after the last of Rego’s work on The Children’s Crusade, a series of etchings hand-coloured by Hodes. Procession is un-coloured and clearly unresolved. Unlike the other prints in the series, it has a wide landscape format, leaving space for several mini-scenes. A Joan of Arc-like girl makes an exit, gripping her horse with the balls of her feet; behind her a witchy monarch is carried on a litter by a group of gnarled children; there are twin blind women at the rear, dancers on the sidelines and, in the distance, a pair of angels at sea, negotiating half-drawn waves. There is more blank space here than Rego would usually allow. The plate is patchy and scratched in places, and the shadows are unnaturalistic, falling differently on different groups of people, as if she were trying out types of shade rather than capturing the fall of light. Yet – or perhaps because of this – it is full of strength and mystery, a portrait of Rego’s by now elaborately agile mind.

After 1989, when prints became a significant form for her, Rego seems to have made her peace with drawing as a final gesture. Very much a proper or, rather, improper artist, she largely abandoned paint in favour of graphic media. In 1994 she took up pastels and wielded them like knives. She spoke of ‘punishment’ and ‘revenge’. From a distance in the gallery, these majestic works – Dog Woman, Angel, After Hogarth – look like oil paintings and hark back to Velázquez or Murillo: smudged darkened backgrounds, a murkier and more mature overall palette than that of the playful acrylics. Many of them are paper mounted on canvas. It’s only up close that you notice the lines: the stabs and scratches of an instrument used with force. ‘I’m not mad about the lyrical quality of the brush,’ she said in 2009. ‘I much prefer the hardness of the stick. The stick is fiercer, much much more aggressive.’

The Tate exhibition, curated by Elena Crippa, is framed in political terms. Rego is often described as depicting women’s lives (‘the best painter of women’s experiences alive today’, as Robert Hughes once called her) and just as often as ‘autobiographical’. To some extent the work invites this interpretation. She has described Nunes, the model for many of the later works, as her ‘stand-in’. The images of women crouching, contorted, lustful, angry, constrained by clothes, howling like wolves, caught up in strange or ambiguous games, deliberately confound our gaze. It’s not surprising that one response to these complex works is to treat them as part of a feminist project. An ardent paragraph of wall text at the Tate signs off by saying that ‘Rego is an artist who has consistently made work that responds to and fights injustice … Rego’s and our wish is that there might be an Escape, and more justice for all women.’

Perhaps this is not the moment to ask whether that interpretation limits her. The figures may be mostly female but the forces they channel are supernatural or unconscious, and their human forms are often cross-dressed. Rego’s best works look at politics askance – at power and repression, at the darkness between and within individuals. Growing up under a dictatorship, in a country whose oral tradition of song and stories was exuberantly sinister, gave her all the atmospheric politics she needed in order to conjure work that is unafraid to give a face to cruelty. If she is remembered for her fictions over her manifestos that will be no less important, and no less political, than the other way around.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.

%20_hi.jpg)