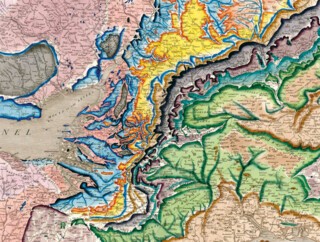

Behind velvet curtains on a staircase in the east wing of Burlington House in London is an eight foot tall map of England, Scotland and Wales made up of 15 pages (available to view by appointment). The survey, produced by William Smith and published in 1815, is considered the first true geological map. One doesn’t need to know anything about its subject to see at once that this is the work of a master craftsman, richly coloured and meticulously detailed. The copy on display at Burlington House is a later edition, possibly from 1836, and its colours have dulled a little, though a recent restoration has brought back some of its original vitality. A great deal of care was taken to make this an object of beauty as well as a cartographical tool. Lighter shading marks the places where each stratum is most proximate to the earth’s surface. Each colour fades as it rises: blue limestone in the Vale of Pickering gently diminishes, giving way to a dark green designating the chalk cliffs of the Yorkshire Wolds. The result is an intricate marbling, whose striations appear as many multicoloured shorelines woven into an undulating whole. A key floats in the North Sea (marked here as ‘The German Ocean’), east of the Humber, displaying a cross-section of strata. Smith’s Strata Identified by Organised Fossils (1816) introduced his principle of faunal succession, which posits that the fossil types present in each individual layer of rock beneath the Earth’s crust are unique – ‘peculiar to each stratum’ – and therefore if a fossil appears in abundance in two places, it is likely that these are parts of the same deposit. If such occurrences could be observed, Smith thought, they could also be mapped.

Smith drew his coloured strata directly onto a base map, made in 1794 by his publisher, the cartographer John Cary, before the fifteen sheets were engraved by assistants onto copper plates ready for reprinting – a process that took two years. He made several versions of the map during his lifetime, many of which he neither numbered nor named. Some of these iterations have been collated as part of a new book, Strata: William Smith’s Geological Maps (Thames and Hudson, £50), along with additional surveys and sketches and a series of essays that form a biography both of the man and of the emerging discipline. The publishers, with assistance from researchers at the Oxford Museum of Natural History, have created a coherent visual narrative, presenting a number of the maps that inspired Smith, as well as later works that drew on his techniques. In 1724, the geologist John Strachey (who had noticed the layered rock forms beneath the Somerset crust forty years before Smith was born) did a sketch in which coal veins are extrapolated across a ‘terraqueous globe’, starting at its core and swirling outwards. Strachey’s mistake, which Smith would initially repeat, was to imagine that the coal configurations beneath Somerset were copied ad infinitum across the world. He suggested that the curved structure of the strata was a result of the Earth’s rotation, as if each deposit was a layer of wet clay on a potter’s wheel. Strachey’s sketch looks like science fiction, but his strata – at least for Somerset – were accurately ordered and his ideas had a profound effect on Smith, who in a memorandum from 1798 referred to his and Strachey’s research as ‘our theory’.

Smith’s first-hand expertise distinguished his work from other early geological studies. His technical skills were honed over many years as a civil engineer and mineral surveyor. Growing up in rural Oxfordshire in the 1770s, Smith showed an early aptitude for mathematics and drawing. After his father died, he was sent, at the age of eight, to live with his uncle, who owned a nearby farm. He was fascinated by the stones used by his aunt (and all the local dairymaids) to measure out butter for market. The stones were chosen because they weighed a consistent 22 ounces and possessed a single flat surface, so would sit obligingly still on the scales. What the dairymaids referred to as a ‘pound-stone’ or a ‘Chedworth Bun’ was in fact a fossilised sea urchin, Clypeus ploti, and was more than 170 million years old.

At 18, Smith was hired as an assistant to the surveyor Edward Webb, and by the age of 25 he was working for the Somersetshire Coal Canal Company. It was while surveying Mearns Pit at High Littlejohn, one of the oldest coal mines in Britain, that he made his first observations about rock deposits. Smith wasn’t the first to notice that the layers in the pits were predictable in their order; miners had long used the rock formations as wayfinders. They had names for the various types of exposed coal they were extracting: between layers of sandstone, siltstone and mudstone there might be a vein of ‘Dungy Drift’ or ‘Temple Cloud’, each identifiable by its distinct fauna and flora, and each uncovered at a different depth. The ‘Slyving’ was always above the ‘Firestone’, for example. A miner could tell, simply by holding a torch to the sides of a pit, exactly where – and how deep – he was in the Somerset coalfields. Smith wondered whether ‘the superincumbent strata’ which rose ‘200 to 300 feet above the mouths of their coalpits’ followed the same rules. If these layers existed below the red sandstone (‘Red Marl’) into which the mines were drilled, then wouldn’t similar patterns be found in the surrounding hills? Would the coal veins be the lower layers of a much larger cake? The miners weren’t convinced. ‘I was told there was “nothing regular above the Red Ground”,’ Smith wrote in his diary. ‘This did not deter me from pursuing my own thoughts about the subject.’

For the next three decades, Smith travelled the country for the Canal Company and as a mineral surveyor for hire, recording the unique properties of the underworld wherever it was exposed to him. Strata includes a two-page spread entitled Geological Section from London to Snowdon, published in 1817, which shows Smith’s principle of faunal succession at work. Each wrinkle is coloured according to its identified stratum: a burnt auburn for granite, sienite and gneiss; blue for mountain limestone and a lighter pink for the beds of Red Marl. These eventually burst upwards through a thick lined crust into the mountain ranges of Berwyn and Snowdonia, which are expressionistic in style, despite Smith’s assertion that they display ‘the correct altitudes of the hills’. Reading his notes and diary entries, sections of which are published in Strata, it’s hard not to be struck by his love of the English countryside, even though his prose rarely extends beyond workmanlike observations. The title of his major book ran to 46 words: A Delineation of the Strata of England and Wales, with part of Scotland: exhibiting the collieries and mines, the marshes and fen lands originally overflowed by the sea, and the varieties of soil according to the variations in the substrata, illustrated by the most descriptive names. His ‘most descriptive’ passages on the topographies of the various strata are stodgy, but occasionally a hint of childish awe slips through. In some parts of Somerset and Devon, oaks ‘grow kindly’ on the ‘steep sides of woody glens’. Limestone and ‘flinty blue slate’ rise into ‘the most singular and romantic hills’. On Snowdon, he describes looking over ‘the sharp-pointed mountains which pierce the clouds’ and peering into ‘deep bottoms of spungy peat’. And, of course, ‘nothing can be more gloomy than the frowning brow of Dartmoor.’

Smith’s map was largely ignored when it was first published. He had supporters over the years (the naturalist and collector Joseph Banks donated £50 to the project) but his maps didn’t sell (the less than catchy titles can’t have helped) and were not at first used as mining tools, as Smith had envisaged they would be. He was forced to sell his superb fossil collection to the British Museum, but that only staved off the inevitable. By the late 1810s he was bankrupt. A second collection of maps was published the day after his release from the King’s Bench Debtors’ Prison in August 1819. He returned to his house at 15 Buckingham Street on the afternoon of his release to find bailiffs departing with his belongings. Smith promptly left London and refused to return for the next two decades. ‘London quitted with disgust, the cheering fields regained,’ he wrote years later. His self-imposed exile ended only when Sir John Johnstone – who employed him as a land steward on his estate in Hackness – brought Smith’s maps to the attention of the Royal Geographical Society.

A second map exists at Burlington House, behind another set of curtains. Produced by the first president of the Royal Geographic Society, George Greenough, it was published in 1820, five years after Smith’s, of which it is a near carbon copy. Nothing could be better evidence of the class prejudice that resulted in Smith’s endeavours going unrecognised for much of his life. In 1865, members of the society decided that all future reproductions of Greenough’s map should be printed with the caveat: ‘On the basis of the original map of Wm. Smith, 1815.’ Smith never became a member of the society, as he would have liked, but was awarded its first ever Wollaston Medal in 1831, eight years before his death.

In 2009, the Anthropocene Working Group was established by the International Commission on Stratigraphy to explore human impact on the future make-up of the Earth’s surface. Last year, its members voted (by 29 votes to five) to recognise the Anthropocene as a new geological time unit, beginning in the mid-20th century with the accelerated use of agricultural chemicals and the sharp increase in the production of inorganic waste. This start date also coincides with the first deployment of the atomic bomb, which covered the Earth with radioactive debris that is now embedded in glacial ice at both poles. In his foreword to Strata, Robert Macfarlane imagines a ‘far-future William Smith’ who is ‘prospecting the strata of the Anthropocene’ and discovers

the trace-fossils of billions of plastic bottles, chicken and swine bones in fabulous abundance, the crushed rubble of our cities, and a curious concentration of Lead-207, the stable isotope at the end of the Uranium-235 decay chain.

Smith’s coal miners weren’t wrong. In the post-Anthropocene world, there will be nothing regular above the Red Ground

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.