In 1909, at the age of nineteen, Nina Hamnett found herself paralysed. ‘I lost the use of my hands completely,’ she writes in her memoir, Laughing Torso (1932). The paralysis seems to have been brought on by her father, who disapproved of her ‘hopeless passion’ to be an artist. ‘If you continue this rot,’ he told her, ‘I will have you put in a lunatic asylum.’ Diagnosed with ‘spinal adhesion’ (an invented disease, she said), Hamnett was instructed to lie down for long periods, read light literature and avoid overtaxing her brain. Instead she read Kant, Schopenhauer and Baudelaire, and found a doctor who collaborated with a medium to treat patients using hypnosis. ‘What you want to do is some work, any kind, but occupy your mind,’ he told her. ‘From that moment,’ she recalled, ‘I recovered.’

Hamnett’s productivity waxed and waned throughout her life, but she never stopped rejecting the conventional – even if it meant enduring personal hardship. The phrase ‘Il vaut mieux le travail que la rêverie’ is said to have been pasted on the wall of the small, squalid room on Westbourne Terrace where she spent her final years. She died in 1956 but is only now receiving her first retrospective, at Charleston, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant’s house in Sussex (until 30 August). The drawings and paintings selected were created between 1908 and 1928, Hamnett’s most prolific years, and are on show alongside two large portraits of her by Roger Fry and a bronze sculpture by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, The Dancer (1913), for which she served as model.

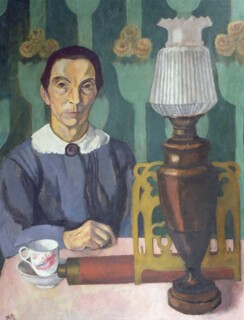

A trio of early still lifes are apparently influenced by William Nicholson, who taught Hamnett at the London School of Art, though her paintings have none of his opulence and clarity. Rather, they are tightly cropped compositions in which objects and forms are flattened and simplified. Planes shift and tilt in compressed geometries; colours are muted and grubby, flickering here and there with luminous accents. A painting from 1915 shows an angular white jug, a brown-striped teacup and what looks like a packet of butter arranged on a table. A stack of papers overlap at odd angles: a slender, russet-coloured book with a white label; a copy of Der Sturm, the avant-garde German magazine published between 1910 and 1932. The painting has an unusual sense of constrained vitality: it seems to incline towards us. Still Life (c.1913) is similarly striking, if more simple – so spare, in fact, that it verges on abstraction. A glass of wine stands on a stone-grey surface above rectangles of colour: salmon pink beneath dove grey, with a faint shadow at its edge. Apart from the translucent wine glass, its contents shining cornsilk yellow, the scene is flat, subdued.

These still lifes hint at Hamnett’s existence at the time: cramped rented rooms in Fitzrovia, days spent sketching at cafés and bars, nights on the town – the Domino Room at the Café Royal, the infamous Cave of the Golden Calf – with a growing circle of artist friends and lovers. They also show her influences, from Walter Sickert and Augustus John to Wyndham Lewis, Gaudier-Brzeska, Dora Carrington and Post-Impressionism. She supported herself by working a few days a week at Fry’s Omega Workshops: one of the young women – ‘cropheads’, Virginia Woolf called them, on account of their distinctive bobs – who painted decorative designs onto furniture, fabric, lampshades and other objects. ‘Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant worked sometimes at the Omega Workshops,’ Hamnett writes in Laughing Torso. ‘She was very beautiful and had a wonderful deep voice. I used to go home and attempt to lower my voice too. I think I succeeded to a certain extent after some practice.’ Bell’s impression of Hamnett was less favourable. In a letter to her husband, she describes a morning spent listening to Hamnett’s ‘appallingly sordid histories of her love affairs. She is known in Paris as a – could it be a “Lesbian”? Amorous Sapphist will do as well.’

It was in Paris, where Hamnett lived for much of 1914 (she returned many times in later years) that she hit her stride as a portraitist. In an article from 1924, she explained her preference for portraiture to the art critic Louise Gordon-Stables: ‘I am more interested in human beings than in landscapes or in still lifes. That is why I live in Paris and sit in cafés … My ambition is to paint psychological portraits that shall accurately represent the spirit of the age.’ The earliest portrait at Charleston, and one of Hamnett’s most striking, is a 1914 painting of the Russian artist Ossip Zadkine. He is shown in three-quarter profile at the centre of the image, a dramatic contrast of light and dark: brown bowl-cut hair and midnight blue sweater framing his pale face. His simplified form radiates composure. One of his sculptures – an oversized wooden bust – looms over his shoulder. Most beguiling are Hamnett’s carefully chosen shades of blue-black and purple, the way Zadkine’s dark torso becomes a void; the mauve shadows cast on the pale grey wall. Patches of rough canvas show through, at once part of the image and interruptions to its surface.

A sense of interiority and self-possession is common to all Hamnett’s portraits: they hold the viewer at a distance. Like her still lifes, they are anti-mimetic, creating the impression of a person rather than an exact likeness. Faces are smoothed and abstracted, with features almost sculptural in their clarity and bodies rendered in solid swathes of colour. James Hepburn (1922) and Rupert Doone (1922-23), in particular, are reminiscent of the stylised portraits of Modigliani (Hamnett was a close friend of his). Her bust-length paintings aren’t set in recognisable interiors but place their sitters against muted backgrounds of grey, blue, ochre, brown with a hint of green. In a preface to Hamnett’s show at the Eldar Gallery in 1918, Sickert – a mentor and supporter – wrote: ‘Like Hogarth, she picks her sitters, rather than suffers them gladly to pick her, so that in the end her gallery of portraits is likely to form an interesting sequence.’ Her work gathers together those who might be considered outsiders – queer, female, foreign, eccentric, artist, poet, libertine. Two portraits of landladies, from 1917 and 1918, show single women in comfortable interiors. One looks peacefully into the distance, a bowl of brightly coloured fruit to her right; the other confronts us with a direct and confident gaze. A telescope sits on the table in front of her: this is a woman of knowledge and education. The Student (1917) shows Dolores Courtney, with whom Hamnett studied at the London School of Art, holding a portfolio in her lap. Her surroundings and her dress, which is deliberately modern, create overlapping shapes of different colours, as if her youthful energy has seeped into the room. In Reclining Man (1918), the unidentified sitter lies on his side, head propped on hand, dark eyes looking out towards the viewer. His other hand clasps a glass of red wine. It’s a frank, intimate portrait that doesn’t exoticise its dark-skinned subject.

In Paris, Hamnett was a fixture of countercultural circles. The art was avant garde and the parties – usually at Café de la Rotonde or Le Dôme Café – were wild. Art critics held events at which people boxed in the corner. Hamnett was often out until 7 a.m.; revellers might stay up for three or four days at a time or finish the night by taking a train to Marseille, ending up in Corsica for weeks. People always seemed to be taking their clothes off. There was absinthe, whisky, wine, champagne, plums in kirsch, calvados, bol de cidre, hashish, cocaine, crème de menthe frappée and ‘Pernod Suze’, a drink invented by English expats who deemed French cocktails too weak. In London, too, ‘drink is a great problem,’ Hamnett writes in her second memoir, Is She a Lady? Fry and Sickert told her to slow down, work hard, not get too ‘distracted’ (i.e. drunk). But she thrived in these spaces, and her writing is full of the kinds of incident and encounter that would never have occurred in the other spheres available to her as a single woman.

In 1925, Fry ran into Hamnett at the Dôme. ‘Oh Lord! What a collapse,’ he wrote to his partner, Helen Anrep. ‘I suppose her endless petits verres and her endless coucheries have at last begun to tell, but she’s really repulsive.’ They had been lovers a few years earlier, and after it ended Fry told Bell that he had finally accepted Hamnett for who she was: ‘Elle est vraiment putain … a type of character comme un autre.’ Bell sent a sympathetic response: ‘I don’t think Nina (though I really like her) nearly good enough for you as a character or a mind.’ Fry’s comments bring to mind Marguerite’s Duras’s observation that ‘when a woman drinks it’s as if an animal were drinking, or a child. Alcoholism is a scandal in a woman and a female alcoholic is a rare, serious matter. It’s a slur on the divine in our nature.’ Hamnett’s memoirs are generous about almost everyone (she doesn’t even mention her affair with Fry), but she does subtly distance herself from the Bloomsbury Group. Of a 1926 review in the Westminster Gazette that referred to her as ‘this clever young Bloomsbury artist’, she says: ‘I am tired of explaining that I live in St Pancras.’ (One wonders what she would have made of being exhibited at Charleston.) Many of Hamnett’s friends in Paris were scornful of Bloomsbury, with its Fabian politics and bohemianism that involved no material risk. Her friends, such as Beatrice Hastings, the co-editor of the socialist magazine New Age, and the heiress Nancy Cunard (rumoured to be Hamnett’s lover), were active in the women’s suffrage and anti-imperialism movements. They did not, as Elizabeth Hardwick put it, ‘remain on the upper deck’.

The third and final room at Charleston is devoted to Hamnett’s drawings, many of them from the late 1910s. There are sketches from life-drawing classes, Paris café scenes and a rather vulnerable line-drawing of a naked, crouching Fry. The latest work in the show, and the most impressive of the drawings, is a portrait of Edith Sitwell from 1928, her elongated face and aquiline features captured in black chalk, outlined by delicate shadows along her temple, cheekbone, neck. Hamnett spent much of her final years drawing, often in pubs. Some despaired at her presence – she acquired the nickname ‘Dirty Nina’ – but she continued to meet artists, including Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon, who admired her and her work. Where are these later drawings now? Lost? Sold for a drink or some spare change? Many years before, she had given away drawings by Modigliani and Gaudier-Brzeska, handing them out to strangers at the bar. Her subjects and friends – dancers, painters, actresses, poets, models, many of them queer – are today largely unknown.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.