Horace was stridently anti-giraffe. The animal was, he believed, conceptually untidy: ‘If a painter had chosen to set a human head on a horse’s neck [or] if a lovely woman ended repulsively in the tail of a black fish, could you stifle laughter, friends?’ His account of the giraffe in Ars Poetica (c.8 bc) ends on a plea: ‘Let the work be what you like, but let it be one, single thing.’ When Julius Caesar brought a giraffe back to Rome from Alexandria in 46 bc (a gift, some said, from Cleopatra), the Romans, like Horace, saw a creature made of two parts. Cassius Dio wrote in his Historia Romana that it was ‘like a camel in all respects except that its legs are not all of the same length, the hind legs being the shorter … Towering high aloft, it … lifts its neck in turn to an unusual height. Its skin is spotted like a leopard.’ But the crowds, unlike Horace, rejoiced in the creature’s bravura hybridity. ‘And for this reason,’ Dio wrote, ‘it bears the joint name of both animals.’ Camelopardalis: camelopard.

Throughout history we have tried, with more enthusiasm than accuracy, to explain how something so mixed and miraculous came to be. The Persian geographer Ibn al-Faqih wrote in 1022 that the giraffe occurs when ‘the panther mates with the [camel mare]’. Zakariya al-Qazwini suggested in his Wonders of Creation (which also includes among its marvels al-mi’raj, a rabbit with the horn of a unicorn) that its genesis was the result of a two-part concatenation: ‘The male hyena mates with the female Abyssinian camel; if the young one is a male and covers the wild cow, it will produce a giraffe.’ Both possibilities sound more stressful than would be ideal from an evolutionary point of view. Others have declared it magical: the early Ming dynasty explorer Zheng He brought two giraffes to Nanjing and hailed them as qilin, a gentle hooved chimera. Charles I’s chaplain, Alexander Ross, wrote in Arcana Microcosmi in 1651 that the sheer fact of the giraffe made it impossible for naturalists to ‘overthrow the received opinion of the ancients concerning griffins … seeing there is a possibility in nature for such a compounded animal. For the gyraffa, or camelopardalis, is of a stranger composition, being made of the leopard, buffe, hart and camel.’

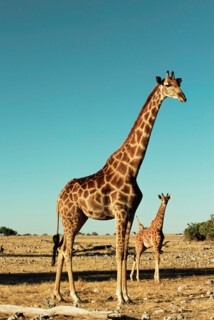

Ross was right: the truths of the giraffe are more fabulous and potent than our fictions. Giraffes are born with no aid from the camel or hyena, but even so their birth is a wonder: they gestate for 15 months, then drop into existence a distance of five feet from the womb to the earth. It looks as brisk and simple as emptying out a handbag. Within minutes, they can stand on their trembling, catwalk-model legs and suckle at their mother’s four teats, biting off the little wax caps that have formed in the preceding days to keep the milk from leaking out. Soon they are ready to run, but still liable to trip over their own hind legs, a hazard they never learn entirely to avoid.

Once full grown they can gallop at 40 mph on feet the size of dinner plates, but it remains safer not to: they self-entangle. Their tongue, which is dark purplish-blue to protect it from the sun and more powerful than that of any other ungulate, is fifty centimetres long: they can scrape the mucus from deep inside their own nostrils with the tip. And they are the skyscrapers of mammals, unmatched: the tallest giraffe ever recorded, a Masai bull, measured 19.3 feet. The explorer John Mandeville only mildly exaggerated when he wrote of the ‘gerfauntz’, in the first English-language account in 1356, that it had a neck ‘twenty cubytes long [about thirty feet] … he may loken over a gret high hous.’ (As Mandeville is himself a fictional appellation for an unknown man, some laxity in measurements is to be expected.) But though so tall, they are hospitable to the small. They have been known to host tiny yellow-billed oxpeckers on their bodies: the small birds remove ticks from their skin, and clean the food from between their teeth. Giraffes have been photographed at night with clusters of sleeping birds tucked into their armpits, keeping them dry.

We don’t know why the giraffe looks as it does. Until relatively recently, its neck was explained in the way Darwin suggested: the ‘competing browsers hypothesis’ posits, commonsensically, that competition from browsers such as impala and kudu encouraged the gradual lengthening of the neck, allowing it to reach food the others couldn’t. Recently, though, it has been shown that giraffes spend relatively little time browsing at full height, and the longer-necked individuals are more likely to die in times of famine. It is possible that it gives males an advantage when they engage in ‘necking’ – swinging their necks against one another, seemingly to establish dominance. (There will surely be more to discover about necking, too, in years to come: it often leads to sexual activity between the warring males. Indeed, most sex between giraffes is homosexual: in one study, same-sex male mounting counted for 94 per cent of all sexual behaviour observed.) Whatever its reason, the neck comes at a price. Each time a giraffe dips down to drink, legs splayed, the blood rushes to its brain; as it bends, the jugular vein closes off blood to the head, to stop it fainting when it straightens up again. Even when water is plentiful, they drink only every few days. It is a dizzying thing, being a giraffe.

In Atlanta, Georgia it is illegal to tie your giraffe to a streetlamp. It is not illegal, though, to import a cushion made from a freshly shot giraffe’s head with the eyelashes still attached. The United States is one of the largest markets in the world for giraffe parts, in part because America has refused to designate the animals endangered, despite the fact that there are fewer than 68,000 left in the wild, a 40 per cent drop in thirty years. In a ten-year period, American hunters imported 3744 dead giraffes – about 5 per cent of the total number alive. Today you could, if you felt like externalising the apocalyptic whiff of your personality, buy both a floor-length giraffe coat and a Bible in a giraffe skin cover. Rarer breeds are on the very edge of vanishing: the population of Nubian giraffe has fallen by 98 per cent in the last four decades, and they will soon be extinct in the wild. Their own beauty imperils them. As Pliny says, the proof of wealth is ‘to possess something that might be absolutely destroyed in a moment’.

There is something in giraffes that unhinges us in our delight. In 1827, a giraffe walked into Paris. She was not the first giraffe in Europe – Lorenzo de’ Medici had brought a giraffe through Italy in 1487, Florentines leaning perilously out of second-floor windows to feed it – but she was the best dressed. Wearing a two-piece custom-made raincoat embroidered with fleurs-de-lis, she was a gift from the Egyptian ruler Muhammad Ali to Charles X. She travelled for more than two years from Sennar by camel, boat and on foot, arriving in Paris in high summer; there she bent to eat rose petals from the king’s hand. She was known as ‘la Belle Africaine’, ‘le bel animal du roi’ and, most often, ‘la girafe’: like God and the king, there was only one. She was housed in the royal menagerie in an enclosure with a polished parquet floor (‘truly the boudoir of a little lady’, the keeper wrote) and Parisians, filing past to see her in their thousands, went giraffe-crazy. Shops filled with giraffe porcelain, soap, wallpaper, cravats, giraffe-print dresses; the colours of the year were ‘Giraffe belly’, ‘Giraffe in love’ and ‘Giraffe in exile’. Hair was worn vertically in Paris that season. Women smeared their hair with hogs’ lard pomade fragranced with orange flower and jasmine, and wound it to resemble the giraffe’s ossicones. There were reports of women sitting on the floors of their carriages, so high did their coiffures à la girafe rise.

But we tire of everything, even miracles. Charles X abdicated, his son ruled for twenty minutes, and la girafe outlived her fame. She died unvisited in 1845, was taxidermied and put in the foyer of the Jardin des Plantes. Delacroix, under the false impression that she was male, went to see the body: the giraffe, he wrote, died ‘in obscurity as complete as his entry in the world had been brilliant’. But the wild Parisian reaction, it seems to me, was the only reasonable one. It should never have died down: we should still be wearing our hair in 12-inch towers. Why did we ever stop? The world is a wild and unlikely place: the giraffe, stranger than the griffin, taller than a tall house, does us the incomparable gift of being proof of it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.